The Bohemian Girl (2 page)

Authors: Frances Vernon

MICHAEL MARTEN:

I found

Westmarch

very difficult to cope with as her literary advisor, but Frances was absolutely determined to write it. It was almost like a reversion to the sorts of first drafts she’d written as a young teenager. But there was something in there that she had to get out, about this business of male and female. She had questions about gender. There was an element, I think, that she thought she ought to have been a boy. Whether this was a consequence of her father wishing for a

son in order to inherit the title is a moot point. I don’t suppose her father consciously made her feel that, far from it. But he did regret that he didn’t have a son, there’s no doubt.

SHEILA VERNON:

Johnnie left Sudbury divided between the girls. But a place like that has gone on for generations by always going to a son. Yes, Frances did once say something to the effect of her having lost out on that by being a girl. Men do have more power in the world, still. And Frances didn’t like that – she found it difficult.

Michael has always said that most of Frances’s inner world is probably in

Westmarch

. Janna said she thought Frances wanted to be a homosexual man, because she wanted sex with men, but to be a man. For a woman that is usually very straightforward, but not for Frances, I’m afraid, sadly.

MICHAEL MARTEN:

Frances suffered from depression. She saw a psychotherapist for the last five or so years of her life, and sometimes she’d feel it helped. Maybe it delayed the outcome.

SHEILA VERNON:

I always saw a lot of her, and did what I could. It is a terrible illness. My sister suffered from depression, she died of heart trouble and had other physical problems, but she said to me once that depression was much the worst thing she’d suffered.

MICHAEL MARTEN:

For any outing Frances had to prepare herself, two or three days in advance – psychologically she’d have to work herself up into a state she could deal with. The travel would be difficult – the prospect rather than the actuality. Eventually she decided she ought to overcome her fear of travel and have a holiday. She took herself off to the Lofoten Islands off the coast of Norway, organised it herself. Why she chose those islands I’m not quite sure, they’re pretty dour. She certainly didn’t enjoy herself, or the food. But she did it, it was an accomplishment for her.

As her illness got worse towards the last years, she found going places very trying – having to call a taxi then worrying if it would be late, or come at all, and once it came, worrying that it would get lost. She could become distraught over things that would seem minor to anyone else, it would all get too much very

quickly – and this was a tendency that got much worse. As a child she’d had terrible tantrums, which she learned to control, but nonetheless the desperation behind them was always there. Sheila and John were, I think, very concerned about her.

Over some years she expressed to me a wish to die. She’d say, ‘I wish I was dead,’ or, ‘I don’t know if I can stand it any more.’ There is nothing you can say to that … you don’t dismiss it, but I didn’t feel it was something that ordinary advice or listening could really resolve. I’m sure I wasn’t as helpful as I could have been. But in reality I don’t know what I could have done.

What would be Frances’s final novel,

The Fall of Doctor Onslow

– originally entitled ‘A School Story’ – was inspired by her reading of the memoirs of the writer and homosexual John Addington Symonds, wherein he exposed the commonplace incidence of homosexuality at Harrow School in the1850s, among pupils and indeed between boys and senior staff.

MICHAEL MARTEN:

Onslow

was based on a true story about a headmaster at Harrow, who was effectively blackmailed or bludgeoned by the father of a pupil into leaving the school and wasn’t allowed to accept any preferment in the Church, such that when he tried to a few years later he got set back. It was a very powerful story and Frances managed to convey it very well. It seemed to me her first novels were very good but of a certain type, novels of manners and mores, but they didn’t really go further than that. Whereas I felt that

Onslow

had more depth.

SHEILA VERNON:

Frances’s sense of humour wasn’t commented on. But it’s there in

Onslow

, especially in Doctor Onslow’s wife Louisa, who is a great character, I think. Nothing’s explained to her but she knows quite a lot. When she speaks of Onslow’s devotion to his pupils and then realises what she’s said … And when Onslow says he’s ‘upset over a boy’, she does know there’s something hidden. Or when they go together to a hotel and she comments on their lack of luggage, to which he replies, ‘A clergyman is always respectable …’ Even he has a joke at himself. Frances was very succinct in her writing, including her humour.

