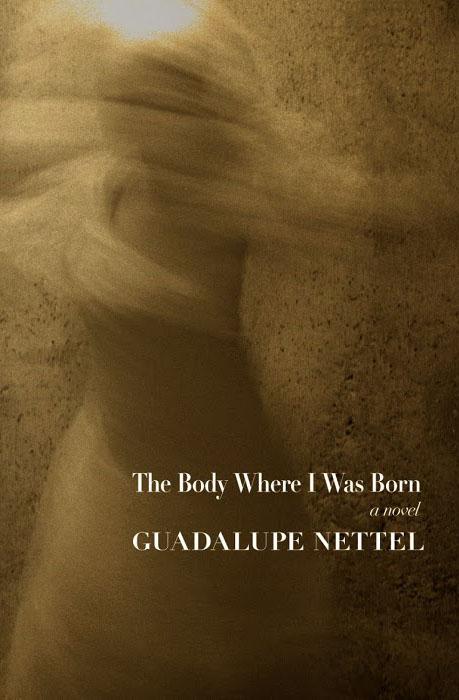

The Body Where I Was Born

Read The Body Where I Was Born Online

Authors: Guadalupe Nettel

Tags: #Fiction, #Novel, #mexican fiction, #World Literature, #Literary, #Memoir, #Biography, #Personal Memoir, #Biographical Fiction, #childhood, #Adolescence, #growing up, #growth, #Family, #Relationships, #life

The Body Where I Was Born

The Body Where I Was Born

a novel

Guadalupe Nettel

translated from the Spanish by J. T. Lichtenstein

Seven Stories Press

new york

•

oakland

Copyright ©

2015

by Guadalupe Nettel

English translation copyright ©

2015

by J. T. Lichtenstein

First English-language edition.

Title of the original Spanish edition:

El cuerpo en que nací

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Seven Stories Press

140

Watts Street

New York, NY

1

0013

www.sevenstories.com

College professors may order examination copies of Seven Stories Press titles for free. To order, visit http://www.sevenstories.com/textbook or send a fax on school letterhead to (

212

)

226

-

1411

.

Book design by Elizabeth DeLong

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Nettel, Guadalupe, 1973-

[Cuerpo en que nací. English]

The body where I was born / Guadalupe Nettel ; translated by J.T. Lichtenstein. -- A Seven Stories Press first edition.

pages cm

“First English-language edition” -- Verso title page.

Originally published as El cuerpo en que nací. Barcelona : Editorial Anagrama, 2011.

ISBN 978-1-60980-526-5 (hardback)

1. Domestic fiction. 2. Psychological fiction. I. Lichtenstein, J. T., 1986- translator. II. Title.

PQ7298.424.E76C8415 2015

863’.7--dc23

2015006198

Printed in the United States

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

For Lorenzo and Mateo

yes, yes,

that’s what

I wanted,

I always wanted,

I always wanted,

to return

to the body

where I was born.

allen ginsberg

, “Song”

I.

I was born with a white beauty mark, or what others call a birthmark, covering the cornea of my right eye. That spot would have been nothing had it not stretched across my iris and over the pupil through which light must pass to reach the back of the brain. They didn’t perform cornea transplants on newborns in those days; the spot was doomed to remain for several years. And in the same way an unventilated tunnel slowly fills with mold, the pupillary blockage led to the growth of a cataract. The only advice the doctors could give my parents was to wait: by the time their daughter finished growing, medicine would surely have advanced enough to offer the solution they now lacked. In the meantime, they advised subjecting me to a series of annoying exercises to develop, as much as possible, the defective eye. This was done with ocular movements similar to those Aldous Huxley suggests in

The Art of Seeing

, but also—and this I remember most—with a patch that covered my left eye for half the day. It was a piece of flesh-colored cloth with sticky, adhesive edges, covering

my upper eyelid down to the top of my cheekbone. At first glance, it looked like I had no eye, only a smooth surface there. Wearing the patch felt unfair and oppressive. It was hard to let them put it on me every morning and to accept that no hiding place and no amount of crying could save me from that torture. I don’t think there was a single day I didn’t resist. It would have been so easy to wait until they left me at the school entrance to yank the patch off with the same careless gesture I used to tear scabs off my knee. But for some reason I still can’t understand, I never tried to remove it.

With the patch, I had to go to school, identify my teacher and the shapes of my school supplies, come home, eat, and play for part of the afternoon. At around five o’clock, someone would come to say it was time to take it off, and with these words I would return to the world of clarity and precise shapes. The people and things around me suddenly changed. I could see far into the distance and would become mesmerized by the treetops and infinite leaves that composed them, the contours of the clouds in the sky, the tint of the flowers, the intricate pattern of my fingertips. My life was divided between two worlds: that of morning, built mostly out of sounds and smells, but also of hazy colors; and that of evening, always freeing, yet at the same time, overwhelmingly precise.

