The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy Into Action (30 page)

Read The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy Into Action Online

Authors: Robert S. Kaplan,David P. Norton

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Business

As a precursor for how key performance drivers can be communicated to external investors, take Skandia, a Swedish insurance and financial services

company. Skandia issues a supplement, called the

Business Navigator

, to its annual report. The supplement describes the company’s strategy, the strategic measures it uses to communicate, motivate, and evaluate the strategy, and performance along these measures during the past year. The introduction in Skandia’s 1994 annual report supplement, entitled “Visualizing Intellectual Capital at Skandia,” declares:

Commercial enterprises have always been valued according to their financial assets and sales, their real estate holdings, or other tangible assets. These views of the industrial age dominate our perception of businesses to this day—even though the underlying reality began changing decades ago. Today it is the service sector that stands for dynamism and innovative capacity

….

The service sector has few visible assets, however. What price does one assign to creativity, service standards or unique computer systems? Auditors, analysts, and accounting people have long lacked instruments and generally accepted norms for accurately valuing service companies and their “intellectual capital

.”

The supplement presents a

Business Navigator

for eight major lines of business.

2

The navigator for one line of business is shown in Figure 9-4.

Skandia is clearly taking a “lead-steer” position in voluntarily disclosing its business-unit scorecard objectives and measures to the financial community. It is doing so as part of its reporting and disclosure strategy, hoping to attract shareholders that are willing to invest for long-term results. These relationship investors take a significant long-term position in a company and, therefore, have a more intense interest in how the company is being managed for long-term economic results. Early indications are promising since investment analysis of Skandia now includes discussion of its products, technology, customers, and employee capabilities, not just financial forecasts.

Communication of the Balanced Scorecard’s objectives and measures is a first step in gaining individual commitment to the business unit’s strategy. But awareness is usually not sufficient by itself to change behavior. Somehow, the organization’s high-level strategic objectives and measures need to be translated into actions that each individual can take to contribute to

the organization’s goals. For example, an on-time delivery objective for the business unit’s customer perspective can be translated into an objective to reduce setup times at a bottleneck machine, or for rapid transfer of orders from one process to the next. In this way, local improvement efforts become aligned with overall organizational success factors.

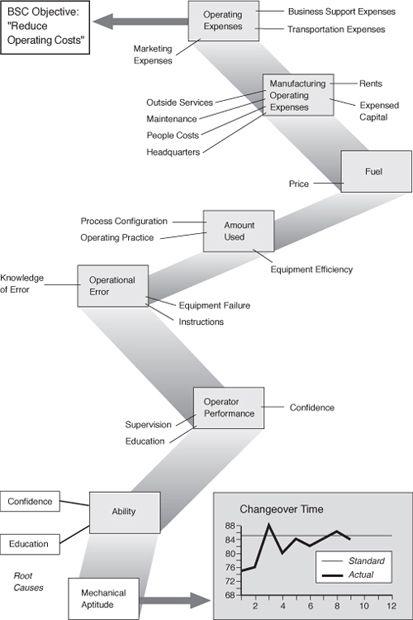

Many organizations, however, have found it difficult to decompose high-level strategic measures, especially nonfinancial ones, into local, operational measures. In the past, when managers relied exclusively on top-down financial controls, they could exploit an elegant decomposition of an aggregate measure, like return-on-investment or economic value-added, into local measures, like inventory turns, days sales in accounts receivable, operating expenses, and gross margins. Unfortunately, nonfinancial measures, such as customer satisfaction and information systems availability, are more difficult to decompose into more disaggregate elements. The Balanced Scorecard can make a unique contribution here since it is based on a “performance model” that identifies the drivers of strategy at the highest level. The scorecard’s framework of linked cause-and-effect relationships can be used to guide the selection of lower-level objectives and measures that will be consistent with high-level strategy. As illustrated in Figure 9-5, the high-level performance model reflected in the scorecard becomes the starting point for a decomposition process that cascades high-level measures down to lower organizational levels. The central concept is that an integrated performance model that defines that drivers of strategic performance at different organizational levels should be used as the central organizing framework for setting goals and objectives at all organizational levels. Thus, the Balanced Scorecard at the SBU level can be translated into a linked scorecard for lower-level departments, teams, and individuals. Several examples illustrate different approaches for implementing this concept.