MICHAEL MARTEN:

Gollancz, who published

Westmarch

, turned down the first version of

Onslow

. It was a huge blow to Frances, and she was reluctant to rewrite it, but she did, quite considerably. She must have finished it not long before she died. And it was almost as though she had decided it was the work she had to finish, she had no ideas beyond that – and by finishing it, I think she felt released.

Frances died by her own hand on 11 July 1991 after what

The Times

obituarist would describe as her ‘long struggle with depressive illness’. Having promised her psychiatrist not to end her life using pills he’d prescribed for her depression, Frances created a ‘herbal’ concoction, which she took, and then lay down to die, apparently calmly and peacefully.

MICHAEL MARTEN:

It wasn’t sudden, it was a continual worsening. It was a cloud over her and it grew blacker. She seemed less able to escape from the blackness. When it happened I was certainly shocked. But it was not in the least unexpected. And I felt thereafter that nothing would have saved her.

SHEILA VERNON:

I go over and over thinking how we might have done things differently, and probably we should have, you can’t help wondering. But … you just have to live with it as best you can. In a way it was rather like someone with a terrible illness that couldn’t be cured, and you don’t want them to go on and on suffering.

MICHAEL MARTEN:

A few months after Frances’s death I sent ‘A School Story’ back to Gollancz in its rewritten form but they turned it down. I got in touch with her agency Blake Friedmann and asked them to suggest other publishers who might be interested. They sent me a list of about twenty, to whom I sent copies, most of whom turned it down until André Deutsch accepted it. And I think it’s the best of Frances’s novels.

The Fall of Doctor Onslow

was published finally in July 1994. Ben Preston for

The Times

called it ‘a searing indictment of the process of education … tersely written in a style that successfully

captures Victorian restraint and its stifling sensibilities’. In the

Tablet

, Jill Delay reflected that ‘it is difficult to believe when reading it that the author was a child of our times and did not actually live in the middle of the last century: she recreates that world so vividly, with such understanding of its characters, such an ear for its speech, such feeling for its attitudes and taboos’. Lucasta Miller for the

Independent

observed that the novel’s ‘posthumous appearance is both a tragic reminder of what she might have gone on to do, and a testimony to what she did achieve’.

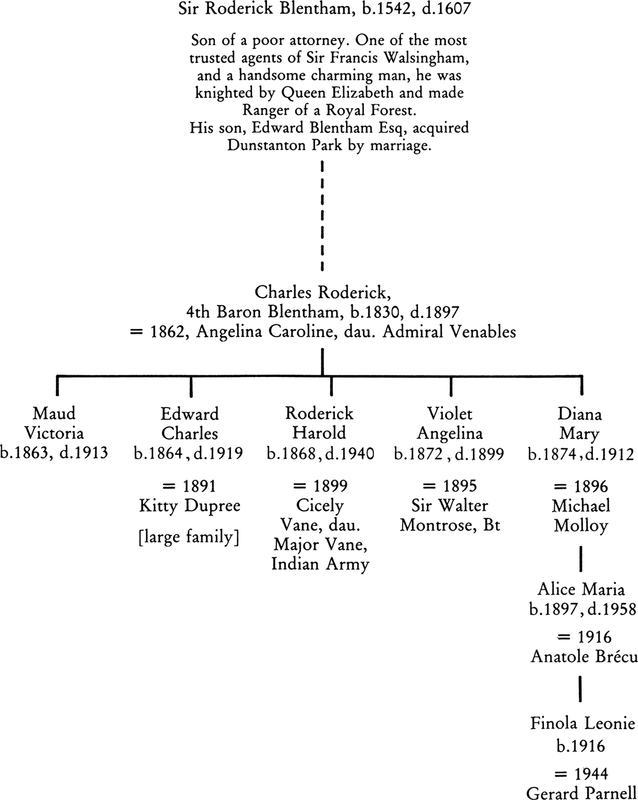

THE BLENTHAMS OF DUNSTANTON PARK

âNurse says your father is connected with Trade,' said Diana. She had an audience of three younger children, who were picking at the remains of potted shrimps and ice-cream.

