The Art of Manliness - Manvotionals: Timeless Wisdom and Advice on Living the 7 Manly Virtues (10 page)

Authors: Brett McKay

And twenty years after, on the other side of the globe, against the filth of dirty foxholes, the stench of ghostly trenches, the slime of dripping dugouts, those boiling suns of the relentless heat, those torrential rains of devastating storms, the loneliness and utter desolation of jungle trails, the bitterness of long separation of those they loved and cherished, the deadly pestilence of tropic disease, the horror of stricken areas of war.

Their resolute and determined defense, their swift and sure attack, their indomitable purpose, their complete and decisive victory—always victory, always through the bloody haze of their last reverberating shot, the vision of gaunt, ghastly men, reverently following your password of Duty, Honor, Country.

The code which those words perpetuate embraces the highest moral laws and will stand the test of any ethics or philosophies ever promulgated for the uplift of mankind. Its requirements are for the things that are right, and its restraints are from the things that are wrong. The soldier, above all other men, is required to practice the greatest act of religious training—sacrifice. In battle and in the face of danger and death, he discloses those divine attributes which his Maker gave when he created man in his own image. No physical courage and no brute instinct can take the place of the Divine help which alone can sustain him. However horrible the incidents of war may be, the soldier who is called upon to offer and to give his life for his country, is the noblest development of mankind.

The long gray line has never failed us. Were you to do so, a million ghosts in olive drab, in brown khaki, in blue and gray, would rise from their white crosses, thundering those magic words: Duty, Honor, Country.

This does not mean that you are warmongers. On the contrary, the soldier above all other people prays for peace, for he must suffer and bear the deepest wounds and scars of war. But always in our ears ring the ominous words of Plato, that wisest of all philosophers: “Only the dead have seen the end of war.”

The shadows are lengthening for me. The twilight is here. My days of old have vanished—tone and tints. They have gone glimmering through the dreams of things that were. Their memory is one of wondrous beauty, watered by tears and coaxed and caressed by the smiles of yesterday. I listen then, but with thirsty ear, for the witching melody of faint bugles blowing reveille, of far drums beating the long roll.

In my dreams I hear again the crash of guns, the rattle of musketry, the strange, mournful mutter of the battlefield. But in the evening of my memory I come back to West Point. Always there echoes and re-echoes: Duty, Honor, Country.

“Courage is not simply one of the virtues, but the form of every virtue at the testing point.” —C.S. Lewis

F

ROM

“S

ONG OF

M

YSELF

,” 1855

By Walt Whitman

I understand the large hearts of heroes,

The courage of present times and all times,

How the skipper saw the crowded and rudderless wreck of the steamship, and Death chasing it up and down the storm,

How he knuckled tight and gave not back an inch, and was faithful of days and faithful of nights,

And chalk’d in large letters on a board,

Be of good cheer, we will not desert you

;How he follow’d with them and tack’d with them three days and would not give it up,

How he saved the drifting company at last,

How the lank loose-gown’d women look’d when boated from the side of their prepared graves,

How the silent old-faced infants and the lifted sick, and the sharp-lipp’d unshaved men;

All this I swallow, it tastes good, I like it well, it becomes mine,

I am the man, I suffer’d, I was there.

“Courage is contagious. When a brave man takes a stand, the spines of others are often stiffened.” —Billy Graham

A

N

A

ESOP’S

F

ABLE

A hunter, not very bold, was searching for the tracks of a Lion. He asked a man felling oaks in the forest if he had seen any marks of his footsteps, or if he knew where his lair was. “I will,” he said, “at once show you the Lion himself.” The Hunter, turning very pale, and chattering with his teeth from fear, replied, “No, thank you. I did not ask that; it is his track only I am in search of, not the Lion himself.”

The hero is brave in deeds as well as words.

“Courage is resistance to fear, mastery of fear

—not absence of fear. Except a creature be part coward, it is not a compliment to say it is brave; it is merely a loose misapplication of the word. Consider the flea!—incomparably the bravest of all the creatures of God, if ignorance of fear were courage.”

