The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (141 page)

Read The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Tags: #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Amazon.com, #21st Century, #Crime, #Anthropology, #Social History, #Retail, #Criminology

BOOK: The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

2.41Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

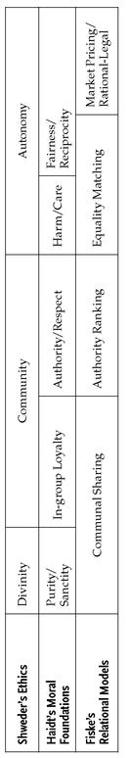

Shweder organized the world’s moral concerns in a threefold way.

171

Autonomy, the ethic we recognize in the modern West, assumes that the social world is composed of individuals and that the purpose of morality is to allow them to exercise their choices and to protect them from harm. The ethic of Community, in contrast, sees the social world as a collection of tribes, clans, families, institutions, guilds, and other coalitions, and equates morality with duty, respect, loyalty, and interdependence. The ethic of Divinity posits that the world is composed of a divine essence, portions of which are housed in bodies, and that the purpose of morality is to protect this spirit from degradation and contamination. If a body is merely a container for the soul, which ultimately belongs to or is part of a god, then people do not have the right to do what they want with their bodies. They are obligated to avoid polluting them by refraining from unclean forms of sex, food, and other physical pleasures. The ethic of Divinity lies behind the moralization of disgust and the valorization of purity and asceticism.

171

Autonomy, the ethic we recognize in the modern West, assumes that the social world is composed of individuals and that the purpose of morality is to allow them to exercise their choices and to protect them from harm. The ethic of Community, in contrast, sees the social world as a collection of tribes, clans, families, institutions, guilds, and other coalitions, and equates morality with duty, respect, loyalty, and interdependence. The ethic of Divinity posits that the world is composed of a divine essence, portions of which are housed in bodies, and that the purpose of morality is to protect this spirit from degradation and contamination. If a body is merely a container for the soul, which ultimately belongs to or is part of a god, then people do not have the right to do what they want with their bodies. They are obligated to avoid polluting them by refraining from unclean forms of sex, food, and other physical pleasures. The ethic of Divinity lies behind the moralization of disgust and the valorization of purity and asceticism.

Haidt took Shweder’s trichotomy and cleaved two of the ethics in two, yielding a total of five concerns that he called moral foundations.

172

Community was bifurcated into In-group Loyalty and Authority/Respect

,

and Autonomy was sundered into Fairness/Reciprocity (the morality behind reciprocal altruism) and Harm/Care (the cultivation of kindness and compassion, and the inhibition of cruelty and aggression). Haidt also gave Divinity the more secular label Purity/Sanctity

.

In addition to these adjustments, Haidt beefed up the case that the moral foundations are universal by showing that all five spheres may be found in the moral intuitions of secular Westerners. In his dumbfounding scenarios, for example, Purity/Sanctity underlay the participants’ revulsion to incest, bestiality, and the eating of a family pet. Authority/ Respect commanded them to visit a mother’s grave. And In-group Loyalty prohibited them from desecrating an American flag.

172

Community was bifurcated into In-group Loyalty and Authority/Respect

,

and Autonomy was sundered into Fairness/Reciprocity (the morality behind reciprocal altruism) and Harm/Care (the cultivation of kindness and compassion, and the inhibition of cruelty and aggression). Haidt also gave Divinity the more secular label Purity/Sanctity

.

In addition to these adjustments, Haidt beefed up the case that the moral foundations are universal by showing that all five spheres may be found in the moral intuitions of secular Westerners. In his dumbfounding scenarios, for example, Purity/Sanctity underlay the participants’ revulsion to incest, bestiality, and the eating of a family pet. Authority/ Respect commanded them to visit a mother’s grave. And In-group Loyalty prohibited them from desecrating an American flag.

