The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History (16 page)

Read The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History Online

Authors: Daniel Diehl

This image (taken by the authors at the Museum of Medieval Torture in Prague, Czech Republic) shows an example of the rack. The victims would be laid on their back on the ‘bed’ and their ankles would be locked into the restraints while their hands would be stretched up over their head and attached to the rope on the windlass. Spiked rollers would penetrate along the length of the spine and lower back augmenting the agony of having the wrists, elbows, shoulders, hips, knees and ankles systematically dislocated before the separation of the vertebrae of the spine. However, few victims held out long enough for it to reach that stage.

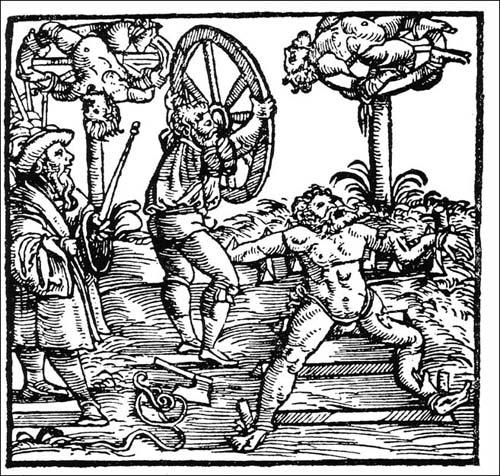

This image shows a synthesis of breaking with and braiding into the wheel. Whether the official on the left is holding a staff of office or a club to be used on the victims is uncertain. If the torturer did his job correctly, the victims would have every major bone in their bodies broken but with no fatal injuries and would then be left in their excruciating condition to slowly die of exposure.

Everywhere, victims of Henry’s paranoia were tortured, hanged and burned. Monks, priests and nuns were burnt for their faith as were protestant ministers and deacons. Noblemen went to the block or were hanged, drawn and quartered for defying the king’s orders to slaughter the common people in ever greater numbers. In one tragic case a boy of fifteen was burnt for repeating snatches of banned liturgy that it would have been nearly impossible for him to understand because they were in Latin. Over the course of Henry VIII’s thirty-eight-year reign it is estimated that 72,000 men, women and children were executed. How many more were tortured is impossible to guess.

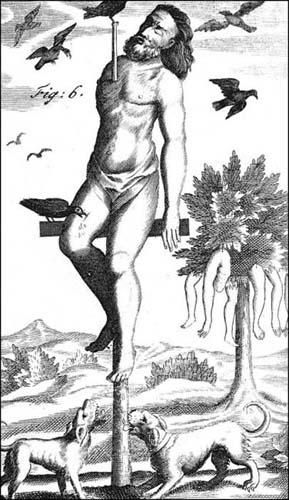

It would be heartening to say that the England of Henry VIII represented a tragic but isolated instance in the increased use of torture, but such was not the case. Throughout Europe, as religion factionalised and intolerance and fear increased, torture became more prevalent than it had been since the Roman persecution of the Christians more than 1,000 years earlier. Breaking on the wheel was becoming one of the most common means of execution in both France and Germany and for lesser crimes the French now sent men on extended sea cruises as galley slaves – a practice not employed since the Roman Empire. Half a century earlier, in the Eastern European principality of Walachia (now part of Romania), Prince Vlad III, known alternatively as Dracula (son of the dragon) or Tepes (the impaler) executed local miscreants, recalcitrant noblemen and captured enemy soldiers by impaling them on sharpened poles and using their carcasses as a warning along the border he held against the Turks.

Here we see an impaling. The spike has been passed up through the victim’s rectum and in this case has emerged out of his chest. If the spike managed to miss the heart, lungs and brain, then the victim could be alive for a considerable amount of time before finally succumbing to their wounds. Some executioners who favoured this method took great pride in their ability to achieve this.

When Henry VIII finally had the good grace to die, his throne was assumed by his son, Edward VI. In addition to ending the religious terror and firmly establishing the Church of England as a Protestant institution, Edward outlawed many of his father’s more barbaric punishments, including boiling alive. Would that this reform could have lasted. Sadly, Edward died at the age of fifteen after ruling for slightly less than six years and his place was taken by his eldest sister, Mary, whose enforced reversion of England to the Catholic faith earned her the undying sobriquet ‘Bloody Mary’.

Mary’s particular brand of faith did credit neither to herself nor the Catholic Church which she claimed to represent. Everyone who had converted to her father’s Church was ordered to re-convert to the Church of Rome or suffer penalties even her monstrous father had never dreamed of. To enforce her draconian laws she selected Edmund Bonner, Bishop of London. Known as ‘The Devil’s Dancing Bear’, Bonner was the sort of man who enjoyed taking his work home with him. In his house he installed a private torture chamber where he could discuss matters with his more reluctant victims. Even in public court, Bonner delighted in torturing witnesses and defendants alike. In one instance, a witness who did not give the answers Bonner wanted to hear had a candle flame held beneath the palm of his hand until the flesh burnt. On another occasion, a witness had his thumbs tied together and a barbed arrow pulled backward between them. The rack was in such constant usage that seldom a day went by when some poor soul was not being disjointed in the basement of the Tower of London. Single punishments were seldom enough to satisfy Bonner. When a Protestant Minister was accused of possessing ‘scandalous books [which spoke] against kings, peers and prelates’, Bonner had him severely whipped before being locked into the pillory where one ear was cut off and one side of his nose was split with a knife. He was then branded on one cheek with a red-hot iron. A week later he was returned to the pillory to be whipped until his back looked like half-digested meat, the remaining ear was hacked off, the other side of his nose split and the other cheek branded. Obviously the man had said something to offend the Devil’s Dancing Bear. In most cases, a turn at Bonner’s pillory consisted of little more than the usual public humiliation – with the exception that the victim’s ears tended to be nailed to the wooden back-board. When their stretch in the pillory was over, their ears were either ripped free or cut loose with a knife.

