The Act of Creation (77 page)

Read The Act of Creation Online

Authors: Arthur Koestler

p. 513

. Cf. Polànyi, 1958, p. 364:

'Behaviourists teach that in observing an animal we must refrain above

all from trying to imagine what we would do if placed in the animal's

position. I suggest, on the contrary, that nothing at all could be known

about an animal that would be of the slightest interest to physiology, and

still less to psychology, except by following the opposite maxim. . . .

p. 516

. This response is mediated either by

resonance (Helmholz's theory) or, more likely, by the locus of maximum

hydraulic pressure in the 'travelling wave'.

p. 517

. The latter assumes that in visual

perception a spatial 'picture' is projected on to the primary optical

cortex, which reproduces the retinal image. But the excitation-pattern in

the auditory cortex has no 'contours' separating figure and background,

and it would be difficult to imagine 'field currents' created by them.

p. 533

. There are strong arguments against

the segmentation of language according to the letters of the written

alphabet (cf. e.g. Paget 1930; Ladefoged in

Mechanization of Thought

Processes

, 1959).

p. 537

. There exist of course both innate

and acquired preferences for choosing one system of 'coloured filters'

rather than another as a criterion of equipotentiality. Two notes an

octave apart sound more 'similar' to man and rat than two notes close

together. Evidently the nervous system finds it for its own 'intents

and purposes' more convenient to regard two frequencies of the ratio

2p:p as more similar than two frequencies of the ratio p:(p - r).

p. 539

. The protracted controversy about

the existence of progressive, systematic changes in perceptual traces

('levelling' and 'sharpening') was unfortunately restricted to one type of

change only -- the reduction of 'dynamic stress' in the physical trace,

predicted by Gestalt physiology -- see Wulf, quoted by Koffka (1935);

Hebb and Foord (1954). No psychologist would dare to deny that 'memory

plays us false'; but its confidence-tricks are evidently not of the

grossly mechanical type, divorced from the subject's living experience,

which Köhler's theory of cortical field-processes demanded.

p. 540

. 'Negative recognition' could be

called the

unconscious

variety of Woodworth's (1938) 'schema

with correction'.

MOTOR SKILLS

In the process of becoming an expert typist, the student must go

through the whole range of learning processes variously classified as as

instrumental conditioning, sign-learning, trial and error, rote and place

learning, insight. He is, of course, quite unaware of these categories --

which, in fact, overlap at almost every stage. The essence of the process

is the step-wise integration of relatively simple codes of behaviour into

complex and flexible codes with a hierarchic structure. This conclusion

was actually reached (although expressed in different words) in the

1890s by Bryan and Harter [1] -- then buried and forgotten for nearly

half a century. Woodworth was one of the few experimental psychologists

who kept harking back to the subject. The following is taken from his

summary of Bryan and Harter's

Studies on the Telegraphic Language. The

Acquisition of a Hierarchy of Habits

. [2]

'word', and 'context' levels. The letter habit is acquired by 'serial

learning'. But no chain-response theory can account even for this

first step in acquiring the skill -- for the simple reason that the

homogeneous dots and the homogeneous dashes of the Morse sequence

offer no distinguishable characteristics for the forming of specific

S.-R. connections. The letter 'u' is transmitted by dot-dot-dash; the

letter 'w' by dot-dash-dash. In terms of S.-R. theory, the finger-movement

made in sending the first dot is the initial part-response which

triggers the chain, its kinaesthetic sensation acting as a stimulus

which calls out the next response. But the correct response to the

same

stimulus will be

either

dot or dash; nothing in the

nature of the stimulus itself indicates what the next response should

be; the response is determined at this and each following step not

by the preceding stimulus but by the total pattern. The habit cannot

be represented by a linear series: . -- -- > -- -- -- > . -- .

