The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II (9 page)

Read The Air-Raid Warden Was a Spy: And Other Tales From Home-Front America in World War II Online

Authors: William B. Breuer

Tags: #History, #Military, #World War II, #aVe4EvA

Piecing together countless tiny clues, agents of the Federal Bureau of Investigation got on the tail of “Joe Kessler,” and through tedious probing, secured enough evidence to arrest the Nazi spy and eight key members of his spy ring. Blaring newspaper headlines and radio news reports about their trial intensified spy-mania across America.

Mathias F. Correa, an able young U.S. attorney, and his associates presented a huge collection of devastating evidence—all of it collected by the FBI. There were three hundred exhibits and in excess of two thousand pages of interrogations.

After five weeks of listening to the incriminating evidence, the jury returned a guilty verdict against all of Ludwig’s gang. Only Ludwig failed to take the stand in his defense. No doubt he knew that his wife and children in Munich would be handed over to the Gestapo should he talk.

Although the trial was held when the United States was at war, the espionage had taken place before Pearl Harbor, so the defendants were sentenced under peacetime laws. Ludwig was given the maximum penalty—twenty years in prison. Receiving the same penalty was fifty-five-year-old Paul Borchardt, a major in the German army, who had come to the United States in February 1940 under the auspices of a New York City Catholic organization whose function was to spirit refugees out of Hitler’s Europe.

Also receiving a twenty-year term was René Froelich, a thirty-four-yearold native of Germany who was drafted into the U.S. Army in early 1941. Stationed at Fort Jay on Governor’s Island in New York harbor, he was a clerk in the post hospital. Patients from area camps were admitted to the Fort Jay medical facility, where each day a list of new admissions and discharges was drawn up and placed on the desk of the commanding officer. Copies of the lists were stolen by Froelich and handed over to Ludwig.

The spy-ring leader was elated. The lists revealed, for example, that a discharged patient was Sergeant John Smith of the 76th Field Artillery. This

Dismantling a Nazi Spy Network

39

knowledge permitted Ludwig to inform Hamburg that the 76th Field Artillery was stationed at Fort Dix, New Jersey.

In consideration of her cooperation with the FBI, Lucy Boehmler, a nineteen-year-old full-bosomed beauty, was handed the lightest sentence—five years. Born in Germany and brought to New York City at age five, she had been one of Ludwig’s first recruits.

Ludwig had spotted this seemingly all-American schoolgirl at a social function. Bit by bit, he lured her into espionage work. She had been fascinated by his spy tales and finally joined him in search of “excitement.”

The spymaster noted that Lucy possessed a hidden talent that was invaluable in espionage activity—a phenomenal memory. She soon became one of his slickest agents, shielded in part from suspicion by her schoolgirl charm and appearance.

Another agent, Helen Mayer, a Brooklyn housewife, had invited Grumman Aircraft Corporation employees to her home. After plying the unwary dupes with liquor she subtly picked their brains for military secrets. She received a term of fifteen years.

Also sentenced to fifteen years was Hans Pagel, a short, fair-haired youth who was one of Ludwig’s most fanatical agents. Pagel looked harmless enough. But his special job had been to cover the New York waterfront and report on ship sailings, information that was relayed to German U-boats lurking off the eastern seaboard.

Karl Victor Mueller, another of Ludwig’s key foot soldiers, was born in a small Austrian village and became a naturalized American. He was thirty-five years of age, but deep furrows in his brow and a prematurely old countenance caused him to look elderly. He even walked like an old man, his skinny body leaning forward and his head bobbing with each step.

Mueller carried a camera on spy jaunts, and even though he spoke with a thick Teutonic accent, guards and attendants at war production plants and airfields often went out of their way to help the “harmless old man” get the photographs he sought.

Mueller’s true allegiance was to Nazi-occupied Austria, to which he hoped to return as a national hero. Instead he would spend the next fifteen years in a U.S. prison.

Twenty-one-year-old Frederick Edward Schlosser had initially been a reluctant spy. Tall and blond, he had been a pal of Hans Pagel and was engaged to Pagel’s sister.

At first Schlosser had resisted Pagel’s incessant pleas to become a spy, but he finally consented. Ludwig put the youth to work trekking up and down New York City piers culling shipping information. Soon the newcomer was caught up in the excitement, as he termed it, and he even stole a piece of a

new antiaircraft gun from a factory where he worked. He was given twelve years internment.

Carl Herman Schroetter refused to testify against his confederates and was sentenced to ten years. He had an ideal “cover”—skipper of a charter boat, Echo of the Past, based in Miami. Swiss-born Schroetter, who had two sisters living in Germany, cruised the Atlantic coast of Florida while shepherding paid tourists and mailed to Ludwig in New York City a stream of coded messages on ship movements.

A few days after Schroetter entered the federal penitentiary in Atlanta, he hanged himself with a sheet in his cell. Presumably he had anguished over the probable fate of his two sisters at the hands of the Gestapo in Germany.