This image depicts a Swiss version of the pillory. The result is the same. Note how the figures on the right-hand side of the image are selecting stones to throw at the culprit. And while the image does not show his wrists bound and thereby incapable of self-defense, it appears as though the entire pillory is designed to spin which may make for additional sport for the outraged public.

Precisely how many people died for the sin of holding fast to their faith during Bloody Mary’s five years on the throne is unknown. What is known is that in London alone, between 1553 and 1558, 113 men, women and children were consigned to the flames; eighty-nine of them sent there by Bishop Edmund Bonner. For his part in this crime spree, when Mary’s sister Elizabeth assumed the throne in 1558, she sent the former bishop to the Tower where he spent the ten years until his death contemplating his sins.

When compared with the rest of her family, Elizabeth I had an amazingly enlightened outlook on how she intended to govern her kingdom. In a land exhausted by three decades of religious turmoil her first task was, obviously, to heal the festering wounds of fanaticism. In her maiden speech to Parliament, Elizabeth said: ‘There is one God and one Christ Jesus, and all the rest is a dispute over petty trifles’. Although she reverted England to the Protestant religion established by her brother, Edward, and imposed a tax on Catholics, she would not allow them to be persecuted. In an honest, and startlingly progressive, move to deal with the poverty brought on by her father’s decimation of the country and the Wars of the Roses of the previous century, she established work houses for the poor, hospitals for the ill and extended and improved the prison system. None of this is to imply that she did away with either torture or plentiful executions. Indeed, torture to collect information probably reached its height during her reign and the annual number of executions hovered around 800 per year when Elizabeth assumed the throne and climbed steadily throughout her reign. Elizabeth might well have reversed this trend despite the fact that her Privy Council, and particularly her spy master, Sir Francis Walsingham, used torture as a routine method of discovering desirable information. She might have reversed the trend, that is, had it not been for one thing: her meddlesome cousin, Mary Stuart, Queen of Scotland.

Mary, herself, was more French than Scot. Her mother was French and Mary was the widow of a French king and only returned to Scotland following her husband’s death. After the glories and grandeur of the French court, Scotland must have come as something of a shock. Hard, cold and unforgiving, Scotland bred people as tough as its climate. Brutal tortures were routine in Scotland. Thieves and forgers had their hands struck off, branding on the hands, face and body were common and whippings and scourgings were carried out for the smallest offences.

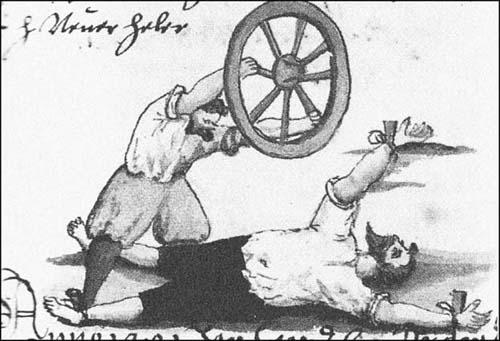

Here we witness a victim who has been staked out and is about to be broken on the wheel. Further torments undoubtedly await this unfortunate wretch.

One of the more decorative forms of execution popular in Scotland (as it was in France and Germany) was being ‘broken on the wheel’. The wheel in question was not the elaborate drum used by the Romans, but a simple cart wheel. The condemned was tied, spread eagle, to the wheel and his limbs and joints were then smashed with a mallet or an iron bar. Next, great pieces of flesh were torn from his body with red-hot pliers and only then was his head struck off with an ax. All of this, combined with the religious fanaticism of John Knox, head of the Scottish Presbyterian Church who openly referred to the new queen as a ‘bloody Catholic whore’, made Mary feel a little uncomfortable. All she wanted was a nice, relatively civilised country to rule – preferably one that was Catholic, or one that she could convert to Catholicism. England seemed an ideal choice. Escaping across the Scots/English border, Mary demanded that her cousin Elizabeth provide her with political refuge. Being no fool, Elizabeth complied, but the sanctuary came with a price – perpetual imprisonment. Both Elizabeth and her Privy Council knew that Mary, like her mother, Marie de Guise, was an inveterate plotter and England was full of ardent Catholics who would have loved to see the kingdom revert to the Church of Rome.

Elizabeth’s advisors and Spy Master, Sir Francis Walsingham, begged the Queen to have Mary executed. For seventeen years they begged her, but Elizabeth had no intention of being the first monarch in modern history to order the death of another. At least not until the late summer of 1586 when Walsingham informed his queen that he had uncovered a plot by Sir Anthony Babington, a high-born English Catholic, wherein Mary had agreed to Babington’s suggestion that he and his friends kidnap and murder Elizabeth and put Mary on the throne. There is little doubt that Walsingham had carefully amended Mary’s letter to make her seem more complicit than she actually was, but in the world of political manoeuvring it is results that count. Elizabeth went into the kind of rage that seems to characterise a Tudor monarch. In a letter to Walsingham, she wrote: ‘In such cases there is no middle course, we must lay aside clemency and adopt extreme measures. If they shall not seem to you to confess plainly their knowledge, then we warrant you cause them to be brought to the rack and first to move them with fear thereof … Then, should the sight of the instrument not induce them to confess, you shall cause them to be put to the rack and to find the taste thereof … until you shall see fit’. Mary was hustled into seclusion and Babington and fifteen co-conspirators were hauled to the Tower. Two were released because they were actually Walsingham’s spies but the remaining fourteen were found guilty of high treason and sentenced to be hanged, drawn and quartered.