The Act of Creation (45 page)

Read The Act of Creation Online

Authors: Arthur Koestler

familiar, of the rustling of leaves in the dark forest to the whisper of

fairies or the vibrations of compressed air -- both equally reassuring

-- is merely the negative aspect of the power of explanation: relief

from anxiety. Its positive aspect is epitomized in the Pythagorean

belief that musical harmonies govern the motion of the stars. The myth

of creation appeals not only to man's abhorrence of chaos, but also to

his sense of wonder at the cosmic order: light is more than the absence

of darkness, and law more than the absence of disorder. I have spoken

repeatedly of that sense of 'oceanic wonder' -- the most sublimated

expression of the self-transcending emotions -- which is at the root of

the scientist's quest for ultimate causes, and the artist's quest for the

ultimate realities of experience. The sensation of 'marvellous clarity'

which enraptured Kepler when he discovered his second law is shared by

every artist when a strophe suddenly falls into what seems to be its

predestined pattern, or when the felicitous image unfolds in the mind --

the only one which can 'explain' by symbols the rationally unexplainable

-- and express the inexpressible.

suddenly transparent and permeated by light, are always accompanied by

the sudden expansion and subsequent catharsis of the self-transcending

emotions. I have called this the 'earthing' of emotion, on the analogy

of earthing (or 'grounding') an electrically charged body, so that

its tensions are drained by the immense current-absorbing capacity of

'mother earth'. The scientist attains catharsis through the reduction

of phenomena to their primary causes; a disturbing particular problem is

mentally 'earthed' into the universal order. The same description applies

to the artist, except that his 'primary causes' and 'laws of order' are

differently constituted. They derive from mythology and magic, from the

compulsive powers of rhythm and form, from archetypal symbols which arouse

unconscious resonances. But their 'explanatory power', though not of a

rational order, is emotionally as satisfying as that of the scientist's

explanations; both mediate the 'earthing' of particular experiences into

a universal frame; and the catharsis which follows scientific discovery

or artistic "trouvaille" has the same 'oceanic' quality. The melancholy

charm of the golden lads who come to dust because that is the condition of

man, is due to the 'earthing' of our personal predicaments in a universal

predicament. Art, like religion, is a school of self-transcendence; it

expands individual awareness into cosmic awareness, as science teaches

us to reduce any particular puzzle to the great universal puzzle.

he taught his public to see and accept behind the repulsive particular

object the timeless patterns of light, shadow, and colour. We have

seen that the discoveries of art derive from the sudden transfer of

attention from one matrix to another with a higher emotive potential.

The

intellectual aspect

of this Eureka process is closely akin to

the scientist's -- or the mystic's -- 'spontaneous illumination': the

perception of a familiar object or event in a new, significant, light;

its

emotive aspect

is the rapt stillness of oceanic wonder. The

two together -- intellectual illumination and emotional catharsis --

are the essence of the aesthetic experience. The first constitutes the

moment of truth; the second provides the experience of beauty. The two

are complementary aspects of an indivisible process -- that 'earthing'

process where 'the infinite is made to blend itself with the finite,

to stand visible, as it were, attainable there' (Carlyle).

experience of beauty, because the solution of the problem creates

harmony out of dissonance; and vice versa, the experience of beauty can

occur only if the intellect endorses the validity of the operation --

whatever its nature -- designed to elicit the experience. A virgin

by Botticelli, and a mathematical theorem by Poincaré, do not

betray any similarity between the motivations or aspirations of their

respective creators; the first seemed to aim at 'beauty', the second

at 'truth'. But it was Poincaré who wrote that what guided him

in his unconscious gropings towards the 'happy combinations' which

field new discoveries was 'the feeling of mathematical beauty, of the

harmony of number, of forms, of geometric elegance. This is a true

aesthetic feeling that all mathematicians know.' The greatest among

mathematicians and scientists, from Kepler to Einstein, made similar

confessions. 'Beauty is the first test; there is no permanent place

in the world for ugly mathematics', wrote G. H. Hardy in his classic,

A Mathematician's Apology

. Jacques Hadamard, whose pioneer work

on the psychology of invention I have quoted, drew the final conclusion:

'The sense of beauty as a "drive" for discovery in our mathematical field,

seems to be almost the only one.' And the laconic pronouncement of Dirac,

addressed to his fellow-physicists, bears repeating: 'It is more important

to have beauty in one's equations than to have them fit experiment.'

