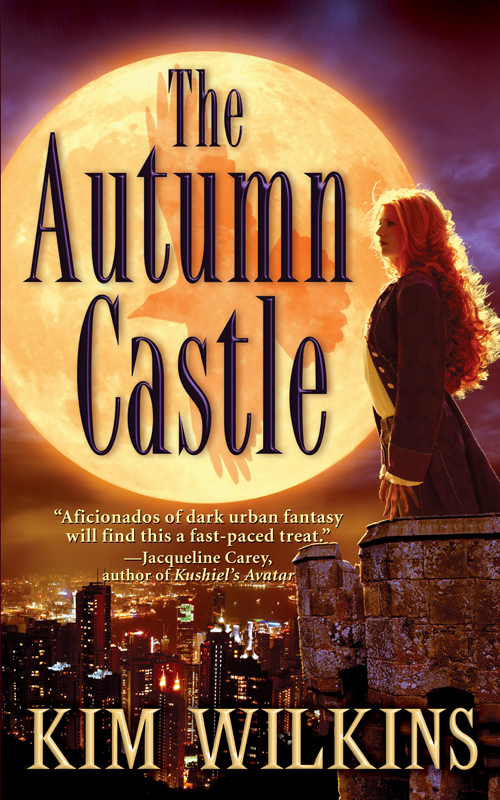

The Autumn Castle

Authors: Kim Wilkins

Copyright © 2003, 2005 by Kim Wilkins

All rights reserved.

Aspect

Warner Books

Hachette Book Group

237 Park Avenue, New York, NY 10017

Visit our website at

www.HachetteBookGroup.com

.

The Aspect name and logo are registered trademarks of Warner Books.

First eBook Edition: January 2005

ISBN: 978-0-446-55975-1

Contents

THE TALE OF SILVERHAND STARLIGHT

Mirko

Alles Liebe, So Weit Der Himmel Himmel Ist

—from the Memoirs of Mandy Z.

O

nce upon a time, a Miraculous Child was born. That night was the last of April—Walpurgis Night—on the summit of the Brocken

in the Harz Mountains. It has long been thought that the devil holds court on the Brocken on such a night, but I am not a

devil (for that Miraculous Child, dear reader, was me); I am the only son of the thirteenth generation of a special family.

In the dim, distant past, my ancestors bred with faeries, bringing our family line infinite good fortune, but making a terrible

mess of our gene pool.

My name is Immanuel Zweigler, but I am known as Mandy Z. I am an artist, renowned; I am wealthy beyond your wildest dreams,

and always have been, for my family has money in obscure bank accounts in sinister places the world over. I am color-blind,

truly color-blind. I see only black and white and gray, but if you wore a particularly vibrant color, perhaps a little of

its warmth would seep into my field of vision and be rendered the palest sepia. But I have an extraordinary sense of smell,

and an extraordinary sense of touch. That is why I like to sculpt.

You may wonder why someone so miraculous has waited until the age of forty-eight to commence his memoir. Simply, it had never

occurred to me to do so, but then the British journalist came to interview me. He was a genial man. We had a good conversation

and then I left him with the view from my west windows while I went upstairs to fetch a photograph—I always insist on providing

my own photographs to be published with interviews. I was rummaging in the drawer of my desk in my sculpture room, a room

I prefer to keep private, when I heard the British journalist clear his throat behind me.

“You should not have followed me in here,” I said.

“This is extraordinary,” he replied, advancing toward my latest sculpture.

Ah, the beautiful thing, so white and gleaming with gorgeous curves and ghastly crevices.

“It’s called the Bone Wife,” I told him as he ran his fingers over her hips (she only exists below the waist at present).

I was amused because he didn’t know what he was touching.

“Are you going to finish her?” he asked, gesturing to where her face would be.

“Oh yes. Though some would say she is the perfect woman just as she is.”

He didn’t laugh at my joke. “What medium are you using?”

“Bones.”

His fingers jumped off as though scalded. “Not human bones?”

I smiled and shook my head. “Of course not.”

So he returned to his examination, confident that these were the bones of unfortunate sheep and pigs, and then I gave him

his photos and asked him to leave. I sat for a long time looking at my Bone Wife, and mused about my continued disappointment

in how I am represented by the world’s media, and about how so much of what I do can never be made public. I wanted to read

about a version of myself that I recognized, even if I had to write it with my own pen; and that’s when I decided upon a memoir.

I decided to celebrate me. Miraculous me.

Not human bones?

No. The thought is as repulsive to me as it was to the British journalist. As is the thought of animal bones; I bear no grudge

against our four-legged companions. Not human bones, not animal bones. A rarer medium: faery bones. The bones of faeries I

have killed.

Because, you see, I have a measureless loathing for faeries. And I am the Faery Hunter.

There is nobody at home. Autumn fills the rooms;

Moonbright sonata

And the awakening at the edge of the twilit forest.

“Hohenburg,”

Georg Trakl

The water started to boil, and the flesh fell away from the bones, so he took the bones out and put them on the slab; he knew

not, however, in which order they should go, and arranged everything in a big muddle.

“Brother Lustig,”

Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm

P

lease don’t make me remember, please don’t make me remember.