âHe's not, and I'll pull your hair if you say it again,' said Thomas.

âNurse says your father is â'

Thomas jerked a straggling piece of hair, but not hard enough really to hurt her.

âI was

going

to say something else!' said Diana. âAnd now I shan't tell you what.' She grinned at him, showing a gap in her teeth, when he had expected her to cry.

At that moment, Thomas's fat governess came up.

âI saw, Thomas. I saw that you're incapable of behaving like a little gentleman even for an hour.'

âHe

could

be a gentleman, I s'pose,' said Diana, with her head on one side.

Miss Taplow hesitated, looked at the child, then said: âApologise to Diana, Thomas.'

âI shan't.' The governess slapped his face, and Thomas turned white.

âYou need not stay,' she told him, and pressed her hands to her forehead as he ran off in the direction of the grown-ups' picnic, on the other side of the tall Gothick folly which all had been taken to admire. Miss Taplow slowly followed him, and the nannies, who were guarding the food baskets under an elder tree, looked after her with pursed lips before they started to criticise her: not because of what she had done to Thomas, but because she was a governess and not a nanny.

It was a very hot day, and party discipline had grown lax. At first, the twenty or so children had been arranged in neat circles, and food had been brought to them by the various nurses, and one under-footman from the house. Now, most had had enough to eat and were sitting in idle and irregular positions, while the nannies talked among themselves with their highest collar-buttons undone.

Diana Blentham sat cross-legged on the grass, yawning to herself with one black stocking down. There was a ginger-beer stain on her pink-and-white-striped front, and the bunched back of her skirt was very badly creased. She noticed, as she glanced round, that two of the smaller girls near her were beginning to grow fractious, but their mood did not affect her: she was, as usual, contented but a little bored. She was pleased that Thomas Pagett had pulled her hair, for she liked unusual attentions: she turned her head and saw that he had not come back. Everyone else was occupied in some uninteresting way.

Diana pulled up her stocking, but did not fasten it in place. She got up and walked slowly, in order to attract no attention from the nurses, round the huge clump of rhododendrons which gave the children shade. Before the picnic began she had observed an opening between two lower branches, which had intrigued her, for the rhododendrons at her own home in Kent were not much larger than rose-bushes.

She found the slender gap, pushed aside the branches, and suddenly found herself perfectly enclosed in an open space like a hot and dusty room. Diana stood up, raised her head to the blaze of sky, and hitched her stocking up again. She stuck her finger in her mouth and looked quickly about her.

Stiff leaves and brown flowers with long withered stamens littered most of the ground, and the four low twisting roots were pale as dry earth. When she saw these, Diana realised that the rhododendron was not one miraculously large plant, but several, each of which grew in a different direction. She saw another space ahead, and decided to go further on, and pull apart more barriers.

Diana was six years old, and she had never done anything

so tomboyish as this before. Her own enjoyment of dirt and difficulty surprised her, and she thought of herself as Snow White, deserted in the forest by the huntsman who had just refrained from murdering her. Presently she came to what seemed the last of the dull little glades; she could hear the chink of china and grown-up conversation.

Diana sat down on a low branch and looked through the screen of leaves at the main picnic. At that moment, she saw Thomas's sister Miss Sophie Pagett dart forward with her arm through a young man's, pause, and quickly kiss him. Diana blew out her cheeks to stop a giggle, then frowned: for on her way up to the folly she had seen Sophie Pagett flirting in a very fast way with the local rector. Nurse had even remarked on it.

When the couple passed, Diana leant further forward, and caught a glimpse of her parents. They were standing in the sun, quite some way away, and seemed to be worriedly debating.

She drew back, and began gently to rock up and down on her branch. Then she straddled it, and found that an improvement. The rough thin wood felt strangely pleasant, there between her legs, and she rocked more vigorously, until a piece of broken twig scratched, too hard, at the bare stretch of thigh between her loosened stocking and pushed-up knicker leg. She thought, meanwhile, of kisses, and of rescuing some handsome man from death.

