The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II (34 page)

Read The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II Online

Authors: William B. Breuer

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #aVe4EvA

There were two thousand Sinatra fan clubs across the nation. He was receiving more than five thousand letters a week from girls and women, many asking for a date. Sinatra was not overburdened with humility. “I’m riding high, kid,” he told a reporter for the New York Times.

Many American adults were outraged by the Sinatra-mania. George Chat-field, the New York City education commissioner, threatened to file charges against the Voice for encouraging truancy because thousands of teenaged girls were skipping school to attend his concerts. A member of Congress took to the floor to declare that the primary reasons for juvenile delinquency in the United States were the Lone Ranger and Frank Sinatra.

Much of the adult loathing of Sinatra had its roots in an affronted patriotism. It seemed grossly unfair to many that brave boys usually much younger than the singer were being killed and maimed fighting the Germans and Japanese while a skinny entertainer was earning millions of dollars and the adulation of America’s teenage girls.

Failure to serve in uniform was not Sinatra’s fault, however. Several times he was called in to take Army physical examinations, while hordes of weeping bobby-soxers protested this outrage in front of the induction center. Each time he was reclassified 4-F because of a punctured eardrum.

The Army newspaper, Stars and Stripes, summed up the view of most American servicemen and civilian adults: “Mice make women faint, too.”

15

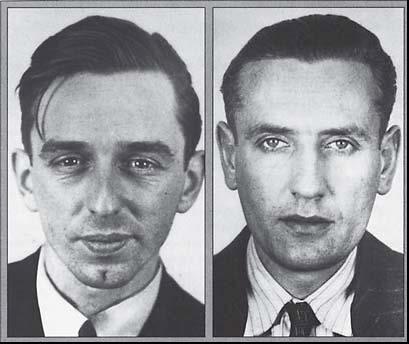

FBI agents in New York City arrested Nazi spies William Colepaugh (left) and Erich Gimpel only one month after they emerged from a U-boat near Bar Harbor, Maine. (FBI)

Dark Intruders Sneak Ashore

N

EAR DAWN ON THE BITTERLY COLD MORNING

of November 29, 1944, the long-range German submarine, U-1230, skippered by Lieutenant Hans Hilbig, was threading its way around the shoals into Frenchman Bay, a body of deep water protruding ten miles into the rugged coast of Maine near the fashionable resort of Bar Harbor. On board were two Nazi spies, Erich Gimpel and William C. Colepaugh. The two men were embarking on Unternehmen Elster (Operation Magpie), a desperate espionage mission to the United States.

Both men had met for the first time and been trained at A-Schule Westen (Agent School West), located on a secluded estate named Park Zorgvliet, between The Hague and suburban Scheveningen in the Netherlands.

Colepaugh, twenty-six years of age, was born and reared in Niantic, Connecticut, on the Long Island Sound and had been a member of the U.S. Navy Reserve when he became dazzled by Adolf Hitler’s promise of a new world order. Colepaugh had made his way to Lisbon, Portugal, as a merchant sailor, then went by land into Germany just before Pearl Harbor.

Gimpel had been born in Merseburg, a small town ninety miles southwest of Berlin. He had been recruited by the Reich Central Security Office to work as a secret agent.

At the A-Schule Westen, Gimpel and Colepaugh were instructed to ferret out technical information on ship construction, rocket experiments, and aircraft production. The key to the cipher they were to use in their radioed reports to Germany was the American advertising slogan: “Lucky Strike cigarettes—they’re toasted!” They were to achieve these goals by exploiting America’s democracy

Dark Intruders Sneak Ashore

173

and gleaning information from newspapers, magazines, technical journals, radio newscasts, and books. It was important, the two spies were told, that this intelligence reach the Third Reich quickly through radio transmissions.

When their espionage course was completed, Gimpel and Colepaugh each was given a Colt pistol, a tiny compass, a Leica camera, a Krahl wristwatch, a bottle of secret ink, powder for developing invisible-ink messages, and instructions for building a radio.

