The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined (68 page)

Read The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined Online

Authors: Steven Pinker

Tags: #Sociology, #Psychology, #Science, #Amazon.com, #21st Century, #Crime, #Anthropology, #Social History, #Retail, #Criminology

BOOK: The Better Angels of Our Nature: Why Violence Has Declined

12Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

The Long Peace—an avoidance of major war among great powers and developed states—is spreading to the rest of the world. Aspiring great powers no longer feel the need to establish their greatness by acquiring an empire or picking on weaker countries: China boasts of its “peaceful rise” and Turkey of a policy it calls “zero problems with neighbors”; Brazil’s foreign minister recently crowed, “I don’t think there are many countries that can boast that they have 10 neighbors and haven’t had a war in the last 140 years.”

24

And East Asia seems to be catching Europe’s distaste for war. Though in the decades after World War II it was the world’s bloodiest region, with ruinous wars in China, Korea, and Indochina, from 1980 to 1993 the number of conflicts and their toll in battle deaths plummeted, and they have remained at historically unprecedented lows ever since.

25

24

And East Asia seems to be catching Europe’s distaste for war. Though in the decades after World War II it was the world’s bloodiest region, with ruinous wars in China, Korea, and Indochina, from 1980 to 1993 the number of conflicts and their toll in battle deaths plummeted, and they have remained at historically unprecedented lows ever since.

25

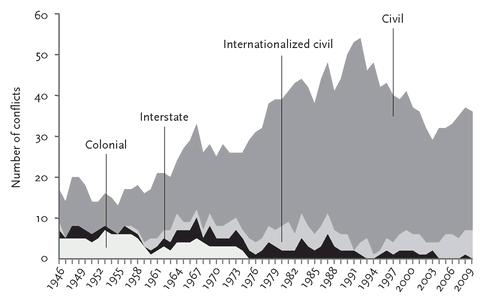

As interstate war was being snuffed out, though, civil wars began to flare up. We see this in the enormous dark gray wedge at the left of figure 6–2, mainly representing the 1.2 million battle deaths in the 1946–50 Chinese Civil War, and a fat lighter gray bulge at the top of the stack in the 1980s, which contains the 435,000 battle deaths in the Soviet Union–bolstered civil war in Afghanistan. And snaking its way through the 1980s and 1990s, we find a continuation of the dark gray layer with a mass of smaller civil wars in countries such as Angola, Bosnia, Chechnya, Croatia, El Salvador, Ethiopia, Guatemala, Iraq, Liberia, Mozambique, Somalia, Sudan, Tajikistan, and Uganda. But even this slice tapers down in the 2000s to a slender layer.

To get a clearer picture of what the numbers here are telling us, it helps to disaggregate the death tolls into the two main dimensions of war: how many there were, and how lethal each kind was. Figure 6–3 shows the raw totals of the conflicts of each kind, disregarding their death tolls, which, recall, can be as low as twenty-five. As colonial wars disappeared and interstate wars were petering out, internationalized civil wars vanished for a brief instant at the end of the Cold War, when the Soviet Union and the United States stopped supporting their client states, and then reappeared with the policing wars in Yugoslavia, Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere. But the big news was an explosion in the number of purely internal civil wars that began around 1960, peaked in the early 1990s, and then declined through 2003, followed by a slight bounce.

FIGURE 6–3.

Number of state-based armed conflicts, 1946–2009

Number of state-based armed conflicts, 1946–2009

Sources:

UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset; see Human Security Report Project, 2007, based on data from Lacina & Gleditsch, 2005, updated in 2010 by Tara Cooper.

UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset; see Human Security Report Project, 2007, based on data from Lacina & Gleditsch, 2005, updated in 2010 by Tara Cooper.

Why do the sizes of the patches look so different in the two graphs? It’s because of the power-law distribution for wars, in which a small number of wars in the tail of the L-shaped distribution are responsible for a large percentage of the deaths. More than half of the 9.4 million battle deaths in the 260 conflicts between 1946 and 2008 come from just five wars, three of them between states (Korea, Vietnam, Iran-Iraq) and two within states (China and Afghanistan). Most of the downward trend in the death toll came from reeling in that thick tail, leaving fewer of the really destructive wars.

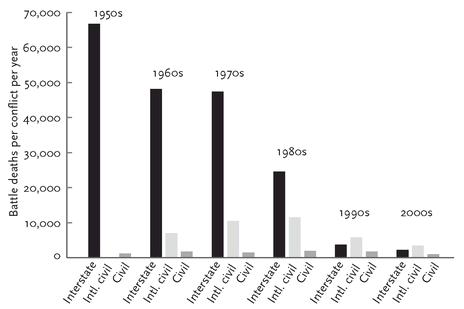

In addition to the differences in the contributions of wars of different

sizes

to the overall death tolls, there are substantial differences in the contributions of the wars of different

kinds

. Figure 6–4 shows the second dimension of war, how many people an average war kills.

sizes

to the overall death tolls, there are substantial differences in the contributions of the wars of different

kinds

. Figure 6–4 shows the second dimension of war, how many people an average war kills.

