The Big Screen (71 page)

Authors: David Thomson

It was Jack Germond on

The McLaughlin Report

who, when asked if Reagan had known about Iran-Contra, said, “They told him, but he forgot.” Reagan was a career forgetter, long before any suspicion of Alzheimer's. From reading radio commentaries during the war, he believed he had been present at events he never witnessed. As the journalist Tom Shales would point out, “When are they going to realize that with Ronald Reagan âseemed' and âwas' are one and the same?” In

Murder in the Air

(1940), a fifty-five-minute B picture, where he plays “Brass” Bancroft, there is a cockamamie plot McGuffin about a destructive ray (the Inertia Projector), and it stuck with him as the Strategic Defense Initiative, not just difficult to achieve but maybe ridiculous, and later called Star Wars, referring to the fantasy of the George Lucas movies.

Some memory losses were over matters of fact. When asked by a Los Angeles grand jury in 1962 whether he had participated in the 1952 Screen Actors Guild waiver that allowed MCA and Revue Productions (and only them) to be both producer and agent (bringing them great profits over seven unrivaled years), he reckoned he had been out of town filming

Cattle Queen of Montana

at the time. In fact, the dates for that were wrong, but no one on the jury was enough of a movie buff to know. (Very soon thereafter, Reagan was paid $75,000 for a cheap Western,

Law and Order

, as negotiated by Lew Wasserman, or MCA, his own agency.)

The montage would have to include the observations, sometimes from family members, that his winning public amiability sometimes dried up if you were with him aloneâbecause in those predicaments, he didn't always know or possess the script. At a school event, he introduced himself to his own son, Michael, as if they were strangers. Some believed there was not just boredom but emptiness behind the grin. Many actors know that troubling hole. Even those of us who feel increasingly that we are playing ourselves sense the abyss.

Is there a Syberberg available to make that film? I don't think soâit's hardly suited to the patriotic euphoria of a Ken Burns or the patient witness kept by Frederick Wiseman. Werner Herzog might do it, but the maker needs to be an American. Our current documentary perspective does not really permit Syberberg's “endless voice.” It is afraid to think out loud; it still believes the camera is reliable enough.

The closest we have come to that Reagan movie is the unexpected book

Dutch

, by Edmund Morris, published in 1999. Morris was an esteemed academic biographer at work on a multivolume life of Theodore Roosevelt (it had won him a Pulitzer Prize already) when he was diverted by an invitation to do an authorized biography on Reagan. So he watched the man and talked to him, and did all that professional biographers are meant to do. But the book didn't quite come to life, because Morris believed there wasn't an entire person there. So he was brave enough to get into scenario, or “Ronald Reagan's own way of looking at his life.” There are sections of

Dutch

written as fiction, or in an imagined attempt to match the manner with which Reagan perceived, and liked, himself. There is this passage, where Morris talks to Reagan about good and evil:

“So you do believe in the power of human goodness.”

“Of course!” he said, contact lenses twinkling. “That's what it's all about.”

The twinkle slid off as he turned to speak to Kathy [his secretary], and with it slid my reflection from his eyes, and all consciousness of me from his brain.

Morris couldn't know that, but he felt he had to say it in an authorized biography.

Dutch

was mocked and deplored, and it's hard to claim it works “properly.” But its inside approach, the resort to scenario, was intuitively stimulating. For Reagan was always hoping to be a cut-and-print acted character, and that meant we had to slip aside, too, from citizenry to audience. We may never get back.

