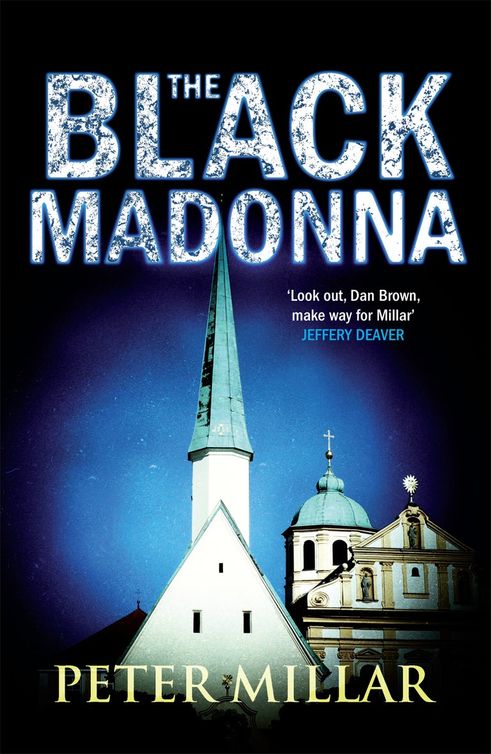

The Black Madonna

Authors: Peter Millar

Tags: #Fiction, #Action & Adventure, #Thrillers, #Suspense, #Christian

PETER MILLAR

Title Page

Foreword

Prologue

Part One: AVE MARIA, GRATIA PLENA … Hail Mary, full of Grace …

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

Part Two: … MATER DEI, ORA PRO NOBIS … … Mother of God, pray for us …

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

Part Three: … ORA PRO NOBIS PECCATORIBUS … … Pray for us sinners …

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

Part Four: … NUNC, ET IN HORA MORTIS! … Now, and at the hour of our death!

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

Epilogue

Author’s Note

About the Author

Copyright

This is a novel, a work of fiction involving adventure and intrigue. However, all the historical events, people and places referred to are accurate and verifiable. The juxtapositions are my own, and the

conclusions

are those of my characters. I invite readers to draw their own.

Peter Millar,

Munich and London 2010

‘Ich habe das Glück, ganz in der Nähe von Altötting geboren zu sein… Der stärkste Eindruck war natürlich die Gnadenkapelle, Ihr geheimnisvolles Dunkel, die kostbar gekleidete schwarze Madonna, umgeben von Weihegeschenken.’

Papst Benedikt XVI

‘I was lucky to have been born near Altötting… The greatest influence on me was the Chapel of Grace with its darkness full of secrets and the black Madonna robed in her costly finery, surrounded by offerings.’

Pope Benedict XVI

Ganz voll Vertrauen kommen wir in der Gefahren Mitte, zu Dir, Maria, rufen wir zu Dir, Maria, bewahre unsre Schritte O Mutter Gottes, wir sind dein, laß uns nicht unterliegen, wenn wir am letzten Ende sin, verlassen sind und ganz allein, O Mutter Gottes, wir sind dein

Altöttinger Wahlfahrtslied

In the midst of danger we come to you, Mary, full of trust we call out to you, Mary, guide our steps.

Oh Mother of God abandon us not, for we belong to you,

Alone at the end when all others have left us,

We belong to you.

Altötting Pilgrims’ Hymn

Ave Maria, gratia plena, Mater Dei, ora pro nobis,

Ora pro nobis peccatoribus nunc et in hora mortis

Hail Mary, full of Grace, Mother of God, pray for us,

Pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death

Mesopotamia AD363

The ancient Greeks called it the âland between two rivers', now it was hell on earth. In the baking heat of the summer sun, the soldiers in the first rank peered with scorched, reddened eyes into the hazy distance searching for their unseen assailants. None of them knew when the next attack would come, nor how many it would kill.

They had been told the natives would be grateful for their

deliverance

. The soldiers of the superpower had come to free them from despotism, to bring the Western values of law, order and civilisation to a land run by a cruel tyrant. They had advanced quickly, almost easily, pushing the enemy back across the desert to the capital, the great sprawling city on the banks of the Tigris, so unlike anything back home.

