The Amateurs (15 page)

Authors: David Halberstam

Tags: #Olympic Games, #Rowers - United States, #Reference, #Sports Psychology, #Rowing, #Sports & Recreation, #General, #United States, #Olympics, #Rowers, #Biography & Autobiography, #Essays, #Sports, #Athletes, #Water Sports, #Biography

In the final he intended to work off Tiff Wood. If Biglow could stay within a length of Tiff at the five-hundred mark, he was confident he could win.

Because the wind kept rising above acceptable levels, the officials had to delay the start of the final. Tiff Wood sat on the lakebank in his Saab, his fiancee and his family coming over to talk to him and then quickly departing. His mood did not encourage small talk. He seemed a part of this event and this party yet completely distant from it. There was too much time to think. Even fighting off tension was a sign that the tension was considerable. He liked, as much as any sculler could, the act of racing, but in the past he had been plagued by his own doubts. He was certain of his physical abilities and his willingness to pay whatever price the race demanded, but he was aware that before a race he often became too tight and constricted, too emotionally involved in what was yet to take place, for his own good. He envied John Biglow's confidence. Confidence it might not really be, but it

seemed

like confidence, and that was good enough. Biglow was going around the area where everyone was waiting, appearing hardly mindful of the event just ahead.

Only in 1983 had Wood been miraculously able to free himself from the tension that plagued him. That had been a wonderful year for him. Beaten by Biglow in 1981, Wood had rededicated himself to rowing in 1982, working hard for the first time on his technique. His major fault had been that, in rowing terms, he "shot his slide"—that is, he did not connect the drive of his legs and the drive of the rest of his body well, a failing that not only cost him power but also made the boat lurch. The hard work he poured into rowing in 1982 was beginning to show dividends near the latter part of the season, and he had been optimistic about the 1982 trials. Then, in the final in 1982, he had had to row on an appalling course in Camden, New Jersey. It was poorly marked, and he had hit several buoys in succession; he hit the last one hard and flipped. He had been in the process of saying "oh, shit" when he landed in the water. He had wanted the race rerowed, and the Olympic officials who were there had agreed, but the local people had been unwilling to do it. That had ended his hopes for 1982.

But the hard work he had put in had paid off the next year, when things that had never gone right suddenly started falling into place, both in his rowing and in his personal life. It was if he were touched, floating above himself. That feeling had carried right through from the American trials to the world championship at Duisburg in West Germany.

Pertti Karppinen, the great Finnish champion, was not rowing singles in 1983. Peter-Michael Kolbe of West Germany; Uwe Mund of East Germany; and Vassily Yakusha of the Soviet Union, the silver medalist from the Moscow Olympics, were favored to finish in that order. Looking at the field, Tiff Wood suddenly had a strong feeling that he could medal. He was there, he kept reminding himself, because he was

the best sculler in the United States of America.

He was already a champion; no one had a right to demand anything more of him. In that sense he was in the perfect position to do well; little was expected of him, and he felt immensely confident. In his heat against Kolbe, who was probably the second-best sculler in the world, Wood had rowed almost even, losing by one second. That had placed him in the repechage. He easily made the semifinal, and though he did not row particularly well in the semi, he still came in second to Mund, with Yakusha third. Wood had scrambled from the start, rowing clumsily and heavily, exerting far too much energy for the speed he was generating. Even so, he had beaten Yakusha. Kolbe and Mund might be a level above him, but they were within reach on the right day. Never had he felt so optimistic.

When the final started, Kolbe, Mund and Yakusha all went out quickly, far ahead of him. After the first hundred meters, he could not even see them. He felt an immediate disappointment and faulted himself for his foolish vanity. He would have to be content with simply rowing his own best race. It would not be the worst thing to come in fourth or fifth. At 250 meters he took a power ten to try to make even the smallest move on one of the three leading boats. It was a futile effort; they were all still out of sight. At that point, he had to fight against losing his desire and his mental toughness. The one thing that kept him going was a sense that he was rowing well. At the thousand-meter mark he still could not see the three leaders. Then, with five hundred meters to go, he looked and, miraculously, there was Yakusha very near him; the two of them were in a real race. If he had fallen that far back, Wood knew, Yakusha was in real trouble. So Wood poured it on, summoning every bit of energy he could, gaining not just on Yakusha but on Kolbe as well. The Soviet was burned. With barely fifty strokes left in the race, Wood heard the crowd; the roar was enormous and it was not for Kolbe. Rather it was a West German crowd cheering for an unheralded American who was going to beat a Soviet. With thirty strokes to go, Wood passed Yakusha. I'm going to get a medal, he thought, I'm going to get a world medal. Suddenly he panicked; and thinking he had made a mistake, he quickly counted the number of boats that had finished and the number still on the water. He had not miscounted; he was third. He was the bronze medalist. He had beaten the man who had been second in Moscow. It was for Wood a glorious and lasting moment, and he still found it remarkably easy to hear that West German crowd cheering him on.