Dread and Desire

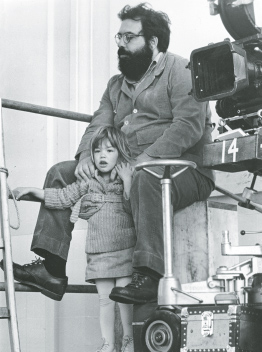

Francis Ford Coppola and his daughter, Sofia, on the set of

The Godfather: Part II

In 1947 a prescient poetic imagination had seen a streetcar passing by in an American city. It was named Desire, after one of the routes in New Orleans, and Tennessee Williams came to it after he had tried other titles. “Desire” was a mark of voodoo, perhaps, or of subterranean and surreal needs ready to battle the external grid system of a New Orleans unaware how nature and a spirited female force, Katrina, would soon carry it back in time, and not alert to the way sixty years was only a blink or a flicker in the film strip.

But in

A Streetcar Named Desire

, the Tennessee Williams play, the vehicle of desire, Blanche DuBois, is seen to be crazed so that finally she is taken off to an asylum. Stanley Kowalski knows she is dangerous, disorderly, and a bad example. He is a new man, a Polack American home from the war, his mean head filled with barrack-room law, his rights, and a crass materialism that likes to smash minor property to show his authority. So he picks up the chinaware in his own home and clears the table. And in his iconic and tight jeans and what was perceived as his audacious physicality you could feel his manhood. So he gets the disturbing sister-in-law out of his house, and he rapes desireâthat is his way of killing it.

The film of

Streetcar

that followed in 1951 hoped to be the stage production transferred. The only cast change had Jessica Tandy replaced by Vivien Leigh. But the movie had many censorship problems over its suggestion of sexual violence. At one time a “happy ending” was proposed, and Lillian Hellman delivered a script for it. By the early 1950s, the Hollywood Production Code was still in force, so that words, actions, and hints allowed onstage could not be filmed.

But the pressure was mounting. The careers of Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor, Grace Kelly, Brigitte Bardot, Sophia Loren, Jeanne Moreau, and many others cannot be followed without some realization of clothes, restraint, and shyness falling away. In

Some Like It Hot

(1959), Marilyn seems to be falling out of her dress when she sings “I'm Through with Love.” In

To Catch a Thief

(1955), on their picnic, when Kelly asks Cary Grant whether he'll have a leg or a breast, she isn't just talking cold chicken. He responds, “You decide” (a very Grantian hesitation), but is that a tribute to feminist decision making or the male's sultanate view of the movie harem?

Sometimes, in a spirit of optimism, the new woman was hailed as a step toward “feminist” advance. Soon enough, Faye Dunaway's Bonnie would be helping the diffident Clyde to his orgasm, Audrey Hepburn's Holly Golightly would be interpreted as a free spirit instead of a shopping escapist, and in

Klute,

the aggressive loneliness of Jane Fonda and her taut body were read as unstable independence instead of a concession to the Godardian idea that prostitution and being an actress were a dark sisterhood.

The breakdown of censorship in the 1960s could be interpreted as liberation. But as with many radical shifts in that era, the real impact was complicated. Female nudity and female sexual readiness were much more evident on our screens, and some said this was good for women. Yet all knew it was what men would pay for, and at the executive and creative levels, men still determined what got made and shown. So in Peter Bogdanovich's

The Last Picture Show

(1971), Cybill Shepherd showed us her breasts (and prompted the director to abandon his wife, Polly Platt, for her), but the actors' penises stayed out of sight.

As female bodies became more visible, their glamour declined. But the private parts of men became more illustrious and fetishized. In turn, this began to bring to public attention the possibility that men were erotic icons, too, and that movies might be bisexual, or multisexual, or gay.

The industry said there were some movies aimed at men (Westerns, gangster flicks, war) and some more suited to women (romances, tearjerkers, mother movies). But they were as reluctant to give up any portion of the audience as they were to acknowledge the quantity of homosexuals working in filmâand watching them. With Astaire and Rogers, their films could not be enjoyed without a male viewer saying to himself, “It sure would be swell to have Ginger in my arms, but it would be great to be able to move herâthey call it dancingâthe way Fred does. And he is so elegant, so cool, so nice, so gentle, so silly, soâ¦gay?” Equally, the woman in the audience can say to herself that it would be terrific to have a partner as athletic and considerate as Fredâbut “Don't I wish I looked like Ginger, or had her dress?” The old adage was that she gave him sex appeal, and he lent her class. But we got both.

