The Book Thief (24 page)

Authors: Markus Zusak

Tags: #Fiction, #death, #Storytelling, #General, #Europe, #Historical, #Juvenile Fiction, #Holocaust, #Children: Young Adult (Gr. 7-9), #Religious, #Books and reading, #Historical - Holocaust, #Social Issues, #Jewish, #Books & Libraries, #Military & Wars, #Books and reading/ Fiction, #Storytelling/ Fiction, #Historical Fiction (Young Adult), #Death & Dying, #Death/ Fiction, #Juvenile Fiction / Historical / Holocaust

“Papa!”

Liesel, at the

high end of eleven, and still rake-skinny as she sat against the wall, was

devastated. “I’ve never been in a fight!”

high end of eleven, and still rake-skinny as she sat against the wall, was

devastated. “I’ve never been in a fight!”

“Shhh,” Papa

laughed. He waved at her to keep her voice down and tilted again, this time to

the girl. “Well, what about the hiding you gave Ludwig Schmeikl, huh?”

laughed. He waved at her to keep her voice down and tilted again, this time to

the girl. “Well, what about the hiding you gave Ludwig Schmeikl, huh?”

“I never—” She

was caught. Further denial was useless. “How did you find out about that?”

was caught. Further denial was useless. “How did you find out about that?”

“I saw his papa

at the Knoller.”

at the Knoller.”

Liesel held her

face in her hands. Once uncovered again, she asked the pivotal question. “Did

you tell Mama?”

face in her hands. Once uncovered again, she asked the pivotal question. “Did

you tell Mama?”

“Are you

kidding?” He winked at Max and whispered to the girl, “You’re still alive,

aren’t you?”

kidding?” He winked at Max and whispered to the girl, “You’re still alive,

aren’t you?”

That night was

also the first time Papa played his accordion at home for months. It lasted

half an hour or so until he asked a question of Max.

also the first time Papa played his accordion at home for months. It lasted

half an hour or so until he asked a question of Max.

“Did you learn?”

The face in the

corner watched the flames. “I did.” There was a considerable pause. “Until I

was nine. At that age, my mother sold the music studio and stopped teaching.

She kept only the one instrument but gave up on me not long after I resisted

the learning. I was foolish.”

corner watched the flames. “I did.” There was a considerable pause. “Until I

was nine. At that age, my mother sold the music studio and stopped teaching.

She kept only the one instrument but gave up on me not long after I resisted

the learning. I was foolish.”

“No,” Papa said.

“You were a boy.”

“You were a boy.”

During the

nights, both Liesel Meminger and Max Vandenburg would go about their other

similarity. In their separate rooms, they would dream their nightmares and wake

up, one with a scream in drowning sheets, the other with a gasp for air next to

a smoking fire.

nights, both Liesel Meminger and Max Vandenburg would go about their other

similarity. In their separate rooms, they would dream their nightmares and wake

up, one with a scream in drowning sheets, the other with a gasp for air next to

a smoking fire.

Sometimes, when

Liesel was reading with Papa close to three o’clock, they would both hear the

waking moment of Max. “He dreams like you,” Papa would say, and on one

occasion, stirred by the sound of Max’s anxiety, Liesel decided to get out of

bed. From listening to his history, she had a good idea of what he saw in those

dreams, if not the exact part of the story that paid him a visit each night.

Liesel was reading with Papa close to three o’clock, they would both hear the

waking moment of Max. “He dreams like you,” Papa would say, and on one

occasion, stirred by the sound of Max’s anxiety, Liesel decided to get out of

bed. From listening to his history, she had a good idea of what he saw in those

dreams, if not the exact part of the story that paid him a visit each night.

She made her way

quietly down the hallway and into the living and bedroom.

quietly down the hallway and into the living and bedroom.

“Max?”

The whisper was

soft, clouded in the throat of sleep.

soft, clouded in the throat of sleep.

To begin with,

there was no sound of reply, but he soon sat up and searched the darkness.

there was no sound of reply, but he soon sat up and searched the darkness.

With Papa still

in her bedroom, Liesel sat on the other side of the fireplace from Max. Behind

them, Mama loudly slept. She gave the snorer on the train a good run for her

money.

in her bedroom, Liesel sat on the other side of the fireplace from Max. Behind

them, Mama loudly slept. She gave the snorer on the train a good run for her

money.