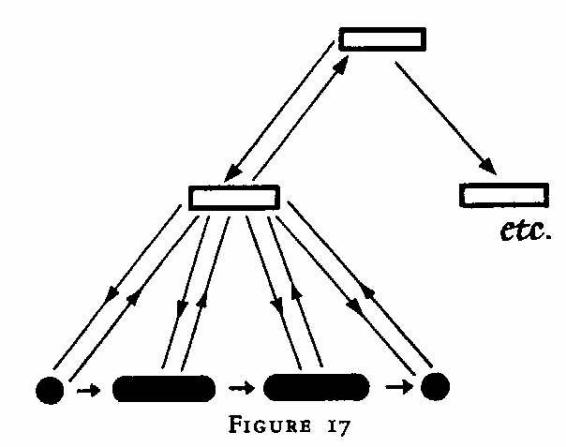

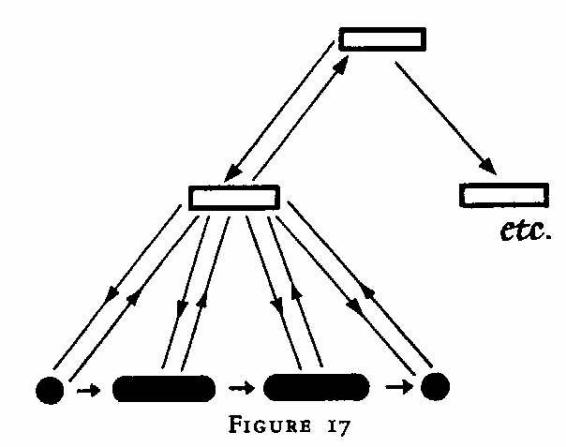

it can only be represented as a two-tired hierarchic structure:

The related skill of touch-typing was studied by Book [3], who wired his

The related skill of touch-typing was studied by Book [3], who wired his

machines to time every move made by the experimental subjects. In this

case the letter habit is acquired by 'place-learning' -- the keyboard

is hidden from the student by a screen, and he is required to form a

'map' of its layout in his head. This map, one supposes, is structured

by a simple co-ordinate-system: the fixed resting position of the ten

fingers on the third row of the keyboard; the result is a kind of simple

'maze' with variable target positions. But when, after a certain amount

of hit and miss, the letter habit had been mastered:

units. The records showed 'no pauses between phrases' but an even flow;

and here, too, 'the eyes [on the text to be copied] were well ahead of

the hands' -- to enable the typist to take in the meaning.

As a third example let us consider learning to play the piano (though I

could find no textbook references to this not altogether unusual human

occupation). The 'letter habit' here becomes a 'note habit' -- hitting the

intended black or white key; for 'word' read 'bar' or 'musical phrase';

and so on to more complex integrated patterns. In this case, however,

even the lowest unit of the skill -- hitting the right key -- displays

considerable flexibility. There is no longer, as on the typewriter,

a rigid attribution of each key to one finger; on the piano keyboard

almost any finger can be used, according to circumstances, to hit any key;

several keys may be hit and held at the same time; and a hard or soft

touch makes all the difference to musical quality. (Needless to say,

even the typist's motion-patterns must be adaptable to small portables

and large office machines, and the starting position of the finger varies

according to the preceding stroke. Flexibility is a matter of degrees;

a completely fixed response is, like the reflex arc, an abstraction.)

The skill of hitting the correct piano-key is not acquired by establishing

point-to-point correspondences, but primarily by practising the various

scales; these superimpose, as it were, structured motions on to the

keyboard, sub-structured into triads, septims, etc. At an advanced stage,

when improvization has become possible, the left hand will learn to

accompany the right, which acts as a 'pace-maker' -- a glorified form of

the magnet effect in the gold-fish (p. 438); but the left can also act in

relative independence, according to the commands of the score. At this

level we have approximately the following state of affairs: the visual

input consists in two groups of parallel rows (staves) of coded signals,

of which the upper series must be referred to the right, the lower to

the left hand. In the course of this procedure both rows of signals

must be de-coded and re-coded. The symbols on the two rows are usually

in different parallel codes ('violin clef' for the right, 'bass clef'

for the left). Moreover, there are 'key signatures' -- sharp and flat

signs -- at the beginning of a section, which modify the 'face value'

of the notes; there are symbols which indicate the timing and duration of

notes; and overall instructions regarding loudness, tempo and mood. All

these part-dependent, part-independent de- and re-coding operations for

both hands must proceed simultaneously, in the psychological present,

and more or less automatically.

On an ever higher level, the concert pianist develops a repertory of

oeuvres that he can 'trigger off' as units and play by heart -- though

some of these units may be an hour long. Once again we must assume

that this is done by a combination of several interlocking hierarchies,

each articulated into sub-wholes and the sub-wholes thereof.

Then there is improvisation. It need not be creative; the bar-pianist who,

half asleep, syncopates Chopin and trails off into some variation of his

own, is not a composer; but he has gained additional flexibility -- more

degrees of freedom -- in the practice of his skill. And finally there is

the creative act: the composer who weaves his threads into new patterns,

and the interpreter who sheds new light on existing patterns.

