The Battle of Hastings (9 page)

Read The Battle of Hastings Online

Authors: Jim Bradbury

The worst period of anxiety ended when Henry I of France came to his aid against the Norman rebels, enabling the young William to win his first major engagement at the battle of Val-ès-Dunes in 1047. The duke’s enemies gathered in the west of the duchy and advanced to the Orne, where their way was blocked by the duke’s supporters. The rebels broke, and many drowned in the river. If Wace is to be trusted, horses were seen running loose on the plain, while mounted men rode haphazardly in their efforts to escape. William of Poitiers confirms that riders drove their mounts into the Orne trying to get away, till the river was full of soldiers and horses.

36

The Conqueror’s main enemy and rival at this time had been Guy de Brionne, but the victory at Val-ès-Dunes crushed his ambitions. However, William showed little gratitude to the French king. Once freed from his greatest fears, he began to flex the muscles of his Norman war machine, and to attack neighbouring powers in a way that his predecessors had avoided. This caused growing resentment and hostility from those neighbours, and from the king.

We do not know the precise reasons, but it was in this context that the king of France joined the enemies of Normandy from 1052, and turned to attacking the duke he had previously defended. Possibly it was because of Norman participation in a rebellion against the king in the Ile-de-France. Whatever the reason, the king’s hostility added considerably to Normandy’s dangers in the mid-eleventh century.

37

William was equal to the new threat, and in the 1050s transformed Normandy into a greater military power. A serious problem was posed by the building of private castles during the worst of the disturbances. Now William had to spend much of his time besieging, destroying, or taking over these strongholds. Any rebel of standing could shelter behind the walls of his own castle. In the early part of the decade his own uncles, Count William of Arques and Mauger, Archbishop of Rouen, remained the greatest internal threats, and they could now look to assistance from France and the growing rival of Normandy, the county of Anjou.

Count William of Arques’ opposition turned into rebellion against his nephew by 1053. He had never readily accepted the succession of his brother’s illegitimate child. In 1053 Henry I of France tried to relieve Arques, but was beaten in a conflict at St-Aubin-sur-Scie by some of the Conqueror’s men, using a feigned flight. The surrender of Arques and the submission of Count William symbolise the triumph of the Conqueror over the rebels. His uncle was treated leniently and allowed to go into exile.

38

In 1054 the enemies of William combined in rebellion and invasion, but he thwarted their attack by a great victory at Mortemer. Here, according to William of Poitiers, the invading army was decimated. At midnight, William ordered a herald from the top of a tree to cry the details of the victory to the defeated king, who then fled.

39

One of the duke’s enemies in the field was the neighbouring Count Guy of Ponthieu. Guy was captured during the battle and submitted to the Conqueror, transferring allegiance to him. A few years later this move would have important consequences.

At this time, William was building a close group of familiars and friends from the Norman nobility, who would form a strong support to his activities throughout his life, men such as William fitz Osbern and Roger Montgomery, William de Warenne and Roger de Beaumont, together with his own half-brothers Robert, count of Mortain, and Odo, Bishop of Bayeux (sons of William’s mother, Herlève, by the husband Duke Robert had found for her). William II was beginning to take a grip on his duchy, and the great families and the lesser lords swung in behind his lead. He was also building a sound administration, revived after the period of troubles.

But William’s difficulties were far from over, and in 1057 he faced a new invasion from France and Anjou. The Angevin counts had expanded their territories in a manner even more remarkable than the successes to date of the Norman dukes. The Angevins had started from smaller beginnings, had no obvious frontiers to work towards, and were surrounded by hostile powers. At this time, Anjou was ruled by one of its greatest counts, Geoffrey Martel (1040–60). Normandy and Anjou were almost inevitably rivals since between them, and of interest to both, was the county of Maine, while both hoped to intervene also in Brittany.

