The Anybodies (5 page)

Authors: N. E. Bode

The Bone was quiet, letting Marty chatter. He kept his eyes on the road.

There was a lull in the conversation. Fern was thinking, trying to process everything she'd learned. The Bone piped up. “I just knew you were my daughter. I knew when I saw you.” His voice was soft for a moment, but he didn't let it stay that way. “Well, it was clear as a bell.”

“But how long have you been planning this? You didn't lay eyes on me until tonight!”

“Not true. Not true,” said the Bone. “Marty delivered a pizza to your house two weeks ago. And I'm the Good Humor Man you've seen. I hate that tinkling music. âHome, Home on the Range'âa million times a day.”

So that's why they had seemed a bit off. Fern didn't tell them that she'd been suspicious. They both seemed to have fragile egos about their Anybody abilities. But it seemed like those oddities in her life, those inexplicable happenings, might just have been real. “And Howard? What has Howard been?”

“I'm teaching Howard how to hypnotize other people, but he isn't old enough to do the transformations himself. Howard kept it running. He kept us on track. He had graphs and charts,” the Bone explained.

Fern was putting things together. “Which one of you was the man from the census bureau?”

“What?” the Bone asked. “What bureau?”

“Who?” asked Marty.

“Nothing,” Fern said. No, the man from the census bureau had been a bad force. She thought of the Miser and felt that old dread again. But just then something else crossed her mind. They were at a red light in the middle of town. Fern quickly took off her seat belt (the only thing that seemed to work in the car) and looked at the Bone's face. His eyes looked familiar. His chin seemed to jut out just so. Fern stared at him, and he stared back like he was going to ask her a questionâ¦a question aboutâ¦

her scissor kick

? Yes, her scissor kick! Fern gasped sharply, a yelp really, and flopped back in her seat. “Mrs. Lilliopole! My swim teacher!”

“In the flesh!” said the Bone proudly. “I would have preferred being a softball coach, but you were bent on swimming and there was an opening for a girls' swim coach at the YWCA. And the woman hiring was a real feminist, wanted to hire a woman. That was clear.”

“If you cut a Nerf football in half,” Marty explained, “and stuff each end into a swimsuit, it gives a pretty realistic look.” As a visual aid, he pulled two halves of a Nerf football out of his blouse the way Fern's science teacher used the plastic model human being with removable innards. “Back in our prime, of course, neither of us would have had to rely on such things.”

Fern couldn't shake the image of the census bureau

man and the dark cloud. She had to ask: “Could you ever turn yourself into, say, just for example, a bird, and then if a cat came along could you turn yourself into a dog or intoâI don't knowâa cloud?”

“Us?” the Bone asked. “Are you kidding? Maybe, just maybe, if our lives depended on it, we could have some great sparkling moment. But, knowing us, I doubt it even then.”

“You and me? Ha!” Marty said, shaking his head, almost laughing. “Nope. Once the Bone almost became a dog. He shrank to four short legs, grew fur even, but he couldn't get the tail or the muzzle. And it took three days to get even that far. Oh, well. Important thing is that we got him back. It took all of our concentration, mine and your mother's. He could have stayed that way, you know. Odder things have happened.”

“They have?” Fern had trouble believing that there were odder things than turning yourself into a dog and getting stuck that way.

“The Great Realdo could turn into a dog in three seconds,” the Bone said. “But you know what I mean, Fern. You've seen it happen, right? Remember the swimming pool?”

Fern didn't respond. She wasn't ready to admit to anything, not yet. You see, she was very well trained by now not to mention such things. She sat there, clamped down, eyes narrowed, as Drudger-like as possible. Something

loose in the car rattled, a few things actually. Fern held onto the door handle to see if the rattle would stop. One rattle did, but others jangled on.

“I have to say, Fern,” the Bone continued, “it was at the pool that things became clear. The bat? Remember?”

Fern stayed perfectly still.

“It wasn't planned. I don't know why it was there. But it was remarkable.”