The learning process is, somewhat paradoxically, easiest to visualize

as a reversal of the hierarchic sequence of operations which will

characterize performance when learning is completed. When the typist

copies a document, the sequence of operations is initiated on the semantic

level, then branches down into successive lower levels with increasingly

specific 'fixed action-patterns' -- 'word-habits' and 'letter-habits

'; terminating in the 'consummatory act' of the finger muscles. The

impulses arborize downwards and outwards, whereas learning proceeds in

the reverse direction: the tips of the twigs of the future tree are the

first to come into existence; the twigs then grow together centripetally

into branches, the branches merge into the trunk. It strikes one as a

very artificial procedure; but the type of mechanical learning we have

discussed, where the discrete base-units must be stamped in bit by bit,

is indeed an artificial procedure. The difference between this method

of learning through trial and error and learning 'by insight' becomes

glaringly obvious if you compare what happens during an elementary

violin lesson and an equally elementary singing lesson. The choir boy

can rely on his innate, multiple auditory-vocal feedbacks -- operating

through the air, through his bones, and through proprioceptive sensations

from his vocal tract -- to control his voice. But there exist no innate

feedbacks between the violin student's cochlea and finger-muscles, to

control their motions. No amount of theoretical insight into the working

of the instrument can replace this handicap; it can only be overcome by

supplementing insight with trial and error. In other words, human beings

are biologically less 'ripe' for learning the violin than for learning

to sing. If evolution were to produce a super-cricket or cicada sapiens,

the opposite may be true.

To put it in a different way: the built-in feedbacks of the auditory-vocal

apparatus provide a

direct insight

into the rightness or

wrongness (singing out of tune) of the response; they permit an

immediate 'perception of relations' -- which is Thorpe's definition of

insight. But once more, this insight is far from absolute: when it comes

to professional singing, a heart-breaking amount of drill is required. The

pupil is often taught the proper techniques of breathing with his hand

on the teacher's stomach -- because his insight into, and control of,

his own physiological functions is limited. Verbal instructions are of

little help, and are sometimes a hindrance, in the acquisition of muscle

skills; to become clever with one's hands, or one's feet in dancing,

requires a kind of muscle training which defies classification as either

insightful or trial-and-error learning.

I have repeatedly mentioned the mysteries of riding a bicycle: nobody

quite knows how it is done, and any competent physicist would be inclinded

to deny a priori that it can be done. However, as a two-legged primate,

man has an innate 'ripeness' for the acquisition of all kinds of postural

and balancing skills such as skating, rock-climbing, or walking the

tight-rope; accordingly, the hierarchy of learning processes in the case

of the cyclist starts on a higher level of already integrated sub-skills,

than in the examples previously discussed. Broadly speaking, the pupil

must turn the handle-bar in the direction he is falling, which will

make him tend to fall in the opposite direction, and so forth, until he

gradually 'gets the feel' of the amount of correction required. This is

certainly trial-and-error learning in the sense that errors are punished

by a fall; but the trials are by no means random, and the errors are

all in the right direction -- they merely over- or under-shoot she

mark. The code which is formed by successive adjusments of the neural

'servo-mechanism' is presumably of the analogue-computer type -- and

the same applies probably to dancing, skating, or tennis-playing.

But once the skill has been mastered and formed into a habit, its

integrated pattern is represented as a unit on the next-higher level in

the hierarchy, and can be triggered off by a single (verbal or nonverbal)

command. To take a more complicated example: the soccer-player must

acquire a variety of basic routines of taking command of the ball --

'stopping' it with foot, thigh, chest, or head; volleying it in flight

without stopping; kicking it with the instep, the inner or outer side-wall

of the boot; dribbling, passing, and shooting at the goal, etc. When

these elementary, yet very complex, techniques have been mastered,

each of them will become a self-contained sub-skill in his repertory,

and he will be able to decide, in a split second, which of them to employ

according to the layout of the field. The decision whether to shoot or

pass is based on discrete yes-no alternatives of the digital type; but

the execution of the actual move -- shooting, passing, etc. -- seems

to require an analogue-computer type of code. A further step down the

'analogue' process of flexing the leg-muscles for a pass of appropriate

length is again converted into the digital on-off processes in individual

motor units; while on the top level a fluid strategy is converted into

discrete tactical decisions.