The normal history of film is of an art, a business, and the famous people who contributed to it and who made modern celebrity. But if commercials are small movies, and if pornography has a place in the list of films made, then there must be larger issues of understanding in play. So film introduced us to a mass medium, leading us away from inner truth to appearance, confusing us over reality and fantasy, and helping us go from a state of sexual innocence or ignorance to claiming sexuality as a right. Suppose the vital history of the medium has been in making novices and strangers accustomed to sex and to seeing the chance of pleasure or desire's fulfillment. Suppose that meant being drawn to both sexes.

In Ford Madox Ford's novel

The Good Soldier

(published in 1915, the year of

The Birth of a Nation

, and far beyond Griffith's film in its human understanding), there are several characters of whom the narrator can say quite reasonably that they did not know how babies were made. These are not uneducated figures. They are wealthy pillars of society. Most of them seek sexual gratification and seem to know where to get it. But they do not apprehend the role of sex in either their own experience or the development of the culture. At that social level, few innocents like that exist any longer. In a hundred years sex has developed as an experience and a theory. It is where we grow up? And in positing the curious gap between the inner and outer aspects of sex, what it feels like and what it looks like, movie may have had a value beyond that of individual films. Thus, stardom is less about the people on-screen than those watching them. It involves the discovery of desire.

In Montgomery Clift's breakthrough film, Howard Hawks's Western

Red River

(1948), he played the adopted son who opposed John Wayne's tyrannical rancher, and took his herd of cattle from him, incurring lethal vengeance. Clift was handsome; he was beautiful. Not everyone thought he could be convincing as a robust Western heroâincluding Wayne. Did the insiders know he was bisexual? That's less clear than Hawks's belief that Clift was exciting box office and a worthy opponent for Wayneâeven in the concluding fistfight. Still, Clift had to be taught how to work with guns on his hips, a hat on his head, and a horse between his thighs. How well he managed can be seen on the screen. He was a good enough actor to impress Wayne and Hawks, and to hold the camera.

And yetâ¦Clift's character wears fringed buckskin (a costume you might purchase in a gay store now). He has private movie talk with Cherry Valance (John Ireland) about their guns, the innuendo of which was noticeable at the time. Then, at the close of the pictureâwhere the script had originally called for a deathâthe girl (Joanne Dru), who has been propositioned by both men along the trail, tells them to stop fighting and grow up, because anyone can see they love each other.

To the movie public for just a few years, Clift was an ideal romantic hero, someone Hawks had made seem valiant and effective in

Red River

. The same pattern held in other Clift pictures.

A Place in the Sun

is a blighted love story and a social allegory in which Clift meets an ordinary girl and has sex with her. The girl, Shelley Winters, is as deglamourized as wardrobe and makeup could permit. But then Clift sees and meets a girl from the screen. He has already seen an image that represents her, on a highway billboard, as he hitches a ride. She is the eighteen-year-old Elizabeth Taylor, staggeringly attractive and with a childlike tenderness. So Clift thinks to dump the pregnant Shelley and a humdrum life for the limitless horizon with a radiant Liz and “a place in the sun.” This “place” seems perfect but only as an infant's haven.

Although Clift only contemplates murder, a providential accident intervenes. Winters drowns, and because Clift knows he is guilty in his heart, he goes to his death. This guilt in the soul rhymes tidily with the lust in the heart that affected nearly everyone at the movies in those days. The tragedy in George Stevens's expert film seems fixed on Clift and Taylor and the innovative telephoto close-ups that enshrined their last embraces. But there's more, if you are prepared to see how the American dream of rising above your station and claiming your place in the shining light of happiness may be dangerous. In short, be careful with the huge fantasy urging of the movies. (As the film arrived, and made its impact, the Sands Casino opened in Las Vegas, with the engraved motto over the doorway, “A Place in the Sun.”)

