The Ambitious Madame Bonaparte

Read The Ambitious Madame Bonaparte Online

Authors: Ruth Hull Chatlien

CONTENTS

Visiting a dying son—The seductive whirlpool of memory

Refugees from a revolution—An early loss—Snowball fights and arithmetic tests—Teasing Uncle Smith—Madame Lacomb’s school—Intriguing prophecy

The Belle of Baltimore—Dreaming of a brilliant match—Rumors about Napoleon—A Bonaparte in Baltimore—Their first encounter

A consummate flatterer—Quick wit and a sharp tongue—Aunt Nancy’s advice—The coquette and the guest of honor—“Destined never to part”

A shocking discovery—The wedding of friends—Passion awakes—Seeking a brother’s advice—A father’s worry and a daughter’s plea

The gregarious young Corsican—Lovers’ parting—Unsure of his intentions—Charade at a ball—Choosing her path

Lovers’ reunion—A headstrong declaration—Planning a wedding—A legal obstacle—Anonymous warning—A bitter break

Sent into exile—Arriving at Mount Warren—Confronting Mrs. Nicholas—Unsettling news—An “indecent” pronouncement—The return home

William’s plan—Betsy weighs her options—Patterson’s concerns—Reunion—A solemn promise—Christmas Eve wedding

A daring French wardrobe—Honeymoon in Washington—Scandalizing society—Dinner with President Jefferson—A ruinous deception

A plea for recognition—The great Gilbert Stuart—A needless contretemps—Defying the admiral—First news from Napoleon—Travel plans

Visiting the Du Ponts—A strangely pertinent play—Gossip at a ball—Assassination attempt—A letter from Paris

Orders for Jerome—Napoleon becomes emperor—Aboard a French frigate—Stalked by warships—An ominous decree—Betsy fears the worst

A diversionary journey—Sailing through hilly country—Unpleasant companions—A night of terror—The great falls

Pleading to Jerome’s mother—A false start—Back to Baltimore—Aboard the

Philadelphia—

Shipwreck!—British blockade—Betsy’s tender news

Winter in Baltimore—Two new friends—Conflicting reports—Patterson provides passage—Arrival in Lisbon—A romantic interlude—Jerome’s plan

Seeking refuge in Amsterdam—A warlike reception—Chased from port—Arriving in Dover—The object of curiosity

Visitors and propaganda—Robert brings news—The emperor’s rebuke —Hiding in a London hotel—Removal to Camberwell—Birth of a Bonaparte

Image of Napoleon—James Monroe’s advice—Jerome’s important mission —Betsy and Eliza quarrel—Secondhand news—Longing for home

A tearful reunion and a cold greeting—A distressing letter—Gloating critics—“Bonny Bonaparte boy”—Romance for Robert

Eliza’s big plans—Trapped in a cultural desert—Long-delayed letters—An unexpected shipment—A Patterson wedding

“My beloved wife…”—Rumors of European politics—“Filled with regret”—Another Patterson wedding—A mother’s vow—The emperor takes action

Betsy’s despair—Seeking news—Rebuffed by the ambassador—Dolley Madison’s kindness—“Prince Jerome”—An emissary—A crushing blow

A successful entreaty—Bitter reflections—Patterson’s proposal—Death of a namesake—His “only lawful wife”—An earnest admirer—Betsy’s plea

A flanking maneuver—Jerome makes a request—Betsy and her father join forces—James Monroe’s counsel—A surprising offer—Betsy replies

Fighting for her son’s future—The emperor responds—A fascinating diplomat—Bo is baptized—Betsy makes her choice

Firsthand news of court—Financial independence—Bo’s tutor—Renewed

joie de vivre—

A sister dies—Defending herself “with honor and spirit”

New ambassador, old nemesis—Bo’s tantrum—A house of her own—Mr. Madison’s War—Sending Bo to school—Protection from Jerome’s foolishness

News of a devastating defeat—A father’s sins—Debating Vice President Gerry—“Recent calamities”—A deathbed farewell

Disastrous news—An “important-sounding name”—War in the Chesapeake—The burning of Washington—Attack on Baltimore—Fears for a Bonaparte son

Death comes in threes—Birth of a “pretender”—Patterson’s expectations—Chaperons for the journey—Bo expresses fears—Overturned plans

Return to England—Finding congenial companions—A father’s harsh judgment—Paris, at last—Partaking of literary society—Fate’s cruel trick