. Cf. Polànyi, 1958, p. 364:

'Behaviourists teach that in observing an animal we must refrain above

all from trying to imagine what we would do if placed in the animal's

position. I suggest, on the contrary, that nothing at all could be known

about an animal that would be of the slightest interest to physiology, and

still less to psychology, except by following the opposite maxim. . . .

p. 516

. This response is mediated either by

resonance (Helmholz's theory) or, more likely, by the locus of maximum

hydraulic pressure in the 'travelling wave'.

p. 517

. The latter assumes that in visual

perception a spatial 'picture' is projected on to the primary optical

cortex, which reproduces the retinal image. But the excitation-pattern in

the auditory cortex has no 'contours' separating figure and background,

and it would be difficult to imagine 'field currents' created by them.

p. 533

. There are strong arguments against

the segmentation of language according to the letters of the written

alphabet (cf. e.g. Paget 1930; Ladefoged in

Mechanization of Thought

Processes

, 1959).

p. 537

. There exist of course both innate

and acquired preferences for choosing one system of 'coloured filters'

rather than another as a criterion of equipotentiality. Two notes an

octave apart sound more 'similar' to man and rat than two notes close

together. Evidently the nervous system finds it for its own 'intents

and purposes' more convenient to regard two frequencies of the ratio

2p:p as more similar than two frequencies of the ratio p:(p - r).

p. 539

. The protracted controversy about

the existence of progressive, systematic changes in perceptual traces

('levelling' and 'sharpening') was unfortunately restricted to one type of

change only -- the reduction of 'dynamic stress' in the physical trace,

predicted by Gestalt physiology -- see Wulf, quoted by Koffka (1935);

Hebb and Foord (1954). No psychologist would dare to deny that 'memory

plays us false'; but its confidence-tricks are evidently not of the

grossly mechanical type, divorced from the subject's living experience,

which Köhler's theory of cortical field-processes demanded.

p. 540

. 'Negative recognition' could be

called the

unconscious

variety of Woodworth's (1938) 'schema

with correction'.

MOTOR SKILLS

In the process of becoming an expert typist, the student must go

through the whole range of learning processes variously classified as as

instrumental conditioning, sign-learning, trial and error, rote and place

learning, insight. He is, of course, quite unaware of these categories --

which, in fact, overlap at almost every stage. The essence of the process

is the step-wise integration of relatively simple codes of behaviour into

complex and flexible codes with a hierarchic structure. This conclusion

was actually reached (although expressed in different words) in the

1890s by Bryan and Harter [1] -- then buried and forgotten for nearly

half a century. Woodworth was one of the few experimental psychologists

who kept harking back to the subject. The following is taken from his

summary of Bryan and Harter's

Studies on the Telegraphic Language. The

Acquisition of a Hierarchy of Habits

. [2]

The beginner first learns the alphabet of dots and dashes. Each letterLet us call these three stages of habit-formation the 'letter',

is a little pattern of finger movements in sending, a little pattern of

clicks in receiving. It is something of an achievement to master these

motor and auditory letter habits. At this stage the learner

spells the words in sending or receiving. With further practice he

becomes familiar with word-patterns and does not spell out the common

words. The transition from the letter habit to the word-habit

stage extends over a long period of practice, and before this stage

is fully reached a still more synthetic form of reaction begins

to appear. "The fair operator is not held so closely to words. He

can take in several words at a mouthful, a phrase or even a short

sentence." In sending he anticipates, as in other motor performances;

but in receiving, he learns to "copy behind", letting two or three words

come from the sounder before he starts to copy. Keeping a few words

behind the sounder allows time for getting the sense of the message.

'word', and 'context' levels. The letter habit is acquired by 'serial

learning'. But no chain-response theory can account even for this

first step in acquiring the skill -- for the simple reason that the

homogeneous dots and the homogeneous dashes of the Morse sequence

offer no distinguishable characteristics for the forming of specific

S.-R. connections. The letter 'u' is transmitted by dot-dot-dash; the

letter 'w' by dot-dash-dash. In terms of S.-R. theory, the finger-movement

made in sending the first dot is the initial part-response which

triggers the chain, its kinaesthetic sensation acting as a stimulus

which calls out the next response. But the correct response to the

same

stimulus will be

either

dot or dash; nothing in the

nature of the stimulus itself indicates what the next response should

be; the response is determined at this and each following step not

by the preceding stimulus but by the total pattern. The habit cannot

be represented by a linear series: . -- -- > -- -- -- > . -- .