Given the circumstances, school was a place even more inhospitable than those institutions often are. I couldn’t see much, but it was enough to know how to get around within the labyrinth of hallways, fences, gardens. I liked climbing the trees. My hyperdeveloped tactile sense allowed me to easily distinguish the firm branches from the frail, and to know which cracks in the trunk made the best footholds. The real problem wasn’t so much the place as it was the other children. We knew there were many differences between us; they stayed away from me, and I from them. My classmates would ask, suspiciously, what the patch was hiding—it had to be something terrifying if it needed to be covered—and when I wasn’t paying attention, they would reach with their grubby little hands, trying to touch it. Alone, my right eye made them curious and uncomfortable. Sometimes now, at the ophthalmologist’s office or at a bench in the park, I cross paths with a patched child and recognize in them the anxiety so characteristic of my childhood. It keeps them from being still. I know it’s how they face danger—it’s evidence of good survival instincts. They’re on edge because they can’t stand the idea that a cloudy world should slip through their fingers. They have to explore, find a way to own it. There were no other children at my school like me, but I did have classmates with other kinds of abnormalities. I remember a dwarf, a redheaded girl with a cleft lip, a boy with leukemia who left us before elementary school was over, and a very sweet girl who was a paralytic. Together we shared the certainty that we were not the same as the others and that we knew this life better than the horde of innocents who in their brief existence had yet to face any kind of misfortune.

My parents and I visited ophthalmologists in New York, Los Angeles, and Boston, and also in Barcelona and Bogota, where the famous Barraquer brothers worked. In each of these places, the same diagnosis resounded like a macabre echo repeating itself, postponing the solution until a hypothetical future. The doctor we most often visited worked at the ophthalmology hospital in San Diego, just across the border where my father’s sister also lived. His name was John Pentley and he was a good-natured little old man who zealously prepared potions and prescribed eye drops. He gave my parents a greasy ointment to smear into my eye every morning. He also prescribed atropine drops, a substance that dilates the pupil to its maximum size and that made my world dazzle, turning reality into a cosmic interrogation room. The same doctor advised exposing my eyes to black light. For this, my parents built a wooden box that my small head fit into perfectly, then they lit it up. In the background, like a primitive cinemascope, drawings of animals went around and around: a deer, a turtle, a bird, a peacock. This routine would take place in the afternoon. Immediately after that, they would remove the patch. Recounted in this way, it might all sound amusing, but living through it was agonizing. There are people who are forced to study a musical instrument during their childhood, or to train for gymnastic competitions; me, I trained to see with the same discipline others use to prepare for futures as professional athletes.

But sight was not my family’s only obsession. My parents seemed to think of childhood as the preparatory phase in which they had to correct all the manufacturing defects one enters the world with, and they took this job very seriously. I remember the afternoon when, during a consultation with an orthopedist—clearly lacking any knowledge of child psychology—it occurred to him to declare that my hamstrings were too short, and that this explained my tendency to curve my spine as if trying to protect myself. When I look at photos from those days, it seems to me the curvature in question was barely perceptible in profile. Much more noticeable is my expression: a tense smile, much like the smile that can be detected in some of the photographs Diane Arbus took of children in the suburbs of New York. Nevertheless, my mother took it on as a personal challenge to correct my posture, which she often referred to using animal metaphors. And so, from then on, in addition to the exercises to strengthen my right eye, a series of leg stretches was incorporated into my daily routine. My habit looked so much to her like curling into a shell that she came up with a nickname, a term of endearment, which she claimed perfectly matched my way of walking.

“Cucaracha!” she yelled every two to three hours. “Stand up straight!” Or, “Cucaracha, it’s time for your atropine drops!”

I want you to tell me plain and simple, Dr. Sazlavski, if a human being can make it out of such a regimen unharmed? And if so, why didn’t I? If we really look at it, it’s not so strange. Many people during their childhoods suffer corrective treatment in response to nothing more than their parents’ more or less arbitrary obsessions. “Don’t speak like that, speak like this.” “Don’t eat like that, eat like this.” “Don’t do such things, do other such things.” “Don’t think that, think this.” Perhaps therein lies the true rule of the conservation of our species. We perpetuate unto the newest generation the neuroses of our forbearers, wounds we keep inflicting on ourselves like a second layer of genetic inscription.

At about halfway through all this training, an important event took place in our structured family life: one afternoon, not long before summer vacation, my mother brought Lucas into the world, a blond and chubby boy, who took up most of her attention and who was able to distract her from her corrective agenda, for a few months at least. I will not talk too much about my brother. It is not my intention to tell or interpret his story, just as it does not interest me to tell or interpret anyone’s story but my own. Still, unfortunately for him and for my parents, a good part of his life intertwines with mine. Even so, I want to be clear that the origin of this tale lies in the need to understand certain events and certain dynamics that formed this complex amalgam—this mosaic of images, memories, and emotions—that breathes within me, remembers with me, entwines others, and takes refuge in a pencil the way others take refuge in drinking or gambling.

