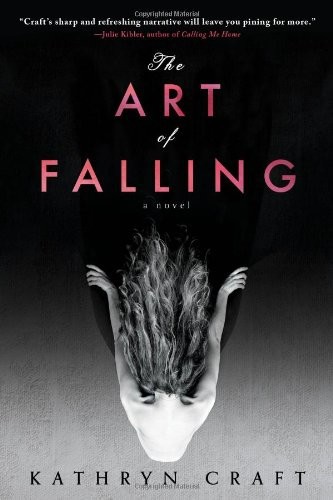

The Art of Falling

Read The Art of Falling Online

Authors: Kathryn Craft

Copyright © 2014 by Kathryn Craft

Cover and internal design © 2014 by Sourcebooks, Inc.

Cover design by Eileen Carey

Cover image © Robert Jones/Arcangel Images; Stockbyte/Getty Images

Sourcebooks and the colophon are registered trademarks of Sourcebooks, Inc.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means including information storage and retrieval systems—except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews—without permission in writing from its publisher, Sourcebooks, Inc.

The characters and events portrayed in this book are fictitious or are used fictitiously. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental and not intended by the author.

Published by Sourcebooks Landmark, an imprint of Sourcebooks, Inc.

P.O. Box 4410, Naperville, Illinois 60567-4410

(630) 961-3900

Fax: (630) 961-2168

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Craft, Kathryn.

The art of falling / Kathryn Craft.

pages cm

(pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Women dancers—Fiction. 2. Accident victims—Fiction 3. Falls (Accidents)—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3603.R338A78 2014

813’.6—dc23

2013031054

To Ellen,

who taught me

the meaning of

always

and

To Dave,

whose love

unlocked the stories

“The very first thing I discovered was that the body’s natural, instantaneous movement—its very first movement—is a falling movement. If you stand perfectly still and do not try to control the movement, you will find that you will begin to fall…”

—Doris Humphrey, modern dance pioneer

My muscles still won’t respond. It’s been hours since they promised a doctor, but no one has come. All I can do is lie on this bed, wishing for some small twinge to tell me exactly what is wrong. My body: a still life, with blankets.

I’d settle for inching my foot back beneath the covers. I command my foot to flex. To point. To burrow beside its mate. It ignores me, as do my hands when I tell them to tend to the situation.

Why has someone covered me so haphazardly? Or—could it be?—that in my dreams, I had somehow moved that foot? I will it to move again—now.

It stays put.

This standoff grows more frightening by the moment. If my focus weakens, I’ll fall prey to larger, hungrier questions. Only motion can soothe me; only sweat can wash away my fear.

From somewhere to my right, I hear an old woman’s crackling cough. My eyes look toward the sound, but I am denied even this small diversion; a flimsy curtain hides her.

I close my eyes against this new reality: the bed rails, a constant beeping over my shoulder, and the device clamped to my index finger. In my mind, I replace the flimsy curtain with a stretch of burgundy velour and relax into its weight. Sink. Deep. I replay each sweep, rise, and dramatic dip of Dmitri’s choreography. My muscles seek aspects of motion: that first impulse. The building momentum. Moments of suspension, then—ah, sweet release. When the curtain rises, I will be born anew.

• • •

“Is time.

Merde

.” The half-whisper I remember is intimate; Dmitri’s breath tickles my ear. With a wet finger, he grazes a tender spot on my neck, for luck, then disappears among the other bodies awaiting him. My skin tingles from his touch.

The work light cuts off, plunging me into darkness. On the other side of the curtain, eleven hundred people, many of them critics and producers, hush. We are about to premiere

Zephyr

, Dmitri’s first full-evening work.

I follow small bits of fluorescent tape across the floor to find my place. The curtain whispers as it rises. Audience expectation thickens the air.

Golden light splashes across the stage, and the music begins. Dmitri stalks onstage. I sense him and turn. Our eyes lock. We crouch—slow. Low. Wary. Mirror images, we raise our arms to the side, the downward arc from each shoulder creating powerful wings that hover on an imagined breeze. One: Our blood surges in rhythm. Two: A barely perceptible

plié

to prepare. Three: We soar.

Soon our limbs compress, then tug at the space between us. We never touch but are connected by intent, instinct, and strands of sound from violins. I feel the air he stirs against my skin.

Other dancers enter and exit, but I don’t yield; Dmitri designed their movements to augment the tension made by our bodies.

I become the movement. I fling my boundaries to the back of the house; I will be bigger than ever before. I’m a confluence of muscle and sinew and bone made beautiful through my command of the oldest known language. I long to move others through my dancing because then I, too, am moved.

Near the end of the piece, the other four dancers cut a diagonal slash between Dmitri and me. Our shared focus snaps. Dissonance grows as we perform dizzying turns.