it can only be represented as a two-tired hierarchic structure:

machines to time every move made by the experimental subjects. In this

case the letter habit is acquired by 'place-learning' -- the keyboard

is hidden from the student by a screen, and he is required to form a

'map' of its layout in his head. This map, one supposes, is structured

by a simple co-ordinate-system: the fixed resting position of the ten

fingers on the third row of the keyboard; the result is a kind of simple

'maze' with variable target positions. But when, after a certain amount

of hit and miss, the letter habit had been mastered:

further practice gave results unexpected by the learner. He foundYet even phrases ending with a full stop did not prove to be the highest

himself anticipating the sequence of finger movements in a short,

familiar word. Habits were developing for groups of letters such

as prefixes, suffixes, and short words. . . . 'A word simply means

a group of movements which I attend to as a whole. I seem to get

beforehand a sort of feel of the whole group'. . . . The single

letters were no longer thought of and each word became an automatic

sequence. . . . Familiar phrases were similarly organized, the thought

of the phrase calling out the whole series of connected movements. [4]

units. The records showed 'no pauses between phrases' but an even flow;

and here, too, 'the eyes [on the text to be copied] were well ahead of

the hands' -- to enable the typist to take in the meaning.

As a third example let us consider learning to play the piano (though I

could find no textbook references to this not altogether unusual human

occupation). The 'letter habit' here becomes a 'note habit' -- hitting the

intended black or white key; for 'word' read 'bar' or 'musical phrase';

and so on to more complex integrated patterns. In this case, however,

even the lowest unit of the skill -- hitting the right key -- displays

considerable flexibility. There is no longer, as on the typewriter,

a rigid attribution of each key to one finger; on the piano keyboard

almost any finger can be used, according to circumstances, to hit any key;

several keys may be hit and held at the same time; and a hard or soft

touch makes all the difference to musical quality. (Needless to say,

even the typist's motion-patterns must be adaptable to small portables

and large office machines, and the starting position of the finger varies

according to the preceding stroke. Flexibility is a matter of degrees;

a completely fixed response is, like the reflex arc, an abstraction.)

The skill of hitting the correct piano-key is not acquired by establishing

point-to-point correspondences, but primarily by practising the various

scales; these superimpose, as it were, structured motions on to the

keyboard, sub-structured into triads, septims, etc. At an advanced stage,

when improvization has become possible, the left hand will learn to

accompany the right, which acts as a 'pace-maker' -- a glorified form of

the magnet effect in the gold-fish (p. 438); but the left can also act in

relative independence, according to the commands of the score. At this

level we have approximately the following state of affairs: the visual

input consists in two groups of parallel rows (staves) of coded signals,

of which the upper series must be referred to the right, the lower to

the left hand. In the course of this procedure both rows of signals

must be de-coded and re-coded. The symbols on the two rows are usually

in different parallel codes ('violin clef' for the right, 'bass clef'

for the left). Moreover, there are 'key signatures' -- sharp and flat

signs -- at the beginning of a section, which modify the 'face value'

of the notes; there are symbols which indicate the timing and duration of

notes; and overall instructions regarding loudness, tempo and mood. All

these part-dependent, part-independent de- and re-coding operations for

both hands must proceed simultaneously, in the psychological present,

and more or less automatically.

On an ever higher level, the concert pianist develops a repertory of

oeuvres that he can 'trigger off' as units and play by heart -- though

some of these units may be an hour long. Once again we must assume

that this is done by a combination of several interlocking hierarchies,

each articulated into sub-wholes and the sub-wholes thereof.

Then there is improvisation. It need not be creative; the bar-pianist who,

half asleep, syncopates Chopin and trails off into some variation of his

own, is not a composer; but he has gained additional flexibility -- more

degrees of freedom -- in the practice of his skill. And finally there is

the creative act: the composer who weaves his threads into new patterns,

and the interpreter who sheds new light on existing patterns.