Conflicting desires—Bo confronts his mother—Riding out a perilous economy—“An ordinary American boy”—A dangerous resemblance

Bo’s schooling in Geneva—Betsy’s highborn friends—A boy and his dog—Journey to Rome—The Princess Borghese and

Madame Mère—

Face to face

Affliction of the nervous system—Bo attends college—Betsy in Florence—An affectionate interlude with Jerome—Bo returns to America—A cruel deception

Reliving a grievous wound—A deathbed farewell—What might have been

Acknowledgements—Bibliography—Copyright Information—Reader Discussion Questions

FOR MICHAEL

THE FAMILIES

The Pattersons

William Patterson b. 11-1-1752

married Dorcas Spear b. 9-15-1761

William Jr. b. 3-21-1780

Robert b. 7-16-1781

John b. 3-24-1783

Elizabeth “Betsy” b. 2-6-1785

Joseph b. 12-6-1786

Edward b. 7-14-1789

Augusta Sophia b. 11-27-1791

Margaret b. 3-20-1793

George b. 8-19-1796

Caroline b. 6-30-1798

Henry b. 11-6-1800

Octavius b. 8-28-1802

Mary Ann Jeromia b. 10-3-1804

The Bonapartes

Carlo Bonaparte b. 3-27?-1746 / d. 2-24-1785

married Letizia Ramolino b. 8-24-1750

Joseph b. 1-7-1768

Napoleon b. 8-15-1769

Lucien b. 3-21-1775

Elisa b. 1-3-1777

Louis b. 9-2-1778

Pauline b. 10-20-1780

Caroline b. 3-25-1782

Jerome b. 11-15-1784

The Ambitious Madame Bonaparte

© Copyright 2013, Ruth Hull Chatlien

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission from the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations in critical articles and reviews. This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents either are products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or locales or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

