The Attacking Ocean (19 page)

Read The Attacking Ocean Online

Authors: Brian Fagan

Tags: #The Past, #Present, #and Future of Rising Sea Levels

Figure 8.1

Artist’s impression of the Lothal dockyard. Archaeological Survey of India/Omar Khan Images of Asia.

The flood threat increased gradually as the river mouth silted up over three centuries. All the authorities could do was to raise house foundations and change the levels of municipal drains. One particularly destructive flood even damaged the thirteen-meter-thick platforms that supported the upper city. Many buildings in the lower town collapsed; streets filled with flood debris; floodwaters breached the embankment walls of the dockyard. Community leaders quickly deployed large numbers of people to clear drains, rebuild houses, and expand the city. Lothal reached the zenith of its prosperity in 2000 B.C.E., so much so that the people apparently became complacent and allowed flood defense works to fall into disrepair. At this point, the second villain appeared on stage—a massive tropical cyclone.

Severe tropical cyclones tend to form in the north Indian Ocean, on either side of the Indian Peninsula, between April and December, with peaks in May and November.

5

Major cyclones are relatively uncommon in the Arabian Sea, but those that do occur bring very strong winds,

produce high waves, and, above all, spawn powerful sea surges. In June 2007, Cyclone Gonu, a Category 5 storm with 258-kilometer-an-hour winds, descended on Oman at the mouth of the Persian Gulf, only the third such storm to hit land there since 865 C.E. Fortunately the narrow mouth of the Gulf weakened the storm, which caused widespread flooding and loss of life in both Oman and the United Arab Emirates. At the time when Lothal was a major port, sea levels in the Gulf were higher, which would have made it possible for a cyclone to surge as far north as southern Mesopotamia.

In the absence of modern forecasting tools, predicting cyclones far ahead of their arrival is virtually impossible, beyond telltale cloud effects, rising humidity, and strengthening gusty winds some days and hours ahead. The damage wrought by winds blowing at 120 kilometers an hour or more is severe enough, but it pales into insignificance alongside the sea surges, which sweep everything before them and can raise sea levels by twelve meters without warning. The surge may last only a few hours, but the damage is done. The destruction is particularly severe when the surge coincides with a high tide.

Cyclones have a long history in the Arabian Sea, but unfortunately we have no record of them before scientific records began in the nineteenth century. Many of the floods that afflicted Lothal and other coastal cities resulted from exceptional monsoon rains, but the most severe blows came with cyclonic storm surges such as one that swept ashore in about 2000 B.C.E. Such events are entirely different from monsoon floods, when floodwaters rise more slowly and there is at least some warning of pending trouble. Four thousand years ago, the powerful surge arrived suddenly. Raging water submerged the Acropolis and warehouses, and also entire quarters of the city. Lothal effectively ceased to exist within a few hours. Overseas trade came to a standstill; many of the inhabitants fled permanently to higher ground.

Only a small settlement rose on the submerged ruins of Lothal. The survivors repaired the dockyard embankments, but they now had to dig a two-kilometer canal to link the port to the river. Even then, only small ships could be locked through the inlet. Larger cargo vessels had to moor alongside a quay in the river. The volume of overseas trade was

now so small that the city declined into obscurity and lost contact with the great Indus cities. Ironically, the floodwaters accumulated a five-meter-high mound that seemingly rendered the ravaged city immune from further flood damage. The natural defense was an illusion. Another massive sea surge a century later obstructed the normal flow of the spring tides, choked the natural drainage system, and turned the entire estuary into a huge lake. Villages, towns, irrigation works, and dams vanished before the deluge. This time the dockyard disappeared under a huge silt deposit, never to be restored. All political authority appears to have evaporated. A rectangular city protected from flooding by a thirteen-meter brick wall finally vanished forever. At the time, the ocean was only few kilometers from Lothal. Today, silt buildup resulting from flood and rising sea levels means that it is now over twenty kilometers inland.

We have only a dim understanding of the complex geological forces that contributed to sea level changes along the western Indian coast. We know that coastal uplift along the northern margins of the Arabian Sea as well as earth movements may have contributed to the vulnerability of Lothal and other coastal settlements. The same general conditions affected later societies living along the western coast, but the main destruction stemmed not from sea level rise or subsidence, but from heavy monsoon rains and from extreme weather events—tropical cyclones. As they had in earlier Harappan times, farmer and city dweller alike lived in a monsoon environment, where the intensity of the seasonal rains made all the difference between famine and plenty. The failure of the monsoon, often associated with strong El Niños in the southwestern Pacific, could kill hundreds of thousands of farmers, even millions, as happened in the late nineteenth century with the epochal western Indian famine of 1878.

6

A strong La Niña condition, the opposite swing of the Pacific climatic seesaw, could bring exceptionally heavy rains. Such deluges were just as destructive as drought, especially in coastal regions where ponding and silt accumulation could destroy valuable irrigation works and farmland.

The destruction wrought by extreme weather events along the western coasts of what are now India and Pakistan over centuries and millennia can only be guessed at. All we have as a basis for comparison is historical

and modern experience in Bangladesh at the head of the Bay of Bengal on the other side of India, where millions of people live only a few meters above sea level and farm at the mercy of monsoon rains and the capricious violence of tropical cyclones.