But the dream of subduing a region that plagued their leader's vision of a new world order now looked like his greatest mistake, a military blunder that could end his dream of a glorious place in history. These were not men used to retreating but now they were getting out, and getting out in a hurry; tens of thousands of them trailed in a line that was not as military in formation as their officers might have liked, across barren, hostile country.

It was a sentry on the right flank at the rear of the column who noticed the telltale signs first: shifting shapes among the rocks,

indication

that the cowardly enemy hiding unseen in the desert was closing in, preparing to strike. Most frequently the attack, when it came, hit the rearguard, like a viper sinking its fangs into a sandaled heel.

Then the wind rose, and they came out of it in a cloud of dust and deafening noise. Where there had been silence and shimmering heat haze there was suddenly a whirlwind of death and devastation, as from nowhere the ungrateful enemy opened fire on the unloved invader. Men in the marching ranks were cut down before they even knew they were under attack.

The officers tried to rally their troops but as the casualties mounted a sense of panic spread. Then in an act of supreme courage the general himself, knowing the effect his presence would have on his forces, appeared among them â bravely bare-headed so as to be immediately recognisable â urging them not to yield to mindless panic. They were, he yelled, knowing deep down they believed it themselves, the best trained army on earth, the crack troops of a global superpower, and were not about to be frightened by a bunch of cowardly curs who were little more than hit-and-run terrorists and lacked the nerve to fight them head-on.

The effect was immediate. The officers marshalled their men and what had been a rout became an advance. An enemy that preferred sniping from a distance now turned rather than engage these

professional

battle-hardened troops at close quarters. In the ranks a few men exchanged grim smiles: they would teach this desert scum another lesson, one that this time they would not forget so quickly. If their commander could face up to the enemy unprotected then they could go after that enemy and hunt them down like the desert dogs they were.

âAdvance!' came the order. There would be no stopping them now.

As at last the merciless sun began to set over the barren horizon the sands were littered with bloody corpses. Only with the fall of night, however, did the last of the enemy disperse disappearing back into their own unremittingly hostile landscape. It had been a victory, of sorts, for the good guys, or so the weary soldiers told themselves as the lucky ones settled down for the night while the less fortunate drew lots for sentry duty.

Only then did most of them hear the bad news, the news the veterans had been dreading but which even to them seemed

unbelievable

now that it had happened. The general had been hit, badly. Fearless to the last he had refused to withdraw to relative safety and been wounded in the chest. Mortally, it was feared. Within the hour the dire news was announced. The missile that had pierced his ribcage had done irreparable harm. The general was dead.

Throughout the makeshift camp the news spread like wildfire. A catastrophe had befallen them. An army in a hostile land had lost its commanding general. But the consequences would be far greater, they knew, than their own immediate plight.

The general was more than just any general â the men who had

followed him halfway around the world, from the banks of the Rhine to the shores of the Tigris, had long ago acclaimed him as more than that â he was

imperator

, the emperor. The entire Western world had lost its leader.

Late into the night, as the sentries stared into the alien darkness, groups of men sat around fire and muttered darkly to themselves as they heard the news. And one, sitting sombrely amidst a group that had lost their weapons in the battle, fell quietly to his knees and made the sign of the cross.

As all Christians knew, the death of one man could change the history of the world for ever after.

Gaza City, present day

The dust hung in the air like a dirty gauze veil across the face of the city, drawn not out of modesty but to hide its ugliness. No matter how much Nazreem Hashrawi loved her work, and of late she had come to love it very much indeed, the business of getting there was never a joy.

She picked her way through the honking horns and concrete rubble of a city that was both Mediterranean and Middle Eastern, part ancient metropolis and part jerry-built refugee camp,

negotiated

the street vendors with their piles of oranges, lemons, tomatoes and cheap cotton T-shirts, made in China. A residual tang of sea salt, rotting citrus and powdered concrete lingered in the hot heavy air. The streets were always like this nowadays. There was scarcely a building that did not seem to be in the process of construction or demolition. Bombsites and building sites resembled each other.