It

was

remarkable

! Fern was thinking. She squirmed in her seat. She thought of the whistling kettle. Finally she blurted, “I saw it too. How it changed into a marble and rolled away!”

“I know you saw it,” the Bone said calmly.

“You do?”

“Yep. You denied it. That's what made it clear to me that you're mine. Any other kid would have been shocked, would have had a million questions about how a bat could become a marble. Any other kid wouldn't have been able to shrug and go on with their lesson as if nothing had happened, as if that kind of thingâ”

“Happens all the time,” Fern finished. “Well, not all the time, but often enough. And why is that?”

“You're being watched over,” the Bone said. “I don't know why.” He didn't dwell on it. But Fern wondered if it was the good kind of being watched over or the bad. “We had to figure a way to get you out. At least for a summer! I'm hoping you've got your mother's

head on your shoulders, just like you have her eyes.” The Bone said it, but then he blushed. “I don't mean anything by that! The eyes are nice enough. I didn't say they were beautiful or anything.”

But for the first time, Fern thought that someone actually meant that her eyes

were

beautiful. She felt shy all of a sudden. She sat back and buckled her seat belt again. She fiddled with the key that hung from the string around her neck. Fern wondered if the circus was in her blood, if she could be an Anybody, if she could turn other people into better versions of themselves. Could she turn the Drudgers into being something other than dull? She wanted to ask questions about the Miser, but didn't. There was one thing that needed to be very clear. Fern didn't want to ask, but she had to. “My mother is really dead?”

There was a pause. “Yes,” the Bone said.

Fern closed her eyes. Howard had been right. He hadn't fooled her. She missed her mother now, deeply, and it was strange because she'd never known her, had never known that she existed until just that evening. The missing was more painful than anything Fern had felt before. The image of her mother in the photograph holding her belly appeared in Fern's mind. It was all she had of her. “And the book?” Fern asked. “Her book,

The Art of Being Anybody

? Where is it now?”

Marty humphed and shook his head. “Funny thing,” he said. “No one knows. It was in their house before the Bone went to jail. But things were packed up after, well, after, you knowâ¦The bank came in and took everything out to sell. It could be anywhere, really, anywhere. Not that it would be of much use. It was written in a certain code only your mother could decipher.” The car got really quiet then. Even the windshield wiper froze as if holding its breath.

“Or you,” the Bone said.

“What?” Fern said.

Marty went on, “Now that we know about you, well, the idea is that maybe you'll be able to decode it. Your mother figured it out when she was your age, and then she could write that way. She even wrote coded grocery lists, sometimes out of habit.” He sighed. “The book has more secrets. Many, many more.”

“And we don't want the Miser to get his hands on it,” the Bone said.

“You needed me so you came and got me! That's the only reason! Because you think I'll be able to decode some book, some lost book!” Fern was angry now, more confused than ever.

“No, Fern,” the Bone said. “I came and got you because you're my daughter and, for better or for worse, you should know me.”

The rain was letting up. Fern could have told them

that she did have some powers. Hadn't she once gotten a book to cough up bunches and bunches of crickets? That wasn't exactly being an Anybody, but it was something, wasn't it? Hadn't she once turned snow into scraps of paper that asked her:

Things aren't always what they seem, are they?

Yes, she had, and it was true. Anyway, maybe it was nice to be needed, Fern thought, although she wasn't sure she could help at all. She gazed out the front windshield and noticed there was no rearview mirror. “Isn't it dangerous to drive without a rearview mirror?” she asked.

“I prefer to look into the future! I prefer to see what's coming. Why look back, Fern? In life, I mean. It's a waste of time. I never look back. Do I, Marty?”

Marty stared at the Bone but didn't answer.

The Bone squinted out onto the dark road. He seemed distant suddenly. He said, “I can still smell her lilac perfume. Your mother always smelled of the sweetest lilacs.”

THE BAD HYPNOTIST

THE BONE STOPPED IN FRONT OF A TRAILER IN

Twin Oaks Park to drop Marty off. Marty's wife was hunkered in the small metal doorway. She was a tall woman, so tall she had to stick her neck out, ducking her head down to fit in the small frame of the door. She was wearing a yellow bathrobe, tied too tightly at her middle, and pink spongy hair curlers. Her chin was set in a menacing scowl.