The system I find most useful was developed by the anthropologist Alan Fiske. It proposes that moralization comes out of four relational models, each a distinct way in which people conceive of their relationships.

173

The theory aims to explain how people in a given society apportion resources, where their moral obsessions came from in our evolutionary history, how morality varies across societies, and how people can compartmentalize their morality and protect it with taboos. The relational models line up with the classifications of Shweder and Haidt more or less as shown in the table on page 626.

173

The theory aims to explain how people in a given society apportion resources, where their moral obsessions came from in our evolutionary history, how morality varies across societies, and how people can compartmentalize their morality and protect it with taboos. The relational models line up with the classifications of Shweder and Haidt more or less as shown in the table on page 626.

The first model, Communal Sharing (Communality for short), combines In-group Loyalty with Purity/Sanctity. When people adopt the mindset of Communality, they freely share resources within the group, keeping no tabs on who gives or takes how much. They conceptualize the group as “one flesh,” unified by a common essence, which must be safeguarded against contamination. They reinforce the intuition of unity with rituals of bonding and merging such as bodily contact, commensal meals, synchronized movement, chanting or praying in unison, shared emotional experiences, common bodily ornamentation or mutilation, and the mingling of bodily fluids in nursing, sex, and blood rituals. They also rationalize it with myths of shared ancestry, descent from a patriarch, rootedness in a territory, or relatedness to a totemic animal. Communality evolved from maternal care, kin selection, and mutualism, and it may be implemented in the brain, at least in part, by the oxytocin system.

Fiske’s second relational model, Authority Ranking, is a linear hierarchy defined by dominance, status, age, gender, size, strength, wealth, or precedence. It entitles superiors to take what they want and to receive tribute from inferiors, and to command their obedience and loyalty. It also obligates them to a paternalistic, pastoral, or noblesse oblige responsibility to protect those under them. Presumably it evolved from primate dominance hierarchies, and it may be implemented, in part, by testosterone-sensitive circuits in the brain.

Equality Matching embraces tit-for-tat reciprocity and other schemes to divide resources equitably, such as turn-taking, coin-flipping, matching contributions, division into equal portions, and verbal formulas like eeny-meenyminey-moe. Few animals engage in clear-cut reciprocity, though chimpanzees have a rudimentary sense of fairness, at least when it comes to themselves being shortchanged. The neural bases of Equality Matching embrace the parts of the brain that register intentions, cheating, conflict, perspective-taking, and calculation, which include the insula, orbital cortex, cingulate cortex, dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, parietal cortex, and temporoparietal junction. Equality Matching is the basis of our sense of fairness and our intuitive economics, and it binds us as neighbors, colleagues, acquaintances, and trading partners rather than as bosom buddies or brothers-in-arms. Many traditional tribes engaged in the ritual exchange of useless gifts, a bit like our Christmas fruitcakes, solely to cement Equality Matching relationships.

174

174

(Readers who are comparing and contrasting the taxonomies may wonder why Haidt’s category of Harm/Care is adjacent to Fairness and aligned with Fiske’s Equality Matching, rather than with more touchy-feely relationships like Community or Sanctity. The reason is that Haidt measures Harm/Care by asking people about the treatment of a generic “someone” rather than the friends and relatives that are the standard beneficiaries of caring. The responses to these questions align perfectly with the responses to his questions about Fairness, and that is no coincidence.

175

Recall that the logic of reciprocal altruism, which implements our sense of fairness, is to be “nice” by cooperating on the first move, by not defecting unless defected on, and by conferring a large benefit to a needy stranger when one can do so at a relatively small cost to oneself. When care and harm are extended outside intimate circles, then they are simply a part of the logic of fairness.)

176

175

Recall that the logic of reciprocal altruism, which implements our sense of fairness, is to be “nice” by cooperating on the first move, by not defecting unless defected on, and by conferring a large benefit to a needy stranger when one can do so at a relatively small cost to oneself. When care and harm are extended outside intimate circles, then they are simply a part of the logic of fairness.)

