The Big Music (55 page)

Authors: Kirsty Gunn

In 1903, the Piobaireachd Society was founded with the aim of recording the corpus of existing tunes, collating the various versions and publishing an authoritative edition. Those normative tune settings have been the basis on which Ceol Mor competitors at the various Highland Games have been judged ever since, with the piping judges themselves being appointed by the Society.

In recent decades pipers and researchers have increasingly questioned the

editing

of the tunes that went in the Piobaireachd Society books, arguing that the

performance

style chosen favoured one piping tradition at the expense of others. Many compositions also appear to have been edited and distorted to make them conform unnecessarily to particular recognised tune structures. This standardisation of the transcribed piobaireachd tunes has made the judging of competitions easier at the expense of the ornate complexity and musicality of an art that had passed down from teacher to pupil through the oral transmission of repertoire and technique.

Independent documentation of this tradition of oral transmission can be found in canntaireachd manuscripts, chanted vocable transcriptions of the music that

predate

the normative musical scores authorised by the Piobaireachd Society and

enforced

through prescriptive competition judging citeria. In a belated but nevertheless constructive response to this debate over authority and authenticity, the

Piobaireachd

Society has recently made a range of these canntaireachd manuscripts available online as a comparative resource.

i

History

The bagpipe is, along with the harp and the drum, the oldest of instruments. It is not particularly Scottish, and indeed its introduction to Scotland may well have been in comparatively recent times when one sees representations of a similar-looking instrument on the papyrus scrolls of Ancient Egypt and set in stone on the engraved tablets of Mesopotamia.

It is unlikely therefore that it was ‘invented’ but, rather, more organically

developed

and changed through time. To graduate, say, from a one-note whistle to a more sophisticated many-note pipe takes not so much ingenuity as ingenuity and time – and it is highly likely that different versions of the instrument we now know as the bagpipe were coming into being at different places at different periods of history. Adding, first, to the simple pipe a bag as a reservoir for air, enabling the player to continue the melody while taking a breath, putting to that a drone, to

provide

a bass sound, adding other pipes to the solo instrument … And so on. After all, given an instrument able to produce first a note, then more notes around it, the invention of a bagpipe was perhaps inevitable. Shepherds and others who looked after grazing animals have long been associated with bagpipes, and no doubt the boredom of their task helped greatly in both the development of this instrument and the playing of it.

Whatever its origin, it is safe to assume that the bagpipe has been played from a very early time and is therefore as much a part of our sense of civilisation as gourds and goblets, temples, tablets and feasts.

It was brought to Scotland, a version of it, ‘that instrument of war of the Roman Infantry’ as Procopius described it (see Bibliography/Music: General –

Dictionary of Music and Musicians

), by those early invaders and was quickly and richly developed by the Picts and Celts as an instrument for entertainment and song – the Irish Ulleian pipe, a much lighter, ‘thinner’ version of the great Highland bagpipe, continues that tradition of play to the present day.

The development of all musical instruments was no doubt conditioned by two basic problems of how to sustain a note and how to make it loud enough to be heard by the audience. Less fundamental were the questions of scale and harmony, although once the instrument fulfilled the basic demands these became the chief problems and the main fields of improvement.

The bagpipe, then, was one solution to the difficulty of maintaining the flow of music. With no real effort of design, the loudness challenge was probably solved simultaneously.

How much the Romans, and their deployment of the instrument on occasions of battle, may have influenced its popularity we can only measure by the steady

increase

in piping culture in the centuries that followed. There is much evidence from the Middle Ages to show that by then the cult of the bagpipe was widespread, both geographically and socially. The instrument is mentioned in Spanish manuscripts of the thirteenth century and is referred to by Dante. Froissart and Boccaccio speak of it in the fourteenth century, and Chaucer says of his miller, ‘A baggepype wel coude he blowe and sowne’. In the sixteenth century, Rabelais, Ronsard, Cervantes, Spenser and Shakespeare all have references to bagpipes.

