The Angry Planet (6 page)

Authors: John Keir Cross

The principle that I have just outlined is the real

secret of the success of the

Albatross

. It is so designed that there are

two fuels in operation:

one to give the initial start-off, and a second to

provide the tremendous acceleration required before launching into space

itself.

It is this second fuel that is my own patent—it is this

that I regard as the keynote of my whole invention. The first fuel is, I can

say frankly, a highly concentrated essence of acetylene gas. The second fuel I

cannot in any detail describe, without becoming outrageously technical.

Briefly, it is an adaptation of atomic hydrogen—a method of making that most

dangerous of substances quite manageable.

It is capable of developing enormous power in a very

short space of time. And above all, it is light and easily packed, so that

enough can be stored and carried in the rocket for the return journey.

So much for the main problems of space flight,

overcome, as we have been able to demonstrate, in the

Albatross.

Minor

difficulties—such as that of providing a supply of breathable air for the

journey (a problem already solved in general by submarine designers)—were dealt

with as the ship was built. I will not here say anything about the innumerable

calculations it was necessary for me to make to be able to assure myself that

once the

Albatross

was traveling in space it would go in such a

direction as to fall into the gravitational pull of Mars. These are abstruse

things, not capable of being dealt with in a paper that has to conform to the

limitations Mr. MacFarlane has set on it!

There is only one picturesque detail I would like to

mention before closing this first brief essay, and that is that one problem

that worried me quite considerably for a time was: what if, during the

35,000,000 mile journey, we collided with a meteor? These are, as is well

known, very small—most of them are no bigger than golf balls, while some are

mere grains of dust. At the same time, although they are so tiny, there is no

doubt that because of their incredible velocity, they would go right through a space-ship

if there were a collision: and the kinetic energy released by the impact would,

more than probably, destroy the ship on the instant. For a time, as I say, I

was worried by this vision—what was the use, I argued, of expending endless

ingenuity in devising a rocket if it were going to be exploded by a pebble?

However, in the end, I realized that the whole thing was worth risking. Space

is so vast that in spite of the billions of meteors in it, the chances of a

direct hit on a space-ship (and I was able to prove it irrefutably by

mathematical calculation) are only one in

a million!

I feel that these few remarks conform to Mr.

MacFarlane’s requirements: namely, that I should write intelligibly for lay

readers, stating the general problems of space flight and how they were solved

in the

Albatross:

and, secondly, that I should be brief. I now—feeling

that this is barely more than an interlude (and one that, to my own mind, might

well have been dispensed with)—I now pass the pen to those more qualified than

I to continue with the actual narrative part of this book.

IV. A

JOURNEY

THROUGH SPACE, by Various

Hands

IMPRESSIONS OF

A

JOURNEY

THROUGH

SPACE,

BY VARIOUS

HANDS

I PREFACE this collection of short contributions and

fragments on what it felt like to travel through space, with a brief account of

how we found the children in what they called the “tooth-paste cupboard.” (It

is, as you will have gathered, Stephen MacFarlane writing again.)

The Doctor and I, expecting the sudden impression of

weight that would assail us on the start-off of the

Albatross,

lay down

on two highly-sprung mattresses we had prepared for the purpose just before the

Doctor touched the lever to launch the space-ship. We also wore masks,

specially designed by the Doctor, that pumped oxygen into our lungs

automatically. In these ways we hoped to overcome to an extent the

uncomfortable effects of the shock of leaving earth.

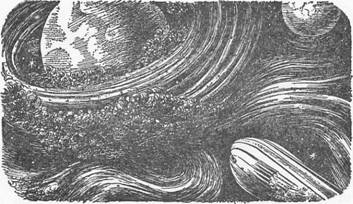

Nevertheless, my first feeling after seeing the Doctor

press the lever, was that someone had bound steel chains round my chest and was

constricting them, as it were, with a monstrous tourniquet. My head swam—there

were alternating flashes of colored light and darkness before my eyes. I felt

as if I weighed hundreds of pounds. I had hoped to be able to keep my gaze

fixed through one of the lower side windows of the

Albatross

, so that I

could see the earth receding from us. But I found this to be quite impossible.

When my sight did clear, and my head ceased pounding, all I could see below us

was a white swirling mist—a sort of milkiness—with, occasionally shining

through it, pale patches of indistinct green and blue.

The first feeling of heavy helplessness seemed to last

for at least half an hour; but, as it passed, I looked at the special clock

that was set into the instrument panel and saw that it had lasted barely one

and a half minutes. (Incidentally, I may say here in passing that because of

the complete weightlessness that affected everything in the rocket once we got

into outer space, this clock—although it had been specially designed by the

Doctor, as I say—absolutely refused to function: we had no real idea throughout

the journey what time it was—though, as you will see, we did manage to get a

notion whether it was day or night.)

We were well through the stratosphere and it was time

for the second fuel—the Doctor’s patent—to be set off.

I saw the Doctor rise from his mattress and, clinging

to one of the special hand-rails, creep along the instrument panel. He took off

his mask (we had started the oxygen apparatus before leaving, and the cabin was

full of good breathable air) and signaled me to do the same. I did so.

“I’m setting off the second fuel,” said the Doctor,

his voice sounding thin and distant in my ears, which were still buzzing a

little. “Better get into the foot-straps—or better still, put on the magnetic

boots.”

