Terrible Swift Sword (33 page)

Read Terrible Swift Sword Online

Authors: Joseph Wheelan

MARCH 2, 1865âWAYNESBORO, VIRGINIAâPouring rain cloaked Sheridan's men and horses in a special kind of misery as they rode east from Staunton toward Waynesboro, ten miles away. “The by-roads were miry beyond description, rain having fallen incessantly since we left Winchester,” Sheridan wrote, “men and horses growing almost unrecognizable from the mud covering them from head to foot.”

16

16

With Torbert disabled by a flare-up of a spinal abscess, Merritt was in command of the 9,000-man Cavalry Corps when it rode out of Winchester, four abreast, for the last time on February 27. Sheridan had elected not even to attempt to recall Torbert, who “had disappointed me” after Fisher's Hill and during his failed raid on Gordonsville in December. When he did return to duty, Torbert would command the remnants of the Army of the Shenandoah scattered across the lower Valley. His war was over.

“It was a grand sight,” a witness wrote of the cavalry's departure from Winchester. The horse's equipage, she said, “shone like gold.” The long column of mounted troops quickly lost its spit and polish, however, in the rain and mud.

17

17

Â

TWO AVOWEDLY DISAFFECTED REBELS who had offered Sheridan their services had turned out to be Confederate spies, which Sheridan had discovered after sending them on phony missions and having Young's scouts follow them. Surprisingly adroit at counterintelligence work, Sheridan had kept the spies in play, feeding them false information to take back to the Confederates. Near Staunton, he supplied them with one last fiction: that he planned to hold a fox hunt. His purpose was to lull the Rebels into thinking that his army planned to remain in Staunton.

After Young's scouts watched the spies pass on the information to the Rebels, they arrested the men. The pair later escaped from their guards in Baltimore while en route to the Union prison at Fort Warren; they were never seen again. In his

Personal Memoirs

, Sheridan speculated that the men might have been involved in the conspiracy to assassinate President Abraham Lincoln.

18

Personal Memoirs

, Sheridan speculated that the men might have been involved in the conspiracy to assassinate President Abraham Lincoln.

18

Of course, there was no fox hunt, and Early was not fooled anyway. He collected Wharton's skeletal division of 1,500 infantrymen, Rosser's 500 troopers, and some artillery, and they marched to Waynesboro to await Sheridan. Early made a point of telling people in Staunton that he intended to fight Sheridan there.

19

19

Â

THE 4,500 MEN OF Custer's division led the way to Waynesboro, proudly displaying their red ties, formerly the signature attire of his Wolverine Brigade.

The responsibilities of the twenty-five-year-old “boy general” had grown during his seven months in Sheridan's Shenandoah army, and he had become one of Sheridan's most dependable combat leaders. He had tipped the scales at Winchester, Cedar Creek, and Tom's Brook. Just days earlier, during the march up the Valley to Staunton, he had boldly swum two regiments over the North Fork of the Shenandoah River to flank his old friend Rosser when Rosser had tried to bar Custer's crossing.

On this miserable day, Custer would display to stunning effect the battle skills that he had mastered in the Valley.

Â

EARLY HAD PLACED HIS small force and cannons on a commanding ridge northwest of Waynesboro. Nestled in a bend of the South River, the high ground overlooked the town and the Staunton Pike. But Custer instantly perceived the Confederate position's major vulnerability: Early's left flank was anchored not on the river but on a patch of woodsâwoods that might be infiltrated to turn his flank.

Custer implemented a simple tactical plan. While he kept Early occupied on his main front, three regiments slipped into the woods on Early's left. When gunfire erupting in the woods signaled that the regiments had made contact with the Rebels, the rest of the division attacked frontally.

The shattering twin assaults sent the Rebels into panicked flightâwhich took them into the clutches of Union cavalrymen who had cut off the Confederates' retreat. “I now saw that everything was lost. . . . . I rode aside into the woods, and in that way escaped capture,” wrote Early, who got away with his staff, Wharton, and fifteen or twenty others. Custer captured 1,600 of Early's 2,000 men, along with eleven guns, seventeen battle flags, ambulances and wagons, and Early's headquarters wagon with all of his army's records.

Early's Army of the Valley no longer existed, and the road to Charlottesville lay wide open to Sheridan's cavalry.

20

20

Â

THE NEXT DAY, A delegation of Charlottesville leaders awaited Custer on the town's outskirts. “With medieval ceremony,” they handed over the keys to all the public buildings and the University of Virginia. When Custer learned that townspeople feared the Yankees might destroy the historic campus designed by Thomas Jefferson, he ringed it with a provost guard to keep everyone away.

