The Book of the Dun Cow (20 page)

Read The Book of the Dun Cow Online

Authors: Walter Wangerin Jr.

Tags: #Speculative Fiction, #FICTION/General

“Speaks a Rooster, ha! A Rooster once in the Dog's mouth, too, ha! Ha, ha, to you, Rooster! Is Double-u's what dig; but Roosters only flutter-gut about. Go find the Netherworld without a digger Double-u!”

“Just wait, you slow mope. I'll see that Dog before you do. I'll find the hole into Wyrm's caverns before you scratch surface!”

“Ha!”

As it happened, then, Pertelote fell asleep before either of these adversaries did. Far into the night they held lively conversation with one another, pointing out absurdities in each other's character and promising mighty promises, each to be fulfilled at an early date.

But the sound of their brave chatter was good in Pertelote's ears. She had been successful. She slept peacefully.

Here ends the twenty-eighth and final chapter of the story about Chauntecleer and the keeping of Wyrm

.

Authors resist the categorization of their works. It's too much like shaving the river: causing a narrower and narrower flow of meaning and thereby a swifter rush of contemplative thought. The many currents of a good novel are lost when only one or two are accounted the whole of the motion, and a reader's response can't help but be made the more shallow.

Since its publication twenty-five years ago,

The Book of the Dun Cow

has been grouped among works and types with which it shares certain literary characteristics but from which it diverges too much to share the same category completely.

For those who might hereafter study the novel, allow me to offer a brief listing of the sources and influences that directed my writing.

Chaucer's “The Nun's Priest's Tale” was my immediate entrance into the “beast fable” genre, whence the basic characteristics of Chauntecleer and Lord Russel the Fox. But those are types, and the beast fable has ever been a moralizing thing, an instructing thing, since Hesiod's poem about the hawk and the nightingale, through Aesop, Phaedrus, John Gay in England, and Joel Chandler Harris in America. Chaucer exaggerated these elements. The modern novel requires greater complexity and less overt moralizing.

The “Beast Epic,” though it often parodied serious epics while

Dun Cow

takes the serious epic seriously, gave a broader scope to my work. Too, this genre developed a sharply realistic observation, comparable to my own use of the actual habits of animals which might capture and intensify the actual behaviors of human beings. I did, in fact, raise chickens, fought rats, knew dogsâand did zoological research into these creatures as well as study zoology's unrecognized cousin, the bestiaries of the Middle Ages (the

Physiologus

in its many imitations; the

Exeter Book)

.

Early church fathers produced series of sermons called

De Hexameroi

, “On the Six Days” of creation, in which theological reasons for the physical details of God's handiwork are explained: the human brow is to protect the eye-beams as they seek truth in the world. This material, assuming that the mind and the purposes of the Creator might be read in creation itself, gave context to my own attitudes in writing a book about animals in a raining creation.

Medieval cosmologies did more than give me a well-constructed metaphor for the world of my novel; they established a weltanschauung, a thematic vision of elemental relationships spiritual, communal, natural: a cosmic

order

to things.

As Milton chose epic to frame the grand drama of humankind, so I used elements of that genre for

Dun Cow

(councils, bees, battles) as well as his elevated themes of good and evil; but the tone could not have imitated his noble sonority, his earnest sobriety. Our times call for humor, for a sort of self-deprecating use of the genre that once upon a time defined whole peoples and their cultures. Presently we are too diverse to think a single story defines us.

Romance (especially as exemplified by the language and the final battles in Mallory's

Morte Darthur

) shaped my own conceptions and developments of physical warfare in the three battle sequences of the book. At the same time I drew insights and images from the book

Face of Battle

, by John Keegan.

Biblical patterns, narratives, types scarcely need mentioning.

From its first conception, I knew the novel's general protagonist would be the “Community of the Meek,” Chauntecleer's Coop and all things related to it. I knew, too, that there must be a terrible antagonist set against this, in order that I might, in the process of writing the book, investigate how such communities are affected byâand do respond toâexternal evils of overwhelming force.

