The 12th Planet (29 page)

Authors: Zecharia Sitchin

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Gnostic Dementia, #Fringe Science, #Retail, #Archaeology, #Ancient Aliens, #History

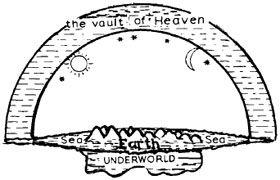

Fig. 88

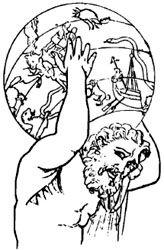

Fig. 89

Our textbooks generally credit Nicolaus Copernicus with the discovery that Earth is only one of several planets in a heliocentric (Sun-centered) system. Fearing the wrath of the Christian church for challenging Earth's central position, Copernicus published his study

(De revolutionibus orbium coelestium)

only when on his deathbed, in 1543.

Spurred to reexamine centuries-old astronomical concepts primarily by the navigational needs of the Age of Discovery, and by the findings by Columbus (1492), Magellan (1520), and others that Earth was not flat but spherical, Copernicus depended on mathematical calculations and searched for the answers in ancient writings. One of the few churchmen who supported Copernicus, Cardinal Schonberg, wrote to him in 1536: "I have learned that you know not only the groundwork of the ancient mathematical doctrines, but that you have created a new theory . . . according to which the Earth is in motion and it is the Sun which occupies the fundamental and therefore the cardinal position."

The concepts then held were based on Greek and Roman traditions that Earth, which was flat, was "vaulted over" by the distant heavens, in which the stars were fixed. Against the star-studded heavens the planets (from the Greek word for "wanderer") moved around Earth. There were thus seven celestial bodies, from which the seven days of the week and their names originated: the Sun (Sunday), Moon (Monday), Mars

(mardi),

Mercury

(mercredi),

Jupiter

(jeudi),

Venus

(vendredi),

Saturn (Saturday). (Fig. 90)

These astronomical notions stemmed from the works and codifications of Ptolemy, an astronomer in the city of Alexandria, Egypt, in the second century

A.D.

His definite findings were that the Sun, Moon, and five planets moved in circles around Earth. Ptolemaic astronomy predominated for more than 1,300 years—until Copernicus put the Sun in the center.

While some have called Copernicus the "Father of Modern Astronomy," others view him more as a researcher and reconstructor of earlier ideas. The fact is that he pored over the writings of Greek astronomers who preceded Ptolemy, such as Hipparchus and Aristarchus of Samos. The latter suggested in the third century

B.C.

that the motions of the heavenly bodies could better be explained if the Sun—and not Earth—were assumed to be in the center. In fact, 2,000 years before Copernicus, Greek astronomers listed the planets in their correct order from the Sun, acknowledging thereby that the Sun, not Earth, was the solar system's focal point.

Fig. 90

The heliocentric concept was only rediscovered by Copernicus; and the interesting fact is that astronomers knew more in 500

B.C.

than in

A.D.

500 and 1500.

Indeed, scholars are now hard put to explain why first the later Greeks and then the Romans assumed that Earth was flat, rising above a layer of murky waters below which there lay Hades or "Hell," when some of the evidence left by Greek astronomers from earlier times indicates that they knew otherwise.

Hipparchus, who lived in Asia Minor in the second century

B.C.

, discussed "the displacement of the sostitial and equinoctial sign," the phenomenon now called precession of the equinoxes. But the phenomenon can be explained only in terms of a "spherical astronomy," whereby Earth is surrounded by the other celestial bodies as a sphere within a spherical universe.

Did Hipparchus, then, know that Earth was a globe, and did he make his calculations in terms of a spherical astronomy? Equally important is yet another question. The phenomenon of the precession could be observed by relating the arrival of spring to the Sun's position (as seen from Earth) in a given zodiacal constellation. But the shift from one zodiacal house to another requires 2,160 years. Hipparchus certainly could not have lived long enough to make that astronomical observation. Where, then, did he obtain his information?

Eudoxus of Cnidus, another Greek mathematician and astronomer who lived in Asia Minor two centuries before Hipparchus, designed a celestial sphere, a copy of which was set up in Rome as a statue of Atlas supporting the world. The designs on the sphere represent the zodiacal constellations. But if Eudoxus conceived the heavens as a sphere, where in relation to the heavens was Earth? Did he think that the celestial globe rested on a

fiat

Earth—a most awkward arrangement—or did he know of a spherical Earth, enveloped by a celestial sphere? (Fig. 91)

Fig. 91

The works of Eudoxus, lost in their originals, have come down to us thanks to the poems of Aratus, who in the third century

B.C.