21

21

Â

WHILE HIS CAVALRY WRECKED the James River canal and tore up the Virginia Central Railroad, Sheridan sought a place to cross the James. He had concluded that Lynchburg was too heavily defended and instead had decided to cross the river, march on Appomattox Court House, and destroy the Southside Railroad, the Rebels' crucial lifeline to Petersburg and Richmond. But the Confederates had burned the bridges, and the James River was too swollen by the heavy rains to ford. Moreover, the army did not have enough pontoon bridges for a river crossing. Sheridan could not reach Appomattox Court House.

Sheridan had a clear path eastward along the James's north bank, though. Neither enemy troops nor natural barriers would stand in the way of his army riding eastward, skirting Richmond's northern and eastern approaches, and joining Grant outside Petersburg. “I was master of the whole country north of the James as far down as Goochland, hence the destruction of these arteries of supply could be easily

compassed, and feeling that the war was nearing its end, I desired my cavalry to be in at the death,” he wrote.

compassed, and feeling that the war was nearing its end, I desired my cavalry to be in at the death,” he wrote.

On March 9, the army rode east, destroying locks, dams, and boats on the James River and wrecking tracks and rails on the Virginia Central Railroad. Sheridan sent a message to Grant requesting that rations and forage be sent to White House, along with a pontoon bridge so that he could cross the Pamunkey River there.

22

22

At Frederick's Hall Station, Custer captured the telegraph office and found an unsent message from Early to Lee revealing that Early planned to attack Sheridan with two hundred cavalrymen. Two hours later, Custer's cavalrymen scattered Early's ambush party, capturing most of them. Early and a half dozen Confederatesâthe last remnant of the army that had threatened Washington the previous Julyâescaped to Richmond.

Early was ill, and he went home to Lynchburg, where a letter waiting for him from Lee informed him that he was relieved of his command. “Your reverses . . . . have, I fear, impaired your influence both with the people and the soldiers,” Lee wrote, but he added that he still believed in his downtrodden general.

23

23

Â

IT RAINED DAY AND night as Sheridan's cavalrymen rode east. The roads were “wellnigh bottomless,” horses staggered from fatigue, and troopers nodded off in the saddle. “But all hearts were jubilant,” wrote Captain Harlan Lloyd, “and soldiers were never known in better spirits than we were.” “Every one was buoyed up by the cheering thought that we should soon take part in the final struggle of the war,” Sheridan wrote.

24

24

At White House on March 19, Sheridan wired a request for twenty-five forges to make replacements for his horses' shoes, worn out by the nearly two-hundred-mile march over rough roads and through mud. Farriers reported 2,000 cases of “hoof rot.”

A week later, the cavalry crossed the James River on a bridge below Dutch Gap Canal, as President Lincoln, Grant, and Sheridan watched from the steamer

Mary Martin

; Lincoln was paying an extended visit to Grant's City Point headquarters. Sheridan's men once more made their camp on the James's south bank.

25

Mary Martin

; Lincoln was paying an extended visit to Grant's City Point headquarters. Sheridan's men once more made their camp on the James's south bank.

25

Â

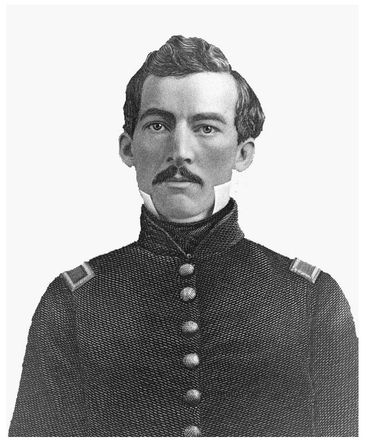

One of the earliest known photographs of Philip Sheridan, depicted here as a second lieutenant fresh from the U.S. Military Academy.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Â

