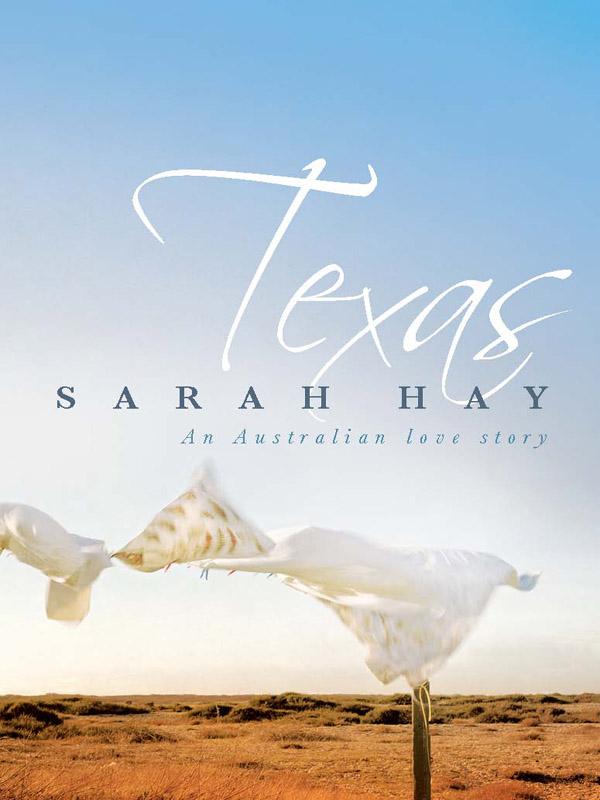

Texas

Praise for

Skins

â

Skins

is a deserving winner of

The Australian

/Vogel Literary Award for 2001 . . . Hay has created strong characters who have depth and lessons for the 21st century. A young writer to watch.'

The Press

, Christchurch

âIn 1802, Flinders's landscape artist William Westall drew a romantic pencil sketch of an uninhabited middle island that makes it look Arcadian. Hay's achievement lies in populating the same place with characters, based on history, who transformed a panorama of paradise into hell on earth.'

The Weekend Australian

âThe great strength of Hay's writing is its visceral quality: the detail with which she describes Dorothea kneading dough on roughly cured kangaroo skin; the misery of the cold kept at bay only by fire and insect-ridden skins; and the blood-splattered brutality of hunting expeditions for baby seal skins. If the drama and palpability of these scenes can at times seem overwhelming, their power is to immerse the reader in the rawness of Dorothea's experience.'

Australian Book Review

âSet in a world of desperation, squalor and violence,

Skins

combines a delicate feel for human character differences in contrast with the raw strength needed for survival in a brutal and sometimes brutish community.'

Katherine Cummings,

Sydney Morning Herald

âHay is a tactile writer . . .

Skins

is a novel which operates by stealth, building its effects gradually, in layers.'

Danielle Wood,

The Sunday Tasmanian

â

Skins

is set on the islands off the West Australian coast, and draws upon historical fact to transform these islands into a theatre for the darker impulses of human nature . . . Hay reveals, gradually and with considerable acuity, the complexities embodied in any choice, and the delicate interplay of need that exists between the weak and the strong.'

James Bradley,

Good Reading

â

Skins

is an excellent first novel, tightly and evenly constructed, with an accessible, unobtrusive and unforced style . . . These themes make for compelling reading and the characters are so well constructed that the reader can't help but be curious about their fate, even the most unlikable ones.'

Australian Bookseller and Publisher

â

Skins

is a fascinating journey into Australian history.'

Melbourne Weekly Magazine

âHay has a striking ability to present anomalies in a way that illuminates them for readers to contemplate . . . the rhythm of her writing creates a tone that compliments the story. Hay has a gift for mirroring language to the events it conveys.'

Antipodes

Sarah Hay's first novel,

Skins

, won

The Australian

/Vogel Literary Award in 2001. Sarah grew up in Esperance, Western Australia, and has worked in journalism and public relations. She now lives in Perth and is studying at the University of Western Australia.

Texas

SARAH HAY

An Australian love story

The State of Western Australia has made an investment in this project through the Department of Culture and the Arts.

An earlier version of an extract of this work was previously published in

Westerly

, vol. 50, November 2005, pp. 236â9.

First published in 2008

Copyright © Sarah Hay 2008

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher. The

Australian Copyright Act 1968

(the Act) allows a maximum of one chapter or 10 per cent of this book, whichever is the greater, to be photocopied by any educational institution for its educational purposes provided that the educational institution (or body that administers it) has given a remuneration notice to Copyright Agency Limited (CAL) under the Act.

Allen & Unwin

83 Alexander Street

Crows Nest NSW 2065

Australia

Phone: (61 2) 8425 0100

Fax: (61 2) 9906 2218

Email: [email protected]

Web:

www.allenandunwin.com

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication entry:

Hay, Sarah, 1966-

Texas

ISBN 978 1 74175 394 3 (pbk.)

