The Book of Basketball (40 page)

Read The Book of Basketball Online

Authors: Bill Simmons

Tags: #General, #History, #Sports & Recreation, #Sports, #Basketball - Professional, #Basketball, #National Basketball Association, #Basketball - United States, #Basketball - General

(And if the Lakers had won the ’63 Finals, then I’d be pleading his case. But they didn’t.)

Kareem Abdul-Jabbar (1972)

Here we have the league’s reigning alpha dog and MVP averaging a career-best 34.6 points, 16.8 rebounds and 4.6 assists per game for a 63-win team. From 1969 to 2008, that’s the single greatest statistical season by a center; Young Kareem was also the best defensive center of that decade other than Nate Thurmond. So I can’t kill this pick. But we should mention—repeat:

mention—

that the Lakers broke two records (69 wins, 33 straight) en route to Jerry West’s first championship. Unfortunately, nobody could decide which Laker was more responsible: West (26–4–10, led the league in assists) or Wilt (15–19–4, 65% FG, led the league in rebounds)? Check out

the bizarre voting, the only time that one team placed two of the top three: Kareem: 581 (81–52–20); West: 393 (44–42–47); Wilt: 294 (36–25–39).

This raises an interesting question: Should a special “co-champs” choice be added to the ballot for every season with a memorable team that didn’t have an identifiable alpha dog? The ’58 Celtics (Cousy and Russell), ’70 Knicks (Reed and Frazier), ’72 Lakers (West and Wilt), ’73 Celtics (Hondo and Cowens), ’97 Jazz (Stockton and Malone), ’01 Lakers (Shaq and Kobe), ’05 Heat (Shaq and Wade) and ’08 Celtics (Pierce and Garnett) all qualify and solve many of the problems in this chapter. The ’72 season was the ultimate example: Kareem was the singular MVP and West and Wilt were co-MVPs. Right? (You’re shaking your head at me.) Fine, you’re right. Dumb idea.

Bill Walton (1978)

Even an unbiased observer would admit that for the eleven months stretching from April ’77 through February ’78, the Mountain Man was the greatest player alive and pushed that Portland team to surreal heights.

31

Right as that team was cresting, the February 13, 1978,

Sports Illustrated—

one of the watershed issues of my childhood because of an insane Sidney Moncrief tomahawk dunk on the cover—ran an extended feature on the Blazers in which Rick Barry called them “maybe the most ideal team ever put together.” Everything centered around Walton (19–15–5, 3.5 blocks), the next Russell, an unselfish big man who made teammates better and even shared killer weed with them. Two weeks after the

SI

story/jinx, the big redhead injured his foot and didn’t return until the Playoffs, when he fractured that same foot in Game 2, killing Portland’s playoff hopes and leading to his inevitable messy departure.

32

Now …

It’s hard to imagine anyone qualifying for MVP after missing twenty-four games, much less taking the trophy home. But we’re talking about an

especially loony season, as evidenced by our rebounding champ (Mr. Leonard “Truck” Robinson) and assists champ (the one, the only, Kevin Porter). Kareem sucker-punched Kent Benson on opening night, missed 20 games and struggled for the remainder of the season. Erving submitted a subpar (for him) season.

33

The strongest candidates were George Gervin (27–5–4, 54% FG) and David Thompson (27–5–5, 52% FG), both leading scorers for division winners who weren’t known for their defense. Guards weren’t supposed to win MVPs back then; only Cousy and Oscar had done it, and as much as we loved Skywalker and Ice, they weren’t Cousy and Oscar. So Walton drew the most votes (96), Gervin finished second (80.5), Thompson third (28.5) and Kareem fourth (14); a dude from Venice named Manny, the league’s unofficial coke dealer, finished fifth (10).

34

The case for Walton: He played 58 of the first 60 games and the Blazers went 50–10 over that stretch. He missed the next 22 games and the Blazers stumbled to an 8–14 finish (hold on, huge “but/still” combo coming up),

but

they

still

finished with a league-best 58 wins and clinched home court for the Playoffs. So yeah, Walton missed 24 games

and

had an abnormally profound impact on the regular season, winning 50 games during a season when only two other teams finished with 50-plus wins: Philly (55) and San Antonio (52).

The case against Walton: Borrowing the Oscars analogy, would you have accepted the choice of

No Country for Old Men

for Best Picture if the movie inexplicably ended with thirty-five minutes to go? (Actually, bad example—that would have been the best thing that ever happened to

Old Men.