6

A Debacle in Manhattan

P

IER 88 ON THE NEW YORK CITY WATERFRONT

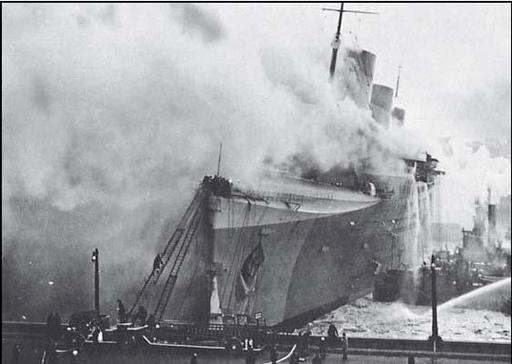

was a beehive of activity in early 1942. Tied up there was the French luxury liner Normandie, which had been in the port in September 1939 when France and England declared war on Nazi Germany and was taken over by the U.S. Navy after France fell in mid-1940. It was being converted to a troop transport.

There was enormous urgency to the renovation task. It was to be finished by February 28, after which the ship would sail to Boston. There ten thousand soldiers would climb aboard, along with weapons and equipment, before sailing into the Atlantic Ocean under sealed orders.

Because of the rush, only cursory checks had been made on the backgrounds of the civilian workers. Likewise, no background investigations were conducted for the hundreds of men who brought building materials and furnishings on board.

On the afternoon of February 9, less than three weeks before the Normandie was to sail for Europe, fire broke out on the gray-painted ship. Flames began whipping rapidly through corridors, and in an hour the liner was an inferno. New York City firemen later would state that the heat was the most intense that they had experienced.

As the flames spread, some three thousand civilian workers, crewmen, and others began scrambling over the sides of the ship or dashing down gangplanks. Hardly had the last man escaped, at 2:32

P

.

M

., than the doomed liner, listing heavily from tons of water poured into her by New York City fireboats, rolled onto her side and lay still in the Hudson’s gray ice.

At the time when every ship was vital to the war effort, the United States had lost its largest transport. Frank Trentascosta was killed when he received a fractured skill in a fall down a ladder. Some two hundred and fifty others suffered burns, cuts, bruises, or lung irritations.

A Debacle in Manhattan

41

Converted French ocean liner Normandie ablaze under mysterious circumstances in New York harbor. (U.S. Navy)

Hardly had the Normandie capsized than several groups launched investigations to pinpoint the blame. A congressional Naval Affairs subcommittee concluded that “the cause of the fire [is] directly attributable to carelessness by [civilian workers].”

Millions of Americans refused to agree. They felt that they knew the real culprits—German saboteurs.

The people’s suspicions would have been reinforced had they known the government investigations had either failed to report on the role played by the Oceanic Service Corporation or else had chosen to keep silent about it. Oceanic had handled the hiring of many of the guards and workers on the Normandie.

Oceanic had been founded by William Dreschel, who had formerly been a superintendent of the North German Lloyd Steamship Line. A few years earlier he had admitted to a House committee that he had supplied $125,000 bail (equivalent to $1.5 million in 2002) for Nazi agents who had been arrested in the United States. In 1938, during the trial of eleven men and women who had been charged with conducting anti-Nazi demonstrations on the deck of the German ocean liner Bremen when it was at a New York City pier, Dreschel was asked by the defense counsel: “Do you owe allegiance to Adolf Hitler?” The answer was a loud: “Yes!”

After Hitler declared war on the United States, the ownership and the identity of the officials of the Oceanic Service Corporation had not been investigated by U.S. officials. So the firm had been placing its people on the Normandie at the pier without question.

Ten days after the Normandie capsized and lay on its side like a huge beached whale, Congressman Samuel Dickstein took to the House floor and stridently charged that William Dreschel had put Nazi guards on the liner.

Calling Dreschel “the nation’s number one spy,” the congressman thundered: “He organized the Oceanic Service Corporation and through that agency was supplying guards to ships, piers, and warehouses in New York City. He placed more than thirty Nazi agents on the Normandie!”

7

The Battle of Los Angeles

A

T A PRESS CONFERENCE

in the Oval Office of the White House on February 17, 1942, President Roosevelt dropped a blockbuster in an offhand manner. He declared that it was possible that an American city could be shelled and bombed without warning. Did he have any particular cities in mind? Yes, New York and Detroit. Curiously, by omission Roosevelt seemed to indicate that Washington was not a target for any enemy force.

Six days after Roosevelt’s pronouncement, as if to dramatize his viewpoint, a Japanese submarine surfaced at night off Goleta, California, eight miles north of Santa Barbara, and pumped twelve to fifteen shells from a deck gun into a large oil complex. A derrick was blown apart, but little other damage was done.

However, it was a psychological victory for the people of Japan. A Tokyo newspaper headline screamed: “Our Submarines Destroy Large U.S. City.”

American intelligence officers concluded that the Japanese submarine had been tuned in to California commercial radio broadcasts because the shelling erupted at the precise time that President Roosevelt was giving one of his folksy fireside chats.

A night after the oil field shelling, three million people in the Los Angeles region were rousted from sleep when sirens began blaring throughout the sprawling complex. Minutes later, scores of powerful searchlights began stabbing long fingers of white into the black sky. Army antiaircraft guns barked and fired more than fifteen hundred rounds at the phantom enemy bomber forces.

Citizens were terrified. Many fled to basements. Others crawled under beds. Adding to the raucous din, police cars dashed about with sirens screeching. An hour after lookouts had spotted the nonexistent bombers, an eerie silence descended upon Los Angeles.

8

“We Poison Rats and Japs”

A

NGER AND NEAR-HYSTERIA

continued to saturate the U.S. home front weeks after the Japanese treachery. These deep emotions intensified after what turned

“We Poison Rats and Japs”

43