Upon arriving at the Baltic port of Kiel where they were to board Lieutenant Hilbig’s U-1230, the two spies were furnished phony papers. Gimpel’s papers identified him as Edward George Green, born in Bridgeport, Connecticut. They consisted of a birth certificate, a Selective Service registration card showing him registered at Local Board 18 in Boston, and a Massachusetts driver’s license. Colepaugh’s false documents were virtually the same and were made out in the name of William Charles Caldwell, born in New Haven, Connecticut.

Now, on November 29, Gimpel and Colepaugh climbed from Hilbig’s submarine into a rubber raft off bleak Crabtree Point, Maine, and were paddled ashore by two sailors. Along with their espionage accoutrements, the spies carried $60,000 (equivalent to about $700,000 in the year 2002) in a briefcase. A blinding snowstorm was raging as the two men stumbled onto land, but neither had thought to bring along a topcoat or hat.

The Nazi agents bent their heads to the howling wind and trudged inland until they reached a dirt road. Hardly had they begun walking along it than they were caught in the headlights of a car driven slowly by eighteen-yearold Harvard M. Hodgkins, a high school senior who was returning to his nearby home. His father Dana was a deputy sheriff of Hancock County.

Gimpel and Colepaugh continued through snowy woods for about five miles until they reached U.S. Highway 1, where they flagged down a passing taxi. The driver agreed to take them the thirty-two miles to Bangor, Maine, for six dollars. At the Bangor station, the spies caught a train to Portland, Maine, and from there took another train to Boston.

Meanwhile, Deputy Sheriff Hodgkins had returned from a hunting trip and was told by his son of the two lightly dressed strangers in the blizzard. The elder Hodgkins promptly notified the FBI field office in Boston, and agents were rushed to Crabtree Point to launch an investigation.

After spending a night in Boston, Gimpel and Colepaugh entrained for New York on the morning of December 1. Upon arrival at Grand Central Station, they checked a suitcase holding their spying accoutrements and taxied across town to Pennsylvania Station, where they put their cash-filled briefcase in a locker. Then they checked into the Kenmore Hall Hotel at 145 East 23rd Street.

They urgently needed to find an apartment to serve as a shortwave radio studio, and on December 8 they rented a place on the top floor of a townhouse at 39 Beekman Place. “Caldwell” and “Green”—they were using their aliases—

left the townhouse early each morning and returned late in the evening, as though they were legitimate businessmen.

Gimpel and Colepaugh’s enthusiasm for spying began to waver. Forgotten was their mission of digging up technical information. Instead they began wining and dining in plush restaurants and taking in the latest Broadway stage shows. They were sprinkling Hitler’s money around as though it were going out of style. Colepaugh, especially, was on a money-spending binge. When not picking up girls, he was buying expensive suits at a Roger Kent store.

On the night of December 21, Colepaugh waited outside a Robert Reed store in Rockefeller Center while Gimpel was buying a topcoat and a suit to replace his German-made “American” clothing. When Gimpel came out, his companion had vanished.

Colepaugh had taken the subway to the plush St. Moritz Hotel on Central Park, where he spent two nights. Then he went to see an old high school pal, who lived in the borough of Queens. He told his friend that he was a Nazi spy and the nature of his mission. However, he said that he had a change of heart. So with Colepaugh’s approval, his friend called the FBI.

Colepaugh was eager to talk. He told the G-men what Gimpel looked like, that his alias was Edward Green, and that he often bought newspapers at a stand in Times Square.

On the night of December 30, Times Square was cold and windswept. Just before 9:00

P.M.

, two G-men staked out a newsstand and saw a man resembling Gimpel’s description approaching. They pounced on and handcuffed him. The sleuths found $10,574 in cash in his pockets and $4,100 more in his hotel room.

Colepaugh and Gimpel were charged with espionage and tried by a military court at Governor’s Island in New York harbor. They were found guilty, and on February 14, 1945, were sentenced to be executed. Later the verdict was reduced to life in prison. After the war, the two spies were released and sent back to Germany.

