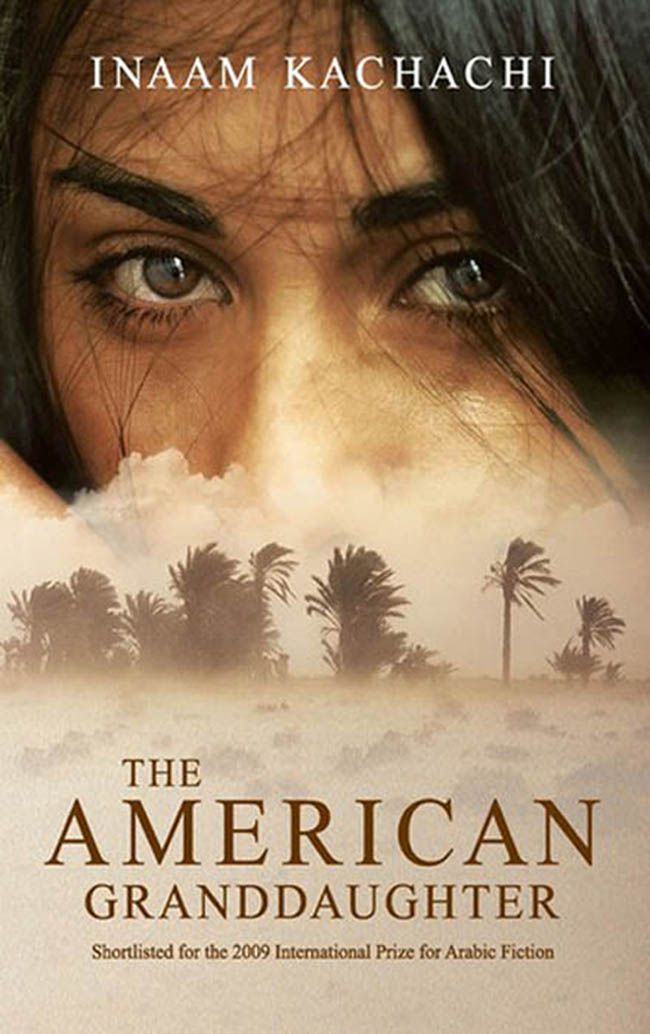

The American Granddaughter

Read The American Granddaughter Online

Authors: Inaam Kachachi

T

he

A

merican

G

randdaughter

Inaam Kachachi

Translated by Nariman Youssef

For Talal

Beware the beautiful woman of dubious descent.

An unauthenticated Hadith

Contents

If sorrow were a man I would not kill him. I would pray for his long life.

For it has honed me and smoothed over the edges of my reckless nature.

It has turned the world and everything in it a strange colour with unfamiliar hues that my words stutter to describe and my eyes fail to register.

Maybe I was colour-blind before. Or was my eyesight perfect then, and is the colour that I now see the wrong one?

Even my laughter has changed. I no longer laugh from the depths of my heart like I used to, unashamedly showing the crooked line of my lower teeth that Calvin once likened to a popular café in the wake of a brawl. Calvin meant to be flirty that day. But flirting no longer suits me now. Who would flirt with a woman who bears a cemetery inside her chest?

Miserable, that’s what I’ve become. A dressing table turned upside down, its mirror cracked. I laugh joylessly from the outer shell of my heart. A fat-free laugh, low-cal, like a tasteless fizzy drink. I don’t even really laugh, but just struggle for the briefest smile. It’s as if I have to repress any possible joys or fleeting delights. I have to keep my inner feelings well covered for fear they’ll boil over and reveal the state I’ve been in since Baghdad. I came back feeling like a squeezed rag, one that we use to mop the floor.

A floor cloth. That’s how I returned.

I have left behind many of the habits I’ve had since childhood. I no longer look at what happens around me as a sequence of raw footage, every chapter of my life a movie tempting me to find a suitable title. Now my hardest-hitting movie is running before my very eyes and I can’t find a title that would possibly fit. I see myself on the screen, a disillusioned saint carrying her belongings in a khaki backpack, wearing a hard helmet and dusty boots and walking behind soldiers who raise the victory sign despite their defeat. Where have I come across this scene before? Was it not also there in Iraq, in a past age, in another life? Are defeated armies bred on the fertile land between those two rivers?

I confess that I returned defeated, laden with the gravel of sorrow and two sweet limes that I craved on my mother’s behalf. My mother, who it seems discovered the saving grace of disappointment long before I did, particularly on that day in Detroit when she pledged allegiance to the United States and attained the boon of its citizenship.

Her eyes welled with tears when I presented her with the green fruit picked from the garden of the big house in which she spent her youth. She took the limes in both hands and inhaled deeply like she was smelling her father’s prayer beads and her mother’s milk and her past life. A betrayed life encapsulated in two limes.

Yet, I like this sorrow of mine. I feel the softness of its gravel as I wade with bared soul into its fountain, and I have no desire to shake off its burden. My beautiful sorrow, which makes me feel that I am no longer an ordinary American but a woman from a faraway and ancient place, her hand clutching the burning coal of a story like no other.

Dil dil dilani,

To Baashika and Bahzani.

Baba went to the old town stall,

Brought us chickpeas and raisins.

He gave them to our nanny

And she ate them all . . .

My grandmother rahma rocks me back and forth, after settling me on her warm lap with my face towards her. My fragile chest meets her bounteous breasts. They spill out of her white cotton bra, which she boils in water and grated soap whenever it turns yellow with sweat. I look at her, spellbound by the pale rosiness of her face, and cling to her arms. My legs dangle on either side of her, not reaching the sofa on which she’s sitting with her knees elegantly touching, in the way she learned from

Eve

magazine. My educated grandmother, who could read and write and follow the press, who seemed a marvel among women of her generation.