eBook Edition ISBN 13: 978-1-937484-17-0

AMIKA PRESS

53 W Jackson Blvd 660 Chicago IL 60604

847 920 8084

Available for purchase on amikapress.com

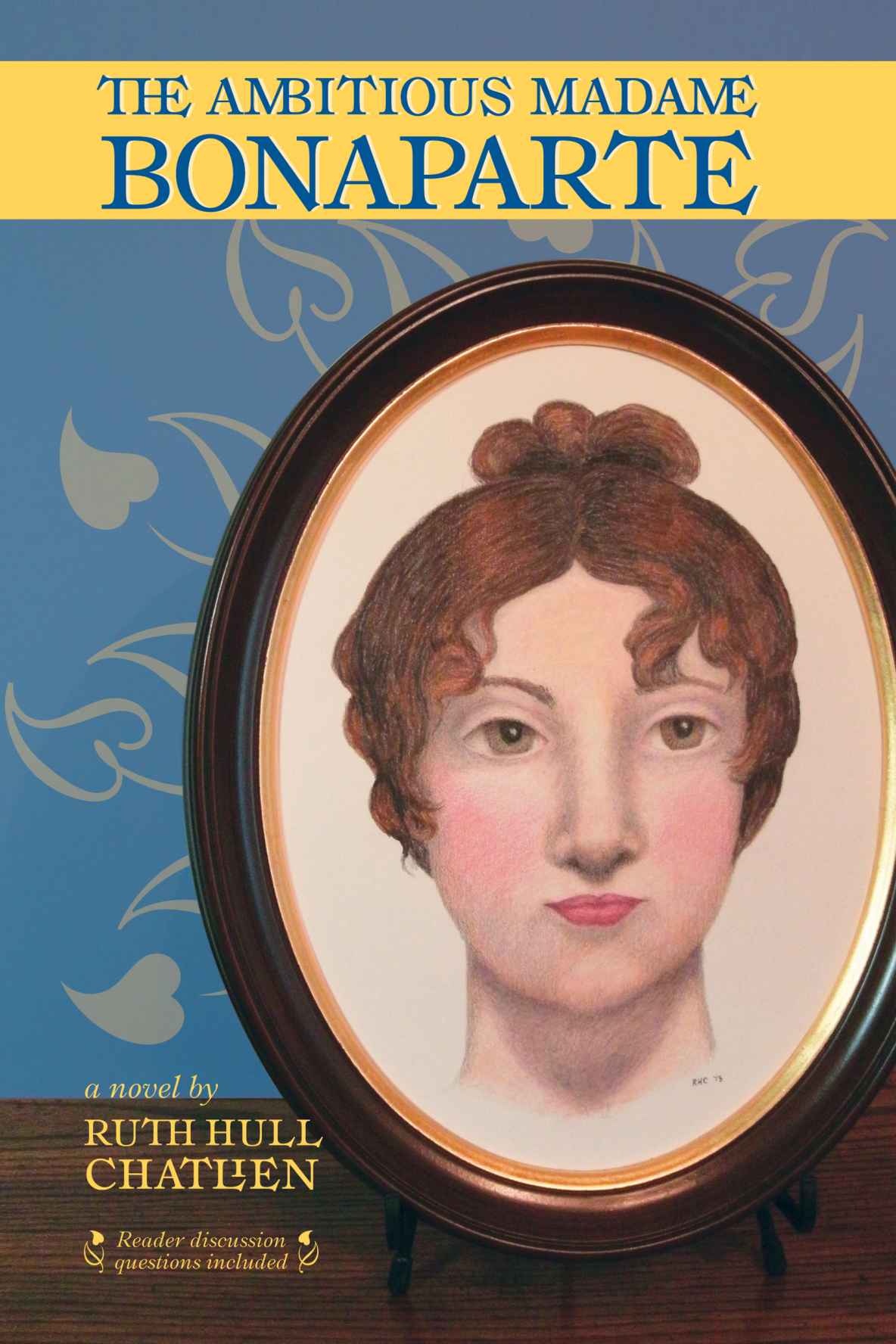

Edited by John Manos. Cover illustration by Ruth Hull Chatlien; framing by H. Marion Framing. Author photograph by Mike Krasowski. Designed & typeset by Sarah Koz. Thanks to Nathan Matteson.

PROLOGUE: JUNE 1870

T

AKING the footman’s hand, eighty-five-year-old Betsy Bonaparte gingerly alighted from the carriage and readjusted her voluminous skirts. How she hated the current bustled fashions, so much more cumbersome than the slim empire gowns of her youth.

As Betsy labored up the marble steps of her son’s mansion, her daughter-in-law opened the door. Susan May’s round face was lined with worry, and her dark eyes were sorrowful. She stepped back to allow Betsy to enter and then bent to kiss the tiny older woman’s cheek. “Mother Bonaparte.” Her tone was respectful but cool, which was all that Betsy expected. Their mutual antipathy was too long established to be overcome by shared anxiety for the man who linked them.

“How is Bo?” Betsy asked, using the family nickname for her son.

“No better. The doctor is upstairs now, so I am afraid you will have to wait a bit to see him. Maisie can serve you tea in the parlor.”

“No, thank you. I will wait in the Bonaparte room.”

Irritation flashed across Susan May’s face, but her demeanor remained polite. “As you prefer. I am sorry to desert you, but I must return upstairs.”

Betsy slowly crossed the hall to the reception room that Bo had turned into a museum dedicated to his Bonaparte heritage. Around the room’s perimeter, damask-upholstered chairs alternated with pedestals displaying marble busts of Bo’s paternal grandparents, Carlo and Letizia Bonaparte, and his uncle Napoleon. Against the red brocade wallpaper hung family portraits, including three of a younger Betsy.

Gazing at her favorite portrait, painted when she was a nineteen-year-old newlywed, Betsy remembered how her husband held her hand the whole time she posed. How happy she had been just to sit with Jerome, a contentment that lit up her face and enabled the painter to capture a supremely joyful expression. In Betsy’s opinion, it was the only portrait that had ever done justice to the classic beauty that once made her famous on two continents.

Betsy sighed for her lost youth. Then she crossed to the center table and picked up a miniature of her husband as a dashing young naval officer, wearing one of the braid-encrusted uniforms he had loved so much.

She closed her eyes and recalled standing at the railing of the French frigate

Didon

as it lay at anchor in New York’s upper harbor. Betsy had stared past other ships toward the strait they would take to reach the Atlantic. Somewhere out there, British warships were patrolling with the intent of capturing her husband. It was vital for her and Jerome to travel to France to obtain the emperor’s approval of their marriage, yet the prospect of waging a battle to break free terrified her. She and Jerome had already overcome so many obstacles just to wed.

As Betsy stood at the rail brooding, Jerome had called her name. She turned to see him approach her across the open deck. The sun picked out highlights in his curly black hair, and his face wore an expression of love and pride as he gazed at her. When he drew near, he said, “Captain Brouard wishes to see us. The pilot boat has returned from scouting the lower harbor.”

