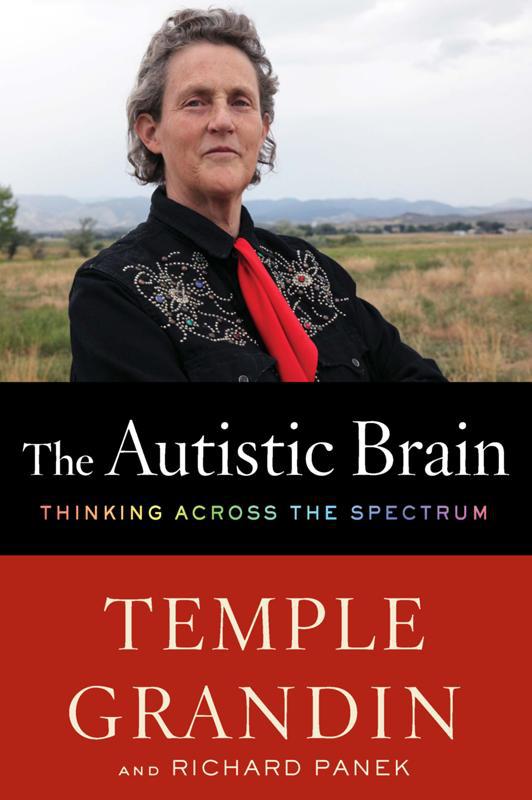

The Autistic Brain: Thinking Across the Spectrum

Read The Autistic Brain: Thinking Across the Spectrum Online

Authors: Temple Grandin,Richard Panek

Tags: #Non-Fiction

Lighting Up the Autistic Brain

Part II: Rethinking the Autistic Brain

From the Margins to the Mainstream

Sample Chapter from ANIMALS MAKE US HUMAN

Copyright © 2013 by Temple Grandin and Richard Panek

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

THIS BOOK PRESENTS THE RESEARCH AND IDEAS OF ITS AUTHORS. IT IS NOT INTENDED TO BE A SUBSTITUTE FOR CONSULTATION WITH A PROFESSIONAL CLINICIAN. THE PUBLISHER AND THE AUTHORS DISCLAIM RESPONSIBILITY FOR ANY ADVERSE EFFECTS RESULTING DIRECTLY OR INDIRECTLY FROM INFORMATION CONTAINED IN THIS BOOK.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Grandin, Temple.

The autistic brain : thinking across the spectrum / Temple Grandin and Richard Panek.

pages cm

ISBN

978-0-547-63645-0 (hardback)

1. Autism spectrum disorders. 2. Autistic people—Mental health. 3. Autism—Research. 4. Psychology, Pathological. I. Panek, Richard. II. Title.

RC

553.

A

88

G

725 2013

616.85'882—dc23 2013000662

e

ISBN

978-0-547-85818-0

v1.0413

IN THIS BOOK

I will be your guide on a tour of the autistic brain. I am in the unique position to speak about both my experiences with autism and the insights I have gained from undergoing numerous brain scans over the decades, always with the latest technology. In the late 1980s, shortly after MRI became available, I jumped at the opportunity to travel on my first “journey to the center of my brain.” MRI machines were rarities in those days, and seeing the detailed anatomy of my brain was awesome. Since then, every time a new scanning method becomes available, I am the first in line to try it out. My many brain scans have provided possible explanations for my childhood speech delay, panic attacks, and facial-recognition difficulties.

Autism and other developmental disorders still have to be diagnosed with a clumsy system of behavioral profiling provided in a book called the

DSM,

which is short for

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders.

Unlike a diagnosis for strep throat, the diagnostic criteria for autism have changed with each new edition of the

DSM.

I warn parents, teachers, and therapists to avoid getting locked into the labels. They are not precise. I beg you: Do not allow a child or an adult to become defined by a

DSM

label.

The genetics of autism is an exceedingly complex quagmire. Many small variations in the genetic code that control brain development are involved. A genetic variation that is found in one autistic child will be absent in another autistic child. I will review the latest in genetics.

Researchers have done hundreds of studies on autistics’ problems with social communication and facial recognition, but they have neglected sensory issues. Sensory oversensitivity is totally debilitating for some people and mild in others. Sensory problems may make it impossible for some individuals on the autism spectrum to participate in normal family activities, much less get jobs. This is why my top priorities for autism research are accurate diagnoses and improved treatments for sensory problems.

Autism, depression, and other disorders are on a continuum ranging from normal to abnormal. Too much of a trait causes severe disability, but a little bit can provide an advantage. If all genetic brain disorders were eliminated, people might be happier, but there would be a terrible price.

When I wrote

Thinking in Pictures,

in 1995, I mistakenly thought that everybody on the autism spectrum was a photorealistic visual thinker like me. When I started interviewing other people about how they recalled information, I realized I was wrong. I theorized that there were three types of specialized thinking, and I was ecstatic when I found several research studies that verified my thesis. Understanding what kind of thinker you are can help you respect your limitations and, just as important, take advantage of your strengths.

The landscape I was born into sixty-five years ago was a very different place from where we are now. We’ve gone from institutionalizing children with severe autism to trying to provide them with the most fulfilling lives possible—and, as you will read in chapter 8, finding meaningful work for those who are able. This book will show you every step of my journey.

—TG

1

I

WAS FORTUNATE

to have been born in 1947. If I had been born ten years later, my life as a person with autism would have been a lot different. In 1947, the diagnosis of autism was only four years old. Almost nobody knew what it meant. When Mother noticed in me the symptoms that we would now label autistic—destructive behavior, inability to speak, a sensitivity to physical contact, a fixation on spinning objects, and so on—she did what made sense to her. She took me to a neurologist.

