The Beasts that Hide from Man (22 page)

Read The Beasts that Hide from Man Online

Authors: Karl P.N. Shuker

During the early 17th century, scholar Charles de l’Ecluse placed on record the eventful history of the first cassowary ever seen in Europe — a much-traveled specimen originally captured on the Moluccan island of Seram (Ceram), but brought back to Amsterdam in 1597 from Banda (another Moluccan island) by the first Dutch expedition to the East Indies. Given to the expedition by the ruler of the Javanese town of Lydajo, it lost no time in becoming a much-coveted cassowary following its arrival in Holland. Effortlessly ascending ever higher through the rarefied strata of European high society, after a period of several months as the star of a highly successful public exhibition at Amsterdam, this distinguished bird passed into the hands of the Count of Solms and journeyed to the Hague. Later it was owned for a time by the Elector Palatine, before attaining the zenith of its fame by becoming the property of no less a personage than Emperor Rudolph II of the Holy Roman Empire.

Its species became known as

Casuarius casuarius

, and is the tallest of the three modern-day species of cassowary averaging five and a half feet in height (including its lofty casque), and generally sporting two wattles on its neck, so that it is most commonly called the double-wattled cassowary. Based in most cases upon only the most trivial of differences in the color, number, and shape of these wattles, a bewildering plethora of species all supposedly distinct from C.

casuarius

were described during the 19th century. These included C.

australis

(from northeastern Australia), C.

beccarii

and C.

bicarunculatus

(both from the Am Islands), C.

tricarunculatus

(Geelvink Bay), and C.

unappendiculatus

(Salawati Island).

Only the last-mentioned of these, however, is still recognized as a genuinely separate species. Standing four and a half feet to five feet tall and known as the single-wattled cassowary, C.

unappendiculatus

also inhabits New Guinea and the offshore islands of Misol and Japen. It was first made known to science by Edward Blyth in 1860, from a specimen brought back alive to Calcutta from an unrecorded locality.

Three years earlier, Dr. George Bennett, a surgeon and biologist from New South Wales, had recorded the existence on New Britain of a cassowary whose unusually small size, lack of wattles, and noticeably flattened casque left no room for doubt that, unlike so many other forms being described and named, this really was a radically new, well-delineated species. Known to the natives as the

mooruk

and only three and a half feet tall, it was later christened C.

bennetti

, Bennett’s cassowary, by John Gould. Greatly intrigued by this dwarf species, Bennett obtained two

mooruks

from New Britain and gave them the freedom of his home—discovering that they made entertaining if inquisitive house guests, as succinctly summarized in W. H. Davenport Adams’s

The Bird World

(1885):

The birds…were very tame; they ran freely about his house and garden—fearlessly approaching any person who was in the habit of feeding them. After a while they grew so bold as to disturb the servants while at work; they entered the open doors, followed the inmates step by step, pried and peered into every corner of the kitchen, leaped upon the chairs and tables, flocked round the busy and bountiful cook. If an attempt were made to catch them, they immediately took to flight, hid under or among the furniture, and lustily defended themselves with beak and claw. But as soon as they were left alone they returned, of their own accord, to their accustomed place. If a servant-maid endeavoured to drive them away, they struck her and rent her garments. They would penetrate into the stables among the horses, and eat with them, quite sociably, out of the rack. Frequently they pushed open the door of Bennett’s study, walked all around it gravely and quietly, examined every article, and returned as noiselessly as they came.

The discovery of Bennett’s cassowary was followed by the documentation of other, similarly undersized, wattle-less types, initially treated as distinct species. These included Westermann’s cassowary C.

westermanni

(Jobi Island) and the painted cassowary C.

picticollis

(southeastern New Guinea), but they are all conspecific with C.

bennetti

.

