The Alpha Masters: Unlocking the Genius of the World's Top Hedge Funds (23 page)

Read The Alpha Masters: Unlocking the Genius of the World's Top Hedge Funds Online

Authors: Maneet Ahuja

Ackman still sees the Rockefeller Center deal as one of the most significant investments of his entire career. He spent many months analyzing the company, and the more he studied it, the more he admired what he calls the “brilliant” structure of the company. In the mid-1980s, the Rockefeller family wanted to take out a $1 billion-plus mortgage loan on the property, but there wasn’t a bank big enough to lend it to them. Instead, they set up a public company structured as a real estate investment trust (REIT) called Rockefeller Center Properties. That company then made a $1.3 billion mortgage on Rockefeller Center, with the mortgage the public company’s only asset.

The public company was complicated; it was financed with debt and equity. The mortgage was a participating, convertible mortgage with many additional fancy features to it. David Rockefeller was chairman of the board, and investors bought the stock largely because it paid a big dividend and they liked the idea of partnering with the Rockefellers. As the real estate market was falling apart in the early 1990s, the company was forced to cut the dividend. The stock price collapsed, and the REIT was under a lot of financial stress due to its high debt load and its inability to roll over its short-term financing.

Rick Sopher, Chairman of LCH Investments NV, the world’s oldest fund of funds recalls: “I was introduced to Bill in 1995 as I had been doing some work at Edmond de Rothschild Securities on the Rockefeller Center situation and hoped Bill might buy a few bonds through me. But I was overwhelmed by the energy with which he tore into this terribly messy situation; how he came back within days having done more research than I had ever imagined was feasible. He had literally paced out the buildings, scrutinized the leases and uncovered all manner of really complex issues which even the company had yet to fully appreciate. Later on, I was struck by his hunger and imagination; whereas a normal investor might have settled for buying a few undervalued bonds, Bill, even at that age, was staggeringly brave and ambitious, coming up with far more lucrative plans. I suppose that encounter with Bill in 1995 was one of reasons I became so enthusiastic about investing with external managers of this type.”

Ackman cleverly figured out that by buying the stock in Rockefeller Center Properties on the stock exchange, you could create an interest in Rockefeller Center at a very low price. “And if you could foreclose on that mortgage, you could own Rockefeller Center for a fraction of its long-term value. In addition to six million square feet of office space, it included some of the most valuable yet undermanaged retail space in the world, two million square feet of air rights, Radio City Music Hall which was rented for one dollar a year, and more,” says Ackman one cold January morning at his forty-second floor offices at 888 Seventh Avenue. Snow fell below as Ackman looked out on the afternoon New York City skyline from his office. He had a gleam in his eyes and seemed to get excited again just thinking about his long-ago plan.

“So I ran around town trying to convince another investor to partner with us so we could buy the whole company and own Rockefeller Center,” Ackman recounts. But no one seemed interested or understood what he was talking about. “I spoke to the smartest real estate investors I could find including Richard Rainwater and Steve Roth,” he says. Then his dad told him to call Joe Steinberg, President of Leucadia National Corporation, a publicly traded investment holding company. Steinberg agreed to meet, and their half-hour meeting turned into four hours of going through the deal. Ultimately, they ended up partnering on Rockefeller Center, and Leucadia bought a big stake alongside Ackman in the company. This was Ackman’s first high-profile active investment and the beginnings of an important relationship with Leucadia, with whom he would partner on many future deals including a $50 million investment from Leucadia that would help launch Pershing Square about 10 years later.

Ackman’s proposal to take ownership of Rock Center called for a recapitalization of the REIT through a $150 million rights offering backed by Gotham and Leucadia. The board turned down Ackman’s and Leucadia’s proposal, opting for a deal with a white-shoe group which included David Rockefeller, Tishman-Speyer Properties Inc. and the Whitehall Street Real Estate LP, a real estate investment fund managed by Goldman, Sachs & Company, who on October 1, 1995, offered to pay $296.5 million, or $7.75 a share, for the company. The investor group at the time would also assume about $800 million of the real estate investment trust’s debt, about $191 million of which was owed to Whitehall and a Goldman Sachs subsidiary.