The music slows and our arms unfold to reduce spin. Dmitri and I hit our marks and reach toward each other. We have danced beyond the end of the music. In silence, within a waiting pool of light, we stretch until we touch, fingertip to fingertip.

Light fades, but the dance continues; my energy moves through Dmitri, and his pierces me. The years, continents, and oceans that once held us apart could not keep us from this moment of pure connection.

Utter blackness surrounds us, and for one horrible moment I lose it all—Dmitri, the theater, myself.

But when the stage lights come up, Dmitri squeezes my hand. His damp curls glisten.

Applause crescendos and crashes over us. Dmitri winks before accepting the accolades he expects.

I can’t recover as quickly.

No matter how gently I ease toward the end of motion, it rips away from me. I feel raw. Euphoria drains from my fingertips, leaving behind this imperfect body.

I struggle to find myself as the others run on from the wings. We join hands in a line, they pull me with them to the lip of the stage—and with these simple movements I am returned to the joyful glow of performance. We raise our hands high and pause to look up to the balcony, an acknowledgment before bowing that feels like prayer. My heart and lungs strain and sweat pushes through my pores and I hope never to recover. I am gloriously alive, and living my dream.

The dance recedes and the applause fades, but I’m not ready. My muscles seek aspects of motion—where’s the motion?—I can feel no impulse. Momentum stalls. I am suspended and can find no release.

The curtain falls, the bed rails return, and I am powerless to stop them.

I sensed someone watching me. How long had I been asleep? I opened my eyes and saw, staring back at me from the foot of my bed, a man dressed in white.

“Finally.” The sound of my voice encouraged me, relying as it did upon the coordination of lips and jaw and tongue and vocal cords and diaphragm. Earlier, a woman from the hospital admissions office had only forms and questions; I needed action and answers. “You’ve got to get these drugs out of my system. My brain—it can’t talk to my body. It’s freaking me out.”

“I’m not a doctor.”

Salt-and-pepper hair parted on one side and a large nose slanting away created a question mark on the man’s face that mirrored my own confusion.

“Then what’s with the whites?”

“You don’t recognize me? I’m the baker. From the first floor of your building. Marty Kandelbaum.” He held a white box beneath his arm. “I had to come and make sure you were all right.”

“Why?”

“I suppose it was the way you said your name,” he said. “I heard such anguish. Such defiance. I’ve thought of little else.”

“We spoke?”

“I was there when you…” He raised his eyebrows.

I waited.

“Had your…” The man looked around as if he’d left the rest of the sentence lying somewhere in the room. “You know. Your accident.”

An accident—was that why I was here? I tried to remember something. Anything.

He patted my arm and gave me a sweet smile. “You’re lucky to be alive.”

Lucky

to

be

alive?

I took another inventory, head to toe—but felt nothing. Oh god.

Oh

god

. “Where am I hurt?” Breath fragmenting, nerves sparking, room spinning—

A small woman burst into the room. She wore a navy blue suit and sneakers. Kandelbaum turned and put up his hand; she stopped.

“But I need to know if she’s all right,” she said.

The woman looked familiar. Important somehow—

think!

—but my brain felt as stagnant as my body. I slowed my breathing to take in more oxygen. My rib cage responded—thank god. Thank god it could move. I would never again take breathing for granted.

I asked Kandelbaum who she was, and he said, “You don’t recognize her, either? You might tell your doctor.” Behind the curtain, the old woman in the bed beside mine coughed several times, evoking a lifespan marked out with cigarette butts. In a raspy voice, she apologized.

Kandelbaum stepped forward and lowered his voice. “Memory loss can be a sign of serious brain trauma. How many fingers?” He waved his hand so frantically I couldn’t focus.

The woman in the suit pushed past him. She had a pointed nose and chin, and gray hair sprouted from beneath a little red hat. I tried to jump-start my memory by placing her in other settings; nothing about my life looked right from this pillow.

“Penelope Sparrow. It

is

you. I’m so glad you’ve come ’round.”

“You know my name?”

“My dear.” Her voice softened. “Of course I do. You are one of the most compelling dancers I’ve ever seen.” Her gaze drifted over my covers, as if seeking some vestige of that dancer within its hilly landscape.

I pictured her face looking up at me from the audience. Wearing that red hat.

The woman reassembled her composure. “Plus, it’s my job to know you. I’m—”

“Margaret MacArthur.”

She smiled coyly. “I’m flattered.”

One of the most powerful dance critics in the Northeast, MacArthur had covered the Philadelphia dance scene for decades. But I’d never met her. To me, Margaret MacArthur was a byline, an incisive opinion, and an aisle seat in Row L.

