The Bang-Bang Club (10 page)

Read The Bang-Bang Club Online

Authors: Greg Marinovich

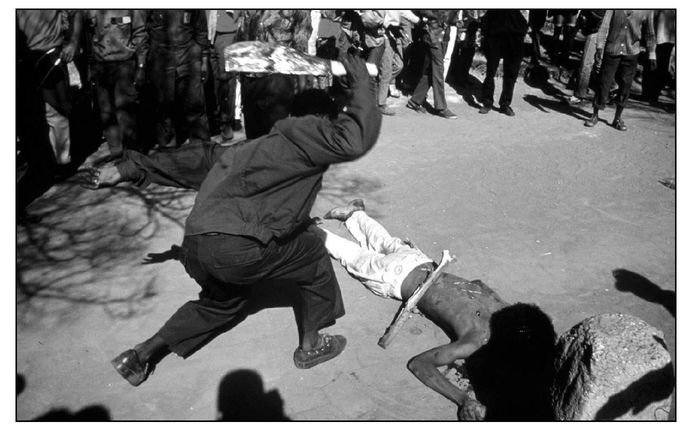

A resident of Boipatong hacks at the body of a Zulu man suspected of being an Inkatha member who had taken part in the Boipatong Massacre. He was later burned. (Joao Silva)

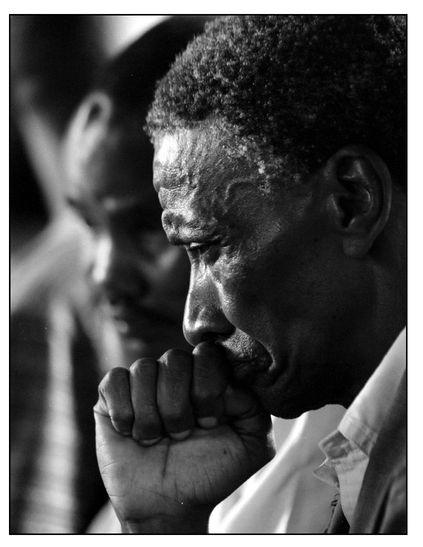

Daniel Sebolai, 64, who lost his wife and son in the Boipatong Massacre, holds back the tears during a workshop on issues related to the Truth & Reconciliation Commission in Sebokeng, 28 October, 1998. Next to him is Boy Samuel Makgome, 48, who lost his eye during an attack on a train by Inkatha Freedom Party members in 1992. Hundreds of victims who did not find sufficient or any redress from the commission are counselled and advised of their rights by nongovernmental self-help groups made up of human-rights victims. (Greg Marinovich)

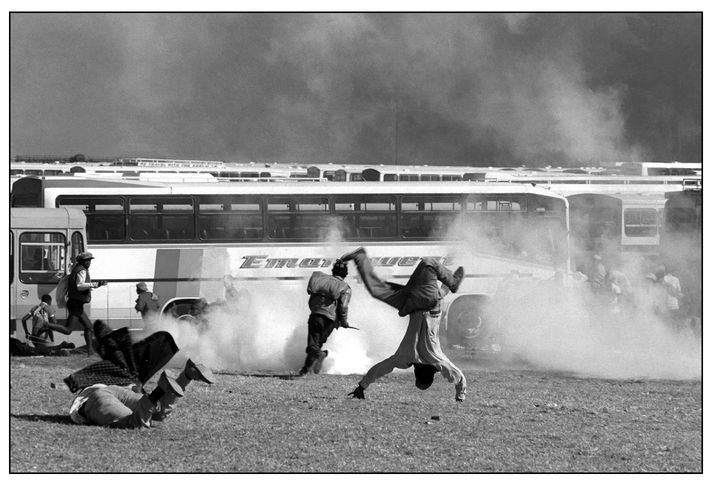

An ANC mourner takes evasive action from police gunfire during violent clashes at the funeral of Communist Party and ANC military leader, Chris Hani, 19 April, 1993. Hani was assassinated by white extremists. An election date for one year later was set soon afterwards. (Greg Marinovich)