Among the wealth of myth and folklore associated with cassowaries is a most curious conviction fostered by such tribes as the Huri and the Wola from Papua New Guinea’s remote Southern Highlands Province. According to their lore, a female Bennett’s cassowary maintained in captivity is able to reproduce even if she is not provided with a male partner. All that she has to do is locate a specific type of tree and thrust her breast against its trunk, again and again, in an ever-intensifying frenzy, until at last she collapses onto the floor in a state of complete exhaustion, suffering from internal bleeding that festers and clots to yield yellow pus. This in turn proliferates, producing yolk-containing eggs that the female lays, and which are incubated and hatch as normal.

Although a highly bizarre tale, it is worth recalling that cases of parthenogenesis (virgin birth) are fully confirmed from a few species of bird, notably the common turkey; the offspring are genetically identical to their mother. Perhaps, therefore, this odd snippet of native folklore should be investigated—just in case (once such evident elements of fantasy as the pus-engendered yolk are stripped away) there is a foundation in fact for it, still awaiting scientific disclosure.

An even more imaginative Wola belief regarding Bennett’s cassowary concerns its migratory habits. As revealed by Paul Sillitoe during a filming expedition to Wola territory in 1978

(Geographical Journal

, May 1981), these birds only visit this area when the fruits upon which they feed are in season here. At the season’s end they travel further afield again, but the Wola are convinced that they have gone to live in the sky with a thunder goddess (though they neglect to reveal how these flightless birds become airborne!).

Irrespective of these charming tales, it is true that for flightless birds the cassowaries do exhibit an extraordinarily dispersed, far-flung distribution—occurring on a surprising number of different islands. Admittedly, many of these islands were once joined to one another in the not-too-distant geological past, but some ornithologists remain doubtful that the cassowaries’ range is natural—suggesting instead that they may have been introduced onto certain of their insular territories by humans. For example, Drs. A.L. Rand and Thomas Gilliard proposed in their

Handbook of New Guinea Birds

(1967) that C.

casuarius

may well have been brought by man to Seram. In view of the New Guinea tribes’ very extensive trade in cassowaries—not only transporting them across land but also exporting them far and wide in boats, a tradition known to have been occurring for at least 500 years, such a possibility is by no means implausible. It was raised in 1975 by Dr. C.M.N. White too, within the British Ornithologists Club’s bulletin, and he offered a corresponding explanation in the same publication the following year for the presence on New Britain of Bennett’s cassowary.

Probably the most unexpected variation on the theme of displaced cassowaries, however, is a case aired by Drs. G.H. Ralph von Koenigswald and Joachim Steinbacher

(Natur und Museum

, 1986), who reported the presence of a bas-relief depiction of a readily identifiable cassowary upon a temple near Wadjak in eastern Java. As there is no evidence to imply that Java ever harbored a native form of cassowary, this depiction lends itself to a variety of different cultural interpretations. For example, it suggests that the centuries-old tradition of cassowary trade and export from New Guinea even extended as far afield as Java—the ownership of one such bird by the ruler of Lydajo, Java, in 1597 bolsters this hypothesis. Alternatively, the depiction might simply have been based upon

descriptions

of cassowaries, recounted to the Javan natives by visiting New Guinea traders. There is even the chance that the Javan tribe responsible for this painting was descended from one that had migrated to southeast Asia from New Guinea, and the picture was inspired by orally preserved traditions among this translocated people of birds known to their ancestors in New Guinea.

Incidentally, comparable hypotheses to those outlined above for the “Javan cassowary/’ but this time featuring travelers or ancestors from New Zealand rather than from New Guinea, could also explain the moa-like bird depicted upon the 800-year-old principal temple of Angkor in Cambodia—another iconographical oddity unfurled by von Koenigswald and Steinbacher in their paper.

GERONTICUS

The famous Greek legend featuring Heracles and the dreaded Stymphalian birds. A non-existent forest raven native to the lofty peaks of the Swiss Alps. The epic biblical story of Noah and the Great Flood. What conceivable connection could exist between such ostensibly disparate subjects as these? The answer is a genuine

rara avis

called

Geronticus

—a baffling bird encompassed by all manner of myths and mysteries, drawn together from the dreams of the past.