not to mention architects, have always been guided, and often obsessed,

by scientific and pseudo-scientific theories -- the golden section,

the secrets of perspective, Dürer's and Leonardo's 'ultimate laws' of

proportion,* Cézanne's doctrine 'everything in nature is modelled on

the sphere, the cone and the cylinder'; Braque's substitution of cubes

for spheres; the elaborate theorizings of the neo-impressionists; Le

Corbusier's modulator theory based on the so-called Fibonacci sequence of

numbers -- the list could be continued endlessly. The counterpart to

A

Mathematician's Apology

, which puts beauty before rational method,

is Seurat's pronouncement (in a letter to a friend): 'They see poetry in

what I have done. No, I apply my method, and that is all there is to it.'

Both sides seem to be leaning over backwards: the artist to rationalize

his creative processes, the scientist to irrationalize them, so to

speak. But this fact in itself is significant. The scientist feels the

urge to confess his indebtedness to unconscious intuitions which guide his

theorizing; the artist values, or over-values, the theoretical discipline

which controls his intuition. The two factors are complementary; the

proportions in which they combine depend -- other things being equal

-- foremost on the

medium

in which the creative drive finds

its expression; and they shade into each other like the colours of

the rainbow.

The act of creation itself, as we have seen, is based on essentially

the same underlying pattern in all ranges of the continuous rainbow

spectrum. But the criteria for judging the finished product differ of

course from one medium to another. Though the psychological processes

which led to the creation of Poincaré's theorem and of Botticelli's

virgin lie not as far apart as commonly assumed, the first can be

rigorously verified by logical operations, the second not. There seems

to be a crack in Keats's Grecian urn, and its message to sound rather

hollow; but if we recall two essential points made earlier on, the crack

will heal.

The first is that verification comes only postfactum, when the creative

act is completed; the act itself is always a leap into the dark, a dive

into the deeps, and the diver is more likely to come up with a handful

of mud than with a coral. False inspirations and freak theories are as

abundant in the history of science as bad works of art; yet they command

in the victim's mind the same forceful conviction, the same euphoria,

catharsis, and experience of beauty as those happy finds which are

postfactum proven right. Truth, as Kepler said, is an elusive hussy --

who frequently managed to fool even Galileo, Descartes, Leibniz, Pasteur,

and Einstein, to mention only a few. In this respect, then, Poincaré

is in no better position than Botticelli: while in the throes of the

creative process, guidance by truth is as uncertain and subjective as

guidance by beauty.

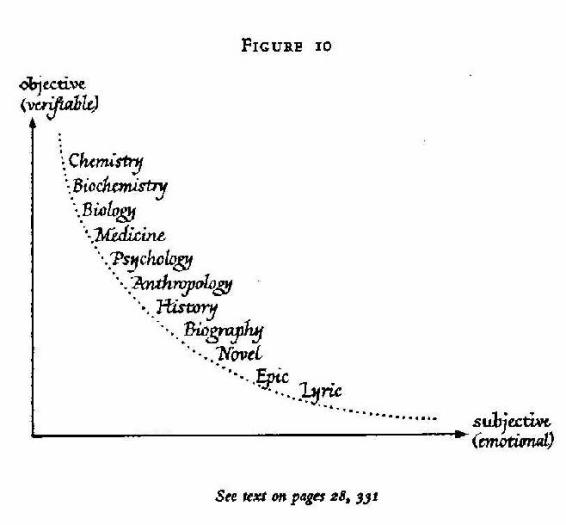

The second point refers to the verifiability of the product after the act;

we have seen that even in this respect the contrast is not absolute, but

a matter of degrees (

Chapter X

). A physical theory

is far more open to verification than a work of art; but experiments,

even so-called crucial experiments, are subject to interpretation; and

the history of science is to a large part a history of controversies,

because the interpretation of facts to 'confirm' or 'refute' a theory

always contains a subjective factor, dependent on the scientific fashions

and prejudices of the period. There were indeed times in the history

of most sciences when the interpretations of empirical data assumed

a degree of subjectivity and arbitrariness compared to which literary

criticism appeared almost to be an 'exact science'.