She held a pair of red gloves, each finger tinged brown with age. Beneath them she’d concealed a small notebook. She flipped open its cover. “How are you feeling?”

I’d somehow scored my first interview with a revered dance critic, and I couldn’t answer her opening question. “Why do you want to know?”

Kandelbaum said, “She’s writing an article.”

“About what?” I said.

“I was filing a late review when your name came across the police scanner,” MacArthur said. “My editor let me cover your story. I’ve been up all night waiting to hear if you’re all right.”

“Police?”

MacArthur looked at Kandelbaum, then back at me, and flipped rather awkwardly through her notebook. She did not look at ease in the role of reporter. “What do you recall about what happened last night, around one a.m.?”

I’d been here since last night. After some sort of accident. I gave my name to a worried baker. A tired dance critic is covering the story. And all I can think is, what story?

Once again Kandelbaum broke the awkward silence. “I don’t think she remembers.”

MacArthur nodded. She started to speak, then stopped, as if at a loss as to how to continue. Finally, she dropped the professional demeanor. “Perhaps if we back up to the last day you danced. How were you feeling then, dear?”

The

last

day

you

danced

. The words pierced my heart. I struggled to keep my face neutral and my tone conversational, but my voice sounded watery even to my ears. “You know something about my condition. Have you spoken to my doctor?”

“Of course not.”

“I know something about that.” My roommate’s voice drifted over from her side of the room. “Can we open the curtain?”

When Kandelbaum stepped forward, I said, “Let me.”

The curtain hung just inches from my side. I was as determined to perform as I’d been in any audition, on any stage. I would lift my arm and open this curtain. And for a full minute or more, I tried. But the desire that boiled through my veins only succeeded in pushing sweat through my pores. My leaden body lay stiff. Even my hair felt heavy.

MacArthur watched my show of impotence. It was Kandelbaum who saved me from complete humiliation. “Don’t worry, Penelope. I’ll get it for you.”

The charity in his tone unhinged me.

Damn

. I did not want to cry in front of MacArthur.

Ball bearings scraped in a recessed track as he easily swept the curtain aside and my roommate’s world spilled into mine.

My first impression of Angela Reed was color. Color so rich and distracting it momentarily lifted my despair. My neck rotated, a small movement that a moment ago seemed beyond hope. Festive prisms dangled from the vivid Tiffany lamp on her bedside table. Sunset pinks, oranges, and purples draped her bed, and a half-moon rug warmed the floor. Even her cell phone had a fuchsia cover. Intricate construction paper flowers decorated the far wall.

MacArthur excitedly pressed pen to paper. “And who might you be?”

Angela spelled out her name. “It’s so cool to be bunking with a celebrity,” she said.

Only then did I look at her face. Angela wasn’t the old woman I’d expected. When she smiled, her freckled nose crinkled. Kinky hair radiated from her head like sunrays. Beneath a nightgown swirled like Van Gogh’s starry sky, she had the wisplike figure choreographers covet. A hot pink cast braced her forearm and right elbow.

My roommate’s bed hummed as she raised its head. “Your surgeon came by while you were sleeping,” Angela said. “He won’t be back till tomorrow.”

I craved this information—but not with MacArthur in the room.

“Surgeon?” MacArthur said.

“Your arm is broken, up near the shoulder. He pinned it,” Angela blurted. “Your incision’s about…” The fingers on her good hand estimated its size.

I made a quick calculation from Angela’s sign language. Two inches. Maybe it wasn’t so bad. But why no feeling—were the nerves damaged? I studied the topography of my blanket. My left arm lay useless across my rib cage.

Kandelbaum proffered the white box he’d been holding. I caught a whiff of danger—the same sweet, greasy scent coming from my hair. Why would that be? After an awkward lag, he opened the box.

“You brought me fastnachts?”

He nodded. “I made them myself.”

“Why?”

He seemed wary, as if I’d asked a trick question. “I’m a baker.”

“I’ve been to Independence Sweets,” Angela said. “Good éclairs. But what’s a fastnacht?”

“Fried dough,” Kandelbaum said, with enthusiasm. “Eating fried dough before Lenten fasting is an old German ritual believed to expel the evil spirits that brought the dead of winter. So spring can come. You see, Penelope? Life begins anew.”

He displayed the glistening brown lumps like a proud father. I scraped together the energy to say something polite. “They’re shiny.”

“I glaze them,” he said, almost apologetically. “I sell more that way.” I asked him to put the box on my bedside table, one short push from the trash can.

“How did we start talking about fried dough?” MacArthur said.

My roommate issued a breathy laugh that outlasted any amusement MacArthur’s comment could have possibly prompted. It soon disintegrated into coughing so intense I feared she couldn’t breathe.