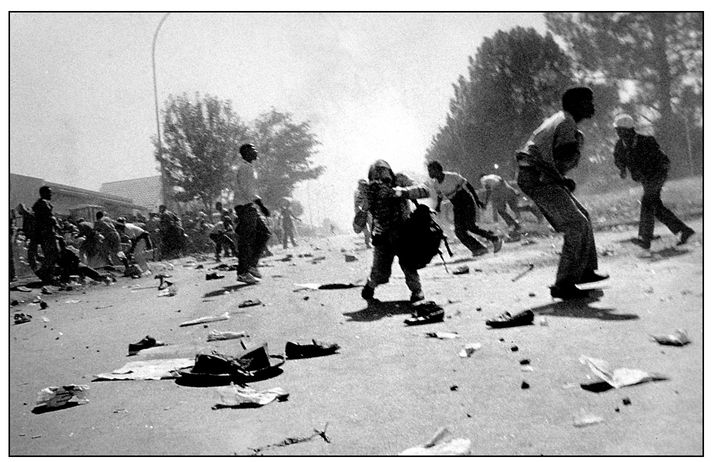

Kevin Carter aims his camera to take a picture of Ken Oosterbroek as Soweto residents flee police gunfire outside the Protea police station where they had been protesting after Chris Hani was assassinated by right-wing whites, April 1993. (Ken Oosterbroek /

The Star

)

The Star

)

From 1991 to 1993, South African political players were embroiled in protracted negotiations towards a transition to the ‘New South Africa’, and the ongoing violence was being used as a negotiating tool. It was impossible not to notice how the number of inexplicable massacres and attacks surged whenever the talks were at a critical stage. Even though we each in our own way were deeply motivated by the story, pictures and politics, cash also had its part in getting us up before the sun. The dawn was the transition between the chaos of the night and the occasional order of day - when the police would come in to collect the bodies.

I had become known as a conflict photographer. I could ask for assignments to almost any place, as long as people were killing each other. But it had taken me a while to learn how to make use of that reputation. When I had gone to New York in August of 1991 to collect the Pulitzer, I had asked if I had to wear a tux to the ceremony, not knowing that tuxes are not worn to lunchtime affairs. I also naïvely thought that the award would be a great opportunity to say something about what was happening back home. I spent days working on a speech and it was in my jacket pocket when my name was called and I walked up to the dias at Columbia University. But all the man did was shake my hand and give me a little crystal paperweight with Mr Pulitzer’s image engraved on it before ushering me away.

The other winners received their awards with equal haste and then there was a luncheon. It was the 75th anniversary of the prize and all living winners had been invited. It was an absurdly ideal place to establish contacts with many of the most important picture editors and the world’s greatest photographers. I made a wan effort to meet people, but I was in no frame of mind to do it effectively and left soon afterwards.

Despite my ineptitude in handling the business side of photography

and in marketing myself, by late September of 1991 I had convinced the AP to assign me to cover the war in Croatia, and within days I was in the front-line village of Nustar. It was autumn, cold and wet, and the roads had been churned into muddy trails by the tanks. It was my first time in a ‘real war’ with tanks, artillery and machine-guns. I had no clue of what was reasonably safe and what was insane, yet somehow I survived those first weeks without getting myself or anyone else killed. I found that I liked war. There was a peculiar, liberating excitement in taking cover from an artillery barrage in a woodshed that offered no protection at all. Two other journalists shared that particular woodshed with me: one was a young British photographer called Paul Jenks, who huddled in a steel wheelbarrow because it made him feel safer as the massive detonation of nearby shells mingled with the scream of others passing overhead. He would be killed months later by a Croat sniper’s bullet: Paul had come too close to discovering the cause of the death of another journalist who had been strangled by a member of a motley unit of international volunteers to the Croat army. My other companion was Heidi Rinke, an Austrian journalist with long black hair, beautiful green eyes and a wicked sense of humour. I lent her my flak jacket as she did not have one and so began a romance that would keep us warm through the long winter months of covering the Serbo-Croat war.

