The Adventure of English (23 page)

Read The Adventure of English Online

Authors: Melvyn Bragg

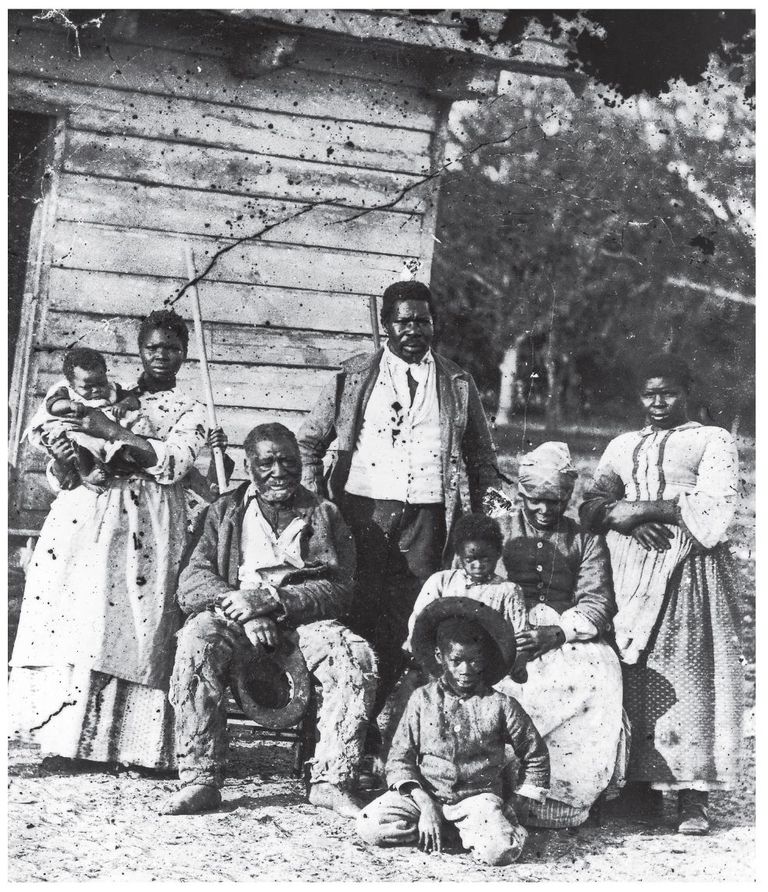

32. Four generations of a South Carolina slave family, photographed in the 1880s. Even today near Charleston can be heard a dialect called Gullah, believed to be close to the English spoken by slaves from Africa.

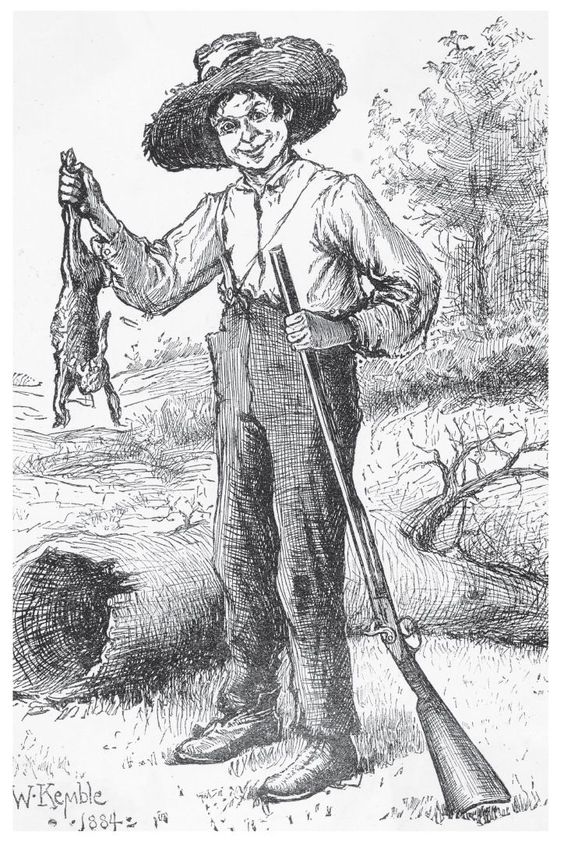

34. Twain's

Huckleberry Finn

, published in 1885, is powerfully laced with black English.