FIGURE 6–4.

Deadliness of interstate and civil wars, 1950–2005

Deadliness of interstate and civil wars, 1950–2005

Sources:

UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset, Lacina & Gleditsch, 2005; adapted by the Human Security Report Project; Human Security Centre, 2006.

UCDP/PRIO Armed Conflict Dataset, Lacina & Gleditsch, 2005; adapted by the Human Security Report Project; Human Security Centre, 2006.

Until recently the most lethal kind of war

by far

was the interstate war. There is nothing like a pair of Leviathans amassing cannon fodder, lobbing artillery shells, and pulverizing each other’s cities to rack up truly impressive body counts. A distant second and third are the wars in which a Leviathan projects its might in some other part of the world to prop up a beleaguered government or keep a grip on its colonies. Pulling up the rear are the internal civil wars, which, at least since the Chinese slaughterhouse in the late 1940s, have been far less deadly. When a gang of Kalashnikov-toting rebels harasses the government in a small country that the great powers don’t care about, the damage they do is more limited. And even these fatality rates have decreased over the past quarter-century.

26

In 1950 the average armed conflict (of any kind) killed thirty-three thousand people; in 2007 it killed less than a thousand.

27

by far

was the interstate war. There is nothing like a pair of Leviathans amassing cannon fodder, lobbing artillery shells, and pulverizing each other’s cities to rack up truly impressive body counts. A distant second and third are the wars in which a Leviathan projects its might in some other part of the world to prop up a beleaguered government or keep a grip on its colonies. Pulling up the rear are the internal civil wars, which, at least since the Chinese slaughterhouse in the late 1940s, have been far less deadly. When a gang of Kalashnikov-toting rebels harasses the government in a small country that the great powers don’t care about, the damage they do is more limited. And even these fatality rates have decreased over the past quarter-century.

26

In 1950 the average armed conflict (of any kind) killed thirty-three thousand people; in 2007 it killed less than a thousand.

27

How can we make sense of the juddering trajectory of conflict since the end of World War II, easing into the lull of the New Peace? One major change has been in the theater of armed conflict. Wars today take place mainly in poor countries, mostly in an arc that extends from Central and East Africa through the Middle East, across Southwest Asia and northern India, and down into Southeast Asia. Figure 6–5 shows ongoing conflicts in 2008 as black dots, and shades in the countries containing the “bottom billion,” the people with the lowest income. About half of the conflicts take place in the countries with the poorest sixth of the people. In the decades before 2000, conflicts were scattered in other poor parts of the world as well, such as Central America and West Africa. Neither the economic nor the geographic linkage with war is a constant of history. Recall that for half a millennium the wealthy countries of Europe were constantly at each other’s throats.

The relation between poverty and war in the world today is smooth but highly nonlinear. Among wealthy countries in the developed world, the risk of civil war is essentially zero. For countries with a per capita gross domestic product of around $1,500 a year (in 2003 U.S. dollars), the probability of a new conflict breaking out within five years rises to around 3 percent. But from there downward the risk shoots up: for countries with a per capita GDP of $750, it is 6 percent; for countries whose people earn $500, it is 8 percent; and for those that subsist on $250, it is 15 percent.

28

28

A simplistic interpretation of the correlation is that poverty causes war because poor people have to fight for survival over a meager pool of resources. Though undoubtedly some conflicts are fought over access to water or arable land, the connection is far more tangled than that.

29

For starters, the causal arrow also goes in the other direction. War causes poverty, because it’s hard to generate wealth when roads, factories, and granaries are blown up as fast as they are built and when the most skilled workers and managers are constantly being driven from their workplaces or shot. War has been called “development in reverse,” and the economist Paul Collier has estimated that a typical civil war costs the afflicted country $50 billion.

30

29

For starters, the causal arrow also goes in the other direction. War causes poverty, because it’s hard to generate wealth when roads, factories, and granaries are blown up as fast as they are built and when the most skilled workers and managers are constantly being driven from their workplaces or shot. War has been called “development in reverse,” and the economist Paul Collier has estimated that a typical civil war costs the afflicted country $50 billion.

30

FIGURE 6–5.

Geography of armed conflit, 2008

Geography of armed conflit, 2008

Countries in dark gray contain the “botttom billion” or the world’s poorest people. Dots represent sites of armed conflict in 2008.

Sources:

Data from Harvard Strand and Andreas Forø Tollefsen, Peace Research Institute of Olso (PRIO); adapted from a map by Halvard Buhang and Siri Rustad in Gleditsch, 2008.