She laid a hand on his arm. “Is it bad news?”

He glanced swiftly around to make sure no crew members were near and kissed the top of her head. “I don’t know,

ma chérie,

but do not distress yourself. We will find a way to reach France, and when we arrive at Napoleon’s court, he will be delighted to welcome such a charming sister-in-law. Trust me.”

Betsy stared up into his dark eyes. “I do trust you, and I love you.”

“Then all will be well. With you at my side, I can accomplish anything.”

Betsy sighed again and wrenched herself free of the seductive whirlpool of memory. She ran her finger across the surface of the miniature as though she were caressing her late husband’s face. “Oh, Jerome. Our son is dying. How I wish I did not have to face this alone.”

I

E

IGHT-YEAR-OLD Betsy Patterson glanced up from her sampler and watched her mother lean back against her banister-back wooden chair and close her eyes against the mid-July heat. Even though the sashes of the two narrow front windows were raised, not a whiff of breeze found its way into the drawing room. The sheer white curtains sagged, as limp as wilted lettuce.

Normally at this time of year, the family would have retreated to Springfield, their country estate 30 miles west of Baltimore, to escape the risk of summer fevers. This year, however, Betsy’s father, William, thought it prudent to stay in town because of the Saint-Domingue crisis. For the past week, dozens of French merchant ships—mostly small double-masted schooners and brigs and single-masted sloops—had arrived in port carrying terrified people fleeing from the burning of Cape François. For years, the coffee and sugar plantations of the French colony had produced fabulous wealth, but now much of the island was a charred ruin because of a slave rebellion discussed only in whispers around children. Even though Betsy was not supposed to know about the troubles, she was proud because she had overheard that her father was one of the merchants donating funds to help the refugees.

Betsy believed it was only right that William Patterson should play a leading role in important events. After all, he was a friend of both Thomas Jefferson and President George Washington. Patterson had emigrated from Ireland in 1766 when he was fourteen. Later, during the Revolutionary War, he earned the beginnings of his fortune by running cargoes of gunpowder and weapons past the British blockade and supplying them to a Continental army on the verge of collapse. Now he was one of the wealthiest men in America. Given his worldly success, Betsy thought, he should be one of Baltimore’s most prominent citizens.

Betsy’s mother Dorcas was sitting by the side of the hearth, and Betsy glanced at the fireplace with approval. It was one of the finest features in the pale yellow room and demonstrated her family’s status without ostentation, something her father abhorred. The wooden mantel, painted dark teal, had fluted pilasters at each side and egg-and-dart molding running beneath the top shelf. Grey marble made up the surround. In the wingback chair on the opposite side of the fireplace, Betsy’s father sat reading his Bible, as he did every Sunday afternoon after dinner.

Betsy felt clammy with perspiration beneath her many layers of clothing. Taking advantage of her parents’ inattention, she stuck her needle into the linen stretched taut on the standing embroidery frame and committed the unladylike act of wiping her sweaty palms on her pink cotton skirt. She did not want to risk soiling her sampler. It displayed ten rows of text carefully embroidered in cross-stitch using red, blue, and green floss. The top six rows consisted of three different styles of alphabet, each running two lines. Beneath the alphabets ran a fancy border, and below that was a verse, which Betsy had chosen in defiance of the usual custom of using a pious motto:

We should manage fortune like our health,

enjoy it when it is good, be patient when it is bad,

and never resort to strong remedies but in an extremity.

The lines came from La Rochefoucauld’s

Maxims,

a book of sayings about human nature published in France in the 1600s. Betsy, who was halfway through memorizing all 504 maxims, loved to astonish adult visitors to her Baltimore home by reeling off a string of the mottos.

Currently, she was stitching the last word of the verse. All that remained to be done after that was the bottom line, which would read “Elizabeth Spear Patterson, Her Own Work. Anno Domini 1793.”

As Betsy bent to her embroidery again, two of her three older brothers bounded into the drawing room. Robert and John wore matching green cotton suits with long pants and loose jackets over open-collared, ruffled shirts. “Father, may we walk to the harbor?” twelve-year-old Robert asked. On the northern shore of the squarish tidal estuary of the Patapsco River their father had built his warehouse near the commercial wharves owned by their mother’s relatives, the Spears, Buchanans, and Smiths. The wharves were only four blocks from the Patterson home on South Street.

Patterson gave his two sons an appraising stare. “What business do you have at the waterfront on the Lord’s Day?”