The fire was

nothing now but a funeral of smoke, dead and dying, simultaneously. On this

particular morning, there were also voices.

nothing now but a funeral of smoke, dead and dying, simultaneously. On this

particular morning, there were also voices.

THE

SWAPPING OF NIGHTMARES

SWAPPING OF NIGHTMARES

The girl:

“Tell me. What do you see

“Tell me. What do you see

when you dream like that?”

The Few:

“. . . I see myself turning

“. . . I see myself turning

around, and waving goodbye.”

The girl:

“I also have nightmares.”

“I also have nightmares.”

The Few:

“What do you see?”

“What do you see?”

The girl:

“A train, and my dead brother.”

“A train, and my dead brother.”

The Few:

“Your brother?”

“Your brother?”

The girl:

“He died when I moved

“He died when I moved

here, on the way.”

The girl and the Few, together:

“

Fa

—yes.”

“

Fa

—yes.”

It would be nice

to say that after this small breakthrough, neither Liesel nor Max dreamed their

bad visions again. It would be nice but untrue. The nightmares arrived like

they always did, much like the best player in the opposition when you’ve heard

rumors that he might be injured or sick—but there he is, warming up with the

rest of them, ready to take the field. Or like a timetabled train, arriving at

a nightly platform, pulling the memories behind it on a rope. A lot of

dragging. A lot of awkward bounces.

to say that after this small breakthrough, neither Liesel nor Max dreamed their

bad visions again. It would be nice but untrue. The nightmares arrived like

they always did, much like the best player in the opposition when you’ve heard

rumors that he might be injured or sick—but there he is, warming up with the

rest of them, ready to take the field. Or like a timetabled train, arriving at

a nightly platform, pulling the memories behind it on a rope. A lot of

dragging. A lot of awkward bounces.

The only thing

that changed was that Liesel told her papa that she should be old enough now to

cope on her own with the dreams. For a moment, he looked a little hurt, but as

always with Papa, he gave the right thing to say his best shot.

that changed was that Liesel told her papa that she should be old enough now to

cope on her own with the dreams. For a moment, he looked a little hurt, but as

always with Papa, he gave the right thing to say his best shot.

“Well, thank

God.” He halfway grinned. “At least now I can get some proper sleep. That chair

was killing me.” He put his arm around the girl and they walked to the kitchen.

God.” He halfway grinned. “At least now I can get some proper sleep. That chair

was killing me.” He put his arm around the girl and they walked to the kitchen.

As time

progressed, a clear distinction developed between two very different worlds—the

world inside 33 Himmel Street, and the one that resided and turned outside it.

The trick was to keep them apart.

progressed, a clear distinction developed between two very different worlds—the

world inside 33 Himmel Street, and the one that resided and turned outside it.

The trick was to keep them apart.

In the outside

world, Liesel was learning to find some more of its uses. One afternoon, when

she was walking home with an empty washing bag, she noticed a newspaper poking

out of a garbage can. The weekly edition of the

Molching Express.

She

lifted it out and took it home, presenting it to Max. “I thought,” she told

him, “you might like to do the crossword to pass the time.”

world, Liesel was learning to find some more of its uses. One afternoon, when

she was walking home with an empty washing bag, she noticed a newspaper poking

out of a garbage can. The weekly edition of the

Molching Express.

She

lifted it out and took it home, presenting it to Max. “I thought,” she told

him, “you might like to do the crossword to pass the time.”

Max appreciated

the gesture, and to justify her bringing it home, he read the paper from cover

to cover and showed her the puzzle a few hours later, completed but for one

word.

the gesture, and to justify her bringing it home, he read the paper from cover

to cover and showed her the puzzle a few hours later, completed but for one

word.

“Damn that

seventeen down,” he said.

seventeen down,” he said.

In February

1941, for her twelfth birthday, Liesel received another used book, and she was

grateful. It was called

The Mud Men

and was about a very strange father

and son. She hugged her mama and papa, while Max stood uncomfortably in the

corner.

1941, for her twelfth birthday, Liesel received another used book, and she was

grateful. It was called

The Mud Men

and was about a very strange father

and son. She hugged her mama and papa, while Max stood uncomfortably in the

corner.

“Alles Gute zum

Geburtstag.”

He

smiled weakly. “All the best for your birthday.” His hands were in his pockets.

“I didn’t know, or else I could have given you something.” A blatant lie—he had

nothing to give, except maybe

Mein Kampf,

and there was no way he’d give

such propaganda to a young German girl. That would be like the lamb handing a

knife to the butcher.