She leans forward with me until the world starts to spin in my eyes, then she snatches me back, repeating all the while the old rhymes that engraved their message forever upon my still-soft memory. Rhymes inherited from the days of Mosul and the old stone house that sits on a cliff overlooking the river. The house of Girgis Saour, my great-grandfather whose surname Saour – the churchwarden – he acquired from taking care of Al-Tahira Church, together with its saints’ icons and its candlesticks that every Saturday had to be cleaned of the wax that had hardened on the shafts and polished with a slice of lemon.

They took me to Mosul one day when I was little. It was the Easter holidays, early April, and the valleys were ablaze with camomile flowers. The sprawling yellow vastness bewitched me, the scent of nature made me dizzy. The wild poppies growing out of the cracks in the rocks were an astonishing sight, as red as the cheeks of my cousins when they walked out of the bathroom with water dripping from their long hair. How could I not love Mosul, when everyone there spoke with my grandmother’s accent?

I liked my Mosul relatives, with their shiny backcombed hair and pale rosy faces. They would visit us at Christmas or when they came down to Baghdad to attend to business at a government office or to see a good doctor. They sat silent and worried on the edge of the wooden Thonet-style chairs that were common at the time. They sat as if ever ready to stand up, be it to receive a tea tray, welcome a new arrival or give the seat up to an elder, supporting small paunches with the right hand and running through the beads of a rosary with the left. When they spoke it was as if the kitchen cupboards had collapsed and a cacophony of pots and pans were spilling out. Words rolled out of my relatives’ mouths in a burst of

qafs

and

gheins

, with the elongated

alef

at the end making everything sound like the finale of a musical

mawwal

.

Ammaaa

. . .

Khalaaa

. . . They sounded like they had just stepped out of a period drama in classical Arabic extolling the chivalry of Seif Al-Dawla. Even though I loved my Mosul relatives, I never felt fully at home in that big humid house with the stairs that led up to more than one attic and down to several cellars. The steps were too big for my short skinny legs, and the single skylight at the top of the staircase wasn’t enough to banish the darkness.

My grandmother’s lullaby came back to me as I rode in the convoy along the road from Mosul to its surrounding villages. In Baashika the girls stood in front of their houses adjusting the white scarves on their heads as they watched us pass by. My movie about them would be called

Doves and Handkerchiefs

. The blank expressions on their faces gave nothing away. None of them were smiling or waving their handkerchiefs like in the scenes in my head from American World War II movies of girls in Paris and Naples waving to US Army convoys and climbing onto the armoured vehicles to steal a kiss from the lips of a handsomely tanned soldier.

I told the guys that Baashika was probably an old corruption of ‘

beit al-ashika

’, the lover’s house, while Bahzani, the neighbouring village, derived from ‘

beit al-hazina

’, the sad woman’s house. They applauded these pieces of trivia, but quickly returned to their mood of anxiety as we passed men with thick moustaches, dressed in white with bright scarves, who stepped out from behind the cypresses and threw fiery looks in the direction of our convoy. I wanted to jump off the truck, shout something like ‘

Allah yusa’edhum

!’ and make small talk with them. Maybe ask about the wheat season or about the nearest store to buy a loofah for the bath, or simply invite myself in for a glass of cold water in one of their houses. I wanted to flaunt my kinship in front of them, show them that I was a daughter of the same part of the country, that I spoke their language with the same accent, I wanted to tell them that Colonel Youssef Fatouhy, assistant to the chief of army recruitment in Mosul in the 1940s, was my grandfather. But all that would have been against orders, unnecessary chatter that could endanger me and my colleagues. Orders demanded I be mute. And so, for the first time, I resented my army uniform that was cutting me off from my people. It made me feel we were crouching in opposing trenches. We

were

in fact crouching in opposing trenches. Like any skilled actor, I felt I had the ability to adopt a role and change character, to be simultaneously their daughter and their enemy, while they could be my kin as well as my enemy.

From that day on, I became aware of the malady of grief that afflicted me, to which I adapted and for which I sought no cure.

For how do I fight a malady that brought about my

rebirth,

that fed me and let me grow

and rocked me to sleep,

that honed and educated me,

and disciplined me so well?

‘Ninety-seven thousand dollars a year. All expenses paid.’ That was the mantra that started it all. It spread among Iraqis and other Arabs in Detroit, setting suns alight underneath heavy quilts and making palm leaves sway above the snow that still covered front yards.

Sahira came over, tossed the words like a burning coal into my hands and left in a hurry without drinking her coffee. I heard the wheels of her old Toyota screech as she sped away to carry the good tidings to the rest of her friends and relatives.

This wasn’t the kind of thing you could chat about on your mobile. A national lottery to be won only by the most fortunate Arabic-speaking Americans like me and Sahira, who, when I asked her how she could go and leave her two teenage sons, simply said, ‘The boys? They didn’t sleep a wink all night, they were so excited. They stayed in my bed and were begging me to hurry up and register my name before the opportunity gets lost to someone else.’ Ninety-seven thousand dollars was enough for children to drive their parents into the battlefield. Add to that 35 percent danger-money, a similar percentage for hardship and professional welfare, plus a little bit spare here and a little bit there, and the amount could reach one hundred and eighty-six thousand dollars a year. Enough to say goodbye for ever to the miserable neighbourhood of Seven Mile, enough to make a down payment on a grand house in the heart of leafy Southfield and purchase a brand new car. Enough also to send my brother Yazan, whose name was now Jason, to drug rehab, and then support him through college.