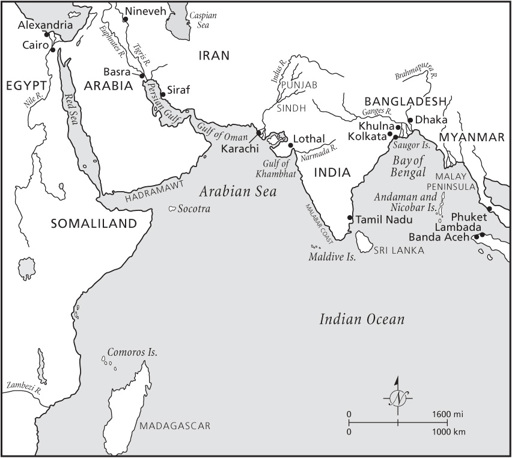

Figure 8.2

Map showing locations in

chapter 8

.

ABOUT 80 PERCENT of Bangladesh is alluvial floodplain, most of it less than ten meters above sea level, the world’s largest river delta formed by the Ganges, Brahmaputra, and Meghna Rivers. Water covers some ten thousand square kilometers of the country. Much larger areas flood during the monsoon season. Only some landscapes far inland have more rugged topography, bisected by fast-flowing rivers. The delta coastline extends over about six hundred kilometers facing the Bay of Bengal.

Tidal action molds the shoreline, where an arabesque of waterways large and small cuts through the coastal plain, the largest of them about half a kilometer wide. Strong tidal streams keep the river channels long and straight as they flow through clay and silt deposits that resist erosion. Easily eroded sand forms banks and small islands at the river mouths, which strong southwesterly monsoon winds convert into dunes above the high-water mark. Mudflats of fine sediment form behind them and eventually become islands. This dynamic environment, a unique mosaic of beach and tidal forests, and also dense mangrove swamps, acted as an important cushion against sea surges and cyclones. Two hundred years ago, more than eleven thousand square kilometers of mangrove swamps and forests protected the coast. Today this natural coastal barrier is under threat from promiscuous forest clearance for agricultural land, for shrimp farming, and to construct barrages for irrigation works.

Right up to the coast, the delta soils are fertile and ideal for all kinds of crops, among them rice and cotton, so it is hardly surprising that numerous farmers live close to the sea. Unfortunately, their homeland lies at the head of the Bay of Bengal, which narrows like a funnel toward its northern coast. Fierce tropical storms with their accompanying sea surges form in the open sea, then barrel northward, gathering strength as they approach the coast. A shallow continental shelf heightens the surges as they move inshore, making them higher than in many other parts of the world.

Cyclones and their fearsome sea surges descend on Bangladesh with a furious intensity that has killed millions of people over the centuries. Between 1947 and 1988 alone, thirteen severe cyclones have ravaged the lowlands causing thousands of deaths and sweeping away villages and defensive embankments. Over the next century, projected sea level rises of a meter or more will intensify the maritime siege.

Countless sea surges have attacked the low-lying Bengal coast since Lothal in the west was in its heyday four thousand years ago.

7

This may be why flood stories loom large in ancient Indian religious works like the Hindu Satapatha Brahmana with its myths of creation and of a huge flood, compiled between 800 and 500 B.C.E.—an equivalent to the

Great Flood in Genesis.

8

Monsoon floods were a routine part of the seasonal round, even if they were unusually large, whereas a huge storm surge driven by a cyclone was something to be remembered beyond the span of a single generation. Unfortunately we have no accurate records of cyclonic events until the nineteenth century, but there can be little doubt that the sequence of meteorological events was much the same far into the past. We know, for example, from Indian records that in 1582 C.E., a five-hour cyclone and associated sea surge killed an estimated half million people in what was then Bengal. Only Hindu temples with strong foundations survived the attack.

There are listings of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century storms, but there is little information on casualties or damage until the founding of the Indian Meteorology Department in 1875, which came about as a direct result of the severe cyclone of 1864, the first to be recorded in any detail. The report on the storm came from a plethora of meteorological observations, official reports, letters, ships’ logs, and firsthand accounts. By modern standards, it’s a patchwork of impressions, but it is brought to life by eyewitness reports, written or recorded when memories were horrifyingly fresh.

9

The weather was blessedly dry in Kolkata (Calcutta) on October 4, 1864. After five months of heavy monsoon rains, there had been no showers for several days. The air felt clean and dry with less humidity than usual. British officials and local people alike reveled in the calm, pleasant day with its light winds. No one knew that the barometer was falling sharply to the south in the center of the Bay of Bengal. A cyclone had formed over a circular area about 650 kilometers across. Unsettled, squally conditions affected a wide area, including the Andaman Islands. Ships’ logs hint at rough weather as early as October 3. The steamship

Conflict

experienced “frightful squalls with very heavy rain.” A day later, the storm center advanced toward the mouth of the Hooghly River and in the direction of an unsuspecting Kolkata 130 kilometers upstream. “Furious squalls from the north, with torrents of rain” hit the northward-bound steamer

Clarence

. Strong northerly winds, high seas, and heavy rain showers lashed the Bengal coast. The pilot vessel at the mouth of the Hooghly slipped her anchor cable and ran offshore for

safety. Vicious waves washed away her quarter boat and threw the ship on her beam-ends until the mainmast was cut away.

Figure 8.3

Ships on the Hooghly River, Kolkata (Calcutta), after the 1867 cyclone. Samuel Bourne/British Library.

The next day the storm center passed over the coast. A tug anchored off the Saugor lighthouse at the Hooghly River mouth steamed at full power into the teeth of the wind while still at anchor. The cable parted; the wind dropped for three quarters of an hour as the storm center passed overhead, then resumed with savage gusts that blew the vessel onto its beam-ends, “burying her in a sheet of foam to the top of the funnel.” As the wind finally dropped, the tug went aground off an unfamiliar shore and dried out at low tide. Fortunately the captain was able to back off as the water rose and anchored safely.

10