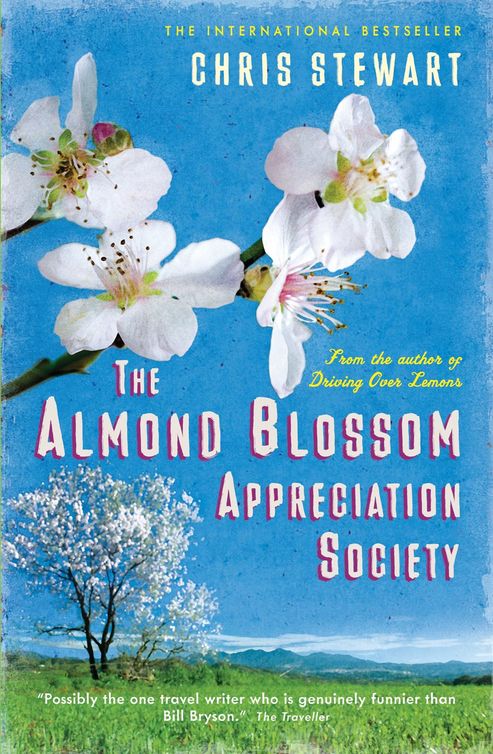

The Almond Blossom Appreciation Society

Read The Almond Blossom Appreciation Society Online

Authors: Chris Stewart

A SORT OF SEQUEL TO

D

RIVING

O

VER

L

EMONS

AND

A P

ARROT IN A

P

EPPER

T

REE

WITH AUTHOR INTERVIEW

The longer I live the more I realise how much we depend upon one another to do everything. All the usual suspects know who they are, and I hope they are aware of my gratitude, but just in case… 1001 thanks to Nat Jansz, my miraculously understanding and skilful editor, without whom this book would not have been possible, and to Mark Ellingham, publisher and long-time friend. M

OROCCO

wouldn’t be half as nice without the hospitality and generosity of Mohammed Benghrib. In Spain, José Guerrero remains a constant source of inspiration and fun; Matias Morales and Manolo del Molinillo keep me rooted, and continue to show me how to get things done; Fernando and Jesús of Nevadensis

(www.nevadensis.com)

have got me out of more tricky situations than they’ve got me into; Michael Jacobs makes me laugh and think; Paco Sánchez and José Pela have been the finest

tertúlia

companions; my sisters Carole and Fiona have been sterling supporters; and above all I owe everything to Ana and Chloë, who live these books with me, and are always there when I need a little comfort and joy.

In addition, C

HRIS

S

TEWART AND

S

ORT

O

F

B

OOKS

thank our invaluable design and production team: Peter Dyer, Henry Iles, Nikky Twyman, Miranda Davies, and to Paul Nobbs at Clays.

B

LACK AND WHITE PHOTOS

by David Aspinall, Chloë Stewart, John Mullen, Mark Ellingham, Nevadensis, Pepe Vílchez, James McConnachie, Carl Sandeman and Chris Stewart.

A

T THE BEGINNING OF THIS YEAR,

my daughter Chloë and I decided that we had to get fit, and that the best way to do this would be to create a running track in the riverbed. We go there every evening now and our pounding feet have marked out a fairly clear circuit.

The grass is long and makes a pleasant thripping noise as you race along, and in spring the ground is sprinkled with dandelions and daisies which grow so dense that, through half-shut eyes, you might be running through a field of cream. The track, however, remains just a bit too

rustic for a good sprint. You have to be careful to hop over the thistles, skip to avoid an ankle-cracker of a stone, and cut in close to the

gayomba,

or Spanish broom, on the third turn, while ducking your head to avoid a poke in the eye. The second turn is between the third and fourth

euphorbia

bush and the start and finish is at the tamarisk tree where we hang our sweaters, and afterwards, if it’s sunny, rest in the wispy shade. The going is soft sandy turf and sheep turds.

As we returned from our run the other night Chloë called me excitedly to the gate: ‘Quick, Dad! Come and have a look at this!’ I turned back and looked where she was pointing. There, battling its way across the track was a dung beetle doing what dung beetles do, rolling a ball of dung. I was instantly captivated: a dung beetle is one of the great sights of the insect world, the determination and purpose of its Sisyphean labour putting you in mind of the crazed industry of ants, except that

Scarabaeus semipunctatus

operates in pairs or alone.

This particular beetle had lost its jet-black shine under a thick covering of dust. It was steering the ball with its back legs, while it scrabbled for purchase with its horny front legs. Progress was unthinkably difficult as the ground was rough, and, of course, it was quite unable to see where it was going, head down, facing away from the desired

direction

of travel, with a huge ball of shit in the way. The ball kept going out of control and rolling over the poor creature, yet without so much as a moment to dust itself down, the beetle picked itself up and patiently resumed rolling on its intended course. Chloë and I marvelled at its dogged persistence, and felt sorry for it, and tried to suppress our giggles when the dung ball rolled over it time and again.

