The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History (15 page)

Read The Big Book of Pain: Torture & Punishment Through History Online

Authors: Daniel Diehl

Henry’s first step in redressing the shortcomings in his legal system was to limit the number of times someone could claim benefit of clergy to a single incidence; after that they would be tried in lay courts. To make certain that no one could hide their past conviction in an ecclesiastic court, Henry decreed that those being granted benefit of clergy be branded on the thumb. Upon conviction, the prisoner’s thumbs were tightly bound together with cord while a hot iron was pressed against the flesh. As the skin seared and smoked, the torture master declared to the judge: ‘A fair mark, my Lord’.

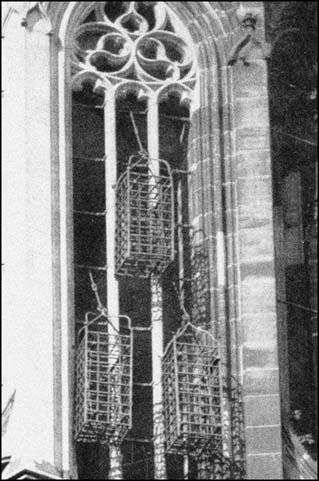

Three cages hanging ever since the early 1500s from the apse of the cathedral of Munster Germany. It was within these cages that wrongdoers would be left to die of starvation, dehydration and exposure for their perceived crimes. Their public display would have served as a warning to other members of the populace and would also serve to underline the authority, control, and power of the church and city government over the citizens of the city.

When Henry VII died in 1509 he was succeeded by his son, the much-married Henry VIII. Following in his father’s reforming footsteps, the new Henry declared that anyone accused of murder on a public highway or in church could not claim benefit of clergy, thereby making them liable to receive the death penalty. He soon extended these crimes to include all murder, piracy, rape, abduction and sacrilegious acts of all kinds. As Henry aged, his once sunny disposition soured. His protracted war with the Pope, brought about by the Vatican’s refusal to grant him a divorce, did nothing to improve his mood and he soon took out his frustrations on his subjects. Punishments of all types became ever more creatively brutal. When a sailor and his common-law wife were accused of stealing a chest of Henry’s gold from the hold of a ship, he ordered them to be wrapped in chains and suspended from the Thames embankment; when the tide came in they were slowly engulfed by the rising water. A guard at the Tower of London who was suspected of complicity in their crime was similarly bundled in chains and hung from the walls of the Tower where he was left to die of exposure.

The Roman Inquisition burning off the tongue and lips of a dissenter with a red-hot iron.

Vagabonds, hobos and the homeless always bothered Henry. People with too much time on their hands were probably trouble-makers and likely to foment rebellion. The old law prescribing a good whipping for layabouts was amended to include being burned through their right ear with a hot iron, marking them, as well as their crime, for life. A second offence brought them to the hangman’s noose. Worse crimes brought such creative sentences as having the tongue ripped out, hands chopped off and – in a move reminiscent of the worst of Roman atrocities – boiling in oil. When the Bishop of Rochester died of food poisoning in 1531, his cook was accused of the crime and boiled alive at London’s Smithfield Horse Market without even being allowed to make his last confession. This was one of two such instances that same year.

Not everyone in Henry’s government agreed with such harsh measures. Henry’s Chief Minister of State, Sir Thomas More, pleaded for less severe laws, but when he openly opposed Henry’s separation with the Catholic Church and establishment of the new Church of England, More went to the headsman’s block and his proposed reforms died with him. Henry formally established his own religion in 1534 and by 1539 made his power absolute over both Church and State with the Act of Six Articles. Crimes against the Church were now considered crimes against the king; crimes against the king were crimes against God. Henceforth, a person’s failure to attend Henry’s Church regularly brought a sentence of having their ears cut off. Anyone denying the king’s right to decree the word of God could be hanged. Anyone adhering to either traditional Roman Catholicism, or taking up the new Protestant religion would be burned as a heretic. Anyone caught eating meat on Friday, or denying the doctrine of transubstantiation (the belief that the wine and bread used in Holy Communion literally transformed themselves into the body and blood of Christ during the service) would be burned as a heretic. When a merchant named Thomas Sommers was caught in possession of the writings of the German Protestant Martin Luther he was condemned to be stoned to death. Heresy and treason were now the same crime and even being heard to utter a word against King Henry was liable to lead to the torture chamber and the burning stake.

To forestall any possible, organised opposition, Henry spent the years between 1535 and 1539 disassembling the English monastic system and tearing down monasteries. The fact that these religious houses provided the entirety of the kingdom’s charity to the poor, all of its hospitals and nearly all of its educational facilities, mattered not to the king. When an army of somewhere between 50,000 and 75,000 common people rose in revolt against the dissolution of the monasteries, Henry became convinced that the Roman Church was out to destroy him. Hundreds were sent to the burning stake, hundreds more were hanged in towns, villages and crossroads across the kingdom, but Henry remained certain that a rebellion was fomenting and the only way to get to the bottom of it was to torture the truth out of everyone who even looked like they might be a closet Catholic or a private Protestant.