The learning process is, somewhat paradoxically, easiest to visualize

as a reversal of the hierarchic sequence of operations which will

characterize performance when learning is completed. When the typist

copies a document, the sequence of operations is initiated on the semantic

level, then branches down into successive lower levels with increasingly

specific 'fixed action-patterns' -- 'word-habits' and 'letter-habits

'; terminating in the 'consummatory act' of the finger muscles. The

impulses arborize downwards and outwards, whereas learning proceeds in

the reverse direction: the tips of the twigs of the future tree are the

first to come into existence; the twigs then grow together centripetally

into branches, the branches merge into the trunk. It strikes one as a

very artificial procedure; but the type of mechanical learning we have

discussed, where the discrete base-units must be stamped in bit by bit,

is indeed an artificial procedure. The difference between this method

of learning through trial and error and learning 'by insight' becomes

glaringly obvious if you compare what happens during an elementary

violin lesson and an equally elementary singing lesson. The choir boy

can rely on his innate, multiple auditory-vocal feedbacks -- operating

through the air, through his bones, and through proprioceptive sensations

from his vocal tract -- to control his voice. But there exist no innate

feedbacks between the violin student's cochlea and finger-muscles, to

control their motions. No amount of theoretical insight into the working

of the instrument can replace this handicap; it can only be overcome by

supplementing insight with trial and error. In other words, human beings

are biologically less 'ripe' for learning the violin than for learning

to sing. If evolution were to produce a super-cricket or cicada sapiens,

the opposite may be true.

To put it in a different way: the built-in feedbacks of the auditory-vocal

apparatus provide a

direct insight

into the rightness or

wrongness (singing out of tune) of the response; they permit an

immediate 'perception of relations' -- which is Thorpe's definition of

insight. But once more, this insight is far from absolute: when it comes

to professional singing, a heart-breaking amount of drill is required. The

pupil is often taught the proper techniques of breathing with his hand

on the teacher's stomach -- because his insight into, and control of,

his own physiological functions is limited. Verbal instructions are of

little help, and are sometimes a hindrance, in the acquisition of muscle

skills; to become clever with one's hands, or one's feet in dancing,

requires a kind of muscle training which defies classification as either

insightful or trial-and-error learning.

I have repeatedly mentioned the mysteries of riding a bicycle: nobody

quite knows how it is done, and any competent physicist would be inclinded

to deny a priori that it can be done. However, as a two-legged primate,

man has an innate 'ripeness' for the acquisition of all kinds of postural

and balancing skills such as skating, rock-climbing, or walking the

tight-rope; accordingly, the hierarchy of learning processes in the case

of the cyclist starts on a higher level of already integrated sub-skills,

than in the examples previously discussed. Broadly speaking, the pupil

must turn the handle-bar in the direction he is falling, which will

make him tend to fall in the opposite direction, and so forth, until he

gradually 'gets the feel' of the amount of correction required. This is

certainly trial-and-error learning in the sense that errors are punished

by a fall; but the trials are by no means random, and the errors are

all in the right direction -- they merely over- or under-shoot she

mark. The code which is formed by successive adjusments of the neural

'servo-mechanism' is presumably of the analogue-computer type -- and

the same applies probably to dancing, skating, or tennis-playing.

But once the skill has been mastered and formed into a habit, its

integrated pattern is represented as a unit on the next-higher level in

the hierarchy, and can be triggered off by a single (verbal or nonverbal)

command. To take a more complicated example: the soccer-player must

acquire a variety of basic routines of taking command of the ball --

'stopping' it with foot, thigh, chest, or head; volleying it in flight

without stopping; kicking it with the instep, the inner or outer side-wall

of the boot; dribbling, passing, and shooting at the goal, etc. When

these elementary, yet very complex, techniques have been mastered,

each of them will become a self-contained sub-skill in his repertory,

and he will be able to decide, in a split second, which of them to employ

according to the layout of the field. The decision whether to shoot or

pass is based on discrete yes-no alternatives of the digital type; but

the execution of the actual move -- shooting, passing, etc. -- seems

to require an analogue-computer type of code. A further step down the

'analogue' process of flexing the leg-muscles for a pass of appropriate

length is again converted into the digital on-off processes in individual

motor units; while on the top level a fluid strategy is converted into

discrete tactical decisions.

Other books

Conversations with Waheeda Rehman by Kabir, Nasreen Munni, Rehman, Waheeda

Dead by Morning (Rituals of the Night Book 1) by Kayla Krantz

Shape of Fear by Hugh Pentecost

Secrets in the Shadows by T. L. Haddix

I Shall Not Want by Norman Collins

Insurrection (Athena Lee Chronicles Book 5) by T S Paul

Men by Laura Kipnis

Silent Kills by Lawrence, C.E.

Finally Found by Nicole Andrews Moore

Operation: Normal by Linda V. Palmer