“Josiah told us after church that more refugee ships are arriving.”

Patterson closed his Bible and set it on the marble-topped table next to his chair. “Son, we have had more than 30 shiploads of refugees. What is so compelling about these?”

John’s head drooped and he stepped backwards, but Robert said, “Sir, if we go on a Sunday, we will not get in the way of tradesmen.”

To Betsy’s surprise, their mother spoke up. “Let them get some air, Mr. Patterson. This is such a stifling day. Mayhap the breezes will be stirring by the water.”

“Mayhap.” Rising, Patterson smoothed down his coat. “I shall accompany them.”

Betsy stuck her needle in the sampler and stood. “May I come too?”

“No. Stay with your mother. Right now the harbor is no place for you.”

“But, sir, I have been there many times.”

“Elizabeth, you heard me.” After giving her a quelling look, he left the room with the boys.

With a flounce of her skirts, Betsy sat back on her stool but did not voice the complaint that screamed inside her head. Even so, Betsy’s mother sighed.

“You misapprehend his motives. The planters and merchants fleeing Saint-Domingue have witnessed terrible cruelties. Your father is only protecting you.”

“What kinds of things?” Betsy demanded, knowing that she could push her mother in ways her father would never tolerate.

“Child, you do not want to know.” Dorcas rose from her chair and went upstairs to check on her younger children, napping in the second-floor nursery.

THE NEXT MORNING as Betsy dressed, she saw Robert pass the nursery door on his way down to breakfast from his third-floor bedroom. “Bobby, wait!”

She dropped the shoe she was holding and hurried to the doorway. Robert, just steps behind William Jr., mumbled to their oldest brother and turned back.

“What was it like?” she whispered eagerly.

“What was what like?” Idly, he grabbed one of the leading strings customarily attached to the shoulders of little girls’ gowns and flipped it so it fell down Betsy’s back.

She glanced behind her and saw Mammy Sue buttoning the back of Gussie’s frock. “The refugee ship. Was it very horrible?”

“No, Goose. Just a shipload of miserable people who escaped the island with only the clothes they were wearing.”

“Mother said cruel things are happening on Saint-Domingue.”

Robert frowned. “Yes, but I did not see anything like that yesterday.”

“But you know about it. I can tell.” Betsy smiled in her most coaxing manner.

Robert shook his head and said quietly, “Father made me promise not to talk about it at home. He says that it is a man’s duty to shield women from ugliness.”

“Oh, fudge. You know that I have as stout a heart as you do. Johnny is the one who cries if we find a dead sparrow.”

Bending down, he gazed at her with a serious expression that reminded her of their father. “Both the blacks and whites are killing each other in unspeakable ways. The things Josiah said kept me wakeful all night. Do not ask me anymore.”

Betsy darted another glance at the family’s enslaved wet nurse and whispered, “Such a revolt could not happen here, could it?”

Robert shook his head, but his eyes still looked anxious. “No, Goose. Now go put your shoe on and I will tie the lace.”

ONE NIGHT IN November, the crying of the baby dragged Betsy from heavy sleep. “Mammy Sue?” she murmured and waited for a deep, calming voice to answer.

When no reply came, Betsy reluctantly opened her eyes. The chilly nursery was dark except for a glimmer of light around the edge of the door. That in itself was unusual. Betsy’s father was always the last person in the household to retire, and he not only made sure the outside doors were locked but also checked that the nursery door was tightly shut. Betsy strained her ears for the sound of Mammy Sue in the hall, but she could not hear anything except her sister’s bawling. Turning on her side and pulling the covers over her ears, Betsy felt surprised to find herself alone in the bed she shared with two-year-old Augusta Sophia. Then she remembered that Gussie was sleeping in their parents’ room next door because she was sick with a sore throat and strangling cough.

Baby Margaret wailed on, her tone building to outrage at being ignored. After another minute of ineffectually trying to block the noise, Betsy sat up, causing her bed to creak. Her little brother Joe whispered from across the room, “Do something, Betsy. Make her stop.”

With a sigh, Betsy flung off the bedclothes, stepped onto the cold wooden floor, and half hopped, half scurried to the cradle. As the oldest daughter, she was always the one who had to tend her siblings when Mother and Mammy Sue were too busy, and in a family of eight children, more problems occurred than the adults could handle: quarrels, scraped knees, runny noses, lost toys. Betsy envied her three older brothers, removed from the turmoil of the nursery—especially William Jr., who had a small bedroom of his own.