"translated" the facts put forth by the astronomer into poetic language. In this poem (which must have been familiar to St. Paul, who quoted from it) the constellations are described in great detail, "drawn all around"; and their grouping and naming is ascribed to a very remote prior age. "Some men of yore a nomenclature thought of and devised, and appropriate forms found."

Who were the "men of yore" to whom Eudoxus attributed the designation of the constellations? Based on certain clues in the poem, modern astronomers believe that the Greek verses describe the heavens as they were observed in

Mesopotamia

circa 2200

B.C.

The fact that both Hipparchus and Eudoxus lived in Asia Minor raises the probability that they drew their knowledge from Hittite sources. Perhaps they even visited the Hittite capital and viewed the divine procession carved on the rocks there; for among the marching gods two bull-men hold up a globe—a sight that might well have inspired Eudoxus to sculpt Atlas and the celestial sphere. (Fig. 92)

Fig. 92

Were the earlier Greek astronomers, living in Asia Minor, better informed than their successors because they could draw on Mesopotamian sources?

Hipparchus, in fact, confirmed in his writings that his studies were based on knowledge accumulated and verified over many millennia. He named as his mentors "Babylonian astronomers of Erech, Borsippa, and Babylon." Geminus of Rhodes named the "Chaldeans" (the ancient Babylonians) as the discoverers of the exact motions of the Moon. The historian Diodorus Siculus, writing in the first century

B.C.

, confirmed the exactness of Mesopotamian astronomy; he stated that "the Chaldeans named the planets ... in the center of their system was the Sun, the greatest light, of which the planets were 'offspring,' reflecting the Sun's position and shine."

The acknowledged source of Greek astronomical knowledge was, then, Chaldea; invariably, those earlier Chaldeans possessed greater and more accurate knowledge than the peoples that followed them. For generations, throughout the ancient world, the name "Chaldean" was synonymous with "stargazers," astronomers.

Abraham, who came out of "Ur of the Chaldeans," was told by God to gaze at the stars when the future Hebrew generations were discussed. Indeed, the Old Testament was replete with astronomical information. Joseph compared himself and his brothers to twelve celestial bodies, and the patriarch Jacob blessed his twelve descendants by associating them with the twelve constellations of the zodiac. The Psalms and the Book of Job refer repeatedly to celestial phenomena, the zodiacal constellations, and other star groups (such as the Pleiades). Knowledge of the zodiac, the scientific division of the heavens, and other astronomical information was thus prevalent in the ancient Near East well before the days of ancient Greece.

The scope of Mesopotamian astronomy on which the early Greek astronomers drew must have been vast, for even what archaeologists have found amounts to an avalanche of texts, inscriptions, seal impressions, reliefs, drawings, lists of celestial bodies, omens, calendars, tables of rising and setting times of the Sun and the planets, forecasts of eclipses.

Many such later texts were, to be sure, more astrological than astronomical in nature. The heavens and the movements of the heavenly bodies appeared to be a prime preoccupation of mighty kings, temple priests, and the people of the land in general; the purpose of the stargazing seemed to be to find in the heavens an answer to the course of affairs on Earth: war, peace, abundance, famine.

Compiling and analyzing hundreds of texts from the first millennium

B.C.

, R. C. Thompson

(The Reports of the Magicians and Astrologers of Nineveh and Babylon)

was able to show that these stargazers were concerned with the fortunes of the land, its people, and its ruler from a national point of view, and not with individual fortunes (as present-day "horoscopic" astrology is):

When the Moon in its calculated time is not seen, there will be an invasion of a mighty city.

When a comet reaches the path of the Sun, field-flow will be diminished; an uproar will happen twice.

When Jupiter goes with Venus, the prayers of the land will reach the heart of the gods.

If the Sun stands in the station of the Moon, the king of the land will be secure on the throne.

Even this astrology required comprehensive and accurate astronomical knowledge, without which no omens were possible. The Mesopotamians, possessing such knowledge, distinguished between the "fixed" stars and the planets that "wandered about" and knew that the Sun and the Moon were neither fixed stars nor ordinary planets. They were familiar with comets, meteors, and other celestial phenomena, and could calculate the relationships between the movements of the Sun, Moon, and Earth, and predict eclipses. They followed the motions of the celestial bodies and related them to Earth's orbit and rotation through the heliacal system—the system still in use today, which measures the rising and setting of stars and planets in Earth's skies relative to the Sun.