Figure 9-4

Skandia’s Business Navigator

Figure 9-5

Cascading the Scorecard

Figure 9-6

Cascading Division Objectives into Specific Team Objectives

The big question faced by all companies is whether and how to link their formal compensation system to the scorecard measures. Currently, companies are following different strategies in how soon they link their compensation system to the measures. Ultimately, for the scorecard to create the cultural change, incentive compensation must be connected to achievement of scorecard objectives. The issue is not whether, but when and how the connection should be made.

Because financial compensation is such a powerful lever, some companies want to tie their compensation policy for senior managers to the scorecard measures as soon as possible. One organization shifted its bonus calculation for senior executives away from annual return-on-capital-employed targets; bonuses are now based 50% on achieving economic value-added targets over a three-year period, with the remaining 50% based on the formulation and achievement of scorecard measures in the three

nonfinancial perspectives. This policy has the obvious advantages of aligning the financial interests of the senior managers with achieving their business unit’s strategic objectives.

As another example, Pioneer Petroleum moved quickly to use its Balanced Scorecard as the sole basis for computing senior executive incentive compensation. As shown in Figure 9-8, it tied 60% of the executive bonus to financial performance. Pioneer, rather than relying on a single number for this component, developed a weighted average among five financial indicators: operating margin and return-on-capital, both measured against competitive benchmarks; cost reduction versus plan; and growth in both existing and new markets. It based the remaining 40% of the bonus on indicators drawn from the customer, internal process, and learning and growth perspectives, including a key indicator on community and environmental responsibility. The CEO expressed his pleasure with the results from this plan: “Our organization is aligned with its strategy. I know of no competitor that has this degree of alignment. It is producing results for us.”

Obviously, tying incentive compensation to scorecard measures is attractive, but it has some risks. Are the right measures on the scorecard? Are the data for the selected measures reliable? Could there be unintended or unexpected consequences in how the targets for the measures are achieved? The disadvantages occur when the initial scorecard measures are not perfect surrogates for the strategic objectives, and when the actions that improve the short-term measured results may be inconsistent with achieving the long-term objectives.

Figure 9-8

Incentive Compensation Based on the Balanced Scorecard

A second concern arises from the traditional mechanism for handling multiple objectives in a compensation function. This mechanism, as illustrated in the Pioneer Petroleum example, assigns weights to the individual objectives, with incentive compensation calculated by the percentage of achievement on each objective. This permits substantial incentive compensation to be paid even when performance is unbalanced; that is, the business unit overachieves on a few objectives, while falling far short on some others.

The Balanced Scorecard offers an alternative approach for determining when incentive compensation is paid. Corporate executives can establish minimum threshold levels across all, or a critical subset, of the strategic measures for the upcoming periods. Managers earn no incentive compensation if actual performance in a period falls short of the threshold on any of the designated measures. This constraint should motivate balanced performance across financial, customer, internal-business-process, and learning

and growth objectives. The threshold constraint should also balance short-term outcome measures and the performance drivers of future economic value. If the minimum thresholds are achieved on all measures, incentive compensation can be linked to outstanding performance across a smaller subset of measures. The subset used to determine the amount of incentive compensation will be the measures from the four perspectives felt to be most valuable for the organization to excel at in the upcoming period.

Some companies allow business unit managers to set their own targets for scorecard measures. But then the senior executive team makes a judgment about the degree of difficulty of the targets, and this degree of difficulty, analogous to how diving competitions are scored, influences the size of the bonus paid when targets are achieved. The senior executives use a combination of external benchmarking and subjective judgments to assess the stretch or slack in the unit managers’ targets.