“By the way,” Marty said to the Bone. “You owe me money.”

“We weren't talking about money, were we?”

“No.”

“Then how can it be âby the way'? It can't be, can

it?” the Bone asked.

“I think it's an expression to say âby the way,'” Marty explained, a little defensive. “People say it all the time, even when something isn't âby the way.'”

“Yes, but it should be reserved for when something is âby the way.' Don't you think?” the Bone said, heatedly. “I mean, what would happen if there was no clear communication? We may as well all speak gibberish. Do you want us all to speak gibberish?”

Marty had to admit that no, he didn't want everyone speaking gibberish. And so, Fern noticed with a bit of pride, the whole issue of the Bone owing Marty money disappeared.

Marty looked at his wife. He mumbled, “Wish me luck,” and then he hopped out of the car. The Nerf football halves under one arm, he spread the other wide open and called to his wife. “What are you doing awake? You need your beauty sleep.” She didn't move; her glare only tightened on him. “Not that you

need

your beauty sleep. I mean, you're always beautiful⦔

“What's amatter with you?” Marty's wife started in. “I don't like that Bone character. I told you a hunnerd timesâ¦.”

The Bone hit the gas to drown her out. The car hesitated, coughed, then chugged off. Fern looked out of the back window. The trailer was lost in a cloud of exhaust. But as the exhaust thinned, the cloud took

on a smaller, tighter shape. In fact, the dark cloud followed, rolling alongside the car like a dirty tumbleweed. Fern refused to look at it. She tried to listen to the Bone, who was talking about his house. “Now, my place, the place I'm living in now, it's just a temporary dwelling. It isn't fancy. I don't go in for fancy. I like a roof over my head and plain living.” Fern rubbed her eyes and looked out the window again. The dark cloud was still there, though it was tripping along, sagging in on itself with exhaustion. “It's not like Tamed Hedge Road. It's not a house on a street like that. But it's nice enough.” She rubbed her eyes and looked again. The dark cloud was finally gone. “And the neighbors are good folks. You'll see. You'll be charmed. It's quite charming in a rustic kind of way.”

Fern knew what the word “rustic” meant. Reading books will give you an excellent vocabulary. (My old writing teacher used to say that reading

his

books and his books

alone

would give you an even better vocabulary. Although I respect his paunchy belly and his horn-rimmed spectacles and his way of pronouncing things much like an overeducated British butler, I didn't always agree with him on every point. In fact, perhaps I wasn't his favorite student.) Fern thought she was going to a farm, a charming, rustic farm. But “rustic” is a tricky word. They'd driven away from Tamed Hedge Road, away from Twin Oaks toward seedier and

seedier parts of town. There were neon signs in storefront windows, car dealerships, run-down houses and abandoned lots. The Bone pulled in front of a string of houses separated by alleys as narrow as a rat's rump. He bumped up over the curb, then the car plopped down with a disgusted sigh. The houses backed up to a railroad track. The yards were nearly bald. The grass patches, interrupted by mud-pocks, were mowed raggedly. He looked at his own yard and sighed deeply. A man was standing there, shuffling his feet around, his head bobbing back and forth.

Now, Fern liked adventure. One of her favorite books was about a boy who came home from school to find a tollbooth in his bedroom, and he drove a toy car through it into a different world, which sounds a little absurd to me. But as much as Fern liked reading about adventure, she was feeling a little nervous about the one she was actually having as she stared at the Bone's neighborhood. It was growing dark. There was only one streetlight working. The others looked like they'd been smashed by rocks. She kept an eye out for the dark cloud. Was it hovering behind the tire swing? Was it behind the Dumpster? Fern thought of the Drudgers at their house, where maybe they were teaching Howard to brush his teeth in small circular motions, and she was glad she wasn't there, but was she glad she was here instead?