On the corner of Omar El-Mokhtar Street a clattering khaki truck laden with scaffolding, breeze blocks and leather-faced labourers with Arafat-style keffiyehs and stony eyes nearly sent her

sprawling

into the gutter, and prompted a shrill blast on the whistle and a sharp rebuke from a hassled-looking traffic policeman. The driver and the workers ignored him, clattering on their way. The people laughed at their own police, the bitter laughter of those who could not take their puppet state seriously, yet knew it was all they had. And perhaps all they were likely to get.

For over 2,000 years Gaza had been one of the most important cities on the Mediterranean, while from the landwards side it was the key to Egypt, a city prized by the Pharaohs before it was

captured

by the Philistines, ancestors of her own people. The Hebrews’ legends said their hero Samson had broken down its gates, but ended up blind in its jails when his hair was cut and his magical strength failed.

Alexander had laid siege for three months to wrest it from the Persian empire. In Greek and Roman times it was famed as the end of the incense road, from where ships set sail for Athens and Rome. Napoleon had called it the Forward Garrison of Africa and the Gate to Asia.

Yet for all that history, there was precious little to see. The

twentieth

century had not been kind to Gaza. Her own little museum was a token: a monument to the past in a millennia-old city that was not only unexcavated but where each day new rubble was piled upon old. It had remarkably little to boast, and much of that was

borrowed

. Or had been until now.

The events of the past week had changed everything. Which was why Nazreem was heading in to work now, on a Friday evening of all times, when the museum was closed. That meant it would be quiet, as quiet as anywhere ever was in overcrowded Gaza, and she would be undisturbed. She had a dossier to prepare, a dossier that could change her entire career and she intended to work through the night if need be.

As she took her keys from her purse and opened the side door into the museum she could hear the last call to evening prayer echoing from the minaret of the Al-Omari mosque, which had once been a crusader church, itself built on the site of an ancient pagan temple. What goes around, comes around, she smiled to herself as she climbed the stairs to the little room that served as a staff kitchen. She was going to need a pot of strong coffee.

Outside, the small dusty square was settling into its familiar sundown routine – the men gathering to smoke and argue over sweet mint tea at the dilapidated corner café, the women retiring indoors to get on with the cooking, the daytime stench of diesel exhaust gradually yielding to odours of grilling lamb and strong tobacco. Then the universe imploded.

She heard the scream first. The unmistakable high-pitched keening of a kerosene-fuelled missile. Then she felt the shock, the earth tremor of impact, a millisecond before the thunderous

detonation

, the roar of collapsing masonry. And then the human screaming started. A thick plume of dirty, grey-black smoke rose from a side street barely a hundred metres away. In the distance sirens howled against the familiar futile staccato of men firing automatic weapons into the empty sky. And in the midst of it, the building around her erupted, as if in sympathy, into a wail of its own.

Nazreem leapt to her feet in horror. For a second she had stared in shock at the unfolding drama, terrible but almost too familiar to be frightening. Now she was genuinely scared. But not for herself. She pulled open the office door and sprinted the few metres of

corridor

that led to the stairs. She knew what had happened: the alarms had gone off. The museum was being broken into.

Or rather she fervently hoped it wasn’t: that the shock wave

generated

by the nearby explosion and collapse of a building had set off the sensors. It was a coincidence, that was all. A coincidence rather than a genuine attempt to break into her museum on the first night in its still brief history that it held a find of significant importance. A find of such potential that they had tried to keep it secret, at least until it could be verified. But rumours spread. And you never knew.

You never knew what was round the next corner, she told herself as she ran into the main gallery. A pulsing red glow from the

activated

motion detectors played surreally on decapitated heads and fragments of torsos, salvaged stones from Greek and Roman

statuary.

Her city was as old as civilisation, but had next to nothing to show for it. Until now.