Before the Goldman deal closed, Ackman received a call from Donald Trump who said that Goldman Sachs was trying to steal Rockefeller Center. “We have to do something about it,” said Trump. “I’ll come by your office.” Embarrassed by his sparse surroundings, Ackman quickly offered to hop a cab to Trump Towers instead. Trump’s idea was to convert 30 Rock into a residential condominium, but the tower had been nearly fully leased for many years into the future to multiple tenants, making the strategy unfeasible.

In July 1996, Goldman Sachs, Tishman-Speyer, the Agnellis, and David Rockefeller were awarded the deal and took control of the complex for $1.2 billion in cash and assumed debt. Gotham made a tidy profit on its investment in the REIT.

Though he didn’t end up owning the property, Ackman values the experience and relationships he made during the course of the investment. After the deal closed, Leucadia sent Ackman a check for a half a million dollars and four Concorde tickets to Paris.

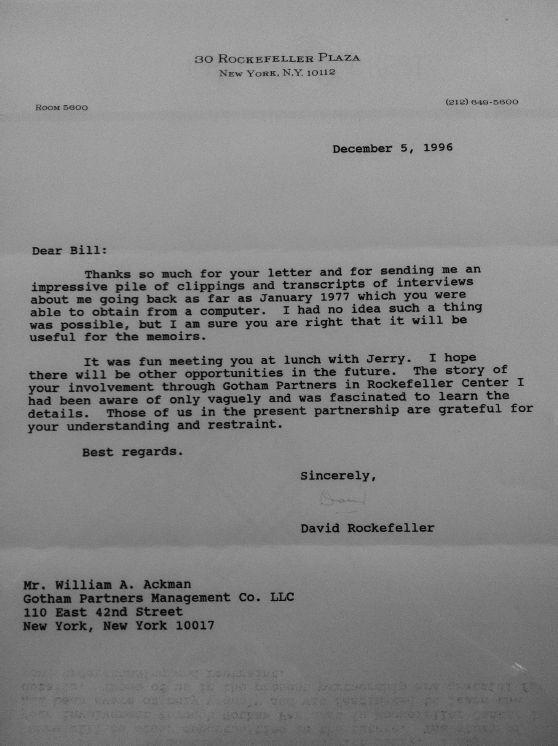

Steinberg has gone on to do many deals with Ackman, and the two have become good friends who get together for boys-only scuba diving trips off the coasts of exotic islands. The experience also earned Ackman a letter from David Rockefeller and an invitation to lunch at the Four Seasons with Rockefeller and Jerry Speyer. In the letter, Rockefeller thanked Ackman for his restraint in not using his large shareholding to block their deal. Ackman still keeps the framed letter on his desk.

Despite the monumental experience, the deal still haunts him. “For years,” Ackman recalls, “I couldn’t walk by Rockefeller Center without getting butterflies in my stomach reminding me that I missed out on one of the greatest investments of all time,” he says. But he learned from the experience. “It taught me that you can make a lot of money as an equity investor in a near-bankruptcy,” he says. It would be a lesson he’d end up using to make the best investment of his career.

Making a Name for Himself

By 1998, five years after opening up shop, Gotham Partners had grown from $3 million under management to over $500 million. After the Rockefeller Center deal had closed, Ackman walked away with some powerful players on his side. Vornado’s Steve Roth told Ackman that to call him next time he had a good idea. According to public sources, Gotham attracted prominent, well-respected investors as its limited partners. Hedge fund legend Jack Nash gave Ackman $1 million to invest. Years later when Nash shut his fund, many of Nash’s investors turned to Gotham. Even David Rockefeller invested.