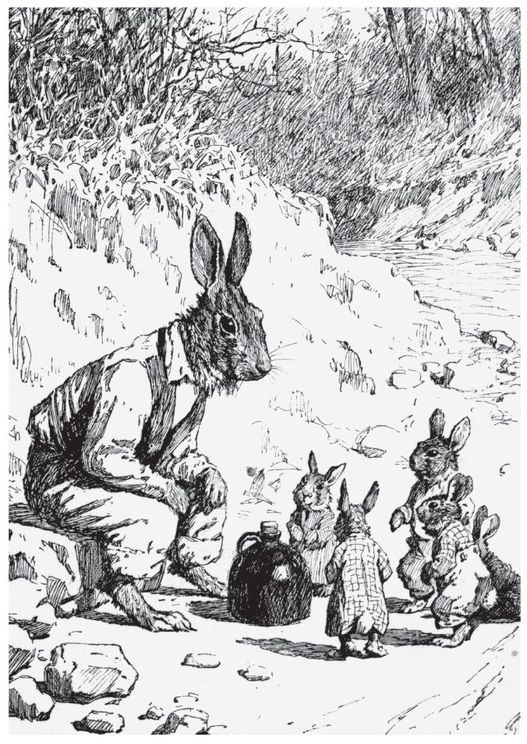

33.

Brer Rabbit

by Joel Chandler Harris, described by Mark Twain as the only master of the “Negro dialect” the country has produced.

35. In 1652 the first coffee houses opened in England and came to be known as “penny universities.”

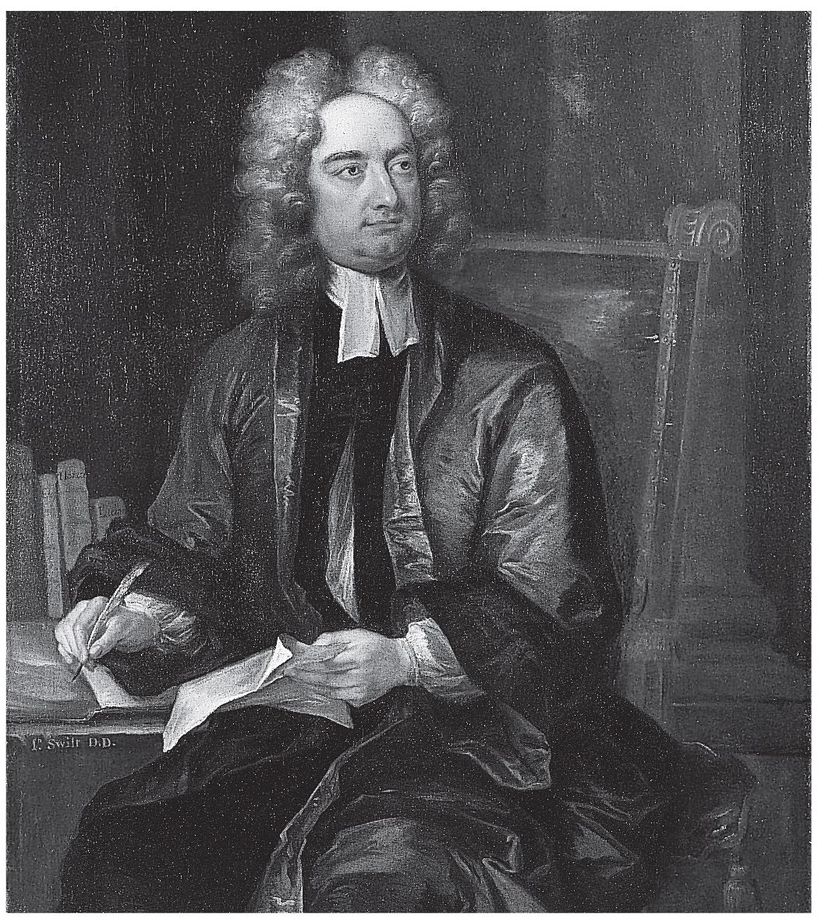

36. Jonathan Swift wrote that a stable, consistently spelled and pronounced English language would “very much contribute to the glory of Her Majesties reign” â but it didn't catch on.