difference, in precision and objectivity, between the methods of judging

a theorem in physics and a work of art. But I wish to stress once more

that there are continuous transitions between the two. The diagram

on

p. 332

shows one among many such continuous

series. Even pure mathematics at the top of the series had its logical

foundations shaken by paradoxes like Gödel's theorem; or earlier on

by Cantor's theory of infinite aggregates (as a result of which Cantor was

barred from promotion in all German universities, and the mathematical

journals refused to publish his papers). Thus even in mathematics

'objective truth' and 'logical verifiability' are far from absolute. As

we descend to atomic physics, the contradictions and controversial

interpretation of data increase rapidly; and as we move further down

the slope, through such hybrid domains as psychiatry, historiography,

and biography, from the world of Poincaré towards that of Botticelli,

the criteria of truth gradually change in character, become more avowedly

subjective, more overtly dependent on the fashions of the time, and, above

all, less amenable to abstract, verbal formulation. But nevertheless

the experience of truth, however subjective, must be present for the

experience of beauty to arise; and vice versa, the solution of any of

'nature's riddles', however abstract, makes one exclaim 'how beautiful'.

in this computer age we would have to improve on its wording (as Orwell

did on Ecclesiastes): Beauty is a function of truth, truth a function of

beauty. They can be separated by analysis, but in the lived experience of

the creative act -- and of its re-creative echo in the beholder -- they

are inseparable as thought is inseparable front emotion. They signal,

one in the language of the brain, the other of the bowels, the moment

of the Eureka cry, when 'the infinite is made to blend itself with the

finite' -- when eternity is looking through the window of time. Whether

it is a medieval stained-glass window or Newton's equation of universal

gravity is a matter of upbringing and chance; both are transparent to

the unprejudiced eye.

p. 329

.

PROPORTIONS OF THE HUMAN FIGURE

From the chin to the starting of the hair is a tenth part of the figure.

From the chin to the top of the head is an eighth part.

And from the chin to the nostrils is a third part of the face.

And the same from the nostrils to the eyebrows, and from the eyebrows

to the starting of the hair.

If you set your legs so far apart as to take a fourteenth part from

your height, and you open and raise your arms until you touch the line

of the crown of the head with your middle fingers, you must know that

the centre of the circle formed by the extremities of the outstretched

limbs will be the navel, and the space between the legs will form an

equilateral triangle.

The span of a man's outstretched arms is equal to his height.

(From Leonardo's Notebooks, quoted by R. Goldwater and M. Treves,

eds., 1947, p. 51.)

INFOLDING

Let me return once more to the three main criteria of the technical

excellence of a comic work: its originality, emphasis, and economy;

and let us see ho~ far they are applicable to other forms of art.

Originality and Emphasis

From antiquity until well into the Renaissance artists thought, or

professed to think, that they were copying nature; even Leonardo wrote

into his notebook 'that painting is most praiseworthy which is most

like the thing represented'. Of course, they were doing nothing of the

sort. They were creating, as Plato had reproached them, 'man-made dreams

for those who are awake'. The thing represented had to pass through two

distorting lenses: the artist's mind, and his medium of expression,

before it emerged as a man-made dream -- the two, of course, being

intimately connected and interacting with each other.

To start with the medium: the space of the painter's canvas is smaller

than the landscape to be copied, and his pigment is different from

the colours he sees; the writer's ink cannot render a voice nor exhale

the smell of a rose. The nature of the medium always excludes direct

imitation. Some aspects of experience cannot be reproduced at all;

some only by gross oversimplification or distortion; and some only at

the price of sacrificing others. The limitations and peculiarities of

his medium force the artist at each step to make choices, consciously

or unconsciously; to select for representation those features or aspects

which he considers to be relevant, and to discard those which he considers

irrelevant. Thus we meet again the trinity of

selection, exaggeration,

and simplification

which I have discussed before (

Other books

The Way Home by Henry Handel Richardson

So Much for That by Lionel Shriver

What Color Is Your Parachute? by Richard N. Bolles

A Kiss of Blood: A Vamp City Novel by Palmer, Pamela

Touch Me - Complete Collection by Lucia Jordan

William the Fourth by Richmal Crompton

Nature's Destiny by Winter, Justine

So I Married a Rockstar by Marina Maddix

Summon Lyght by Kenra Daniels, Azure Boone

Agent Bride by Beverly Long