The Ascent of Man (6 page)

Authors: Jacob Bronowski

Everything in nomad life is immemorial. The Bakhtiari have always travelled alone, quite unseen. Like other nomads, they think of themselves

as a family, the sons of a single founding father. (In the same way the Jews used to call themselves the children of Israel or Jacob.) The Bakhtiari take their name from a legendary herdsman of Mongol times, Bakhtyar. The legend of their own origin that they tell of him begins,

And the father of our people, the hill-man, Bakhtyar, came out of the fastness of the southern mountains in ancient

times. His seed were as numerous as the rocks on the mountains, and his people prospered.

The biblical echo sounds again and again as the story goes on. The patriarch Jacob had two wives, and had worked as a herdsman for seven years for each of them. Compare the patriarch of the Bakhtiari:

The first wife of Bakhtyar had seven sons, fathers of the seven brother lines of our people. His second

wife

had four sons. And our sons shall take for wives the daughters from their father’s brothers’ tents, lest the flocks and tents be dispersed.

As with the children of Israel, the flocks were all-important; they are not out of the mind of the storyteller (or the marriage counsellor) for a moment.

Before 10,000

B.C

nomad peoples used to follow the natural migration of wild herds. But sheep and

goats have no natural migrations. They were first domesticated about ten thousand years ago – only the dog is an older camp follower than that. And when man domesticated them, he took on the responsibility of nature; the nomad must lead the helpless herd.

The role of women in nomad tribes is narrowly defined. Above all, the function of women is to produce men-children; too many she-children are

an immediate misfortune, because in the long run they threaten disaster. Apart from that, their duties lie in preparing food and clothes. For example, the women among the Bakhtiari bake bread – in the biblical manner, in unleavened cakes on hot stones. But the girls and the women wait to eat until the men have eaten. Like the men, the lives of the women centre on the flock. They milk the herd,

and they make a clotted yoghourt from the milk by churning it in a goatskin bag on a primitive wooden frame. They have only the simple technology that can be carried on daily journeys from place to place. The simplicity is not romantic; it is a matter of survival. Everything must be light enough to be carried, to be set up every evening and to be packed away again every morning. When the women spin

wool with their simple, ancient devices, it is for immediate use, to make the repairs that are essential on the journey – no more.

It is not possible in the nomad life to make things that will not be needed for several weeks. They could not be carried. And in fact the Bakhtiari do not know how to make them. If they need metal pots, they barter them from settled peoples or from a caste of gipsy

workers who specialise in metals. A nail, a stirrup, a toy, or a child’s bell is something that is traded from outside the tribe. The Bakhtiari life is too narrow to have time or skill for specialisation. There is no room for innovation, because there is not time, on the move, between evening and morning, coming and going all their lives, to develop a new device or a new thought – not even a new

tune. The only habits that survive are the old habits. The only ambition of the son is to be like the father.

It is a life without features. Every night is the end of a day like the last, and every morning will be the beginning of a journey like the day before. When the day breaks, there is one question in everyone’s mind: Can the flock be got over the next high pass? One day on the journey,

the highest pass of all must be crossed. This is the pass Zadeku, twelve thousand feet high on the Zagros, which the flock must somehow struggle through or skirt in its upper reaches. For the tribe must move on, the herdsman must find new pastures every day, because at these heights grazing is exhausted in a single day.

Every year the Bakhtiari cross six ranges of mountains on the outward journey

(and cross them again to come back). They march through snow and the spring flood water. And in only one respect has their life advanced beyond that of ten thousand years ago. The nomads of that time had to travel on foot and carry their own packs. The Bakhtiari have pack-animals – horses, donkeys, mules – which have only been domesticated since that time. Nothing else in their lives is new.

And nothing is memorable. Nomads have no memorials, even to the dead. (Where is Bakhtyar, where was Jacob buried?) The only mounds that they build are to mark the way at such places as the Pass of the Women, treacherous but easier for the animals than the high pass.

The spring migration of the Bakhtiari is a heroic adventure; and yet the Bakhtiari are not so much heroic as stoic. They are resigned

because the adventure leads nowhere. The summer pastures themselves will only be a stopping place – unlike the children of Israel, for them there is no promised land. The head of the family has worked seven years, as Jacob did, to build a flock of fifty sheep and goats. He expects to lose ten of them in the migration if things go well. If they go badly, he may lose twenty out of that fifty.

Those are the odds of the nomad life, year in and year out. And beyond that, at the end of the journey, there will still be nothing except an immense, traditional resignation.

Who knows, in any one year, whether the old when they have crossed the passes will be able to face the final test: the crossing of the Bazuft River? Three months of melt-water have swollen the river. The tribesmen, the

women, the pack animals and the flocks are all exhausted. It will take a day to manhandle the flocks across the river. But this, here, now is the testing day. Today is the day on which the young become men, because the survival of the herd and the family depends on their strength. Crossing the Bazuft River is like crossing the Jordan; it is the baptism to manhood. For the young man, life for a moment

comes alive now. And for the old – for the old, it dies.

What happens to the old when they cannot cross the last river? Nothing. They stay behind to die. Only the dog is puzzled to see a man abandoned. The man accepts the nomad custom; he has come to the end of his journey, and there is no place at the end.

The largest single step in the ascent of man is the change from nomad to village agriculture.

What made that possible? An act of will by men, surely; but with that, a strange and secret act of nature. In the burst of new vegetation at the end of the Ice Age, a hybrid wheat appeared in the Middle East. It happened in many places: a typical one is the ancient oasis of Jericho.