William responded with energy to the new invasion and again defeated his enemies, this time at Varaville in 1057. Here William caught the invaders attempting to cross a ford on the River Dives, and attacked the rear section, when the change of the tide caused the river to rise. About half the enemy army had crossed and could not return. According to Wace, the Normans used archers and knights with lances to annihilate the men at their mercy.

40

Because of the tide, William was unable to pursue those on the far side, but Henry I was forced to flee from the duchy.

Even this victory did not ensure William’s triumph. Both the king of France and the count of Anjou had escaped and continued to oppose him with some success. It is sometimes overlooked that although William made claims upon Brittany and Maine, while Geoffrey Martel lived the latter was more successful.

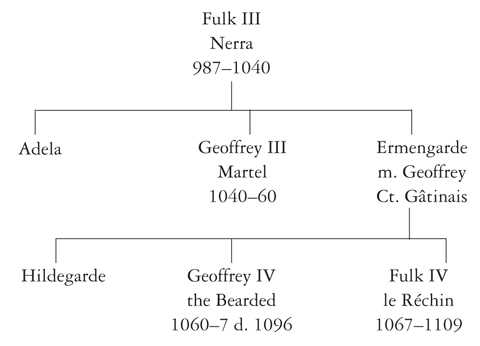

Counts of Anjou, 987–1109.

For William the year which brought great change and transformed his position and his hopes was 1060. His two greatest enemies died: Henry I of France, leaving an eight-year-old son, Philip I (1060–1108); and Geoffrey III Martel of Anjou, whose death resulted in a conflict between his nephews, Geoffrey IV the Bearded (1060–7, d. 1096) and Fulk IV le Réchin (1067–1109), to control the principality.

It was at this point that William could seriously undertake a programme of expansion beyond Normandy. However, even in 1060 his first concern was not with England, where any success must have still seemed a fairly distant likelihood. His first action was against Maine, situated on Normandy’s southern border. William captured the stronghold of his opponent, Geoffrey de Mayenne, by ‘throwing fire inside its walls’, and for a time from 1063 Maine fell under the power of Normandy.

41

Without Geoffrey Martel, Anjou went through a period of internal troubles from which William took advantage. In the following year he moved into the second area where Norman ambitions had been thwarted by Anjou and Brittany. This was the campaign in which Harold Godwinson took part.

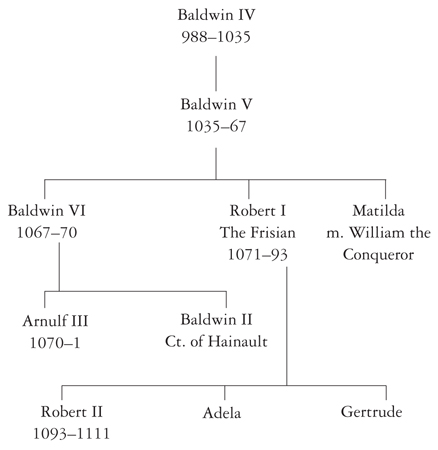

Counts of Flanders, 988–1111.

The reason why Harold went to Normandy is not clear. Edward the Confessor seems to have sent him, and at least one of his aims was to try and help two relatives who were hostages in Normandy. The Durham chronicler, perhaps rightly, claims that the trip was made at Harold’s initiative and against the king’s advice: he ‘begged the king’s permission to go to Normandy and liberate his brother and nephew, who were detained there as hostages, and to bring them back with him in freedom’.

42

William of Poitiers has William the Conqueror later in England claiming: ‘the king [Edward] gave me Godwin’s son and grandson as hostages. What is more, he sent Harold himself to Normandy, so that he might swear in person in my presence what his father and the others whom I have mentioned had sworn … he confirmed in writing that the kingship of England should without question be mine.’