And these references sound across social barriers and classes. As well as being popular at country fairs and weddings, the instrument was to be found in the courts and palaces of kings and queens. Ladies of the French aristocracy played small versions of the bagpipe, the cornemuse. Henry VIII left five sets of pipes in his collection of musical instruments at Hampton Court. The bagpipe appears regularly in English illuminated manuscripts and ecclesiastical carvings, especially of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, but the widespread popularity of the instrument is best heard out in the fact that today, in countries as diverse as Scotland, India, Russia, Spain and elsewhere, a version of the bagpipe is being played by those who have been taught the instrument in unbroken succession since it was first introduced there. Only in the last hundred years or so have the Scandinavian countries, as well as Holland, Belgium and Germany, followed England’s example already set, for they long before gave up the playing of this unique, strange and mortal instrument that

has been always too loud, so it was deemed, to be played inside. The ceilings were too low in the music rooms of the rising bourgeoisie, their cultural appetites too sated by what they thought they wanted and needed, the windows closed and the expensive carpets of their drawing rooms near glued to their floors. There was no place for the pipes in this new sealed-off world.

So, one might say, the end of the Middle Ages signalled a new way of life that was more urban than rural – social life conducted indoors and no longer on the village green. Loudness was no longer a necessary quality, sweetness and delicacy were more highly prized. Chamber music and, in time, the modern orchestra and its pleasures were to follow the new social patternings – our definition of all the aspects of what we now call Western music were thus laid down.

This way of life was exterminated with the defeat at Culloden in 1746, of course. The Disarming Act that followed proscribed the wearing of the tartan or Highland dress, the speaking of Gaelic and the carrying of arms – which was interpreted by the law to also include a ban on the playing of bagpipes. The act was not repealed until 1782 – and yet although by then it had effectively killed a way of life, it had not quietened the sound of the pipes. The colleges of piping may have been disbanded and the number of pipers diminished, but the traditional passing on of knowledge and skill continued unimpeded. Indeed, piping now received fresh vigour in the

raising

of the Highland regiments – and it was in this way that the music made its first real impact on the rest of the world.

So it had been rejected in earlier times as an instrument of rough irrelevance, that could not be brought indoors to be played alongside the flute and the viol; nevertheless, now it had found itself a place, this lonely, uncompromising

instrument

claimed by musicians who were, at heart, never entertainers but first and foremost soloists and poets. S o now it had a meaning that sounded beyond the

complexity

of its notes and compositions. It became an emblem of a ‘self’, a Scotland that was in the process of trying to define itself as a single entity, its sound the sound of a people trying to claim for themselves a national identity, a sense of themselves that might make them feel not as though they were defeated but as though they might rise up again and always against oppression and unjust rule.

Perhaps this is why – from this time and through to the nineteenth and twentieth centuries – the pipes have been looked upon as the instrument of a barbaric country. For what coloniser wants to hear the music of its colony but only its own songs and tunes played? Certainly this may be why when contact was made between pipe music and the rest of music it was generally characterised by a measure of rejection on both sides, which tended further to increase the isolation of the pipers and to increase their sense of purpose.

The second reason for the Highland bagpipe’s survival was that at no time did its

exponents alter the instrument to make it socially acceptable. A few players,

occasionally

, may have given a non-bagpipe tune to the instrument, or modified some of the fingering, perhaps, to make a piobaireachd sound more modern, but these aberrations were few and pass in the history of the instrument largely unremarked. Once out of his natural environment the piper might accept that his music was different and strange, but this did not affect his playing of it. While other pipes softened and

lightened

, the Highland bagpipe remained. Its shape and sound and make-up, the music for which it was created, went unchanged – the same piobaireachd played in the same way with the same sound as was played by the MacCrimmons of Skye in the fifteenth century and earlier (see Appendix 14: ‘The cultural history of bagpipe playing’).

The final reason for the survival of this lonely instrument, and for its later ‘popularity’, comparatively speaking, is the character of the music with which it is inextricably linked – the Big Music, piobaireachd – a form of communication so important to Highlanders for so long that there was little chance of it being

abandoned

. As MacNeill writes: ‘If all other pipe music were to fade away there would still remain a group of Highland pipers dedicated to the study and enjoyment of Ceol Mor.’ For that, as we shall see in the next Appendix, we have to thank the legacy of that family of musicians and poets and teachers that played down from

generation

to generation: the MacCrimmons of Skye.