Jericho is older than agriculture. The first people who came here and settled by the spring in this otherwise desolate

ground were people who harvested wheat, but did not yet know how to plant it. We know this because they made tools for the wild harvest, and that is an extraordinary piece of foresight. They made sickles out of flint which have survived; John Garstang found them when he was digging here in the 1930s. The ancient sickle edge would have been set in a piece of gazelle horn, or bone.

There no longer

survives, up on the hill or tel and its slopes, the kind of wild wheat that the earliest inhabitants harvested. But the grasses that are still here must look very like the wheat that they found, that they gathered for the first time by the fistful, and cut with that sawing motion of the sickle that reapers have used for all the ten thousand years since then. That was the Natufian pre-agricultural

civilisation. And, of course, it could not last. It was on the brink of becoming agriculture. And that was the next thing that happened on the Jericho tel.

The turning-point to the spread of agriculture in the Old World was almost certainly the occurrence of two forms of wheat with a large, full head of seeds. Before 8000

BC

wheat was not the luxuriant plant it is today; it was merely one of

many wild grasses that spread throughout the Middle Fast. By some genetic accident, the wild wheat crossed with a natural goat grass and formed a fertile hybrid. That accident must have happened many times in the springing vegetation that came up after the last Ice Age. In terms of the genetic machinery that directs growth, it combined the fourteen chromosomes of wild wheat with the fourteen chromosomes

of goat grass, and produced Emmer with twenty-eight chromosomes. That is what makes Emmer so much plumper. The hybrid was able to spread naturally, because its seeds are attached to the husk in such a way that they scatter in the wind.

Jericho is monumental, older than the Bible, layer upon layer of history, a city.

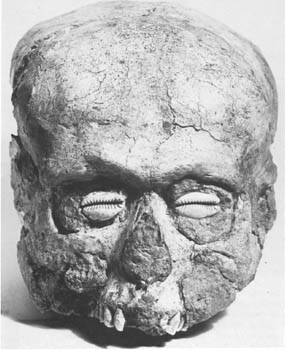

Jericho is monumental, older than the Bible, layer upon layer of history, a city.From the Jericho site: plaster-decorated skull inset with cowrie shells

.

The tower at Jericho tel. Its masonry is flint-worked and pre-7000

BC

. The modern grid covers the hollow shaft inside the tower

.

For such a hybrid to be fertile is rare but not unique among plants. But now the story of the rich plant life that

followed the Ice Ages becomes more surprising. There was a second genetic accident, which may have come about because Emmer was already cultivated. Emmer crossed with another natural goat grass and produced a still larger hybrid with forty-two chromosomes, which is bread wheat. That was improbable enough in itself, and we know now that bread wheat would not have been fertile but for a specific

genetic mutation on one chromosome.

Yet there is something even stranger. Now we have a beautiful ear of wheat, but one which will never spread in the wind because the ear is too tight to break up. And if I do break it up, why, then the chaff flies off and every grain falls exactly where it grew. Let me remind you, that is quite different from the wild wheats or from the first, primitive hybrid,

Emmer. In those primitive forms the ear is much more open, and if the ear breaks up then you get quite a different effect – you get grains which will fly in the wind. The bread wheats have lost that ability. Suddenly, man and the plant have come together. Man has a wheat that he lives by, but the wheat also thinks that man was made for him because only so can it be propagated. For the bread wheats

can only multiply with help; man must harvest the ears and scatter their seeds; and the life of each, man and the plant, depends on the other. It is a true fairy tale of genetics, as if the coming of civilisation had been blessed in advance by the spirit of the abbot Gregor Mendel.

A happy conjunction of natural and human events created agriculture. In the Old World that happened about ten thousand

years ago, and it happened in the Fertile Crescent of the Middle East. But it surely happened more than once. Almost certainly agriculture was invented again and independently in the New World – or so we believe on the evidence we now have that maize needed man like wheat. As for the Middle East, agriculture was spread here and there over its hilly slopes, of which the climb from the Dead Sea

to Judea, the hinterland of Jericho, is at best a characteristic piece and no more. In a literal sense, agriculture is likely to have had several beginnings in the Fertile Crescent, some of them before Jericho.

Yet Jericho has several features which make it historically unique and give it a symbolic status of its own. Unlike the forgotten villages elsewhere, it is monumental, older than the Bible,

layer upon layer of history, a city. The ancient sweet-water city of Jericho was an oasis on the edge of the desert whose spring has been running from prehistoric times right into the modern city today. Here wheat and water came together and, in that sense, here man began civilisation. Here, too, the bedouin came with their dark muffled faces out of the desert, looking jealously at the new way

of life. That is why Joshua brought the tribes of Israel here on their way to the Promised

Land – because wheat and water, they make civilisation: they make the promise of a land flowing with milk and honey. Wheat and water turned that barren hillside into the oldest city of the world.

All at once at that time Jericho is transformed. People come and soon become the envy of their neighbours, so

that they have to fortify Jericho, turn it into a walled city, and build a stupendous tower, nine thousand years ago. The tower is thirty feet across at the base and, to correspond, almost thirty feet in depth. And climbing up beside it the excavation reveals layer upon layer of past civilisation: the early pre-pottery men, the next pre-pottery men, the coming of pottery seven thousand years ago;

early copper, early bronze, middle bronze. Each of these civilisations came, conquered Jericho, buried it, and built itself up; so that the tower lies not so much under forty-five feet of soil as under forty-five feet of past civilisations.