43

There is a puzzle over this matter of the hostages. From the Norman sources they were handed over to guarantee Edward’s promise of the throne to William of Normandy, and it is difficult to think of an alternative reason. That then raises the question of why the hostages should be Harold’s younger brother, Wulfnoth, and his nephew, Hakon. The apparent answer would be to guarantee the Godwin family’s support for William. This in turn raises the question of the Godwin family’s attitude. It would surely have been impossible for Edward and William to arrange for such hostages without Harold’s consent. This would suggest that Harold favoured or at least accepted the idea of William’s succession.

If in 1064 Harold was seeking the release of the hostages, he could hardly obtain it without convincing William that he could trust in his support even without the hostages. This is conjectural, but it at least explains the nature of the oath. The probable explanation is that the Godwin interest in the throne through most of Edward’s reign was not in seeking it for themselves, but in ensuring that, whoever came to the throne, the Godwin position would be secure. They were therefore not especially opposed to either Edgar the Aetheling or William, if their own family position was guaranteed.

The Tapestry shows Harold setting off in a leisurely manner, perhaps hunting on the way. He rested at his own manor of Bosham, where he feasted before boarding ship in Chichester Harbour. It was probably a storm which blew him to the shores of Ponthieu where he was arrested by Count Guy and taken to his castle at Beaurain. What Guy hoped to gain is uncertain, perhaps to use Harold as a bargaining counter with William.

The Conqueror was informed of the event, and ordered Harold’s release. Count Guy was no great friend of the Norman duke, but he had been forced into recognising his overlordship after being among the defeated at Varaville. At any rate, Guy decided not to oppose William and escorted the captive to the duke, to whom he was handed. The act of obtaining his release gave William an advantage over Harold, whose ability to act freely in Normandy is uncertain.

William received Harold in the palace at Rouen. The Tapestry refers to some now forgotten scandal there between a woman with an English name, Aelfgyva, and a cleric, and then shows William setting off with Harold on the Breton campaign.

44

They passed by the great coastal monastery of Mont-St-Michel. Crossing the River Couesnon some of the Norman soldiers got into trouble in the quicksand, and were saved by the heroic action of Harold.

Their first objective was the castle at Dol, which the Tapestry shows as a wooden keep on a mound, a motte. It also shows Conan II, count of Brittany, escaping down a rope, though chronicle sources tell us that he had gone before the Normans arrived. They took Rennes and moved on to Dinan, which resisted. These two castles are also portrayed as wooden towers on mottes. Dinan was fired with torches, and the Bretons handed over the keys in surrender.

The Breton campaign had been successful, though its effects were soon to be reversed. William recognised the English earl’s contribution, and ‘gave arms to Harold’.

45

The Tapestry version is surely the portrayal of a knighting ceremony. It probably means that Harold recognised William as his lord, and must be taken along with the oath in defining how the Normans viewed Harold’s subsequent actions.

So the victorious Norman army, having temporarily imposed its authority on eastern Brittany, rode back to Bayeux, where William’s half-brother, Odo, was bishop. It was here, according to the Tapestry, that Harold took the famous oath to William.

46

Chronicle reports say it took place earlier and elsewhere, and Bonneville-sur-Touques, which is named for the event by William of Poitiers, is the most likely location. The Tapestry, in naming Bayeux, may have been trying to puff up the role of Bishop Odo, for whom the English artist was probably working.

There can be little doubt that an oath was made. What its exact content was we shall never know. Nor can we be quite certain if Harold was forced or tricked into swearing. The Norman interpretation was that Harold had made a promise to support William, perhaps as his man. William of Jumièges says that Edward sent Harold to ‘swear fealty to the duke concerning his crown and, according to the Christian custom, pledge it with oaths’. William of Poitiers confirms this, saying that Harold promised to do all in his power to ensure William’s succession to the English throne. He goes on to say that Harold promised to hand Dover to William with various other strongholds in England. We cannot take the Norman view without retaining some doubts about its accuracy on the detail, but it is impossible to discount the oath altogether, and William’s actions throughout point to his belief that in 1066 Harold betrayed his trust.

47