I hated everything after we didn’t see Josh Brolin get gunned down.

35

You’re never talking me into it. I hated English majors in college and I hate

movies that are vehemently defended by English majors now. The last twenty minutes sucked. I will argue this to the death.) Take two: Would you have accepted

The Departed

as Best Picture if the movie inexplicably ended with thirty-five minutes to go and you never found out what happened to DiCaprio or Damon? No.

Ultimately it comes down to one thing: even if Walton and the Blazers only owned 70 percent of that season, still, they

owned

it. Nobody else stood out except Kareem (for clocking Benson), Kermit Washington (for clocking Rudy T.), Dawkins (for breaking two backboards), Thompson/Gervin (for their scoring barrage on the final day), the Sonics (who started out 5–22 and staged a late surge to make the Finals) and Manny (the aforementioned coke connection that I made up, as far as you know). That’s good enough for me—I’ll take 70 percent of a Pantheon season over 100 percent of a relatively forgettable season. I’m signing off. We’ll make an exception here with all the missed games. Just this once.

Tim Duncan (2002)

The ’02 season featured a ballyhooed battle between Duncan (a career year: 25–13–4 plus 2.5 blocks and superb defense) and Jason Kidd (15–7–10 and superb defense), with Kidd owning the season because of a much-argued-about trade the previous summer, when Phoenix swapped Kidd to New Jersey for Stephon Marbury a few months after Kidd was charged with domestic assault.

36

Energized by the change of scenery, Kidd led the perenially crappy Nets to 52 wins, swung the New York media behind him and stood out mostly for his unselfishness and singular talent for running fast breaks, as well as his attention-hogging wife, Joumana, who brought their young son courtside and seemingly knew the location of every TV camera.

37

Maybe Kidd’s ’02 season didn’t match his ’01 season in Phoenix (17–6–10, 41% FG), but mostly by default, Kidd became the featured

story in a historically atrocious Eastern Conference,

38

leading to one of the closest (and dumbest) MVP votes ever: Duncan: 952 (57–38–20–5–3); Kidd: 897 (45–41–26–9–3); Shaq: 696 (15–38–40–25–5); T-Mac: 390 (7–5–28–45–10).

Um … why was this close? Duncan topped 3,300 minutes, 2,000 points, 1,000 boards, 300 assists and 200 blocks, carried the Spurs to a number two seed in the West, didn’t miss a game and had a greater effect on his teammates than anyone else but Kidd. Look at his supporting cast: Bruce Bowen, Antonio Daniels, Tony Parker, Malik Rose, Danny Ferry, Charles Smith, a past-his-prime David Robinson, a pretty-much-past-his-prime Steve Smith and a past-being-past-his-prime Terry Porter. That’s a 58-win team? Had you switched Duncan with someone like Stromile Swift, the Spurs would have won 25 games. Meanwhile, the Lakers swept the Nets in the Finals in a mismatch along the lines of Tyson-Spinks, Ryan-Ventura and any

Melrose Place

cast member acting in a scene with Andrew Shue.

39

That’s when we all realized, “We knew the East was bad, but we didn’t know it was

that

bad!” That a 39 percent shooter for a 52-win team in a brutal conference nearly stole the MVP from the greatest power forward ever during his finest statistical season for a 58-win team … I mean, you can see why I don’t trust the MVP process so much.

(By the way, Shaq retained alpha dog status this season, remaining on cruise control for 82 games—partially because he was lazy, partially because this was the year when he fully embraced his abhorrence of Kobe—before turning it on for the playoffs and averaging a 36–12 in the Finals. From there, he spent the entire summer eating. In fact, I think he grilled one of the Wayans brothers, covered him in A-1 sauce and ate him at one point.)

CATEGORY 2:

FISHY AND ULTIMATELY NOT OKAY

Bob Pettit (1959)

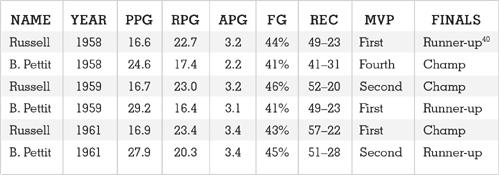

Again, any time you’re putting the MVP in the hands of mostly white players competing in an era marred by racism and resentment toward black athletes, you’re definitely hitting a few speed bumps. The league had an unwritten “only one or two blacks per team and that’s it” rule in the fifties; even as late as 1958, the Hawks didn’t have a single black player. So it’s a little suspect that Pettit (a white guy) won the ’59 MVP award in a landslide over the league’s reigning MVP and most important player (Russell, a black guy) when 90 percent of the votes were from whites. Check out their numbers during ’58 and ’61 (when Russell won) and ’59 (when Pettit won), factor in their defensive abilities (Pettit was mediocre; Russell was transcendent), then help me figure a coherent explanation for Pettit nearly tripling Russell in the ’59 voting that doesn’t involve a white hood.