Now the presence of a dung beetle in our valley is a matter of some symbolic importance, being a direct result of our policy not to worm the sheep more than absolutely necessary. The sheep are fine; they have a few intestinal parasites – all such organisms do – but they live with them in a reasonably harmonious symbiotic state and as a result produce dung that’s safe enough for the humble beetle to deposit its eggs in.

I know about this because I once had the privilege of chatting with a world expert on dung beetles – Jan Krikken, a Dutch entomologist whom I happened to bump into one afternoon in the valley while he was staying in our

neighbour’s

cottage. He had been creeping along on all fours by the edge of our

acequia,

the irrigation channel, stopping from time to time to suck on his pooter – a strange device like a jamjar with two tubes sticking out of it, one with gauze at the end which you put in your mouth, and the other an open tube which you place above an insect under study. By giving the first a spirited suck, the specimen is whooshed painlessly and undamaged (if a little surprised) into the jamjar to be examined at leisure. Suck on the second, however, and the surprise is all yours.

Dr Krikken had been employed some years earlier by the Australian government to reintroduce dung beetles after decades of excessive sheep worming had all but eradicated them. There was a fear that without the beetles’ help in

rolling

and burying the dung, it would fail to decompose and the continent would become caked in a mat of excrement. Fortunately, he had been able to save the Antipodeans from this fate. ‘If you ever doubt the importance of organic

farming

,’ he suggested to me, ‘just spend some time looking at dung beetles.’

It seemed good advice, and I follow it as often as I can – and, indeed, here I was, head down and deep in

contemplation

. Yet, the longer I looked at our specimen, the more it seemed that something wasn’t quite right. I thought about it for a bit and then the full, astonishing truth dawned on me. ‘You know what, Chloë?’ I announced. ‘That ball is not a ball of dung at all. It’s a squash ball.’ I paused to let this dramatic revelation sink in.

‘What’s a squash ball?’ she asked.

‘Well, it’s a ball you play squash with.’

‘Yes, but what’s squash?’ she persisted, as any Spanish schoolgirl might.

‘It’s a game, where you hit a ball… with a racket… in a court… and it bounces off these three walls…’

It was at this point that I started to realise the utter fatuousness of my conjecture. The nearest squash court would probably be two hundred miles away in Marbella or Sotogrande. How, then, did a squash ball come to be rolling around in our valley propelled by a dung beetle? It made no sense. However, I’d got started on this tack now, and I wasn’t about to stop. I dug down deeper into my hole.

‘You see, Chloë,’ I continued, ‘this particular ball is just too perfect to be the work of a beetle. Look, it’s absolutely spherical and perfectly uniform in colour and texture. How is a creature as ungainly as that going to create a thing so perfect from a heap of sheep shit? You tell me that. It’s a rubber ball.’

Chloë looked closely at the beetle and its ball. ‘It’s dung, Dad. I’m sure it is. I know dung when I see it.’ ‘No, it’s a rubber ball, child. And the awful thing is that, when this poor benighted

bicho

gets its ball home, after all that terrible effort, it’s going to find that it’s made of rubber

and not dung, so it will neither be able to form it into a pear shape, scoop out a hollow and lay its eggs in it, which is what they do, nor eat it. It’s going to break its little heart.’

‘It’ll be alright, Dad. It’s dung, really,’ Chloë reassured me. ‘It’s not what you think it is. Its little heart will be fine.’

I had to differ. ‘No, Chloë, I know I’m right and I’m not just going to sit here and watch the poor thing being deceived like this. I’m going to take its ball away. At least then it will still have the time and energy to make itself a proper ball and get the job finished.’

Chloë was appalled. ‘Don’t do that, you can’t do that. The poor thing will be devastated if you take it.’

‘It’ll be a lot less so now than after all that futile effort of rolling the cussed thing home,’ I insisted.

‘Dad – don’t!’ cried Chloë, as I crouched down next to the insect and its ball.

But I, with my fifty years of experience of the world, was adamant. I reached out a hand to pick up the dusty squash ball… and my fingers sank into the soft dung.

‘Oh God, it is dung.’

‘I told you so. Now look what you’ve done! You’ve gone and ruined it.’

I looked at the once-perfect dung ball. It was split right open, the moist dung in the centre temptingly displayed. It looked like one of those delicious chocolate-dusted truffles, with a moist greenish filling. I tried to mould it back to its earlier shape, to emulate the beetle’s perfect craftsmanship, but to no avail.

‘Put it back, Dad. You’re only making it worse.’

I was filled with a terrible remorse. The tiny creature looked up at me disconsolately from way down on the

ground. Chloë stared at me as if I were some sort of

half-wit

.

Gingerly I returned the squidged mound of dung to the beetle and straightened up. There was an awkward silence.

‘Why?’ I asked, falling back on a little wordplay to try and defuse the tension. ‘Why is a beetle called

escarabajo

in Spanish?’

‘What do you mean?’

‘Why is an

escarabajo

called

escarabajo?’

‘I don’t know. I thought “scarab” was a really old name for beetles. Why do you ask?’

‘Because it’s es

cara bajo

– it’s face down.’

My daughter considered me thoughtfully for a moment, shook her head and set off up the hill to the house, no doubt to tell her mother.