Inevitable, however. Christine had known from the moment the man had glanced at her business card, his eyebrows shooting up.

“Starlight. That’s an unusual surname.”

“Mm-hm.”

“You’re not any relation to Alfa and Finn Starlight? The seventies pop stars?”

Pop stars! Her parents had considered themselves musicians, poets, artists. “Yeah, I’m their daughter.” Amazingly, her voice

came out smooth, almost casual. She didn’t need this today; she was already feeling unaccountably melancholy.

“Oh. Oh, I’m so . . .”

“Sorry?”

“Yes. Yes, I’m very sorry.”

Because he knew, as most people did, that Alfa and Finn Starlight had died in a horrific car accident from which their teenage

daughter had been the only survivor. Suddenly there was no point in resisting anymore: she was back there. The English Bookshop

on Ludwigkirchplatz, its long shelves and neat carpet squares, spun down to nothing in her perception; it was all blood and

metal and ground glass and every horror that those evil, stubborn thirty-five seconds of consciousness had forced her to witness.

“I’m sorry too,” she said. Her lower back twinged in sympathy with the remembrance. She wouldn’t meet the man’s gaze, trying

to discourage him. He was pale and clean-shaven, had a South African accent, and was clearly battling with his impulses. On

the one hand, he was aware it was rude—maybe even distressing for her—to keep asking about the accident; on the other hand,

he was talking with a real-life survivor of a famous and tragic legend. Christine was used to this four seconds of struggle:

enthusiasm versus compassion. Compassion never won.

“When was that again? 1988?” he asked.

“1989,” Christine replied. “November.”

“Yes, of course. My sister cried for days. She’d always had a crush on Finn.”

“I think a lot of women did.”

“He was a good-looking man, and your mother was beautiful too.”

Christine smiled in spite of herself, wondering if the man was now pondering how such stunning parents had managed to produce

such an ordinary-looking child.

“One thing I’ve always wanted to know,” he said, leaning forward.

Christine braced herself. Why couldn’t she ever tell these people to leave her alone? Why had she never developed that self-preserving

streak of aggression that would shut down his questions, lock up her memories. “Yes?”

“You were in a coma for eight weeks after the accident.”

“Yes.”

“The kid who ran you off the road didn’t stop.”

“No.”

“And there were no witnesses.”

“That’s right.”

“Then how did they find him and convict him?”

Yes, her back was definitely twinging now, a horrid legacy of the accident, the reason November 1989 was never really consigned

to the past, to that cold night and that long tunnel. Her doctor back home would tell her that these twinges were psychosomatic,

triggered by the memory. She had no idea what the word for “psychosomatic” was in German, and the doctor she had seen twice

since her arrival in Berlin two months ago was happy to prescribe painkillers without too much strained bilingual conversation.

“I was conscious for about half a minute directly after the accident,” she explained. “The kid who hit us stopped a second,

then took off. I got his license plate, I wrote it on the dash.”

“Really?” He was excited now, privy to some new juicy fact about the thirteen-year-old story. Many details had been withheld

from the press because the driver of the other car was a juvenile. The law had protected him from the barrage of media scrutiny,

while Christine had suffered the full weight of the world’s glare.

“I’m surprised you could collect yourself to find a pen, under the circumstances,” he continued. “It must have been traumatic.”

Oh, yes.

Her father crushed to death; her mother decapitated. Christine smiled a tight smile; time to finish this conversation. “If

you phone at the end of the week, we should be able to give you an estimated due date for that book. It’s a rare import, so

it could take a number of months.”

He hesitated. Clearly, he had a lot of other questions. Chief among them might be why the heir to the Starlight fortune was

working as a shop assistant in an English-language bookshop in Berlin.

“All right, then,” the man said. “I’ll see you when I come to pick it up.”

Christine nodded, silently vowing to make sure she was out back checking invoices when he returned.

He headed for the door, his footsteps light and carefree, and not weighed down with thirteen years of chronic pain, thirteen

years of nightmares about tunnels and blood, thirteen years of resigned suffering. A brittle anger rose on her lips.

“By the way,” she called.

He turned.

“I didn’t have a pen,” she said.

“Pardon?”

Had he forgotten already? Was that how much her misery meant to anybody else? “In the car, after the accident,” she said.

“You were right, I was too traumatized to find a pen.”

His face took on a puzzled aspect. “Then how . . . ?”

Christine held up her right index finger. “My mother’s blood,” she said. “Have a nice day.”

Gray. Black. Brown. No matter which way Christine surveyed it, this painting of Jude’s looked like every other painting he

had ever done. “It’s beautiful, darling.”

He lifted her hair and kissed the back of her neck. She pondered the colors, Jude’s colors of choice as long as she’d known

him. She often wondered if his preferences bore any relation to the reasons he was attracted to her. Jude was alternative

art’s pinup boy, with a wicked smile, a tangle of blond hair, and sparkling dark eyes. Christine, by contrast, knew she was

profoundly forgettable. She was thin but not sleek, pale but not luminous, her brown hair was thick but not shiny; and with

her button eyes, flat cheeks, and snub nose she possessed not even the distinction of ugliness. No matter how hard she tried

to be good-natured and generous and kind, Christine knew that she was cursed with invisibility.