Someday when I am older, I will have a room to myself,

she thought as she slipped a practiced hand into the cradle to see if Margaret had wet herself. Finding the diaper dry, Betsy decided to carry the baby to her own bed.

As she placed a protective palm under Margaret’s head and carefully lifted the baby to her shoulder, she heard a muffled shriek followed by the sound of a door being flung open in the hall. Her mother shouted, “No! Leave her with me.”

Pulled by dread and irresistible curiosity, Betsy crept to the nursery door and opened it a few inches more. Instinctively, she put her thumb in Margaret’s mouth to give her something to suckle, and the baby quieted. Then Betsy looked into the hall.

Mammy Sue stood by the opposite wall holding a bundle wrapped in a sheet; she cradled it as if it were Margaret, while Betsy’s mother wept and clutched the wet nurse’s arm. Dorcas’s beautiful face was pinched and white. Betsy had never seen her mother in such disarray; her wrapper was unfastened, and her light reddish hair hung tangled on her shoulders.

Patterson stepped from the master bedroom and gripped his wife’s shoulders. “That is enough. You must not question God’s will.”

“God’s will?” Dorcas pawed the bundle in Mammy Sue’s arms. “How can it be God’s will to take my pretty girl?”

Betsy gasped. Then she squeezed the increasingly heavy Margaret as she fixed her gaze on the sheet-wrapped figure. Her father said, “Do not commit blasphemy, Dorcas. You know that such ills are the result of man’s sin, not from any evil in the divine nature.”

Betsy’s mother slumped and hid her face against his chest. Stroking his wife’s hair, Patterson made a shushing sound. “Remember that our Lord said, ‘Suffer the little children to come unto me.’ Gussie is with Him now.”

As he led Dorcas back into their room, he nodded at Mammy Sue. Betsy saw the slave begin to come her way, so she stepped back into the darkness of the nursery. She did not want the adults to know she had witnessed the scene.

FOR THE NEXT few months, Betsy found herself remembering Gussie’s dimpled face at odd moments and wishing she could feel her sister’s arms around her neck. She kept those feelings to herself, however, because her mother remained too sad to discuss Augusta Sophia’s death. Gradually, as baby Margaret began to display her own personality, Betsy stopped thinking of the sister she had lost.

In late February, two weeks after Betsy’s ninth birthday, a blizzard struck Baltimore. The sight of thick-falling snow outside the front windows proved to be too much for Betsy to resist, especially since her mother was talking to the housekeeper in the back building, which housed the kitchen, pantry, and servants’ quarters. Betsy hurried into the front entryway, donned her cardinal-red winter cloak, pulled up the lined hood, and crept outside.

When her father first came to Baltimore as a wealthy trader in 1778, he built three-story, red brick houses side-by-side on South Street, one to serve as his residence and the other as his place of business. Each had a front building approximately thirty feet wide and fifty feet deep, connected by a passage to a narrower back building that was not visible from the street. Because of the way the façades were constructed, the two buildings looked like one very wide mansion with two center doors beneath a classical portico. The first floor was raised slightly above street level, so a stoop of five steps—made of the local white marble so characteristic of Baltimore—climbed to the entrance. Betsy crouched by the side of those steps, concealed from her brothers as they returned home from school. As she waited, she formed a snowball and packed it tightly.

Soon she heard the shouts of boys coming toward her. She lifted her head just enough to peer through the iron railing at the side of the stoop and saw Robert approaching the counting house next door.

Rushing from her hiding place, Betsy flung the snowball, which missed her brother widely. He spotted her and shouted, “You little minx!”

Betsy shrieked as an unexpected snowball hit her left ear. Her hood had fallen back, so icy snow slithered down her neck. She whirled in the direction of the missile and saw Johnny slip in the snow as he ran, while William Jr. stood yelling for them to stop.

All four children fell silent as their father opened the black-painted door of his counting house. “Boys! Come inside.” Patterson stepped backwards. “You too, Betsy.”

He led them into the large front room where his clerks sat on stools before high slant-top desks, and the dusty ledger books of years past lined the shelves above their heads. Patterson set the boys to doing their daily bookkeeping exercises under the supervision of his senior clerk. Then he motioned for Betsy to follow him into his private office, which was furnished with a glass-fronted bookcase and a wide Sheraton writing desk that had raised cubbyholes along either side edge. A pair of framed etchings of company ships hung above the plain brick fireplace.