But what the evil should be took some time to decide. I discarded an evil made up of natural animals (as the Coop is “natural”) since (1) that kind of trouble would arise within the Coop anyway, and since (2) I sought an evil outside our common living conditions. Likewise, I thought about and discarded introducing humans as the evil (as in

Watership Down)

, since readers should have nothing else to identify with than the Coop. Finally, I chose certain mythological figures of evil which already were based upon fanaticizedâbut nonetheless believedâcharacterizations of beasts, snakes, basilisks, the cockatrice. This had the authenticity and the tight complexity produced by countless generations of human attention, imagination, retelling; it was greater than anything I could myself inventâand so, for example, the birth of Cockatrice as described in the novel is taken from a medieval description of the births of such creatures. But Wyrm (that name taken from the Old English, its word for something like a dragon in

Beowulf)

is modeled on the Loki Monster and shaped according to my own designs.

What

The Book of the Dun Cow

is notânor was ever intended to beâis an allegory. Allegories ask an intellectual analysis: “This means that,” “This detail in the story is equivalent to that fact, that doctrine, that idea

outside

the story.”

The Book of the Dun Cow

invites experience. Allegories are reductive of meanings; they bear a riddling quality; they demand the question, “What does this mean?” But a good novel is first of all an event; as distinguished from the continuous rush of many sensations and the messy overlapping experiences of our daily lives, it is a

composed

experience in which all sensations are tightly related, for which there is a beginning and an ending, within which the reader's perceivings and interpretations are shaped for a while by the internal integrity of

all

the elements of the narrative. Meaning devolves from (and must follow) the reader's experience. Meaning, therefore, springs from the relationship between the reader and the writing. Should I, the author, ever state in uncertain terms what my book means, it would cease to be a living thing; it would cease to be the novel it might have been, and would rather become an illustration of some defining, delimiting concept. Sermons do that well and right properly. Novels in which themes demand an intellectual attention can only be novels in spite of these didactic interruptions.

The Pilgrim's Progress

works best as a novel when we ignore its allegorical nature until first we have experienced wholly its romantic nature.

Having, in

The Book of the Dun Cow

, investigated evils external to human systems I turned next, in its sequel, to the evils internally present within communities and their individuals.

The Book of Sorrows

pays close attention to the motives of society's leaders and the effects of their behaviors upon the societies they lead.

It is never enough merely to know and discuss the evils to ourselves. The Chauntecleer who leads his Coop against Wyrm, if he does not examine and know his own character, shall become the evil within the Coop.

If

Dun Cow

drove me to a sacrifice for the saving of a community, then

Sorrows

brought me to another act, more personal, for the solving of our own internal sinnings: forgiveness.

Walter Wangerin, Jr.

June 4, 2003

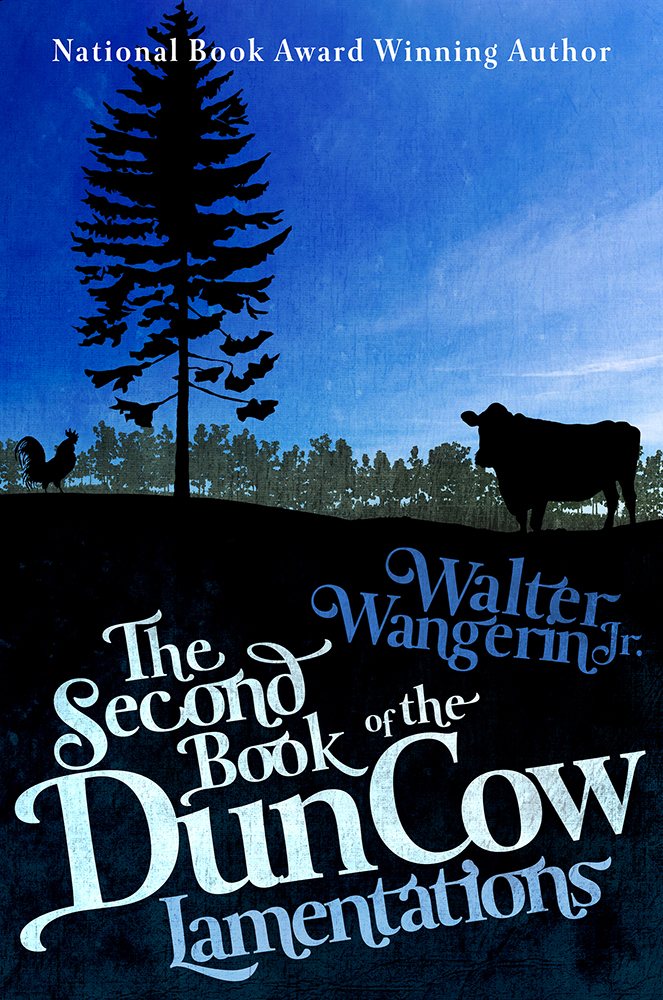

The Second Book of the Dun Cow:

Lamentations

PART ONE

Russel, the Fox of Good Sense

[One]

In which the Fox Strives to Talk

Russel had fought as bravely as any other Creature in the battle against Wyrm and all his evil Basilisks. Serpents were the Basilisks, three feet long, as black as licorice, thick and dimpled when they writhed. They crawled the ground like little kings with their heads raised up on the loops of their necks. Their eyes were fiery and their flesh moist with poisons. Russel had dashed among them, cutting sharp corners with the snap of his bushy tail, talking, talking, challenging the enemies with a babble of well-constructed sentences. The Fox had rolled in the oils of the rue plant whose stench caused the Basilisks to tighten into helpless balls.

“I route, not to say

route

you by the tens and the twenties, for I am clever and hearty and vulpine, am I!”

But then he bit a fat Basilisk. His canaines burst the serpent, and the serpent wrapped itself round the Fox's snout, and though the Fox dispatched it altogether, its poisons burned him, mouth and tongue and lips and his pointy nose back to the eyeballsâand that was that for Russel's hostilities.

He rubbed his snout with the joints in his forepaws, but only succeeded in smearing the poisons deeper and deeper into his fur, down to the flesh, and then it was that all the flesh of his face stung and, because of his furious rubbing, began to bleed.

“No pity,” Russel managed to say. “No cause to pity a Fox, because his wounds, O dear Lord Chauntecleer, they are the wounds of his own folly.” Blood scored the gaps between the Fox's teeth. But he could not stop talking. His words sprayed mists of blood. His sentences stretched and wracked his lips. But his love of talk was greater than his pain. For Russel, to talk was to be aliveâwas to

be.

By talk he had taught tricks to Pertelote's three little Chicks. By talk he had instructed Mice in the ways of Coop-life. Russel was ever a charming orator.

“Fight on,” he called to the warrior Creatures of the Coop. “Glorify the day, and triumph by the moonlight!”

Then, when the war had indeed been won, the beautiful Hen Pertelote found the Fox lying inert in the grass, his jaws and his mouth and his muzzle swollen and hardening. Puss and a watery blood seeped through the scabs.

“Russel,” Pertelote said with genuine compassion. “What did they do to you?”

The Fox rolled his eyes up to the Hen. He said, “Umph,” and “Pumffel.”

“Don't talk,” she said. “I'll get some salve forâ“

Russel said, “No pity, not to say pity, for a Fox who lost good sense.”

When he spoke the scabs cracked and the blood gushed.

“Please!” Pertelote begged, wiping the blood with her white wings. “Don't talk! You'll infect yourself.”

“All is well,” Russel said. “Everything is well. The victory, why, the victoryâ“

Chauntecleer crowed, “Shut up, you idiot! What's the matter with you?” He leaped into the air, beat his wings, and alighted directly in front of Russel's nose. “Do you

want

to die?”

“But, you see, if I can't talk, well, thatâs a sort of dying.”

Chauntecleer took the Fox's jaws between his talons and shut them in an iron grip.

By the second week of his convalescence Russel wore a carapace from his eyes to the tip of his nose. “Mmmm!” he mewed, his eyes like boiled eggs. “Mmm. Sss,” and “Mm-ffle.” Fleas had begun to scurry at the roots of his fur.

Pertelote suffered for the sake of her patient. His snout and his breath were foul in her nose. “Oh, Russel,” she said softly in his ear. “We can wait to hear you again. Can't you wait to talk?”

Russel tried to obey. But the word that popped into his brains popped immediately out of his mouth.

He said, “Presenting you with thanksgivings, pretty Pertelote.” The carapace cracked. The wounds separated, and Russel's

P'

s (

P

resenting,

P

retty,

P

ertelote) sprayed blood.

Wearily Chantecleer said, “For the love of God, you miserable faucetâshut up.”

Two Hens walk in a yellow field: white under the sunlight, pure beneath a deep blue sky.

The one in the lead is adorned with a burst of crimson feathers at her throat. The one who follows is fat. Her comb is vestigial, an abrupt, pinch, surrounded by pink baldness on her skull. She huffs and puffs to keep up. This one thrusts her head forward with every waddling step. Her wings hang loose in order to cool her corpulence. She is drenched with sweat.