Data from Harvard Strand and Andreas Forø Tollefsen, Peace Research Institute of Olso (PRIO); adapted from a map by Halvard Buhang and Siri Rustad in Gleditsch, 2008.

Also, neither wealth nor peace comes from having valuable stuff in the ground. Many poor and war-torn African countries are overflowing with gold, oil, diamonds, and strategic metals, while affluent and peaceable countries such as Belgium, Singapore, and Hong Kong have no natural resources to speak of. There must be a third variable, presumably the norms and skills of a civilized trading society, that causes both wealth and peace. And even if poverty does cause conflict, it may do so not because of competition over scarce resources but because the most important thing that a little wealth buys a country is an effective police force and army to keep domestic peace. The fruits of economic development flow far more to a government than to a guerrilla force, and that is one of the reasons that the economic tigers of the developing world have come to enjoy a state of relative tranquillity.

31

31

Whatever effects poverty may have, measures of it and of other “structural variables,” like the youth and maleness of a country’s demographics, change too slowly to fully explain the recent rise and fall of civil war in the developing world.

32

Their effects, though, interact with the country’s form of governance. The thickening of the civil war wedge in the 1960s had an obvious trigger: decolonization. European governments may have brutalized the natives when conquering a colony and putting down revolts, but they generally had a fairly well-functioning police, judiciary, and public-service infrastructure. And while they often had their pet ethnic groups, their main concern was controlling the colony as a whole, so they enforced law and order fairly broadly and in general did not let one group brutalize another with too much impunity. When the colonial governments departed, they took competent governance with them. A similar semianarchy burst out in parts of Central Asia and the Balkans in the 1990s, when the communist federations that had ruled them for decades suddenly unraveled. One Bosnian Croat explained why ethnic violence erupted only after the breakup of Yugoslavia: “We lived in peace and harmony because every hundred meters we had a policeman to make sure we loved each other very much.”

33

32

Their effects, though, interact with the country’s form of governance. The thickening of the civil war wedge in the 1960s had an obvious trigger: decolonization. European governments may have brutalized the natives when conquering a colony and putting down revolts, but they generally had a fairly well-functioning police, judiciary, and public-service infrastructure. And while they often had their pet ethnic groups, their main concern was controlling the colony as a whole, so they enforced law and order fairly broadly and in general did not let one group brutalize another with too much impunity. When the colonial governments departed, they took competent governance with them. A similar semianarchy burst out in parts of Central Asia and the Balkans in the 1990s, when the communist federations that had ruled them for decades suddenly unraveled. One Bosnian Croat explained why ethnic violence erupted only after the breakup of Yugoslavia: “We lived in peace and harmony because every hundred meters we had a policeman to make sure we loved each other very much.”

33

Many of the governments of the newly independent colonies were run by strongmen, kleptocrats, and the occasional psychotic. They left large parts of their countries in anarchy, inviting the predation and gang warfare we saw in Polly Wiessner’s account of the decivilizing process in New Guinea in chapter 3. They siphoned tax revenue to themselves and their clans, and their autocracies left the frozen-out groups no hope for change except by coup or insurrection. They responded erratically to minor disorders, letting them build up and then sending death squads to brutalize entire villages, which only inflamed the opposition further.

34

Perhaps an emblem for the era was Jean-Bédel Bokassa of the Central African Empire, the name he gave to the small country formerly called the Central African Republic. Bokassa had seventeen wives, personally carved up (and according to rumors, occasionally ate) his political enemies, had schoolchildren beaten to death when they protested expensive mandatory uniforms bearing his likeness, and crowned himself emperor in a ceremony (complete with a gold throne and diamond-studded crown) that cost one of the world’s poorest countries a third of its annual revenue.

34

Perhaps an emblem for the era was Jean-Bédel Bokassa of the Central African Empire, the name he gave to the small country formerly called the Central African Republic. Bokassa had seventeen wives, personally carved up (and according to rumors, occasionally ate) his political enemies, had schoolchildren beaten to death when they protested expensive mandatory uniforms bearing his likeness, and crowned himself emperor in a ceremony (complete with a gold throne and diamond-studded crown) that cost one of the world’s poorest countries a third of its annual revenue.

Other books

Play Dates by Leslie Carroll

Choked Up by Janey Mack

You'll Think of Me by Franco, Lucia

Lose the Clutter, Lose the Weight by Peter Walsh

A Death in the Lucky Holiday Hotel by Pin Ho, Wenguang Huang

Christmas Angel by Amanda McIntyre

Dragon Marked: Supernatural Prison #1 by Jaymin Eve

The Mist by Carla Neggers

In Search of Herobrine: A Famous Novel About Minecraft by De Blanc, Steve

Story's End by Marissa Burt