Then she stiffened. A shadow, or a movement in the shadows. In the flickering crimson light it was impossible to tell. The howl from the alarms was deafening, but so was the clamour outside. The police should have been here by now. The police had other things to do; there would be Hamas fighters in the street baying for Israeli blood. The shadow moved again. This time she was sure of it.

Beyond the sarcophagus. The museum’s sole relic of Egyptian mummification – on loan from Cairo – was a marble slab with a few faded hieroglyphs that proclaimed it the last resting place of an official who may or may not once have been the province’s

governor.

She was almost certain she had seen something move beyond it; between her and the object she wanted more than anything else to protect. She looked about her for a weapon, rejected a priceless ancient Pharaonic flail and settled on a small handheld fire

extinguisher.

Her sole hope was that whoever had forced entry had no idea there was anyone else in the building. She advanced cautiously, her footsteps masked by the sirens. The gallery beyond was the special exhibition space.

The sarcophagus was just a few feet away. To her left, standing upright against the wall, was the cedar mummy case it had once

contained. She shot it a passing glance and saw the shadow emerge from it. Her own scream was lost in the collective cacophony. A man’s hand clamped over her mouth and nose.

The fire extinguisher clattered from her hand, discharging its spume of chemical foam uselessly across the floor. She tried to bite fingers that were smooth but brutal, smelled of stale cigarette smoke and threatened to squeeze the life out of her, while the other hand twisted her long dark hair up into a thick knot. She cursed herself for not wearing her headscarf.

Stumbling forward, gasping for air, she could feel her captor’s breath, hot, warm and sickly sweet on the back of her naked neck. Her arms flailed helplessly against the powerful body pressed against her, earning only a painful blow from a knee to the base of her spine. She felt herself fall forward and sent sprawling onto the

chemical-covered

floor. She tried to scramble to her feet, her knees even, but her sandals floundered in the slippery white goo spreading across the parquet.

Instinctively she turned her head to try to see her assailant, pushing herself up into a crawl. She saw no more than a glimpse of a tall dark shape before a ferocious kick to the backside sent her sprawling again in agony. Frantic now, she willed her fingers to drag her away. And then he fell on her. A great crushing weight, pinning her to the floor. There was a rip, a sound of cloth tearing, cloth from her own long cotton skirt. The hand that had wound itself back into her hair jerked her head roughly from the floor and a folded strip of cloth covered her eyes, pulled so tightly it hurt her eyeballs, and she felt the knot being tied in with her hair behind her head.

Then, all of a sudden, he was off her. For a moment she almost lost control of herself completely. Was that it? Or was she

milliseconds

away from the bullet in the back of the head. She was not afraid of death; she had faced death before. But not now, not like this. She shuffled forwards on her knees. A metre, maybe two, maybe more. She would be in the exhibition room by now. Beyond that, no more than half a dozen metres away, was the door to her own office. If she reached that, then maybe … no, it was impossible.

A blow to the small of the back knocked her flat and he was on her again. Not lying this, time, but squatting on her legs. Another rip, and her arms were jerked behind her back, the wrists bound, painfully tight. Another rip and this time she felt her bare thighs

exposed, and then she felt what they were exposed to, and realised why he had released her for a second; to open his flies.

Her teeth gritted, her eyes weeping painful tears into the fabric of her own torn clothing. Still uncertain if it would end with a bullet in the head. She felt the same smooth brutal fingers rip away her underwear and force themselves into her. He was on top of her now, the free hand feeling for her breasts, the hot, sweaty weight of his belly on her buttocks and the hard penis pushing, thrusting, penetrating. Penetrating. And then she realised what was

happening.

Rape was not bad enough. The bastard was sodomising her. Nazreem Hashrawi did the one thing left to her: she screamed with all her might into the unlistening noise-filled night.

And as she did, the blindfold on her eyes slackened almost

imperceptibly

, just enough for her to glimpse, on the pedestal in the centre of the exhibition room, an ancient serene expression of endless compassion. Christians called her

Mater Misericordiae

, Mother of Mercy, the Immaculate Virgin. Nazreem’s scream became a howl of bitter rage.