A823.4

Internal design by Lisa White

Set in 11/16 pt Minion Pro by Bookhouse, Sydney

Printed in Australia by McPherson's Printing Group

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Jamie and Robert

Contents

All for a strip of rocky ground

Determined to stand tall on the untamed frontier

Men fell prey to her angel eyes and her killing ways

For the heir to triumph the father must fall

With a gun in his fist he was ten feet tall

All for a strip of

rocky ground

I

Susannah could see that something was not quite right on the road ahead. The way the lights were tilted seemed wrong. To begin with they were tiny, winking in the far flat expanse of the night, beyond the thin band of bitumen road that was lit up by their own vehicle's headlights. And it was impossible to tell whether the lights were on the earth or above it. She glanced at her husband's profile. It appeared in the greenish glow of the dashboard as an outline and not a real face, but the angle suggested determination and fearlessness.

âCan you see that?'

âYeah.'

âWhat do you think it is?'

His eyes didn't leave the screen. âMaybe a smash.'

She stared hard through the dark, and the lights disappeared.

But before they did she saw that there were two of them, one on top of the other, and they were on her husband's side of the road. A set of reflector posts flashed past. And then they reached it, captured by the high beam of their vehicle: a truck lying sideways and cattle on the road. It had come from the opposite direction. Her husband stepped hard on the brake and she was thrust into her seatbelt, seeing through the windscreen the bull bar touching the rump of a bullock. She put her hand out as though to prevent her children from falling, but they were strapped to their seats. He slowly eased the vehicle onto the gravel, the headlights finding the stunned eyes of cattle, several on the edge of the bush. They must have escaped from the truck. The one they hit was seemingly unhurt, its flank disappearing into the darkness. John turned off the vehicle's engine.

âBarely touched it,' he said.

He opened the door.

âWhat are you doing?'

âI'm going to have a look.'

âMummy, I'm thirsty.'

âShush. Be careful.'

He stepped out, slamming the door too hard so that the impact of metal on metal jarred, and crossed the road, the darkness folding him away. She hoped no one was injured.

A child moaned irritably. There was a short hard sound and at first it didn't register. But when it sounded again, she knew that noise: it was a gun being fired, like when the roo shooters were out at night on the boundary of her parents' farm. She sat forward in her seat, feeling her skin shrink.

âMummy.'

She wanted to be sick and her stomach hurt. There was a figure in front of the overturned cattle truck.

âBe quiet, be quiet,' she said urgently.

Her husband opened the door and climbed in. He stared straight ahead and turned the key in the ignition.

âWhat is it?'

He drove slowly back onto the road.

âSome cattle were injured. In the truck,' he added.

âSo who was it, were they all right?'

âSome things you're better off not knowing about.'

âWere they thieves?'

But her husband concentrated on the road in front of him and she wondered what he was thinking.

About two hours later their headlights picked out the white painted posts of a fence. A generator throbbed through the night air and a dog barked. The dark and its density engulfed her. The car engine clicked as the metal cooled. He gripped the wheel and turned towards her. She looked over her shoulder to avoid the hesitation in his eyes. The children's limbs were loose with sleep, fat and smooth, revealed by the triangle of light that shone from the roof. One of them seemed to sense the change in motion and stirred a little, muttering. He opened the car door and she watched him disappear around the side of the house. She climbed out, almost falling. Barefoot in the soft warm dirt, she stretched and the blood flowed to the rest of her body; silent, conscious of her breathing, in and out, feeling crowded by what lay beyond the artificial light.

John returned with a shorter, square-shaped man who wore a shirt with sleeves ripped from the shoulders. His forearms were thickly veined. He told them they weren't expected until next week. John walked behind their vehicle and began unloading the bags and the other man stepped forward to help him. Ned started to cry, waking his brother. She reached into the car to get the boys out of their seats, lifting them, one at a time, and placing them on the ground beside her, holding their hands in the darkness. They were irritable from being woken again. The men gathered their odd assortment of suitcases and bags and headed towards the veranda. She followed, coaxing the children to walk with her. They reached a doorway and the man turned on a switch and held open the flywire door. The twin fluorescent tubes flickered and hesitated before they became a strong white light. Something scuttled out of sight and the door scraped the concrete floor as it closed behind them. They were in the kitchen. It smelt of old blood and burnt animal fat. The surfaces looked greasy and were dotted with dead insects. A thickset timber table, its top covered with faded green, red and yellow linoleum, was in the centre of the room.

Mismatched chairs surrounded it. A small gas oven and cook top stood dwarfed in the recess where once there would have been a wood-fired stove. The render behind it was splattered brown. Obviously no one had ever bothered to clean it. She turned to the small man who remained in the doorway.

âAre there any women here?' she asked.

Texas He shook his head. âNo, only blokes. Camped out at number eight bore.'

Her husband avoided her eye. She let go of the boys, and the men returned to the car to finish unpacking. She heard them talking on the veranda.

âThey would've been cattle duffers, maybe contractors, you know, with their own truck,' the other man said.

She sat with the children at the table, tracing the patterns on the lino. Clouds of green overlaid by dashes of red and yellow stripes. She told them a story. The stripes became birds in a tree talking to each other about how they had flown a long way north and how they would need to build a new nest. They were like the green and black parrots from home, she said, but the boys couldn't remember them.