—Mark Twain

F

ROM

T

OM

B

ROWN’S

S

CHOOL

D

AYS

, 1857

By Thomas Hughes

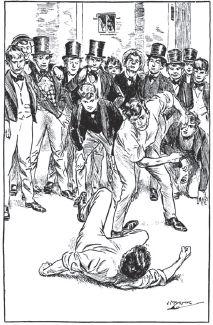

Tom Brown’s School Days

was a popular nineteenth-century novel that followed eleven-year-old Tom Brown, as he adjusted to life at a public boarding school for boys and learned how to become a young gentleman. The following excerpts refer to Tom’s only big fight at the school. The headmaster had given him a student to look after, and when a large bully attacked the frail and sensitive boy, Tom stepped in to stop the beating and fight the bully himself.

After all, what would life be without fighting, I should like to know? From the cradle to the grave, fighting, rightly understood, is the business, the real, highest, honestest business of every son of man. Every one who is worth his salt has his enemies, who must be beaten, be they evil thoughts and habits in himself or spiritual wickedness in high places, or Russians, or Border-ruffians, or Bill, Tom, or Harry, who will not let him live his life in quiet till he has thrashed them.

It is no good for Quakers, or any other body of men, to uplift their voices against fighting. Human nature is too strong for them, and they don’t follow their own precepts. Every soul of them is doing his own piece of fighting, somehow and somewhere. The world might be a better world without fighting, for anything I know, but it wouldn’t be our world; and therefore I am dead against crying peace when there is no peace, and isn’t meant to be. I’m as sorry as any man to see folk fighting the wrong people and the wrong things, but I’d a deal sooner see them doing that, than that they should have no fight in them.

As to fighting, keep out of it if you can, by all means. When the time comes, if it ever should, that you have to say “Yes” or “No” to a challenge to fight, say “No” if you can—only take care you make it clear to yourselves why you say “No.” It’s a proof of the highest courage, if done from true Christian motives. It’s quite right and justifiable, if done from a simple aversion to physical pain and danger. But don’t say “No” because you fear a licking, and say or think it’s because you fear God, for that’s neither Christian nor honest. And if you do fight, fight it out; and don’t give in while you can stand and see.

“Live as brave men and face adversity with stout hearts.” —Horace

F

ROM

L

AYS OF

A

NCIENT

R

OME

, 1842

By Thomas Babington Macaulay

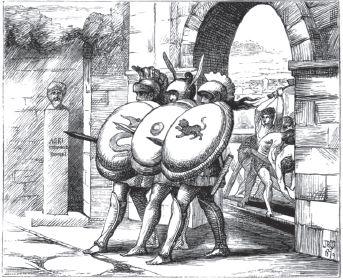

While serving the English government in India during the 1830s, politician, poet, and historian Thomas Babington Macaulay spun semi-mythical ancient Roman tales into memorable ballads or “lays.” His most famous lay was “Horatius,” a ballad that recounted the legendary courage of an ancient Roman army officer, Publius Horatius Cocles. In the fifth century B.C., Rome rebelled against Etruscan rule and ousted their last king, Lucius Tarquinius Superbus, to form a republic. But the king refused to go quietly into the night; he enlisted the help of Lars Porsena of Clusium in an attempt to overthrow the new Roman government and re-establish his reign.

In a battle against the approaching Etruscans, the Roman army faced defeat and began to retreat across the bridge which traversed the Tiber River. And this is where we’ll let the poem pick up the heroic tale.

Manly factoid: “Horatius” was a favorite of Winston Churchill who is said to have memorized all seventy stanzas of the poem as a boy (we’ve included thirty-four of them here).

And nearer fast and nearer

Doth the red whirlwind come;

And louder still and still more loud,

From underneath that rolling cloud,

Is heard the trumpet’s war-note proud,

The trampling, and the hum.

And plainly and more plainly

Now through the gloom appears,

Far to left and far to right,

In broken gleams of dark-blue light,

The long array of helmets bright,

The long array of spears.

Fast by the royal standard,

O’erlooking all the war,

Lars Porsena of Clusium

Sat in his ivory car.

By the right wheel rode Mamilius,

Prince of the Latian name;

And by the left false Sextus,

That wrought the deed of shame.

But when the face of Sextus

Was seen among the foes,

A yell that rent the firmament

From all the town arose.

On the house-tops was no woman

But spat towards him and hissed;

No child but screamed out curses,

And shook its little fist.

But the Consul’s brow was sad,

And the Consul’s speech was low,

And darkly looked he at the wall,

And darkly at the foe.