Diana saw the stocky, freckled Thomas Pagett kneeling to her right. She stopped rocking altogether.

âWhat are

you

doing here?' he said.

âRiding!'

âNo you're not.'

They spoke in whispers, because the grown-ups were so near. Thomas got to his feet and came closer. His Norfolks, Diana saw, did not show the dirt as her frock did.

âYou

are

in a pickle,' he said in a slightly affected voice, as though he were acting.

âWhy should I be? I wasn't disobedient,' said Diana. âI wasn't actually told I

couldn't

â do it.'

âBut you know you shouldn't. That's disobedience just the same.'

âNo it's not. Disobedience is different, actually. And what about you? I bet you

were

told you couldn't.'

Thomas ignored this. His eyes were on her bare stretch of pink thigh: he had no brothers or sisters of his own age, and had never seen another person who was not fully covered in his life.

âThis belongs to me,' he said suddenly.

âWhat does?'

âThis place. All of it.'

âIt belongs to your father. Don't tell stories.'

âIt will belong to me. I've got a right to be here.'

âYou're a very rude little boy!' said Diana.

Then she heard her nurse's voice, not very close, saying: âI don't know

where

she can have got to for the life of me. Didie!'

âAnd you're a stupid girl!'

Just as she remembered that her leg was exposed, and took her hand off the branch to pull down her skirt, Thomas moved quickly as a cat and pinched her naked flesh, far harder than he had pulled her hair.

âOw!'

âI'll do it again,' he said, and did it.

âMiss â Diana!' came from far away.

Diana scratched Thomas's face, then scrambled off her branch, hampered by her petticoats, and said in a high voice: âComing, Nurse!' Nurse would not be able to hear that.

âCoward!' said Thomas. His face was red and his eyes were glittering. âI'll kiss you, if, if â'

âI'm going,' said Diana. She made for the other side of the clearing, and Thomas moved awkwardly towards her.

They had been making too much noise. Suddenly, both heard a charming and very close voice.

âGracious, whatever

is

going on in there? James, is it rabbits? Do see!'

Thomas and Diana stood still, their hearts beating foolishly, as the leaves rustled and parted and the moustached Captain

Tremaine, who had kissed Sophie Pagett five minutes before, poked his face through.

âI say! By Jove, I wish

I

could get into the rhododendrons with a girl, young Thomas!'

âI'm not a girl!' Diana said. She was crying, and did not know quite what she meant, except that Captain Tremaine had humiliated her.

âWell, come out then, there's a good girl,' the captain said good-humouredly.

âIs it Thomas in there?' said Sophie Pagett. âOh dear, he

is

a bore.'

Diana stumbled out past the captain, who held the branches apart for her.

âGoodness,' said Sophie when she landed.

âNurse was calling, and I'm going to find her!' Diana said.

The captain said: âWell, we'll both find her then. Come on.'

He picked Diana up as though she were a toy, and sat her on his arm, with a brief wink at Sophie. When he put his hands on her, Diana was too surprised to speak, but a moment later Captain Tremaine saw that she was looking rather sick, and that her lips were working like a baby's. Sophie Pagett looked up inquiringly from under her parasol, then turned to speak to another young lady.

âI say, no need to cry! Come on â a-gallopy, gallopy, gallopy â' Captain Tremaine ran over the lumpy ground up towards the folly, and jolted Diana badly: yet while being jolted, she relaxed. Her tears dried quickly in the heat.

â

Didie

!' said Nurse, who came hurrying up as soon as she saw the young man with a child in his arms. âOh, you naughty girl! Are you all right then? I never saw such a mess. Thank you, sir,' she added.

âHere's a prodigal child,' said the captain, setting her down. âBeen making hay while the sun shines in the rhododendrons with young Thomas. Still, she's going to be a regular beauty, ain't she?' He thought Diana might be in more trouble than she deserved, and so he said this to Nurse although he did not, in fact, think she would be a beauty at all. Addressing Diana herself, he said: âA

Professional

Beauty! I say, won't you like

having your photograph in all the shop windows? I shouldn't wonder if you sold as many copies as Mrs Langtry!' He looked at Nurse, who was herself attractive in a snub-nosed way. She did not laugh, and he raised his monocle. âThe Jersey Lily, you know, Nurse!'