Such use of subjective judgments reflects a belief that results-based compensation may not always be the ideal scheme for rewarding managers. Many factors not under the control or influence of managers also affect reported performance. Further, many managerial actions create (or destroy) economic value but may not be measured. Ideally, managers should be compensated for their abilities, their efforts, and the quality of their decisions and actions. Ability, effort, and decision quality are typically not used in formal compensation plans because of the difficulty of observing and measuring them. Pay-for-performance is a second-best approach, but one that is widely used because the other factors are so difficult to observe in practice.

Interestingly, the active use of the Balanced Scorecard provides much greater visibility about managerial abilities, efforts, and decision quality than traditional summary financial measures. The companies that, at least for the short run, abandon formula-based incentive systems often find that the dialogue among executives and managers about the scorecard—both the formulation of the objectives, measures, and targets, and the explanation of actual versus targeted results—provides many opportunities to observe managers’ performance and abilities. Consequently, even subjectively determined incentive rewards become easier and more defensible to administer. The subjective evaluations are also less susceptible to the game playing associated with explicit, formula-based rules.

A further consideration arises from the recognition that incentive compensation is an example of extrinsic motivation, in which individuals act

because they either have been told what to do, or because they will be rewarded for achieving certain clearly defined targets. Extrinsic motivation is important. Rewards and recognition should be associated with achieving business unit and corporate goals. But extrinsic motivation alone may be inadequate to encourage creative problem solving and innovative decision making. Several studies have found that intrinsic motivation, employees acting because of their personal preferences and beliefs, leads to more creative problem solving and innovation. In the context of the Balanced Scorecard, intrinsic motivation exists when employees’ personal goals and actions are consistent with achieving business unit objectives and measures. Intrinsically motivated individuals have internalized the organizational goals and strive to achieve those goals even when they are not explicitly tied to compensation incentives. In fact, explicit rewards may actually reduce or crowd out intrinsic motivation.

In several organizations, the clear articulation in a Balanced Scorecard of business unit strategic objectives, with links to associated performance drivers, has enabled many individuals to see, often for the first time, the links between what they do and the organization’s long-term objectives. Rather than behaving as automata, with bonuses tied to achieving or exceeding targets in the performance of their local tasks, individuals can now identify the tasks they should be doing exceptionally well to help achieve the organization’s objectives. This articulation of how individual tasks align with overall business unit objectives has created intrinsic motivation among large numbers of organizational employees. Their innovation and problem-solving energies have become unleashed, even without explicit ties to compensation incentives. Of course, since extrinsic motivation remains important, should the organization begin to achieve breakthrough performance by meeting or exceeding the stretch targets for its strategic measures, the employees who made such performance happen should be recognized and rewarded. Pioneer Petroleum, for example, has now implemented a variable compensation approach for all its nonunion employees, with rewards linked to achievement of business unit and company performance targets. Pioneer believes that tying compensation for the great majority of its employees to business unit scorecard measures has built deep organizational commitment to its strategic objectives.

In expressing caution about using Balanced Scorecard measures in formal compensation schemes, we do not advocate that such linkage not be used. The role of the scorecard in determining explicit rewards is still in its

embryonic stages. Clearly, attempting to gain organizational commitment to balanced performance across a broad set of leading and lagging indicators will be difficult if existing bonus and reward systems remain anchored to short-term financial results. At the very least, such short-term focus must be deemphasized.

Several approaches may be attractive to pursue. In the short term, tying incentive compensation of all senior managers to a balanced set of business unit scorecard measures will foster commitment to overall organizational goals, rather than suboptimization within functional departments. The dialogue that leads to formulation of the goals and the actions that help to achieve them will often reveal much about managerial ability and effort, enabling subjective judgments to be combined with quantitative outcome measures in calculating incentive compensation. Further experimentation and experience will provide additional evidence on the appropriate balance between explicit, objective formulas and subjective evaluation for linking incentive compensation to achievement of scorecard objectives.