In 1972,

Last Tango in Paris

had been hailed as a new world, or an available apartment where anything could happen. There were other flutters of orgy: Nicolas Roeg's

Don't Look Now

(1973) had an unusual and delicate scene in which Julie Christie and Donald Sutherland made uninhibited love and were intercut with glimpses of them dressing afterward. It was only an aside and a joke at the expense of the normal undressing scenes. It was there to say, “We can do this now,” in a picture the title of which reminded us about seeing things.

In American film, sex receded as soon as the chance of showing it had been wonâwith a few honorable exceptions. The new powers, Spielberg and Lucas, never seemed interested in love on the screen. Film was their sex. Brian De Palma was fixed on voyeurism (

Dressed to Kill

, 1980;

Body Double

, 1984) but aware of little else. Philip Kaufman made an authentically sexy film,

The Unbearable Lightness of Being

(1988, from Milan Kundera), under cover of a European art house film. In Japan and then all over the world, Nagisa Ãshima's

In the Realm of the Senses

(1976) explored the sadomasochism in passion. Marco Bellocchio's

Devil in the Flesh

(1986) had what was said to be the first filmed, or depicted, blow jobâso at last the common practice of executive offices saw the artistic light of the dark.

It wasn't truly a first for fellatio. In June 1972 a sixty-one-minute American film had opened in “pornographic” or “adult” venues. It was called

Deep Throat

and concerned a young woman who discovered that her clitoris was in her throat. The actress was credited as Linda Lovelace, though her real name was Linda Boreman. The picture was marketed with the poster catchphrase “How Far Does a Girl Have to Go to Untangle Her Tingle?” Perhaps that encouraged a sense of feminist self-discovery, and this was a moment in history when many educated, middle-class women were discovering that they might have an orgasm.

Film historians were not surprised when uglier truths emerged. The picture had cost $50,000 at the outside, and Boreman had been paid just $1,250, money that went to a husband who compelled her to make the film and may have abused her in the process. The auteur, writer-director Gerard Damiano, was supposed to have a third of any profits, but he was forced out of the enterprise with a mere $25,000. How much did the film earn? No one knows, but $100 million seems reasonable, granted that the film was banned in many places and its release was controlled by organized crime figures who may have learned how to fudge attendance income from the film business.

Still, no earlier “dirty” movie had sold so many tickets to respectable people. Even the

New York Times

admitted the film existed, though the newspaper kept its title to

Throat

. The world was shifting again. While it's fair to say that apostles of desire were often let down by the screen's long-anticipated orgyâa lot of us are inclined to fall asleep after an orgasmâthe creative pursuit of sexuality was confounded by the onset of pornography and its dwelling on routine climaxes without any moral narrative.

Some predicted that pornography would never reach through our entire culture. But the technology never knows defeat: it is our cockroach. Porno movie theaters were condemned, harrassed, and closed for years. When Travis (Robert De Niro) takes Betsy (Cybill Shepherd) to a porn flick in Martin Scorsese's

Taxi Driver

(1976), it is a fatal block to their relationship and a sign of his mental disturbance. But when Erika Kohut (Isabelle Huppert) goes on her own to a pornographic movie in Michael Haneke's magnificent

The Piano Teacher

(2001), and watches the image of a woman lying on her back taking an engorged blue-black cock (there is no better word) in her mouth, it would seem that her loneliness or pathology needs that relief if she is to carry on being such a great teacher of Schubert and living with her awful mother. The rift in her being is more convincing than the guilt or regret that Michael Fassbender is carrying in

Shame

(2011). Reports tell us that 70 percent of women in the West have watched pornographic films at some length, while the business generates around $13 billion a year, which is about $3 billion more than theatrical movies now take in America. But porn

is

movies, just like surveillance footage, and movies have always dealt in sexual excitement.