One of the twelve great labors imposed upon the mighty Greek hero Heracles by the cowardly King Eurystheus of Argolis was to vanquish the Stymphalides—a flock of brass-winged, crane-sized, ibis-like birds with crests and a craving for human flesh, which frequented the Stymphalian marshes in Arcadia. With the aid of a loudly resonating pair of brass rattles forged by the fire god Hephaestus and loaned to him by the war goddess Athena, however, Heracles was able to scare the birds out of their marshy domain and into flight. Once they were airborne, wheeling overhead in a frenzy of fright engendered by the ear-splitting cacophony of the rattles, he then proceeded to fire volley after volley of arrows into their soft, unprotected bellies, killing some and sending the remainder flying far away toward the Black Sea, never to return to Arcadia.

These fearful bird-monsters were originally thought to constitute an imaginative personification of marsh fever, but in 1987 Swiss ornithologist Michael Desfayes proposed that they may actually have been based upon a real (albeit smaller, harmless) bird.

Also called the hermit ibis, the waldrapp

Geronticus eremita

is a very rare relative of the more familiar sacred ibis of Egypt and South America’s scarlet ibis, and sports a crest, a long red beak, and bronze-colored wings. It is nowadays restricted to a scattering of sites in Morocco and Algeria, and one notable locality in Turkey— its only toehold in Europe. However, it was once much more widespread, known from as far west as Germany, Austria, and Switzerland (see below). Moreover, after comparing its morphology with classic descriptions of the Stymphalides, Desfayes opined that they were one and the same species, and that Greece should thus be added to the waldrapp’s former distribution range.

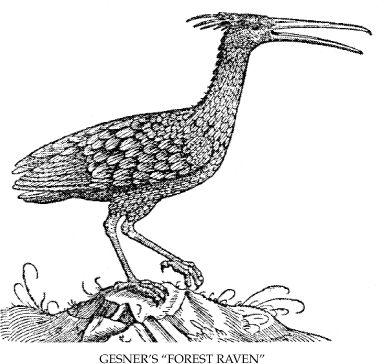

Another longstanding mystery bird from Europe was the Swiss forest raven described and portrayed by Zurich scholar Conrad Gesner in his

Historiae Animalium

, published in 1555. Later writers dismissed this bird as imaginary, because it seemed to resemble a crested ibis rather than a raven, and there was no ibislike bird known from Switzerland. Not until 1941 was the mystery finally resolved, when geologically Recent remains of waldrapps were excavated from the Glarus Alps and sites near Solothurn.

This distinctive bird corresponds perfectly with Gesner’s description and depiction of his perplexing “forest raven/’ and it is now known that way back in 1504 the waldrapp was formally designated a protected species in the Alps by Archbishop Leonard of Salzburg. Tragically, however, his decree was largely ignored, and the waldrapp’s nestlings were hunted mercilessly as prized culinary delicacies. Less than a century later it had become extinct here, swiftly fading from memory and ultimately transforming into an apparently mythical, non-existent bird known only from a medieval bestiary.

It is likely that the waldrapp would have become extinct in Turkey too, but here it has been saved not only by modern conservationist zeal but also by traditional religious belief. According to ancient Turkish lore, the waldrapp was one of the birds released by Noah after the Great Flood, and symbolizes fertility—giving the people of Birecik, site of this species’ only notable Turkish colony, an added incentive for perpetuating its tenuous survival here.

The Torres Strait separates New Guinea from the northernmost tip of Queensland, and contains many tiny, virtually unexplored islets. According to the 19th century naturalist Luigi d’Albertis, among others, one of these houses a huge species of hornbill, known as the

kusa kap

. The largest

known

species include the familiar great Indian hornbill

Buceros bicornis

and the rhinoceros hornbill

B. rhinoceros

(from Malaysia, the Sundas, and Borneo), both of which can attain a total length of four feet, but these pale into insignificance alongside the

kusa kap

—whose alleged 22-foot wingspan, not to mention its inclination for carrying dugongs aloft in its claws, more closely recall the legendary elephant-transporting roc! Moreover, the noise of its wings flapping in flight is said to resemble the roar of a steam engine!