“Do something!” I said. But Kandelbaum and MacArthur just watched in shock as Angela’s face turned an alarming red. I crawled my fingers across the sheet, dragging my useless arm behind, and pushed the call button. “It’s Angela,” I said, hoping the intercom would pick up my voice. “She can’t breathe.”

A male nurse burst through the door with a cartful of equipment and yanked the curtain between our beds shut. My heart raced from the emergency and my adrenaline-fueled victory—I had moved my fingers.

Kandelbaum and MacArthur watched the curtain respectfully, as if it took respiratory distress to remind them that hospitals serve the ailing. I heard thumping, skin on skin. Choking sounds. Then, finally, wet coughs.

Angela said, “Put that away.”

“But the doctor ordered it.”

“Whose body is this, anyway?” she said. “Just write ‘treatment refused.’”

The nurse reappeared, his face as red as his hair.

MacArthur put her pen in her purse. “I have to make deadline. I intend to see your story is told, Penelope.”

Once MacArthur left, Kandelbaum moved to my side. “What were you doing last night? You could have killed yourself.”

Exhaustion weighed down my eyelids, and there, in the darkness, I saw Dmitri. His hungry eyes, the waves in his hair, his taut body springing through space.

If

only

you

would

come

home, Dmitri. Talk to me. Apologize.

When I opened my eyes, Kandelbaum awaited an answer.

A female voice from the intercom behind me said, “You rang for help, Penelope?”

“I did?” I looked down—I still had the call button clutched in my hand.

“Are you in pain?”

The enormity of my loss seized my heart, squeezing from it the last drops of my lifeblood. I answered, “Yes.”

“We can give you more pain meds in another hour.”

An hour. A gauntlet during which I could do nothing but let the second hand hack away at me with its razor-sharp edges.

“Here.” Kandelbaum dunked a washcloth into a cup of water and pressed it to my forehead. The gesture felt unexpectedly intimate. I closed my eyes and meditated on the cool, the wet, and a man’s caring hand against my brow.

“Why, you’ve spilled some juice on your sleeve,” he said, blotting at my shoulder. Then: “Oh dear. Oh dear…”

I opened my eyes. The cloth in Kandelbaum’s shaking hand was blood red.

The dance drew me back to the stage. I closed my eyes, and the burgundy velour dropped, and I hardly felt Kandelbaum rip the call button from my hand.

• • •

The second morning, when at last I had the opportunity to get answers from my surgeon, I felt too groggy to form complete questions. “Surgery? Again?”

“It was just a little bleed,” he said. “We needed to go in and correct some vascular damage we hadn’t picked up at first.”

“What else?” I managed. “Besides the shoulder?” When I braced for the news, I was able to curl my fingers.

The doctor held an x-ray up to the light over my bed. “Nothing. Not one rib broken. Amazing.” He swapped the film for another. “A smaller pelvis would have shattered.”

My big bones. As if I needed x-ray proof. I whispered, “But I can’t move.”

“Have you tried today?”

What an ass. I aimed to prove my point by straining to lift my head from the pillow. My stiff neck engaged my abdominals, which in turn detonated hidden charges along the length of my spine. I took a breather, my grimace almost a smile. Pain:

Welcome

back, you sonofabitch

. I tried again, funneling all my energy into isolating head flexors. Neck muscles shuddered, but my chin did move toward my chest.

My head dropped back onto the pillow. Without warning, the doctor pulled my arm from its sling and pushed it up. As if he had flipped a switch, my body screamed to life in excruciating glory. “What the hell?”

He typed a note into his laptop. “Your arm is stable. I pinned it.”

After a lifetime of fighting this damned body, it was fighting back. The doctor left me to my private war.

Dance training taught me I could detach from physical pain if I controlled my breathing. In—two—three…out—two—three…in—two—three…out—two—three…. But before I could get a grip on the situation, a man who introduced himself as Dr. Tom walked in.

He asked my name. My answer, on an exhalation, was weak and breathy. He checked my answer against my wristband.

“I understand you’re a dancer.”

“I was.”

“You’ve retired?”

“Look at me.” My body remained hopelessly inert.

“How did you fall?”

This tidbit interrupted the rhythm of my breathing. “I fell?”

“You don’t remember your accident? With the car?”

“I don’t remember being in a car. Is this brain damage?”

“I’m not a neurologist. I’m a psychiatrist.” He opened his laptop and hit a few keys. “It says here you live in the Independence Suites.” He paused. “Number 1408.” He paused again. “The apartment is rented to…” He scrolled the page.

“Dmitri DeLaval,” I said, hoping to speed this up. “Or the University of the Arts, I’m not sure which.” Another slow breath helped to both manage pain and allow time to seek other hard facts I might tuck in around my fuzzy memory. “The lease expires soon. Is it February 28 yet?”