176

Fiske’s final relational model is Market Pricing: the system of currency, prices, rents, salaries, benefits, interest, credit, and derivatives that powers a modern economy. Market Pricing depends on numbers, mathematical formulas, accounting, digital transfers, and the language of formal contracts. Unlike the other three relational models, Market Pricing is nowhere near universal, since it depends on literacy, numeracy, and other recently invented information technologies. The logic of Market Pricing remains cognitively unnatural as well, as we saw in the widespread resistance to interest and profits until the modern era. One can line up the models, Fiske notes, along a scale that more or less reflects their order of emergence in evolution, child development, and history: Communal Sharing > Authority Ranking > Equality Matching > Market Pricing.

Market Pricing, it seems to me, is specific neither to markets nor to pricing. It really should be lumped with other examples of formal social organization that have been honed over the centuries as a good way for millions of people to manage their affairs in a technologically advanced society, but which may not occur spontaneously to untutored minds.

177

One of these institutions is the political apparatus of democracy, where power is assigned not to a strongman (Authority) but to representatives who are selected by a formal voting procedure and whose prerogatives are delineated by a system of laws. Another is a corporation, university, or nonprofit organization. The people who work in them aren’t free to hire their friends and relations (Communality) or to dole out spoils as favors (Equality Matching), but are hemmed in by fiduciary duties and regulations. My emendation of Fiske’s theory does not come out of the blue. Fiske notes that one of his intellectual inspirations for Market Pricing was the sociologist Max Weber’s concept of a “rational-legal” (as opposed to traditional and charismatic) mode of social legitimation—a system of norms that is worked out by reason and implemented by formal rules.

178

Accordingly, I will sometimes refer to this relational model using the more general term Rational-Legal.

177

One of these institutions is the political apparatus of democracy, where power is assigned not to a strongman (Authority) but to representatives who are selected by a formal voting procedure and whose prerogatives are delineated by a system of laws. Another is a corporation, university, or nonprofit organization. The people who work in them aren’t free to hire their friends and relations (Communality) or to dole out spoils as favors (Equality Matching), but are hemmed in by fiduciary duties and regulations. My emendation of Fiske’s theory does not come out of the blue. Fiske notes that one of his intellectual inspirations for Market Pricing was the sociologist Max Weber’s concept of a “rational-legal” (as opposed to traditional and charismatic) mode of social legitimation—a system of norms that is worked out by reason and implemented by formal rules.

178

Accordingly, I will sometimes refer to this relational model using the more general term Rational-Legal.

For all their differences in lumping and splitting, the theories of Shweder, Haidt, and Fiske agree on how the moral sense works. No society defines everyday virtue and wrongdoing by the Golden Rule or the Categorical Imperative. Instead, morality consists in respecting or violating one of the relational models (or ethics or foundations): betraying, exploiting, or subverting a coalition; contaminating oneself or one’s community; defying or insulting a legitimate authority; harming someone without provocation; taking a benefit without paying the cost; peculating funds or abusing prerogatives.

The point of these taxonomies is not to pigeonhole entire societies but to provide a grammar for social norms.

179

The grammar should reveal common patterns beneath the differences among cultures and periods (including the decline of violence), and should predict people’s response to infractions of the reigning norms, including their perverse genius for moral compartmentalization.

179

The grammar should reveal common patterns beneath the differences among cultures and periods (including the decline of violence), and should predict people’s response to infractions of the reigning norms, including their perverse genius for moral compartmentalization.

Some social norms are merely solutions to coordination games, such as driving on the right-hand side of the road, using paper currency, and speaking the ambient language.

180

But most norms have moral content. Each moralized norm is a compartment containing a relational model, one or more social roles (parent, child, teacher, student, husband, wife, supervisor, employee, customer, neighbor, stranger), a context (home, street, school, workplace), and a resource (food, money, land, housing, time, advice, sex, labor). To be a socially competent member of a culture is to have assimilated a large set of these norms.