and in marketing myself, by late September of 1991 I had convinced the AP to assign me to cover the war in Croatia, and within days I was in the front-line village of Nustar. It was autumn, cold and wet, and the roads had been churned into muddy trails by the tanks. It was my first time in a ‘real war’ with tanks, artillery and machine-guns. I had no clue of what was reasonably safe and what was insane, yet somehow I survived those first weeks without getting myself or anyone else killed. I found that I liked war. There was a peculiar, liberating excitement in taking cover from an artillery barrage in a woodshed that offered no protection at all. Two other journalists shared that particular woodshed with me: one was a young British photographer called Paul Jenks, who huddled in a steel wheelbarrow because it made him feel safer as the massive detonation of nearby shells mingled with the scream of others passing overhead. He would be killed months later by a Croat sniper’s bullet: Paul had come too close to discovering the cause of the death of another journalist who had been strangled by a member of a motley unit of international volunteers to the Croat army. My other companion was Heidi Rinke, an Austrian journalist with long black hair, beautiful green eyes and a wicked sense of humour. I lent her my flak jacket as she did not have one and so began a romance that would keep us warm through the long winter months of covering the Serbo-Croat war.

Because of my Croat parentage, I spoke a passable pidgin Serbo-Croat and this sometimes gained me good access. So, in December of 1991, Heidi and I were the only journalists accompanying a troop of Croatian soldiers as they took village after village in the Papuk mountains. The Croats met only token resistance from geriatric villagers firing old hunting rifles at them, since the Yugoslav army and the Serb militia had already retreated, having seemingly decided that the area was bound to be lost sooner or later. It was eerie to see house after house burst into flames as we advanced on foot. In addition to putting Serb homes to the torch, many of the Croat soldiers were looting everything they could find, especially the local plum moonshine, slivovic. They also murdered many of the old folk who had been left behind. Deeper in the mountains, a soldier and I helped an old lady to the safety of her

neighbour’s farmhouse after her house had been torched. The Croat commander, a decent enough man in charge of a bunch of murderous drunks, promised that the women would be safe. A few hours later, I stopped by to check on them, but the barn and house had been burnt out. My heart was in my mouth as I searched for the two women. I found only one and she was lying dead in the frozen mud.

neighbour’s farmhouse after her house had been torched. The Croat commander, a decent enough man in charge of a bunch of murderous drunks, promised that the women would be safe. A few hours later, I stopped by to check on them, but the barn and house had been burnt out. My heart was in my mouth as I searched for the two women. I found only one and she was lying dead in the frozen mud.

In another hamlet, on another day, a conscience-stricken Croat soldier whispered to me that there was an old man still alive in one of the partially burnt farmhouses. Heidi and I tried to be nonchalant as we walked up the drive where blood spilled on the mud gave urgency to our search. We found nothing in the house, not even a corpse. I came back down to the road and surreptitiously asked the soldier where the wounded man was; he was terrified that his comrades would see him talking to me and whispered, ‘In the barn.’ I went back up past the blood and to the wooden barn, but saw only piles of hay. I started pulling at it, prepared for the worst; but I still got a fright when confronted by the grey, bloodless and unshaven face of an old man at the bottom of the pile. He was alive, but in a bad way. He had been shot and left under the hay to die. I tried to tell him to be calm, that we would get help. While Heidi was staunching the old peasant’s bleeding leg, I bent closer to hear what he was saying. I had my ear next to his mouth before I understood what it was that he kept repeating: ‘Don’t let the pigs eat my feet, don’t let the pigs eat my feet!’ It was not a crazy fear - pigs will eat anything, and on a few occasions I had seen pigs feeding off human corpses.