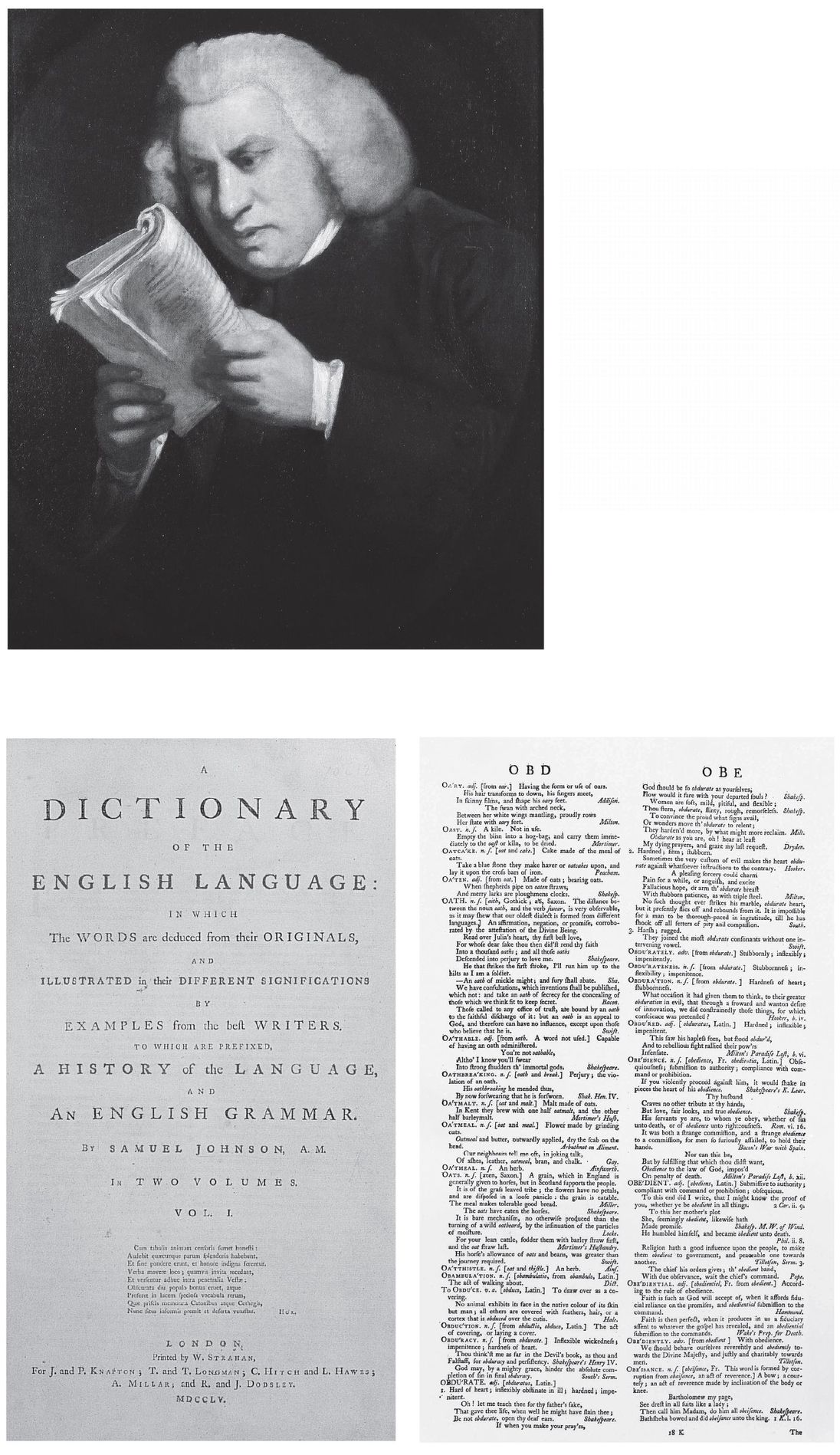

37. Samuel Johnson: the original idea of his great work, published in 1755, was to make “a dictionary by which the pronunciation of our language may be fixed . . . by which its purity will be preserved.”