180

But most norms have moral content. Each moralized norm is a compartment containing a relational model, one or more social roles (parent, child, teacher, student, husband, wife, supervisor, employee, customer, neighbor, stranger), a context (home, street, school, workplace), and a resource (food, money, land, housing, time, advice, sex, labor). To be a socially competent member of a culture is to have assimilated a large set of these norms.

Take friendship. Couples who are close friends operate mainly on the model of Communal Sharing. They freely share food at a dinner party, and they do each other favors without keeping score. But they may also recognize special circumstances that call for some other relational model. They may work together on a task in which one is an expert and gives orders to the other (Authority Ranking), split the cost of gas on a trip (Equality Matching), or transact the sale of a car at its blue book value (Market Pricing).

Infractions of a relational model are moralized as straightforwardly wrong. Within the Communal Sharing model that usually governs a friendship, it is wrong for one person to stint on sharing. Within the special case of Equality Matching of gas on a trip, an infraction consists of failing to pay for one’s share. Equality Matching, with its assumption of a continuing reciprocal relationship, allows for loose accounting, as when the ranchers of Shasta County compensated each other for damage with roughly equivalent favors and agreed to lump it when a small act of damage went uncompensated.

181

Market Pricing and other Rational-Legal models are less forgiving. A diner who leaves an expensive restaurant without paying cannot count on the owner to let him make it up in the long run, or simply to lump it. The owner is more likely to call the police.

181

Market Pricing and other Rational-Legal models are less forgiving. A diner who leaves an expensive restaurant without paying cannot count on the owner to let him make it up in the long run, or simply to lump it. The owner is more likely to call the police.

When a person violates the terms of a relational model he or she has tacitly agreed to, the violator is seen as a parasite or cheater and becomes a target of moralistic anger. But when a person applies one relational model to a resource ordinarily governed by another, a different psychology comes into play. That person doesn’t violate the rules so much as he or she doesn’t “get” them. The reaction can range from puzzlement, embarrassment, and awkwardness to shock, offense, and rage.

182

Imagine, for example, a diner thanking a restaurateur for an enjoyable experience and offering to have him over for dinner at some point in the future (treating a Market Pricing interaction as if it were governed by Communal Sharing). Conversely, imagine the reaction at a dinner party (Communal Sharing) if a guest pulled out his wallet and offered to pay the host for the meal (Market Pricing), or if the host asked a guest to wash the pots while the host relaxed in front of the television (Equality Matching). Likewise, imagine that the guest offered to sell his car to the host, and then drove a hard bargain on the price, or the host suggested that the couples swap partners for a half-hour of sex before everyone went home for the evening.

182

Imagine, for example, a diner thanking a restaurateur for an enjoyable experience and offering to have him over for dinner at some point in the future (treating a Market Pricing interaction as if it were governed by Communal Sharing). Conversely, imagine the reaction at a dinner party (Communal Sharing) if a guest pulled out his wallet and offered to pay the host for the meal (Market Pricing), or if the host asked a guest to wash the pots while the host relaxed in front of the television (Equality Matching). Likewise, imagine that the guest offered to sell his car to the host, and then drove a hard bargain on the price, or the host suggested that the couples swap partners for a half-hour of sex before everyone went home for the evening.

Other books

The Farwalker's Quest by Joni Sensel

Teetoncey and Ben O'Neal by Theodore Taylor

Drummer Girl by Karen Bass

The Man In The Wind by Wise, Sorenna

The Choice - A Small Town Love Triangle by Phoenix, Piper

City of the Cyborgs by Gilbert L. Morris

Breakfast at Tiffany’s by Ann Cory

Married Woman by Manju Kapur

Dancer in the Shadows by Wisdom, Linda

Billi Jean by Running Scared