A few weeks later he had rowed at Lake Casitas near Santa Barbara in a regatta that had been specially scheduled as a pre-Olympic tune-up so that American and foreign oarsmen and coaches could test the water there. Though Kolbe and Karppinen did not show, the field was fast—Ricardo Ibarra of Argentina, Svensson of Sweden, Mund of East Germany, Pat Walter of Canada and John Biglow. Wood had rowed very well in the final; Mund and Ibarra had gone out early on him, but he had rowed through Mund at 750 meters and then, with ease, through Ibarra at fifteen hundred meters, winning with energy to burn. Biglow had taken fourth. The race confirmed that Duisburg was not a fluke. But a few months later, both victories were something of a burden to Wood, for in 1984, all the American scullers were tracking him. As the favorite, he was everybody's target.

The crowd at Princeton was small, more like an expanded tailgate party than an Olympic qualifying event. Most of the hundred or so people watching the semifinals were other rowers, or friends or families of oarsmen. Some doubles races were also taking place, scheduled by Kris Korzeniowski, the sweep coach, as part of the sweep selection. John Biglow's present roommate, Fred Borchelt, was rowing in a pair, as was Steve Kiesling.

On the sidelines the families of several of the oarsmen were grouped, old friends now at a reunion. Anthony Bouscaren, Joe's father, congratulated Richard Wood, Tiff’s father, on how well Tiff had rowed this year, and John Biglow came over to talk with the fathers of his two chief adversaries. He knew Anthony Bouscaren very well, since Mr. Bouscaren had watched John almost as faithfully as he had watched his own son during their Yale years. Biglow had also, from more recent sculling championships, come to know Richard Wood; and he told Mr. Wood that his own father, Lucius Biglow, a passionate follower and photographer of his son's rowing activities, had taken some great shots of Mr. Wood and Tiff at last year's world finals. The fact that Mr. Biglow was not present at this race was taken by some of Biglow's competitors as a sign that John's back still was not completely healed; they were sure Mr. Biglow would not miss an Olympic trial if John was truly ready.

All of this managed to give the impression of an event from another time and another place as yet uninterrupted by change. It was probably the absence of television as much as anything that allowed the past to survive and remain so powerful. Since ABC was handling the Olympics, it was duty bound to include rowing. There had been talk about one of the scullers going on

Good Morning, America

to appear with a veteran sculler of the past, perhaps Dr. Benjamin Spock, but the people from

GMA

had wanted to tape the show in advance of the race. Dr. Spock, said Kathryn Reith, the young press officer from the U.S. Rowing Association, with a small measure of disdain, may have been a gold medalist, but he had rowed

sweeps,

not sculled in the 1924 Olympics. It was not, she said, the same sport. Well, said the

GMA

people, perhaps she could come up with an old-time sculler and the winner for the single sculls in time for their deadline. "We cannot," said Ms. Reith, "tell you the name of the winner, since we have not held the finals yet." The idea, not surprisingly, was soon abandoned.

Tiff Wood working out in a single

Joe Bouscaren starting a workout on the Charles

John Biglow before a practice

A pre-Olympic workout in a quad. Stroking: John Biglow, Paul Enquist, Brad Lewis and Tiff Wood

Henley 1977. Gregg Stone and Tiff Wood in a double

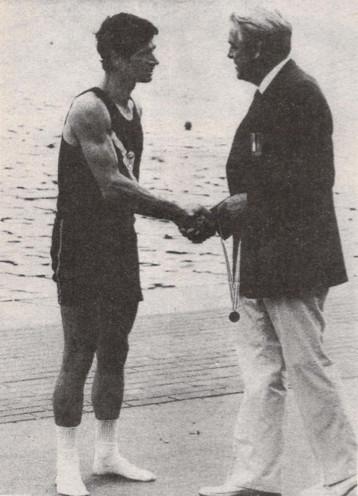

Tiff Wood getting a world bronze at Duisburg in 1983