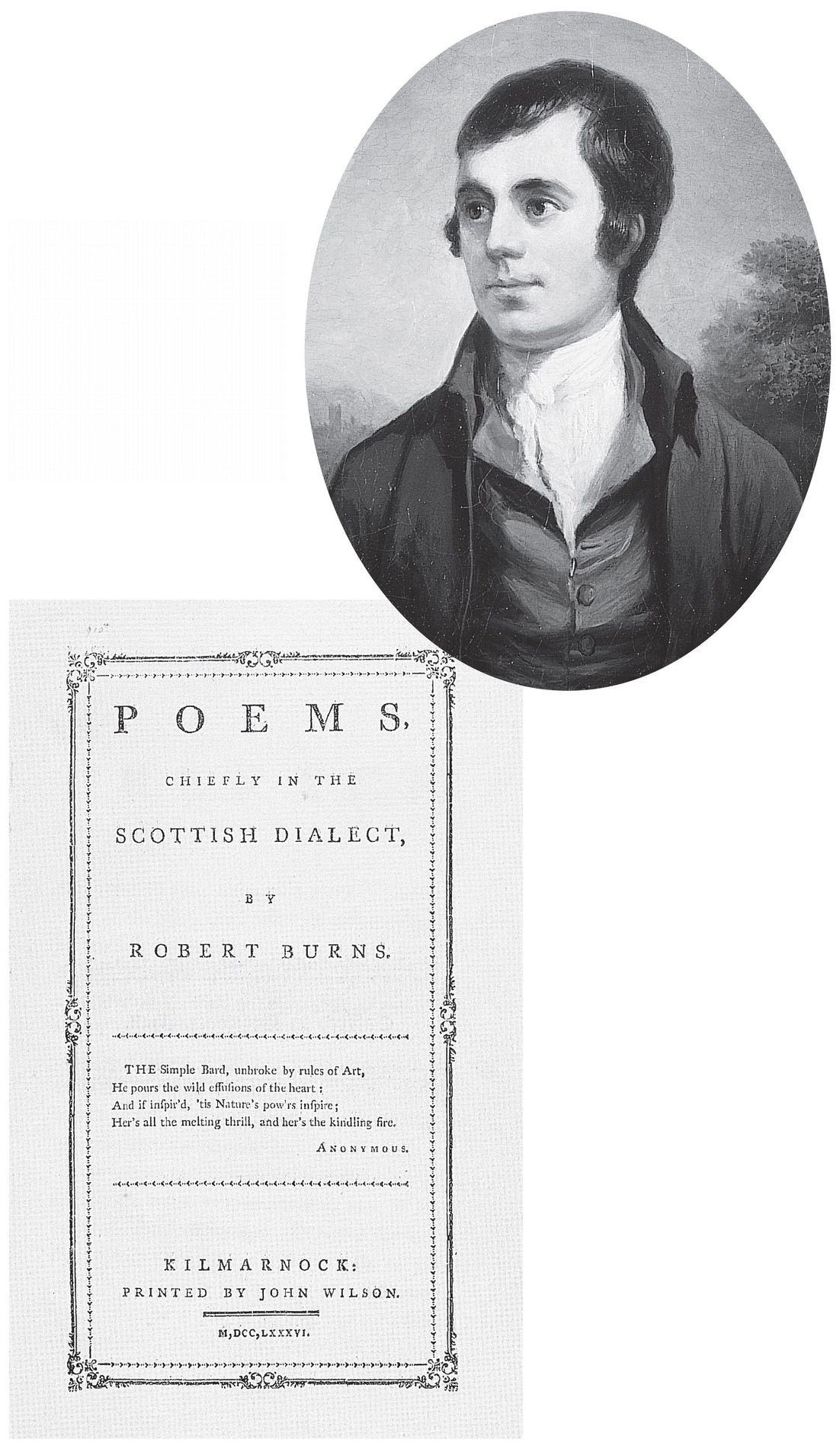

38. Robert Burns' first collection,

Poems Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect,

1786: his language became a powerful touchstone for national identity.

The pidgin developed into creole, which is a language with its own grammar, structures and vocabulary, and out of that came Gullah. The original Gullah is still spoken by about two hundred fifty thousand people, preserved in the amber of history as clearly as the Cornish dialect among eight hundred oyster and crab fishermen on the island of Tangier further north. The vocabulary of Gullah is primarily English, very often derived from dialect words â the words most likely to be spoken by the English sailors; West Country especially. However, studies suggest that somewhere between about three thousand and six thousand words are derived directly from African languages, “gula” for “pig,” for example, “cush” for “bread,” “nansi” for “spider,” “bucksa” for “white man.” It has some highly idiomatic expressions: for instance, “beat on ayun” â mechanic, literally “beat-on-iron”; “troot ma-aut” â a truthful person, literally “truth mouth”; “sho ded” â cemetery, literally “sure dead”; “krak teet” â to speak, literally “crack teeth”; “tebl tappe” â preacher, literally “table tapper”; “daydeen” â dawn; “det rain” â downpour; “pinto” â coffin.

