The Alley of Love and Yellow Jasmines (30 page)

Read The Alley of Love and Yellow Jasmines Online

Authors: Shohreh Aghdashloo

Sahebjam, portrayed by Jim Caviezel (

The Passion of the Christ

), visits Iran after the revolution and is trapped in a remote Iranian village when his car breaks down. He is approached by a woman—my character, Zahra—who tells him the horrifying story of her niece being stoned to death. The two sit down together while his car is being repaired at the only body shop in the village. He records the conversation with his tape recorder. He must now escape with the story, risking his life to share it with the world.

I had been desperately waiting for someone to bring this barbaric act of punishment to light in the Western world. After reading the screenplay, I let Cyrus know that I would do anything for it to be made and was wondering if he knew any producers who would be willing to risk their money on it. Clearly this was not a commercial film, and not many executives are fond of humanitarian subjects.

He told me that Stephen McEveety and John Shepherd, the founders of the production company M Power, were up to produce the film. I was thrilled knowing it would happen. Steve would not shy away from the material; he was one of the producers of

The Passion of the Christ

.

The movie was shot in Jordan. All the exteriors, including the stoning scene, were filmed in a village called Dana in one month. The rest of the film was shot in Amman, the capital of Jordan, on seven hills in a circle around the center of the town, forming a 360-degree view of this ancient city.

A dedicated cast and crew, along with the good people of the village of Dana, brought to life the horrifying story of man’s brutality in a typically misogynistic society.

Everything about this film was a miracle, including its release. It was not only made in under a year, but it also coincidentally premiered at the time when the Iranian Green Movement began a series of protests following the fraudulent election of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Millions of young Iranians poured out into the streets wearing green tops or headbands or scarves protesting against the regime and demanding Ahmadinejad’s removal from office in 2009.

The movie did what it was supposed to do. It not only enlightened its audience outside Iran but was also an eye-opener to the people who thought that stoning was ancient history. It garnered great reviews and was well received by its audience.

Regretfully, the Green Movement in Iran was defeated and many of the young protesters who marched peacefully on the streets were tortured or killed. Among them was Neda, a young woman who was shot in the neck and died on the street. Someone with a cell phone camera caught images of this tragedy, which then horrified the world.

M

ahmoud Ahmadinejad came to power in Iran through a fraudulent election. His second term will expire in 2013. Although the Green Movement, which had asked for a fair election, has gone underground now, it is my hope that they will advance their cause in 2013 and that the blood of young people like Neda would not have been shed in vain.

Slowly but surely, the people of the Middle East are losing their fear and gaining their freedom. Thousands of Tunisians, Egyptians, Yemenis, Syrians, and others are marching, striving to build nations where no citizen is jailed, beaten, or killed because they speak the truths within their minds and hearts. They seek jobs, housing, and wages that allow proud men and women to provide for their families. They are demanding the liberty to elect governments that for the first time ever will speak in their name.

I have watched the images of people in Tunis, Cairo, and Sana’a with a mixture of elation, hope, foreboding, and, yes, fear. And I pray that in the places located beyond the reach of television people do not lose their voice to fear, but rather find the call for democracy. For Americans, free speech and free pursuit of happiness are easy and expected, but for nearly everyone living in the Middle East, they are neither.

I was born in Iran, and I lived there as a young woman during the 1979 revolution. Thirty-four years later, I have seen many moments in which history has indeed repeated itself. Back in 1979, Iranians of every background lost their fear and found their voices. Together, they marched in the streets, as neither the Shah nor his secret police could silence their piercing, full-throated demands for freedom, democracy, and fundamental respect. The Shah was overthrown, only to be replaced by the Islamic Republic that today persecutes and imprisons any citizen who questions its politics. Those who fought for Iran’s liberation thought that nothing could be worse than the Shah. Unfortunately they were wrong.

May the fate that has befallen Iran never place its hands upon the freedom struggles taking place now throughout the region.

Finally, fitfully and fearfully, many of the region’s autocrats are hearing the voices of their people. But will they listen to their message? To the world, the message from my Middle Eastern brethren is loud and clear: no more oppression, no more dictatorship, and no more hopelessness. This new generation of liberators is marching bravely for the right to choose their fate.

Thomas Jefferson wrote, “When people fear their government, there is tyranny; when government fears the people, there is liberty.”

This is what I wish for my birth country, Iran.

May once again the younger generation of Iran pass through the love alleys in the springtime, hand in hand, and recite poetry to each other beneath the heaving yellow jasmines on the walls, in a free society.

WHILE FINISHING THIS

book, I am in the midst of a family reunion in Calabasas. My mother has come to stay with me for a couple of months, as my father passed away six years ago from a stroke. My brothers are all here with me. Shahram has come in from London, where he now is involved in the field of social work. Shahriar has made his way from Istanbul to San Diego, where he now sells pharmaceutical products. And Sean—formerly Shahrokh—lives in Hawaii as an I.T. engineer for one of Donald Trump’s hotels. My daughter, Tara-Jane, is currently a graduate student studying film at Chapman University. A free spirit, she also has a band, and like Houshang and I once did, she tours around the United States with her band called Aerial Stereo. Houshang is busy being creative and writing new plays. At night we stay up until 3:00 a.m. reminiscing, laughing, and crying about yesterday, when we were young.