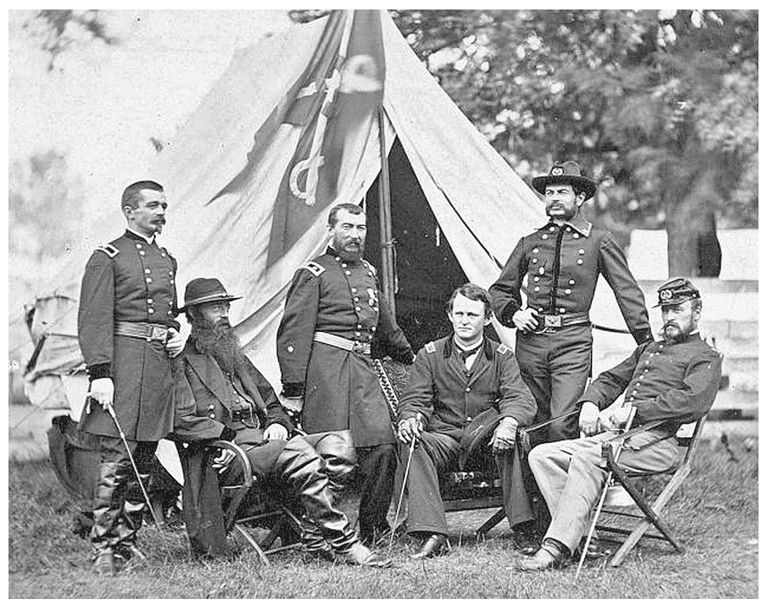

Sheridan with some of his Civil War cavalry commanders, from left: James Forsyth, Sheridan's chief of staff; David Gregg; Sheridan; Wesley Merritt; Alfred Torbert; and James Wilson.

Library of Congress

Library of Congress

Â

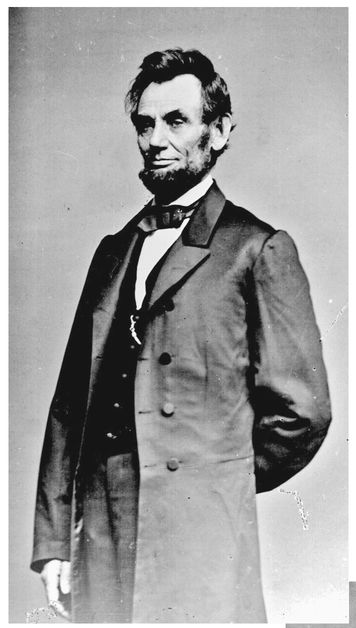

President Abraham Lincoln

National Archives

National Archives

Â

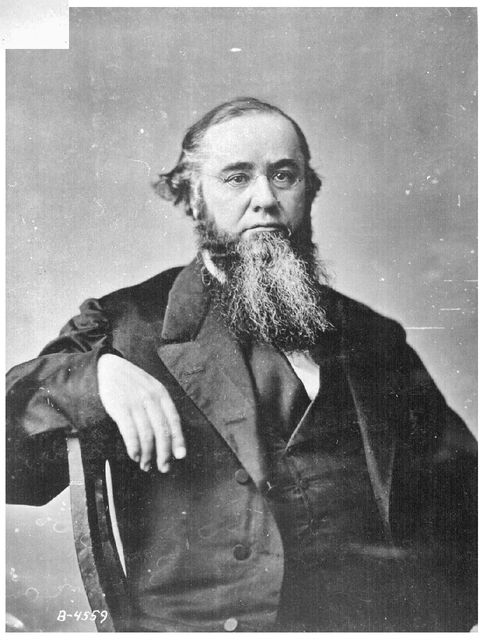

War Secretary Edwin Stanton

National Archives

National Archives

Â

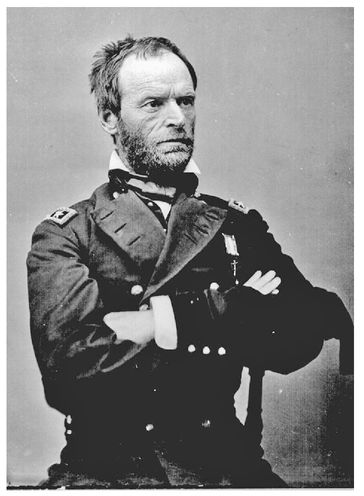

Major General William T. Sherman

National Archives

National Archives

Â

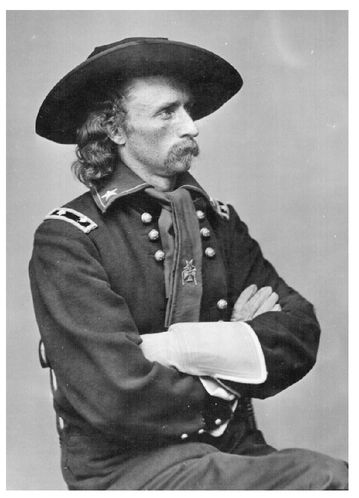

George Armstrong Custer

National Archives

National Archives

Other books

Playing With Fire (Guarded Hearts) by Noelle, Alexis

Savannah Sacrifice by Danica Winters

Ash Mistry and the Savage Fortress by Sarwat Chadda

Furnace by Joseph Williams

The Light of His Sword by Alaina Stanford

Jonathan Moeller - The Ghosts 07 - Ghost in the Ashes by Jonathan Moeller

A MATTER OF TRUST by Kimberley Reeves

Bill James Guide to Baseball Managers, The by James, Bill

Close Your Eyes by Robotham, Michael

9781631053566SpringsDelightBallNC by Kathleen Ball