One summer, Dr. Pentley finally announced that we could stop the daily use of the patch. According to him, my optic nerve had developed to its maximum potential. All that was left was to wait until I had finished growing and they would be able to operate on me. Even though nearly thirty years have passed since then, I haven’t forgotten that moment. It was a fresh morning full of sun. My parents, brother, and I walked out of the clinic hand-in-hand. There was a park nearby where we went in search of ice cream, like the normal family we would be—at least we dreamed we would be—from that point on. We could congratulate ourselves; our resistance had won us the battle.

Of the good times I had with my family, I remember in particular the weekends we spent together at our country house in the state of Morelos, one hour outside Mexico City. My father had bought the land just after my brother was born and built the house my mother designed with the help of a prestigious architect. Carried away by who knows what romantic fantasies, they also built a barn and horse stable. But the only animals we ended up having were a German Shepherd and a good number of hens that kept themselves busy laying eggs. As much as I pleaded, I never convinced my parents to buy lambs or ponies. Our relationship with Betty, our weekend dog, was as loving as it was distant. We never felt the responsibility to train her, to take her out for walks, or to feed her, so even though she was affectionate with us, her canine loyalty belonged to the gardener. Behind the farmhouse ran a clear stream where we’d swim and use plastic bags to catch tadpoles and axolotls, those mysterious animals Cortázar might have mythologized in a short story. My brother and I would spend more than five hours a day in the water, wearing rubber boots and bathing suits. Now, thirty years later, it is impossible to swim in that stream; it’s filled with excrement and toxic residue. One of the wonderful things about that house was the abundance of fruit trees, especially mango trees, lemon trees, and avocado trees. When we’d return to the city, we often brought boxes of avocados in the car to sell to our neighbors. My brother and I were in charge of this job, and it was how we scraped together a decent savings to be squandered over the holidays.

Around that time—I must have been starting third grade—I started to develop a reading habit. I began reading a few years before, but now that I had unlimited access to the clear universe—to which belonged the words and pictures of children’s books—I decided to take advantage of it. I mostly read short stories, but also a few longer books by the likes of Wilde and Stevenson. I preferred suspense or scary stories,

The Picture of Dorian Gray

or

The Bottle Imp.

I often read the equally or even more terrifying stories in my father’s book of Bible legends. There was Princess Salome who beheaded the man she so desired, there was Daniel thrown into the lion’s den. Writing was the natural next step. In my lined notebooks, the French kind, I wrote down tales in which my classmates were protagonists who went to faraway lands where every kind of calamity befell them. Those stories were my opportunity for revenge, and I was not going to waste it. It wasn’t long before the teacher caught on and, moved by some strange solidarity, decided to organize a literary assembly where I could express myself. I refused to read unless I knew beforehand that an adult would stay by my side until my parents came to pick me up that afternoon, since it was very possible that more than one of my classmates would be looking to settle a score after class. As it happened, things turned out differently than I expected. After reading a story in which six of my classmates tragically died trying to escape from an Egyptian pyramid, there was enthusiastic applause. Those who had been featured in the story smugly came up to congratulate me, and those who had not been featured begged me to make them characters in my next tale. That was how, little by little, I earned my particular place at school. I had not stopped being marginalized, but it wasn’t oppressive anymore.

It was the seventies, and my family had embraced some of the prevailing progressive ideas of the time. I went to one of the few Montessori schools in Mexico City (today there’s one on every corner). I know that in those days there were institutions where kids could literally do whatever they felt like. They could set their classrooms on fire and not go to jail or suffer any severe punishment. In my school, we had neither absolute freedom nor stifling discipline. There were no blackboards, no desk chairs set up to face the teacher who, naturally, did not answer to that name, but to “guide.” Each kid worked at a real table—a desk that was all ours, at least for a year—on which we were allowed to leave distinctive marks, drawings and stickers, so long as we didn’t damage the desks beyond repair. Against the walls were bookcases and shelves where we kept our work supplies: wooden jigsaw puzzles of maps with all the world’s countries and flags; multiplication tables that looked like Scrabble boards; textured letters; bells of various sizes; geometric shapes made out of metal; laminated papers with different parts of the human anatomy and their names, to mention a few. Before we could use anything, we had to ask our guide for instructions. It didn’t really matter what we did during the morning, we just had to work on something, or at least pretend to work. A few times a year there were parties for all the families, and then you could really measure the havoc the seventies had wreaked. Guests at these parties included kids whose parents lived in three-way partnerships or other polygamous situations, and instead of feeling ashamed, they flaunted it. The names of some of my classmates give another eloquent vestige of those years. Some of them reflected ideological leanings, like “Krouchevna,” “Lenin,” and even “Supreme Soviet” (we nicknamed him “the Viet”). Others spoke to religious beliefs, like “Uma” or “Lini,” whose full name honored India’s snake of cosmic energy. Others, still, spoke to more personal devotions, like “Clitoris.” That was the name of a lovely and innocent girl, the daughter of an infrarealist writer, who did not yet comprehend the wrong her parents had done her and who, to her misfortune, didn’t have a nickname.