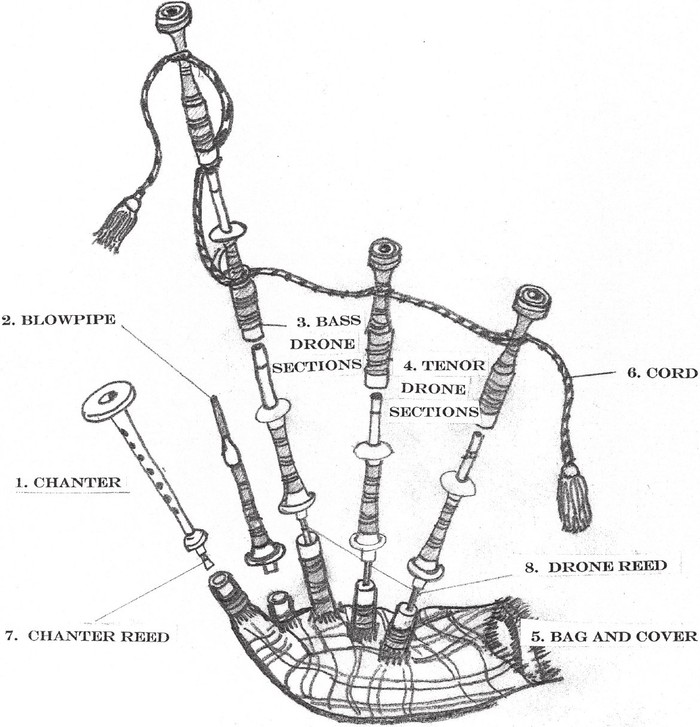

Anatomy

The parts of the bagpipe and its overall construction and shape are as complicated and intricate as its history. An ‘anatomical’ representation of the instrument may provide information as to how the various elements of the instrument come together.

Note: The pipe bag itself is the reservoir for the air that powers the reeds. This bag is usually made from leather, although modern bags are often made from

synthetic

replacement materials. The drones, which extend from the chanter, are in many ways the most important element of the bagpipe. Known as ‘the heart of the instrument’, they provide the sound with the clean, dulcet tones needed for its music. The original Highland pipes probably comprised a single drone, with the second drone being added in the mid- to late 1500s. The third, or the great drone, came into use sometime in the early 1700s.

In the Scottish Lowlands, pipers were part of the travelling minstrel class,

performing

at weddings, feasts and fairs throughout the Border country, playing song and dance music. Highland pipers, on the other hand, appear to have been more strongly influenced by their Celtic background and occupied a high and honoured position.

The skill of playing has to be blended with the art of posture and stance. The piper’s left arm should only squeeze the bag with enough pressure to feed the drones with air to sound the notes without disturbance or distortion. The bag is held

towards

the front of the piper’s body, allowing the shorter drone to rest on the shoulder.

Modern pipes, in the early twentieth century, were made of tropical hardwoods, usually black ebony and black wood from Africa or cocas wood from the Caribbean, with decorative rings or ferrules made of ivory. Sometimes silver was used for the lower ferrules. Prior to and throughout the eighteenth century, local hardwoods were used, commonly holly and laburnum, again horn and bone being added for decoration.

Pipers, particularly teachers, were adept craftsmen as creators both of music and their instruments. Many used to make their own pipes. A notable Scottish piper, John Ban MacKenzie, who died in 1864 and was thought to be the last of these makers, is said to have killed the sheep, stitched the bag, turned the drones, chanter and blowpipe on his simple foot-pedalled lathe, cut the oaten reeds, composed the tunes and played them, all with his own hands.

The parts of the bagpipe

The MacCrimmons

No one who is interested in the history of bagpipe playing and piobaireachd does not know about the great musicians of Skye who perfected the musical form of Ceol Mor and composed some of the most beautiful and important piobaireachd ever to be played, including the haunting and magisterial ‘Lament for the Children’ – regarded by pipers and music critics, both, to be as pure a representative of its form as exists in the playing of the Big Music.