It was a strange war. One day I discovered a white-haired Serb lying dead in a ditch with his ears cut off. An unshaven, grinning Croat soldier with rotten teeth came up to me as I was taking pictures and he gleefully told me that he had killed and mutilated the old villager. His commander had a standing offer that anyone who brought him a pair of Serb ears could go home for four days. My Croatian surname allowed me to witness one side of the intimate brutalities of the civil war, but it precluded me from seeing the even greater toll of Serb atrocities up close.

Despite the horrors and my ancestral links to the country, the war did not have the same emotional impact on me as the events I had witnessed in South Africa - it was not my country and not my struggle. I was definitely there as a foreign journalist. In February of 1992, I returned to South Africa with Heidi. We lived together in the house I’d bought shortly after winning the Pulitzer. I had taken out a mortgage in order to buy it, as for the first time in my life I felt financially secure, after years of living hand-to-mouth. I was perpetually amazed by the turnaround in my circumstances - just one year previously I had been on the run from the police, but I now reckoned that there would be an outcry if they arrested South Africa’s only Pulitzer Prize-winner. I began to use my real name as a by-line. But in reality, the environment was changing, and ‘crimes’ such as mine were being ignored, as were draft-dodgers and conscientious objectors - whereas they had previously been hunted to ensure there was no ‘moral rot’ among whites. But even the Pulitzer could not change the effect that witnessing such searing events had had on me; on my return I found that I was almost immediately emotionally and politically ensnared by the events in South Africa. Unlike in the former Yugoslavia, I could not keep a distance from this story, nor from the people I photographed.

I remember a Sunday morning just weeks after coming back. In the street outside my house I was cleaning my car. Several neighbours also had hosepipes and buckets out as they cleaned and polished their cars - a Sunday ritual in my working-class neighbourhood. We greeted each other - they recognized me from interviews on television and in the papers. What they did not know was that I was not getting the car spruced up for the weekend, but that I was grimly trying to wash someone’s brains out of the cloth upholstery of my back seat. The previous afternoon, while most of South Africa was grilling meat on the braai or watching sport on television, I had been racing through the streets of Soweto trying to get to the hospital before the rasping, noisy breathing of the young man lying on my back seat ceased. The comrade’s girlfriend cradled his head in her lap and Heidi, sitting alongside, was telling me not to bother speeding, that it would make no

difference. Brain-matter and fluid bubbled freely out of a gunshot wound in his head and he was not going to make it. At the hospital they pronounced him dead.

difference. Brain-matter and fluid bubbled freely out of a gunshot wound in his head and he was not going to make it. At the hospital they pronounced him dead.

So, despite the cheery greetings from my neighbours, I resented them cleaning simple street dirt off their cars. This was something that I could not explain to them, nor to anyone else. It was as if they were occupying a different planet to me. It was precisely this that helped draw Joao, Ken, Kevin and me close to each other. When we tried to discuss those little telling details from incidents in the townships with people who had never experienced them, the usual response was either disgust or uncomprehending stares. We could only really talk about these matters to each other. Kevin had once written about his feelings on photography and covering conflict in an article which expressed thoughts that we had all, on occasion, shared: ‘I suffer depression from what I see and experience nightmares. I feel alienated from “normal” people, including my family. I find myself unable to relate to or engage in frivolous conversation. The shutters come down and I recede into a dark place with dark images of blood and death in godforsaken dusty places.’

Other books

01. Midnight At the Well of Souls by Jack L. Chalker

365 More Ways to Cook Chicken (365 ways) by Barnard, Melanie

Oaxaca Journal by Oliver Sacks, M.D.

Caged Heart by S. C. Edward

Bridle Path by Bonnie Bryant

Fields of Blue Flax by Sue Lawrence

The Orphan's Tale by Shaughnessy, Anne

Equal Affections by David Leavitt

Diary of a Naked Official by Ouyang Yu

Attic Clowns: Volume Four by Jeremy Shipp