“Their van will be upon us

Before the bridge goes down;

And if they once may win the bridge,

What hope to save the town?”

Then out spake brave Horatius,

The Captain of the Gate:

“To every man upon this earth

Death cometh soon or late.

And how can man die better

Than facing fearful odds,

For the ashes of his fathers,

And the temples of his gods,

“And for the tender mother

Who dandled him to rest,

And for the wife who nurses

His baby at her breast,

And for the holy maidens

Who feed the eternal flame,

To save them from false Sextus

That wrought the deed of shame?

“Haul down the bridge, Sir Consul,

With all the speed ye may;

I, with two more to help me,

Will hold the foe in play.

In yon strait path a thousand

May well be stopped by three.

Now who will stand on either hand,

And keep the bridge with me?”

Then out spake Spurius Lartius;

A Ramnian proud was he:

“Lo, I will stand at thy right hand,

And keep the bridge with thee.”

And out spake strong Herminius;

Of Titian blood was he:

“I will abide on thy left side,

And keep the bridge with thee.”

“Horatius,” quoth the Consul,

“As thou sayest, so let it be.”

And straight against that great array

Forth went the dauntless Three.

For Romans in Rome’s quarrel

Spared neither land nor gold,

Nor son nor wife, nor limb nor life,

In the brave days of old.

Now while the Three were tightening

Their harness on their backs,

The Consul was the foremost man

To take in hand an axe:

And Fathers mixed with Commons

Seized hatchet, bar, and crow,

And smote upon the planks above,

And loosed the props below.

Meanwhile the Tuscan army,

Right glorious to behold,

Come flashing back the noonday light,

Rank behind rank, like surges bright

Of a broad sea of gold.

Four hundred trumpets sounded

A peal of warlike glee,

As that great host, with measured tread,

And spears advanced, and ensigns spread,

Rolled slowly towards the bridge’s head,

Where stood the dauntless Three.

The Three stood calm and silent,

And looked upon the foes,

And a great shout of laughter

From all the vanguard rose:

And forth three chiefs came spurring

Before that deep array;

To earth they sprang, their swords they drew,

And lifted high their shields, and flew

To win the narrow way;

Aunus from green Tifernum,

Lord of the Hill of Vines;

And Seius, whose eight hundred slaves

Sicken in Ilva’s mines;

And Picus, long to Clusium

Vassal in peace and war,

Who led to fight his Umbrian powers

From that gray crag where, girt with towers,

The fortress of Nequinum lowers

O’er the pale waves of Nar.

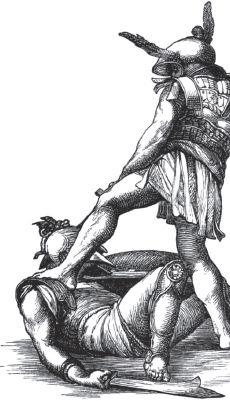

Stout Lartius hurled down Aunus

Into the stream beneath;

Herminius struck at Seius,

And clove him to the teeth;

At Picus brave Horatius

Darted one fiery thrust;

And the proud Umbrian’s gilded arms

Clashed in the bloody dust.

Then Ocnus of Falerii

Rushed on the Roman Three;

And Lausulus of Urgo,

The rover of the sea;

And Aruns of Volsinium,

Who slew the great wild boar,

The great wild boar that had his den

Amidst the reeds of Cosa’s fen,

And wasted fields, and slaughtered men,

Along Albinia’s shore.

Herminius smote down Aruns:

Lartius laid Ocnus low:

Right to the heart of Lausulus

Horatius sent a blow.

“Lie there,” he cried, “fell pirate!

No more, aghast and pale,

From Ostia’s walls the crowd shall mark

The track of thy destroying bark.

No more Campania’s hinds shall fly

To woods and caverns when they spy

Thy thrice accursed sail.”

But now no sound of laughter

Was heard among the foes.

A wild and wrathful clamor

From all the vanguard rose.

Six spears’ lengths from the entrance

Halted that deep array,

And for a space no man came forth

To win the narrow way.

But all Etruria’s noblest

Felt their hearts sink to see

On the earth the bloody corpses,

In the path the dauntless Three:

And, from the ghastly entrance

Where those bold Romans stood,

All shrank, like boys who unaware,

Ranging the woods to start a hare,

Come to the mouth of the dark lair

Where, growling low, a fierce old bear

Lies amidst bones and blood.