“There,” says the beautiful Pertelote. She gestures with her beak. “There, Jasper. Do you see it? We've found what we came for.”

“See, Missus? Not to be doubting you. Pardon me and all thatâbut it ain't no more'n a tree.”

“Look beyond the tree. To the green vegetation thick on the ground. There are the medicinals. Let's go.”

Pertelote spreads her wings to fly.

Jasper says, “Butt pimples.” This is the way the fat Hen swears. “Chicken dribbles. Ain't I already gone gut-weary, Missus?”

Pertelote laughs and sails forward.

Jasper grunts. She generally hates laughter, for she believes that most of it is aimed at her.

Fatty, fatty, two by fourâ¦.

Jasper is of the opinion that Animals are mean and fully of mockery.

Couldn't get through the kitchen door

â¦. Mockery wants a pecking, for pecking gets respect.

Pertelote calls backward, “And don't I love you, Jasper?”

Well. And so. And all right. The fat Hen is mollified. But unable to make a true flight, she plods after her Missus.

The first patches of the green vegetation is jimson weed. Beyond that is a tough tangle of juniper.

Under the jimson Pertelote looks for dark datura.

Jasper comes behind, cussing. “Goat pee.”

Pertelote brings up a warty-green thornapple and tosses it back to Jasper:

Thunk!

“Fox farts.”

Suddenly Pertelote pauses. She tips her head, listening. She thinks she heard a rustling under the juniper. She shakes her head and she finds another thornapple and tosses this one too at Jasper.

Thunk!

“Hen's teeth, Missus! Is it for knocking down a sister Hen that you throw bombs at her?”

Pertelote says, “Not bombs, Jasper. Sacred datura. There isn't a stronger Hen than you, nor a better one to carry the medicine back.”

“Well, folderol,” Jasper swears. “Chicken livers in vinegar juice I say. If that's what you wanted, I'm gone, and no skin off'n my beak.” She tucks the thornapples one under each wing and leaves.

Again Pertelote hears the rustling ahead of her. She knows the sound. It fills her with sympathy. Someone has isolated herself. Someone is hiding under the juniper.

Pertelote bends to pick berries. She speaks as if to the air. “The sacred datura will put poor Russel to sleep. And it's the juice of the juniper will bathe his infections.”

Picking berries. Picking berries. Giving her hidden sister time to adjust to her coming.

Pertelote begins to sing:

“My sister, she left us for sorrow,

Poor sparrow.

We craved her return by the morrow,

Black laurel.

When, when will she come forward?”

Pertelote has made a small heap of berries. She stands and raises her head and sings that first line again, but with one variation: “Chalcedony left me in sorrow.”

A thin voice peeps, “Sorrow? Not never did I hope to sorrow my Lady. No, not never.”

“Of course not. Chalcedony would never mean to sorrow my heart.”

Chalcedony falls silent. Even the rustling ceases. Then she says, “Maybe my Lady can go away now?”

“Oh, my sister, why should I go away?”

Again, a long silence.

When Chalcedony speaks again, her voice is moist with tears. “Private matters. Unhappy matters.”

“Lady of Sorrows,” Pertelote murmurs, “why are you sad? Perhaps I can comfort you.”

Now Chalcedony begins to sob. “Hoo, hoo, hoo.”

Pertelote spreads the juniper branches aside. Chalcedony is gaunt. In heaven's name, what has she been doing here, alone?

Then the skinny Hen draws back, and Pertelote sees an egg lying before her.

Chalcedony says, “I'm sorry. I am that, my Lady. I didn't never want to cry.”

“Sister! You've begun to bring a child to birth.”

“I never couldn't lay another since the Rat kilt the first, and that the first of all I ever made. But I says to my soul, âAnd why mayn't Chalcedony be layin' an egg like any other?'”

“A lovely little egg. Unblemished.”

“Oh, Lady, oh Lady.” The thin Hen gives herself over to heavy sobs and tears. “But I been sittin' broody on my perfect egg weeks and weeks, and the pretty bairn can't hatch. Chalcedony, she's got a motherly heart, but never no baby to mother.”

Now Pertelote sits down beside her sorrowful sister and lays a wing over her back.

“It is time,” she says. “It is surely time to cry.”

The Second Book of the Dun Cow: Lamentations

is available from

all major ebook retailers

.