My brothers and I purchased live silkworms or caterpillars, ten or twenty at a time, from the markets when we were kids, and placed them in a shoe box on a bed of thoroughly washed green leaves from our neighbor’s mulberry tree that had generously laid its branches on our roof. We then kept replacing the dried, toothed leaves with fresh ones while the silkworms were weaving and creating colorful cocoons with their saliva, just like a cobweb. Some people think silk is made from the silkworm, though it is actually made from the cocoons of a silk moth. Their growth process was like that of a butterfly. We watched their metamorphoses in awe as the silk moths or white butterflies emerged, leaving their colorful cocoons behind for us to collect.

First and foremost I would like to thank my friend and manager, Tamara Houston, who encouraged me to take my bits and pieces of writings seriously, and to write my memoir.

I would also like to thank my editor, Claire Wachtel, for her patience and advice, and all the members of my great team at HarperCollins for their enthusiasm, support, and love.

Many thanks to all of my friends who have patiently waited a year and a half for me to finish writing this book so we can party again.

Thanks, too, to all of my fellow Iranians for their unflagging support of my work.

I am also so grateful to my mother and my brothers for standing by me in pursuing my dreams, including in writing this book.

My father, Anushiravan Vaziritabar, passed away in 2006. We saw each other only a handful of times in the thirty years since the Iranian revolution in 1979, when I left behind my beloved family; my dog, Pasha; my colleagues and friends; and my birth country, Iran, in pursuit of freedom and democracy. I could not even visit him at his deathbed for fear of losing my life over my beliefs. Instead, I spent hours on the phone with my mother at his side, to listen to his last weakening breaths.

The news of my father’s death came early in the morning when I was about to shoot a scene for a new television drama. I was in a state of denial at first and turned my back to the bearer of the bad news. I had lost a noble man whose unconditional love, wisdom, and guidance had brought me here.

My mind filled with images of my father; they flew before my eyes just like shooting stars. I was picturing him with my three brothers and me, helping us with our homework and the multiplication table after school, playing backgammon and solving puzzles with us on the weekends. He took us to hospitals twice a year, and had us share our donations of sweets and fruits with the disadvantaged patients who had no visitors. It was his way of teaching us.

I specifically remember the day he taught me how to waltz to “The Blue Danube.” I was sixteen years old and proud to watch my parents dancing a waltz or tango so effortlessly and in total harmony at our family parties and weddings. One two three, one two three, says my father. I am taking the steps back and forth, holding onto my father’s arms, spinning around, occasionally stepping on my father’s toes. He is looking at me with pride and joy.

I spent the rest of that day mourning his loss in silence, feeling proud of being so lucky to have him in my life and to have him with me now and forever.

S

HOHREH

A

GHDASHLOO

won the Emmy Award for Outstanding Supporting Actress for HBO’s

House of Saddam

and was the first Iranian actress to be nom

inated for an Academy Award for her role in

House of Sand and Fog

. She has starred in the Fox series

24

, and has been featured in a number of television shows and films. Born and raised in Tehran, she now lives in Los Angeles.

Visit

www.AuthorTracker.com

for exclusive information on your favorite HarperCollins authors.

Cover design by Robin Bilardello

Cover photograph © Brian Braff

The names and identifying characteristics of some of the individuals featured throughout this book have been changed to protect their privacy.

THE ALLEY OF LOVE AND YELLOW JASMINES. Copyright © 2013 by Shohreh Aghdashloo. All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the nonexclusive, nontransferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, downloaded, decompiled, reverse-engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins e-books.

All photographs are courtesy of the author unless otherwise noted.

FIRST EDITION

ISBN 978-0-06-200980-7

EPub Edition © JUNE 2013 ISBN: 9780062262127

13 14 15 16 17 OV/RRD 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

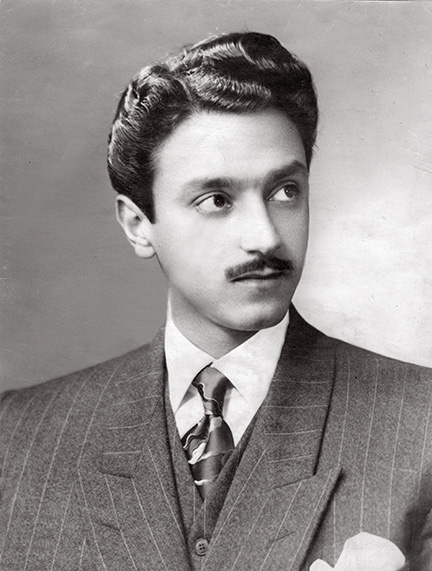

My father, Anushiravan Vaziritabar. “Do not punish children, love them and treat them with dignity, so they would know better,” said my father.