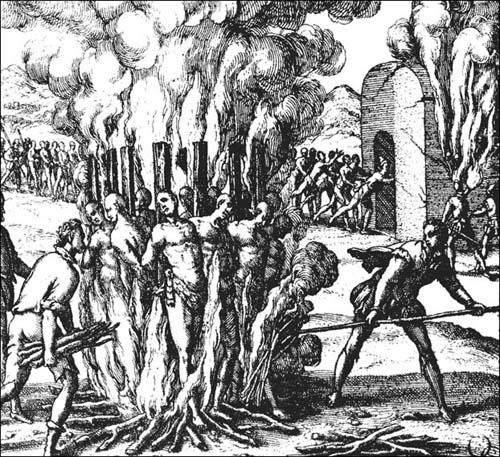

This scene from Johan Coppenburg’s

Le Miroir de la tyrannie espagnole perpetree aux Indes Occidentales

(The mirror of Spanish tyranny perpetrated against the Indians in an effort to Christianize them) shows a collection of ‘heretics’ being burned together in a great conflagration. Remember that this was believed by the executors to be a charitable act of redemption and salvation imposed upon the perceived heathens.

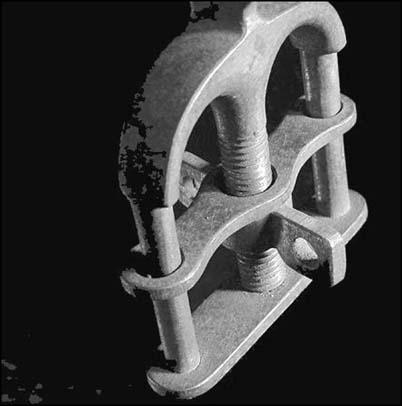

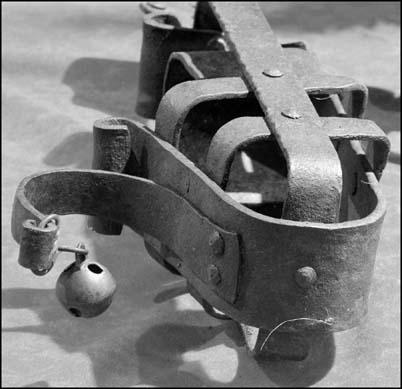

The problem with this idea, despite what you have read over the past eight or nine pages, is that torture still remained illegal in England. No matter how much pain and mutilation was inflicted on an individual, if it was a part of a punishment or death sentence it was not considered torture. Extracting information by means of applied pain, however, was. To circumvent this little glitch in the system, Henry created the Star Chamber, a court which answered to no-one and was not subject to the laws of Parliament nor to the dictates of Common Law. As a result, the thumb screws (which could crush a victim’s thumb knuckle), the boot (an iron boot that could crush the ankle bone and was sometimes applied red-hot), the scavenger’s daughter (which crushed the body until blood squirted from the nose, mouth, ears and finger tips), and the rack (which pulled a person’s limbs until the joints were dislocated) all became common methods of extracting information. Reserved for special prisoners were hell-holes in the Tower known as Little Ease (a cell so small that a man could neither lie down nor stand up but was forced to remain in a crouched position) and the Dungeon Among the Rats (a cell so filled with rodents and insects that occupants frequently had the flesh eaten from their arms and legs while they slept).

This simple but devilish device shows the functional mechanics of how thumbscrews (and later thumbcuffs) would function. Of course there were many different types and styles and designs, but they all (for the most part) functioned the same … they could be tightened more and more, increasing pressure on the thumbs until such time as the thumbs were completely severed. To get a sense of what this may have been like, we suggest that you use one hand to squeeze the knuckle of your other thumb. … Now imagine that sensation times about a billion … and only ceasing when someone else decides to release you. This sort of empathy for the victims of torture should perhaps not be attempted in every description of this book.

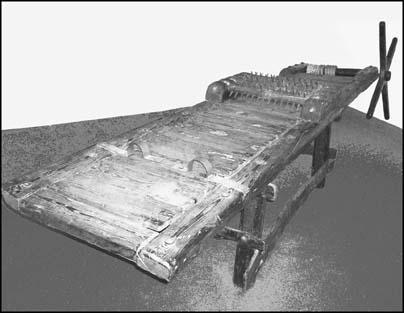

This device (aptly named ‘the boot’) would slowly crush the bones of the foot. Some devices ground the bones together laterally – others were designed for breaking each bone in turn vertically – this contraption applied increasing amounts of pressure linearly from the heel, crushing first the bones in the toes and then further application would shatter the metatarsals in the feet. Archbishop Gandier was famously subjected to the boot in order to confess his heresies to the Inquisition only to then be forced to ‘walk’ to his own execution where he would be consigned to the fires of faith. Of course walking after having endured such devastating torture was wholly impossible.