âYou can't sell copies of yourself!' snapped Diana. âYou've only

got

one self.'

*

Nurse scolded Diana well as she led her firmly away from the remains of the picnic to a modest dip in the ground behind a grove of rowan trees. There she began to tidy the child, pulling up her grubby skirt to deal with the fallen stocking and loose knicker-leg. She searched for needle and thread in her pocket.

âI'm sure I don't know what can have come over you, Didie. Naughty as Violet may be, with her pulling faces and all,

she's

never thought of doing just such a thing, I'm sure.' Violet was eight, and Nurse loved her although she was neither as pretty nor as intelligent as Diana. âOld Mr Jenkins used to say, when I was nursery maid, before you came even, that Miss Maud was always wanting to be a little boy, forever climbing trees she was at your age, and ever so mischievous, and now she's giving your Ma funny turns with all her nonsense about I don't know what, and her going to be presented to the Queen, too, not six months from now! I hope

you

won't â' Nurse stopped, and stared at Diana's leg.

âWhat is it?' said Diana, who had quite calmed down during Nurse's lecture.

Nurse looked up. âSit down please, Miss Diana.'

âDon't call me that,' she said. The unease and tearful fright which had first surprised her when Captain Tremaine appeared in the bushes came over her again.

âI'll call you what I like

when

I like. Now â' Nurse pushed back Diana's skirts as far as they would go, and pointed to two fat scarlet pinch-marks on her thigh. âWhat are these? How did you come by them?'

There was a pause.

âT-Thomas pinched me â I hate him! Oh, don't be like that,

don

'

t

!

Why

are you like that, it's

stupid

!'

âHe was alone with you? In the bushes? I thought the Captain was â Miss Diana, don't cry.' Nurse's voice was very low. âDid you pinch him â anywhere? Tell me now!'

âI scratched his face!' cried Diana. âAnd I'm not sorry!'

âYou scratched his face, did you?' Nurse let out a little breath. âNow, Didie, I see you're upset, and I want you to stop crying. See? Now listen to me. Thomas did something very wrong â very wrong â though you're both of you too young to know why. But you knew it was wrong in a way, didn't you? Isn't that why you're crying?'

âYes!' said Diana. She had wanted to pinch him, equally hard, but his rough tweeds had left no flesh exposed for her to pinch.

âIt was horrid, wasn't it, when he did it?'

âYes!' It had certainly been painful for a moment, and she had been very angry.

âWell, it's high time Master Thomas went to school!' Nurse said. She continued: âDidie, if a little boy pinches you in a bad place again â which I trust he won't never have the chance to, not if you keep your stockings up like a lady should! â don't scratch his face. You scream, loud as you can.'

âBut why? I thought it was naughty to scratch people, and â'

âNot when â oh, dear me, if only you wasn't a child! Didie, it's not so bad as all that, not now, but when you're a little older â as old as Miss Maud â you'll never be allowed to be alone with a big boy. A young man I mean. You know that, don't you?'

Diana's eldest sister Maud was seventeen.

âIn case he pinches me?'

âYes.'

âEven if â suppose I wanted him to pinch me, Nurse?'

Nurse took hold of her shoulders. âThat's what would be wrong! Oh, dear, Didie, you mustn't want a â boy to pinch you till you're married. And you won't get married if you let him pinch you before! You

mustn't

ever want him to, it's not what the good Lord intended. And remember it hurts, miss!'

She looked down. âI shouldn't be telling you all this, you're sharp enough as it is, Lord knows, and you'll be asking questions. Don't you ask of your Ma, or you'll be losing me my place!'

âOh!'

âNow, it's nothing, I'm talking foolishness. But don't. Didie, I'm just warning you as I shouldn't.' Nurse paused. âI had a little sister, who'd dead now, and she came to a bad end â a very bad end â through letting people pinch her in an unseemly sort of way.'