I nodded. The moment the second fuel was touched off

we would achieve a speed wildly beyond the speed of gravity. Everything in the

rocket would lose weight, ourselves included. To counteract this, the Doctor

had provided straps at strategic points on the floor of the cabin into which we

could slip our feet. He had also made several pairs of powerfully magnetized

boots so that we could walk about. The principle was very simple. As you tugged

at one foot in a walking movement, the slight jerk cut the magnetizing current and

so you could lift that foot and take a step. Then, when you put the foot down

again, contact was made in the sole inside by the muscular pressure, and the

magnet gripped the steel floor again. I now, as the Doctor adjusted his

controls, hastily put on a pair of these boots.

“Are you ready, Steve?” called the Doctor.

“All ready, Mac,” I replied.

He touched a switch. Immediately there was a powerful

shuddering all through the ship. And simultaneously there was, all through me,

an indescribably strange throbbing, and another attack of dizziness—but a

totally different kind of dizziness this time: an incredible sense of utter

lightness. I made to shout something to the Doctor, but my tongue seemed to be

waving freely in my mouth like a little fluttering flag and my lips were loose

and flaccid and quite uncontrollable. In a few seconds this attack lessened and

I was able to say something, although it was with the utmost difficulty at

first that I was able to articulate.

“Mac,” I cried, “this is incredible! This odd sort of

throbbing—I’ve never experienced a sensation like this before.”

“It’ll pass in a moment,” he called back. “You’ll soon

adjust yourself. It’s the heart—it’s been used to pumping blood all over you—a

considerable weight in blood: and now all of a sudden your blood doesn’t weigh

anything at all. Your poor old heart is just a little bit bewildered, that’s

all!”

He chuckled. He was in the highest spirits—it was

obvious that the

Albatross’s

performance was exceeding all his

expectations. He stood with his feet firmly dug into a pair of the floor-straps,

examining the scores of dials on the control panel.

“I’d hate to tell you the speed we’re traveling at,

Steve,” he cried. “Faster than any human beings have ever traveled before! In a

few hours we’ll be able to see the earth as a globe, man! Think of it—as a

globe!

”

I grinned at him. I caught the infection of his

enthusiasm. I raised my hand to wave at him cheerily, and then suddenly had to

burst out laughing. I had meant to raise it to my forehead in a sort of mock

salute—instead, without my being able to control it at all, it shot right up

above my head as far as it would go—and hung there, like something that was no

part of me at all, wavering slightly in the air. I hauled it down. For a moment

or two I stood there, practicing muscular control. I found that in a very short

time I could adjust my muscular exertions, so that I could move my completely

weightless fingers, arms, hands, and so on, in a reasonably normal way. By now

my head had cleared, and the throbbing of my heart had stopped—I felt fine:

elated, a little light-headed, as if I had just had a glass of champagne.

“Another few seconds and I shut off the motors,” said

the Doctor. “We have almost all the speed we need now, and we’re well clear of

the atmosphere. I say, Steve, could you go over and fetch me a pair of those

boots from the locker?”

I was just moving across the cabin when, all of a

sudden, and to our intense surprise, we heard the sound of hammering coming

from behind the door of one of our small store closets at the back of the

cabin. And, incredibly, there came to our ears very thin and muffled voices.

“Uncle Steve,” they called, “Uncle Steve! Let us out,

let us out!”

I stared at Mac and he stared at me. Even as I moved

clumsily across the cabin to the door in my magnetic boots, a horrible

suspicion was forming in my mind.

I had almost reached the door when it suddenly wafted

open (it was weightless, like everything else, and its movement can best be

described as like the movement in a slow motion film). And I had the strangest

surprise of my life.

Out of the open doorway floated—literally floated!—the

three children I had made such elaborate plans to dispose of to my cousin in

Glasgow! They were white and shaken—that much I could see as they drifted past

me. Their eyes had a dazed look. They moved their arms and legs in a stupid,

drunken sort of way. And all the time they floated and bounced about the cabin

like little balloons. For a moment one of them would rest on the floor or against

one of the walls—then, at a slight involuntary muscular movement, they would

shoot off at an angle and bump gently on the ceiling. They were yelling and

calling me to catch them and hold them. It was a grotesque, an idiotic sight!

“Good Lord!” I yelled. “Mike—Jacky—Paul!—what in the

name of all that’s wonderful are you doing here?”

“We didn’t mean it,” shouted Mike from the ceiling. “We

only came in to explore. We’d no idea you were going to—ouch!”

This exclamation came as he suddenly floated away from

the ceiling and collided with Paul, who was moving in a gentle glide diagonally

across the cabin. Jacky simultaneously drifted past me and I made a grab at

her. But the movement she made to grab at me in return sent her shooting off at

an angle, and next thing I saw she was right up in one of the corners of the

cabin looking as if she was about to burst into tears.

By this time Mac had recovered from his amazement at

seeing the children.

“Steve!” he cried, “for heaven’s sake get hold of them—do

something! They’ll smash up my instruments!”

He made a wild lunge at Paul, who was hovering just

over his head, and as he did so his feet came away from the floor-straps. And

he—Andrew McGillivray, Ph.D., F.R.S., of Aberdeen, Scotland—went soaring up to

join the human balloons in the air of the cabin! I alone of the party remained

on my feet. And, surveying the fantastic scene, I burst into laughter. It was,

undoubtedly, the funniest thing I have ever seen.

The Doctor was the first to get back to normal. He suddenly

cried: “The motor, Steve—shut it off! It’s past time—if we don’t stop it we’ll

develop too much speed, and we’ll use more of the fuel than we ought to, and

won’t have enough for the return flight.”