Here are the numbers:

Here’s how the ’59 voting shook out: Pettit: 317 (59–7–1); Russell: 144 (10–25–29); Elgin: 88 (2–20–18);

41

Cousy: 71 (4–11–18); Paul Arizin: 39 (1–7–13); Dolph Schayes: 26 (1–6–3); Ken Sears: 12 (1–1–4); Cliff Hagan:

7 (1–4–0); Jack Twyman: 7 (0–1–4); Tom Gola: 3 (0–1–0); Dick McGuire: 3 (0–1–0); Gene Shue: 1 (0–0–1).

Here’s what happened in the ’59 playoffs: Elgin’s 33-win Lakers team shocked Pettit’s Hawks in the Western Finals, then were swept by the Celtics in the Finals.

You know how the host of

The Bachelor

always says going into commercial, “Coming up, it’s the most dramatic rose ceremony

ever

”? Well, this was the most racist MVP voting year

ever.

You had Pettit’s bizarre landslide win (really, six times as many first-place votes as Russell?), half the league ignoring Elgin, the Cooz stealing four of Russell’s first-place votes and four other white players (Arizin, Schayes, Sears, and Hagan) unaccountably earning first-place votes. You can’t even play the “Pettit was a sentimental choice” card because he’d already won in ’56. And if you’re not buying the race card, remember the times (pre-MLK, pre-JFK, pre-Malcolm, pre-desegregation), the climate (in baseball, the Red Sox signed their first black player in ’59: the immortal Pumpsie Green), and stories like the following one from

Tall Tales

about the Lakers playing an exhibition game in Charleston, West Virginia. Their three black players (Baylor, Boo Ellis, and Ed Fleming)

42

were not allowed to check into their hotel or eat anywhere in town except for the Greyhound bus station. Here’s how Hot Rod Hundley and Baylor remembered the incident:

Hundley: “The people who put on the game wanted me to talk to Elgin about playing. After pregame warmups, I went into the dressing room and he was sitting there in his street clothes. I said, ‘What they did to you isn’t right. I understand that. But we’re friends and this is my hometown. Play this one for me.’ Elgin said, ‘Rod, you’re right, you are my friend. But Rod, I’m a human being, too. All I want to do is be treated like a human being.’ It was then that I could begin to feel his pain.”

Baylor: “A few days later, I got a call from the mayor of Charleston and he apologized. Two years later, I was invited to an All-Star Game there, and out of courtesy I went. We stayed at the same hotel that refused us service. We were able to eat anywhere we wanted. They were beginning to integrate the schools. Some black leaders told me that they were able to use what had happened to me and the other black players to bring pressure on the city to make changes, and that made me feel very good. But the indignity of a hotel clerk acting as if you aren’t there, or people who won’t sell you a sandwich because you’re black … those are the things you never forget.”

So yeah, things eventually did change; some of those changes were already in motion in 1959. But Russell and Baylor were pushing the sport in a better direction and some of their peers weren’t, um,

down

with the new movement yet. That’s the only explanation for the lopsided voting. I don’t mean to come off like Sam Jackson screaming, “Yes, they deserved to die and I hope they burn in hell!” in

A Time to Kill

, but at the same time, bigotry affected the ’59 vote and that’s that. Russell was the MVP.

Wes Unseld (1969)

As a rookie with the Bullets, Unseld made a name for himself with bone-crushing picks and crisp outlet passes, averaging a 14–18 and shooting 47% for a 57-win team. Willis Reed played a similarly valuable role in New York, averaging a 22–14 and shooting 52% for a 54-win Knicks team, but Unseld’s total in the MVP voting more than doubled Willis (310 to 137) and Unseld grabbed first-team All-NBA honors. In the first round of the ’69 playoffs, Reed and the Knicks swept Baltimore and everyone felt stupid.

43