The Bone got out of the car. Fern did too. She grabbed the black umbrella and her bag, feeling the top for the hard outline of her diary, which held her mother's picture. She slammed the heavy door behind her.

The next-door neighbor, a woman with a mop of blond and black hair, sat on her front stoop smoking. She said, “He been here a good couple hours, just strutting around like that.” Aside from the pecking movements of his head and the occasional flap of his arms, the man looked normal, wearing corduroys, a white shirt, an ugly necktie, and a leather belt. He seemed absorbed in the pecking and strutting and hadn't noticed Fern or the Bone yet.

The Bone nodded. He took Fern's bag for her, hoisting it to his shoulder. “We'll have to make a run for it.” He paused, then called out to the neighbor lady, “We expecting a train soon?”

“We're always expecting a train soon. They come every five minutes! Only way I tell time. Look, you gonna do anything about him?” the woman asked.

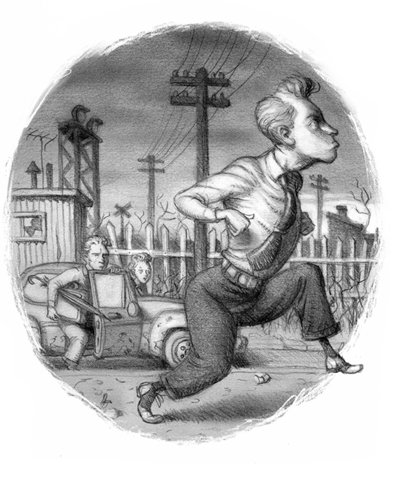

The Bone didn't answer. He lifted his head, straining forward. Fern could hear a small rumble in the distance. “Train,” the Bone said. “Wait, wait⦔ The train was getting closer now, closer, the noise rising up. This startled the man. He began bobbing frantically. “Now!” the Bone shouted. The train rattled loudly, creating a gust of wind. The man was squawking. The Bone ducked his

head and ran quickly past the man. Fern followed. The Bone was at the door now, rummaging for keys. Fern glanced over her shoulder at the neighbor woman and the man in the yard. The train had passed and the man was settling down.

“I know you know him,” the woman shouted.

“I don't,” the Bone shouted back.

“He ain't going to howl, is he? He ain't going to start to hoot or something and go all night? I'll call the police if that kind of mess starts up again. You hear me?”

“It'll be fine,” the Bone assured her. “He's a stranger. Maybe he's lost. I'm sure he'll go away on his own. It'll be fine!”

But it didn't seem that way to Fern. The man had fixed his eyes on Fern and the Bone. He was now high-stepping it toward them. Just before he was in striking distanceâand it did look like he was angry about somethingâthe Bone found the key, jiggled the lock, opened the door, hustled Fern inside and slammed it.

“Who's that?” Fern asked, shaken.

“Who?” the Bone asked.

“That man in the yard?”

“Him? Oh, well. I'm not perfect,” the Bone said. “Hypnosis is a tricky business. Anyone will tell you that. Sometimes things go a little haywire. He signed a contract, though. Fair and square. He's got no grounds to come after me.”

“You said you didn't know him,” Fern said with a small accusation in her tone. The Bone lied. That's what Fern was figuring out. He lied a little bit quite often, and although this made her a little bit mad, she also understood it. Being Fern Drudger had entailed a

good bit of lying, too. Only now she knew she hadn't been making up the things she saw. She hadn't been fibbing when the Drudgers accused her of it, no. But she

had

been lying in a way every time she narrowed her eyes for them, every time she kept her mouth shut when she wanted to let a choir out of her chest. She'd lied by being the way they wanted her to be. And why had she lied to them? Well, to please them, to make things easier for them. And wasn't that what the Bone was trying to do? He wanted things to go smoothly, for the man in the yard to be a stranger so that everything could be nice, for himself, but maybe for Fern, too. Maybe he wanted Fern to like him.