Bronson Crothers had served as the director of the neurology service at Boston Children’s Hospital since its founding, in 1920. The first thing Dr. Crothers did in my case was administer an electroencephalogram, or EEG, to make sure I didn’t have petit mal epilepsy. Then he tested my hearing to make sure I wasn’t deaf. “Well, she certainly is an odd little girl,” he told Mother. Then when I began to verbalize a little, Dr. Crothers modified his evaluation: “She’s an odd little girl, but she’ll learn how to talk.” The diagnosis: brain damage.

He referred us to a speech therapist who ran a small school in the basement of her house. I suppose you could say the other kids there were brain damaged too; they suffered from Down syndrome and other disorders. Even though I was not deaf, I had difficulty hearing consonants, such as the

c

in

cup.

When grownups talked fast, I heard only the vowel sounds, so I thought they had their own special language. But by speaking slowly, the speech therapist helped me to hear the hard consonant sounds, and when I said

cup

with a

c,

she praised me—which is just what a behavioral therapist would do today.

At the same time, Mother hired a nanny who played constant turn-taking games with my sister and me. The nanny’s approach was also similar to the one that behavioral therapists use today. She made sure that every game the three of us played was a turn-taking game. During meals, I was taught table manners, and I was not allowed to twirl my fork around over my head. The only time I could revert back to autism was for one hour after lunch. The rest of the day, I had to live in a nonrocking, nontwirling world.

Mother did heroic work. In fact, she discovered on her own the standard treatment that therapists use today. Therapists might disagree about the benefits of a particular aspect of this therapy versus a particular aspect of that therapy. But the core principle of every program—including the one that was used with me, Miss Reynolds’s Basement Speech-Therapy School Plus Nanny—is to engage with the kid one-on-one for hours every day, twenty to forty hours per week.

The work Mother did, however, was based on the initial diagnosis of brain damage. Just a decade later, a doctor would probably have reached a completely different diagnosis. After examining me, the doctor would have told Mother, “It’s a psychological problem—it’s all in her mind.” And then sent me to an institution.

While I’ve written extensively about autism, I’ve never really written about how the diagnosis itself is reached. Unlike meningitis or lung cancer or strep throat, autism can’t be diagnosed in the laboratory—though researchers are trying to develop methods to do so, as we’ll see later in this book. Instead, as with many psychiatric syndromes, such as depression and obsessive-compulsive disorder, autism is identified by observing and evaluating behaviors. Those observations and evaluations are subjective, and the behaviors vary from person to person. The diagnosis can be confusing, and it can be vague. It has changed over the years, and it continues to change.

The diagnosis of autism dates back to 1943, when Leo Kanner, a physician at Johns Hopkins University and a pioneer in child psychiatry, proposed it in a paper. A few years earlier,

he had received a letter from a worried father named Oliver Triplett Jr., a lawyer in Forest, Mississippi. Over the course of thirty-three pages, Triplett described in detail the first five years of his son Donald’s life. Donald, he wrote, didn’t show signs of wanting to be with his mother, Mary. He could be “perfectly oblivious” to everyone else around him too. He had frequent tantrums, often didn’t respond to his name, found spinning objects endlessly fascinating. Yet for all his developmental problems, Donald also exhibited unusual talents. He had memorized the Twenty-Third Psalm (“The Lord is my shepherd

.

.

.”) by the age of two. He could recite twenty-five questions and answers from the Presbyterian catechism verbatim. He loved saying the letters of the alphabet backward. He had perfect pitch.

Mary and Oliver brought their son from Mississippi to Baltimore to meet Kanner. Over the next few years, Kanner began to identify in other children traits similar to Donald’s. Was there a pattern? he wondered. Were these children all suffering from the same syndrome? In 1943, Kanner published a paper, “Autistic Disturbances of Affective Contact,” in the journal

Nervous Child.

The paper presented the case histories of eleven children who, Kanner felt, shared a set of symptoms—ones that we would today recognize as consistent with autism: the need for solitude; the need for sameness. To be alone in a world that never varied.

From the start, medical professionals didn’t know what to do with autism. Was the source of these behaviors biological, or was it psychological? Were these behaviors what these children had brought into the world? Or were they what the world had instilled in them? Was autism a product of nature or nurture?

Kanner himself leaned toward the biological explanation of autism, at least at first. In that 1943 paper,

he noted that autistic behaviors seemed to be present at an early age. In the final paragraph, he wrote, “We must, then, assume that these children have come into the world with innate inability to form the usual, biologically provided affective contact with people, just as other children come into the world with innate physical or intellectual handcaps [

sic

].”

One aspect of his observations, however, puzzled him. “It is not easy to evaluate the fact that all of our patients have come of highly intelligent parents. This much is certain, that there is a great deal of obsessiveness in the family background”—no doubt thinking of Oliver Triplett’s thirty-three-page letter. “The very detailed diaries and reports and the frequent remembrance, after several years, that the children had learned to recite twenty-five questions and answers of the Presbyterian Catechism, to sing thirty-seven nursery songs, or to discriminate between eighteen symphonies, furnish a telling illustration of parental obsessiveness.

“One other fact stands out prominently,” Kanner continued. “In the whole group, there are very few really warmhearted fathers and mothers. For the most part, the parents, grandparents, and collaterals are persons strongly preoccupied with abstractions of a scientific, literary, or artistic nature, and limited in genuine interest in people.”