Many African-based Gullah words now appear in Standard English. “Banana” comes from the Wolof language spoken in Senegal; “voodoo” is traceable to the word for “spirit” in Yoruba. Others may include the names of animals: the zebra, the gorilla, the chimpanzee; mixed terms such as “samba,” “mambo” and “banjo,” and the food and plant names “goober,” meaning peanut, “yam” and “gumbo,” meaning okra. African compound words were translated, giving English terms like “bad mouth”; “nitty gritty,” it has been claimed, originated as a term for the grit that accumulated in the bilges of slave ships.

Gullah and African American English share some grammatical features that differ from Standard English. We might hear adjective duplication for emphasis: “clean clean,” not “very clean”; or verb serialisation (“I hear tell say he knows”) and “don” used for the past tense (“I don killed 'em” for “I killed 'em”). Or the use of “be.” “He talkin” means “he is talking” now. “He be talking” means he habitually talks. “We been see” means “we have seen,” “We

been

see” (with the stress) means something that took place some time ago.

Grammatical changes â dropping “is,” using “don't” where English said “does not” â were held up as evidence by some white speakers that the “blacks” could not get the hang of “their” language. In fact what was happening was remarkably similar to what happened when the Saxons and the Danes met head-on across the line of the Danelaw in ninth-century England and changed English grammar for ever. Anything, though, that was thought to “prove” the inferiority of slaves was seized on by the owners, who naturally considered that they owned the language just as much as they owned the slaves. It took some time for scholars to realise and then acknowledge that black speech was not inept white speech but a tributary language of its own which could and did in time enlarge the whole language.

In the same prejudiced manner, the influence of black speech on southern whites was denied for many years despite widely recorded evidence that white children often picked up their language from black nurses and nannies â again we go back, this time to the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, when it was observed and often feared that French-born children would pick up English from their Saxon nurses and nannies. In 1849, Sir Charles Lyell (who had noted that Sanskrit was a four-thousand-year-old source of so many languages, including English) visited the U.S. and, having noted how black and white children were educated together, wrote: “Unfortunately, the whites, in return, often learn from the Negroes to speak broken English, and in spite of losing much time in unlearning ungrammatical phrases, well-educated persons retain some of them all their lives.” It is a consistent theme â children learning and often loving the native language of dialect, and being forced to rid themselves of it when they made their way “up” in a society which depended on the natives being “down.”

It has been argued that the boundaries of southern white dialect are the same as the boundaries of the Confederacy, where slavery was an institution. This was taken to indicate that southern white dialect must be that most heavily influenced by black speech. If true, this gives a fine twist to the racism and the racist language in the slave-owning south. In Georgia, still in 2003, there are words that can be traced back to over twenty African languages.

But generally black speech did not really begin to influence white speech until the great nineteenth-century migrations to northern industrial cities like Chicago. The English language has never been a great respecter of boundaries any more than it takes a great deal of long-term notice of any other attempt to control it. And it was principally through songs and music at the end of the nineteenth and into the twentieth century, as we will describe later, that black culture brought black English into the main arena.

But preparing the way for that came the stories. We know of black poets such as George Moses Horton early in the eighteenth century, but the first real mark made in story-telling were the Uncle Remus stories with their great hero, Brer Rabbit. Uncle Remus, to make life a little difficult, was a white man, “undersized, red-haired and somewhat freckled,” called Joel Chandler Harris. However, according to Mark Twain, in writing about the “Negro dialect,” Harris was “the only master the country has produced.” (There was also a Charles C. Jones, Jr., whose stories were similar but whose fame has not endured.) Harris himself wrote of “the really poetic imagination of the Negro”; he spoke of “the quaint and homely humor which was his most prominent characteristic.” It seems to me to matter very little that Harris was white. What matters is that he was a collector of stories in the “ling” (his word) on the plantations of the south Atlantic states. Who knows if Homer was Greek? The stories he told tell us about that people.