16

Robot Bombs Threaten East Coast

D

URING THE FBI’S INTERROGATION

of the two Operation Magpie spies, alarming information surfaced. Before leaving America, they said, their controllers in the German intelligence service had told them that a flotilla of U-boats would follow them. These submarines, the spies swore they had been informed, were outfitted with special rocket-firing devices that would enable the skippers to bombard New York City and Washington from beyond the horizon.

Because William Colepaugh and Erich Gimpel had nothing to gain by disclosing this information, the FBI and the Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI)

Robot Bombs Threaten East Coast

175

took the ominous threat seriously. Evidence was uncovered that indicated these U-boat “special devices” could launch Adolf Hitler’s Vergeltungswaffe (vengeance weapons) against America’s East Coast.

These weapons had long been known to the British and Americans as buzz bombs, and since June 1944 they had been raining on London and other locales in England, causing thousands of deaths and injuries and widespread destruction.

Called the V-1 by the Germans, the buzz bomb was a pilotless aircraft with speeds up to 440 miles per hour, far faster than any Allied fighter could fly. A timing device caused the engine to shut off over a target, and the craft would plunge earthward, exploding with the impact of a 4,000-pound blockbuster bomb.

No doubt the FBI and Navy investigators envisioned the devilish devices’ engines going dead over Washington and crashing into the White House or the Capitol.

Along the eastern seaboard, a network of high-frequency direction finders— electronic sleuths from which no U-boat could evade—disclosed that German radio traffic had rapidly increased in the North Atlantic. Although this evidence was inconclusive, Navy Intelligence took this development as a signal that U-boats were preparing a Pearl Harbor-type sneak attack on New York City and Washington.

On the bleak and frigid morning of January 8, 1945, a bevy of media reporters hovered around Admiral Jonas Ingram, commander of the Eastern Sea Frontier, in a wardroom aboard a warship in New York harbor. The journalists had been promised an “historic press conference.”

Ingram, a heavyset, flat-nosed old salt who had gained national recognition as football coach at the Naval Academy, was one of the service’s most outspoken and colorful characters. Seated at the end of a long table, Ingram said, “Gentlemen we have reason to assume that the [bleeping] Nazis are getting ready to launch a strategic attack on New York City and Washington by robot bombs!”

Reporters are seldom astonished. They now issued gasps of amazement.

“I am here to tell you that [robot bomb] attack is not only possible, but probable as well, and that the East Coast is likely to be buzz-bombed within the next thirty to sixty days.” Ingram paused and stared at his wide-eyed listeners, then added grimly: “The thing to do is not to get excited about it. The explosions may knock out a high building or two, might create a fire hazard, and most certainly would cause casualties. But the [buzz bombs] cannot seriously affect the progress of the war.”

The gruff admiral added: “It may be only two or twelve buzz bombs, but they may come before we can stop them. So I’m springing the cat from the bag to let the Huns [Germans] know that we are ready for them!”

Admiral Ingram’s blunt and terrifying warning was broadcast from coast to coast and splashed across newspapers. A blaring headline in the New York Times screamed:

ROBOT BOMBS ATTACKS HERE HELD POSSIBLE

After sixty days had passed and there were no buzz-bomb strikes, citizens, especially those in New York City and Washington, began to breathe easier.

Had the Germans really been capable of launching these buzz-bomb attacks some four thousand miles from the nearest U-boat bases? Had Ingram’s public warning that the armed forces were on the alert for such an attack caused the Kriegsmarine (German Navy) to call off the project?

17

The Führer Staggers America

A

S CHRISTMAS SEASON 1944 APPROACHED,

heady optimism that the war in Europe was as good as over was rampant on home-front America. Taking their cues from the rose-colored views held by Allied commanders in France, editorial writers comfortably perched in their ivory towers assured readers that Germany was on the brink of collapse.