Yet one man for one moment

Strode out before the crowd;

Well known was he to all the Three,

And they gave him greeting loud.

“Now welcome, welcome, Sextus!

Now welcome to thy home!

Why dost thou stay, and turn away?

Here lies the road to Rome.”

Thrice looked he at the city;

Thrice looked he at the dead;

And thrice came on in fury,

And thrice turned back in dread:

And, white with fear and hatred,

Scowled at the narrow way

Where, wallowing in a pool of blood,

The bravest Tuscans lay.

But meanwhile axe and lever

Have manfully been plied;

And now the bridge hangs tottering

Above the boiling tide.

“Come back, come back, Horatius!”

Loud cried the Fathers all.

“Back, Lartius! Back, Herminius!

Back, ere the ruin fall!”

Back darted Spurius Lartius;

Herminius darted back:

And, as they passed, beneath their feet

They felt the timbers crack.

But when they turned their faces,

And on the farther shore

Saw brave Horatius stand alone,

They would have crossed once more.

But with a crash like thunder

Fell every loosened beam,

And, like a dam, the mighty wreck

Lay right athwart the stream:

And a long shout of triumph

Rose from the walls of Rome,

As to the highest turret-tops

Was splashed the yellow foam.

And, like a horse unbroken

When first he feels the rein,

The furious river struggled hard,

And tossed his tawny mane,

And burst the curb and bounded,

Rejoicing to be free,

And whirling down, in fierce career,

Battlement, and plank, and pier,

Rushed headlong to the sea.

Alone stood brave Horatius,

But constant still in mind;

Thrice thirty thousand foes before,

And the broad flood behind.

“Down with him!” cried false Sextus,

With a smile on his pale face.

“Now yield thee,” cried Lars Porsena,

“Now yield thee to our grace.”

Round turned he, as not deigning

Those craven ranks to see;

Nought spake he to Lars Porsena,

To Sextus nought spake he;

But he saw on Palatinus

The white porch of his home;

And he spake to the noble river

That rolls by the towers of Rome.

“Oh, Tiber! Father Tiber!

To whom the Romans pray,

A Roman’s life, a Roman’s arms,

Take thou in charge this day!”

So he spake, and speaking sheathed

The good sword by his side,

And with his harness on his back,

Plunged headlong in the tide.

No sound of joy or sorrow

Was heard from either bank;

But friends and foes in dumb surprise,

With parted lips and straining eyes,

Stood gazing where he sank;

And when above the surges,

They saw his crest appear,

All Rome sent forth a rapturous cry,

And even the ranks of Tuscany

Could scarce forbear to cheer.

But fiercely ran the current,

Swollen high by months of rain:

And fast his blood was flowing;

And he was sore in pain,

And heavy with his armor,

And spent with changing blows:

And oft they thought him sinking,

But still again he rose.

Never, I ween, did swimmer,

In such an evil case,

Struggle through such a raging flood

Safe to the landing place:

But his limbs were borne up bravely

By the brave heart within,

And our good father Tiber

Bare bravely up his chin.

“Curse on him!” quoth false Sextus;

“Will not the villain drown?

But for this stay, ere close of day

We should have sacked the town!”

“Heaven help him!” quoth Lars Porsena

“And bring him safe to shore;

For such a gallant feat of arms

Was never seen before.”

And now he feels the bottom;

Now on dry earth he stands;

Now round him throng the Fathers;

To press his gory hands;

And now, with shouts and clapping,

And noise of weeping loud,

He enters through the River-Gate

Borne by the joyous crowd.

They gave him of the corn-land,

That was of public right,

As much as two strong oxen

Could plough from morn till night;

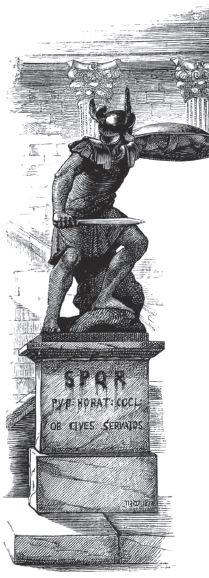

And they made a molten image,

And set it up on high,

And there it stands unto this day

To witness if I lie.

It stands in the Comitium

Plain for all folk to see;

Horatius in his harness,