But here's a little fact: Lying to a fellow liar is quite tough. Liars are the best at catching liars. And so his lies didn't work on Fern. She'd catch him every time. And maybe this was the biggest relief of all: Her lies wouldn't work on him either. She couldn't pretend to be a Drudger in front of the Bone. He'd see right through her, just like he had at the swimming pool when he was Mrs. Lilliopole, wearing the plastic nose-pinch and the flowered bathing cap and the skirted swimsuit. He knew that she had seen the bat and the marble, and she wasn't just any kid, but

his

kid.

“I don't, technically, know any roosters. And that's what he is.” Fern looked at him in such a way that he knew she knew better, and he smiled a small, guilty smile

accompanied by a small, guilty shrug.

The Bone flipped on the light switch, illuminating a small hallway. There were two doors: one to the right, the other straight ahead. The Bone unlocked the door to the right. “We only have the bottom floor. The Bartons live upstairs. They're clog dancers, I'm sorry to report.” (I'd like to add here that the Bartons, though you'll never meet them in this book, are actually quite famous clog dancersâthat is, in clog-dancing circles, which tend to be very, very small circles.)

They stepped into the apartment. It was still dark and muffled, too, with a distant

ching, ching, ching

of little tiny bells. Although Fern didn't know the names for everything she smelled, here were a few: garlic, heavy Indian incense, blooming narcissus, Chinese food gone bad, cedar chips, mothballs, a mix of oranges and onions, and mint.

The Bone flipped a wall switch. A dim light flickered on and at the same time music came on, too, from a radio in the cornerâhorns and a singer singing, “Hope the sun gonna shine, hope the sun, hope the sun, hope the sun gonna shine on down.” The walls were draped in velvety cloths, like in a movie theater. And there was artwork on top of the draping: framed shoe inserts, a fish made out of tea bags, a painting of dental floss, which made Fern think how funny and beautiful and sad life was all at the same time. They were nothing

like the single painting in the Drudgers' living room of the Drudgers' living room, which only made one think of the Drudgers' living room. There was a card table with pop-out legs and two folding chairs, an orange knit sofa and a bunch of beanbag chairs that'd seen fluffier days. The Bone walked quickly to the windows that were covered by heavy curtains. He pulled each one back, peering out. “Spies,” he told Fern. “The Miser knows something's going on. He's hired a ring of spies. They press their cups against the windows and try to hear what my next step will be.”

It was hard to believe that anyone would spy on a place this strange and small and unofficial looking. Fern had a more glamorous impression of spiesâfor example, that they had equipment that was higher tech than cups pressed to windowsâbut she could tell that the Bone believed in the spies, even if she didn't (not yet, at least).

Fern turned around in a slow circle, taking the place in. She'd always wanted to feel at home someplace in the world, but was this it? She doubted it. It didn't feel like home, not really, but she kind of liked it all the same. It was so different. That's what she liked about it most of all.

The Bone walked into the cramped kitchen. He could only open the refrigerator door six inches before it hit the opposite wall. “Are you hungry? Thirsty?”

“Both,” Fern said.

“I've got an onion. Oranges. A can of mushroom soup.” He pulled out some Chinese leftovers, sniffed and tossed them in a plastic garbage can.

“Sounds fine.”

“I used to have a dog,” the Bone said. “But when we went to the circus, you know, where Howard tried the unicycle, the dog decided to stay. He had some high-quality tricks and, I suppose, thought he was wasting his talent on such a small audience as Howard and me and sometimes Marty.”

Fern wandered around the living room. There was still a good bit of dog fur, an extra coat on the sofas.

“Why do they call you the Bone?” she asked.

“I'm as tough as a bone. I'm not at all soft,” said the Bone, but he was a little flustered, like he didn't care for the question, like he was lying. “I've always been called the Bone and so that's that.”

“Okay,” Fern said. She didn't want to upset him.

When the Bone came in with the food, Fern was holding a framed photograph. It was a picture of the Bone and an enormous man with a boxy nose, arched black eyebrows, dark-circled eyes. The two were standing, laughing, pointing at each other.

“Your mother,” the Bone said, a hitch in his voice, “took that picture. That guy was my best friend. But not now.”