Return on Invested Brain Damage

Ackman’s first proxy contest for control of the board of First Union Real Estate did not end up being a good investment but was an important experience. Ackman credits the investment for helping him create his “return on invested brain damage calculation,” which taught him to consider time and energy required in the calculation of whether an investment made sense

On July 14, 1997, Gotham sent a letter to First Union’s board of directors voicing his concerns about the direction of the company and asking for a meeting with the board of trustees. Ackman had been building up a stake over the past year and was not happy about the current state of the company. But after many requests, First Union still refused to meet. “First Union was a paired-share REIT,” explains Ackman. “This was a company with a grandfathered corporate structure. It was a REIT ‘stapled to’ a ‘C-corporation,’” a traditional corporation that could own any kind of business. So when you bought stock in the company, you actually were buying interests in two companies. The structure enabled First Union to own real estate–intensive operating businesses that could not normally be held by REITs, thereby minimizing their corporate taxes. Since there were only four such paired-share REITS in existence, Ackman believed that the company’s unique structure made it worth well more than the value of its real estate assets.

So Gotham solicited proxies to replace all but three of First Union’s trustees up for election at the May 19, 1998, meeting, putting up Gotham nominees Ackman and David Berkowitz and seven other directors, including James Williams, chairman of Michigan National Bank, and Mary Ann Tighe, a highly successful leasing broker from New York. When Gotham got on the board of First Union, “it was a mess,” says Ackman. The previous board, in a scorched earth strategy, had triggered a change in control under all of the company’s indebtedness, including $100 million of public bonds. “So we negotiated a deal with the company’s bank lenders and borrowed $90 million in a bridge loan from a group of shareholders, paid off public debt, did a rights offering to pay back the loan, and then brought in a new management team,” says Ackman, who became chairman after the successful proxy contest.

During the proxy contest, the company’s paired-share structure was severely restricted by a change in the tax law due to lobbying by the Marriott Corporation and other hotel companies who felt the paired-share structure was an unfair competitive advantage.

After the Gotham directors were voted in with a landslide victory, they controlled a company that had lost nearly all of the benefits of its paired-shared structure. It was highly leveraged, with nearly $300 million of recourse debt in default or puttable as a result of the prior board’s not approving the new directors. It also had a jumble of different B-minus or worse real estate assets. Without a viable alternative, the board elected to largely liquidate the company, selling assets to pay down debt until it was finally reduced to assets that could not be sold, a pile of cash, and some contingent liabilities that were difficult to value.

These unsalable assets and complex contingent liabilities, however, prevented the liquidation from being completed within a reasonable period of time. The company then hired an investment bank to solicit interest in First Union’s public listing and cash assets. While nearly 90 potential companies expressed interest in signing a confidentiality agreement and learning more, none came forth with a proposal to merge with the company.

The board then approached Ackman about merging with a golf company held by Gotham Partners. After months of negotiation with the board, which included representatives from Apollo, the private equity firm, and Cerberus, as well as Bruce Berkowitz, now the manager of the Fairholme Fund, in September 2001, the company announced a deal to merge Gotham Golf and First Union. In late 2002, that deal would founder when a New York judge issued a temporary restraining order, which would later be overturned on appeal more than nine months later in September 2003.

Buying the Farm

In mid-2002, Ackman made his first publicly disclosed short position in a company called Farmer Mac. Ackman used credit default swaps (CDSs), which were just gaining prominence, to express the short position. Ackman believed CDSs were a more attractive way to short a company given their limited downside and potential for asymmetric returns. He had started researching the Federal Agricultural Mortgage Corporation, or Farmer Mac, earlier that year after his close friend from college, Whitney Tilson, recommended that Ackman take a look at the stock as a potential long investment.

As he took a closer look at the company, which was chartered by the U.S. government to create a secondary market for farm loans, Ackman got more and more interested. The company relied extensively on short-term financing to fund its business, making its viability highly vulnerable to its ability to access the capital markets. Ackman had concerns about the quality of the company’s loan portfolio and its leverage ratios. Even though the company was unrated by the rating agencies, its debt traded like triple-A-rated bonds with a very tight spread to Treasuries, and this contributed to Bloomberg’s mistakenly reporting the company’s debt as triple-A rated, due to confusion in the marketplace about the company’s connection to the U.S. government.