Geburtstag.”

He

smiled weakly. “All the best for your birthday.” His hands were in his pockets.

“I didn’t know, or else I could have given you something.” A blatant lie—he had

nothing to give, except maybe

Mein Kampf,

and there was no way he’d give

such propaganda to a young German girl. That would be like the lamb handing a

knife to the butcher.

There was an

uncomfortable silence.

uncomfortable silence.

She had embraced

Mama and Papa.

Mama and Papa.

Max looked so

alone.

alone.

Liesel

swallowed.

swallowed.

And she walked

over and hugged him for the first time. “Thanks, Max.”

over and hugged him for the first time. “Thanks, Max.”

At first, he

merely stood there, but as she held on to him, gradually his hands rose up and

gently pressed into her shoulder blades.

merely stood there, but as she held on to him, gradually his hands rose up and

gently pressed into her shoulder blades.

Only later would

she find out about the helpless expression on Max Vandenburg’s face. She would

also discover that he resolved at that moment to give her something back. I

often imagine him lying awake all that night, pondering what he could possibly

offer.

she find out about the helpless expression on Max Vandenburg’s face. She would

also discover that he resolved at that moment to give her something back. I

often imagine him lying awake all that night, pondering what he could possibly

offer.

As it turned

out, the gift was delivered on paper, just over a week later.

out, the gift was delivered on paper, just over a week later.

He would bring

it to her in the early hours of morning, before retreating down the concrete

steps to what he now liked to call home.

it to her in the early hours of morning, before retreating down the concrete

steps to what he now liked to call home.

PAGES FROM THE BASEMENT

For a week,

Liesel was kept from the basement at all cost. It was Mama and Papa who made

sure to take down Max’s food.

Liesel was kept from the basement at all cost. It was Mama and Papa who made

sure to take down Max’s food.

“No,

Saumensch,

”

Mama told her each time she volunteered. There was always a new excuse. “How

about you do something useful in

here

for a change, like finish the

ironing? You think carrying it around town is so special? Try ironing it!” You

can do all manner of underhanded nice things when you have a caustic

reputation. It worked.

Saumensch,

”

Mama told her each time she volunteered. There was always a new excuse. “How

about you do something useful in

here

for a change, like finish the

ironing? You think carrying it around town is so special? Try ironing it!” You

can do all manner of underhanded nice things when you have a caustic

reputation. It worked.

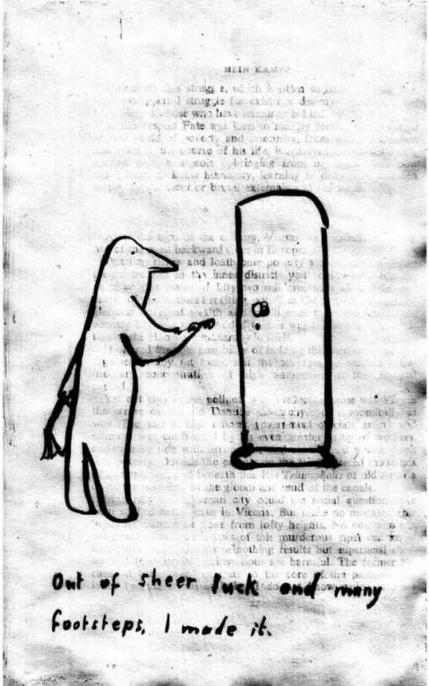

During that

week, Max had cut out a collection of pages from

Mein Kampf

and painted

over them in white. He then hung them up with pegs on some string, from one end

of the basement to the other. When they were all dry, the hard part began. He

was educated well enough to get by, but he was certainly no writer, and no

artist. Despite this, he formulated the words in his head till he could recount

them without error. Only then, on the paper that had bubbled and humped under

the stress of drying paint, did he begin to write the story. It was done with a

small black paintbrush.

week, Max had cut out a collection of pages from

Mein Kampf

and painted

over them in white. He then hung them up with pegs on some string, from one end

of the basement to the other. When they were all dry, the hard part began. He

was educated well enough to get by, but he was certainly no writer, and no

artist. Despite this, he formulated the words in his head till he could recount

them without error. Only then, on the paper that had bubbled and humped under

the stress of drying paint, did he begin to write the story. It was done with a

small black paintbrush.

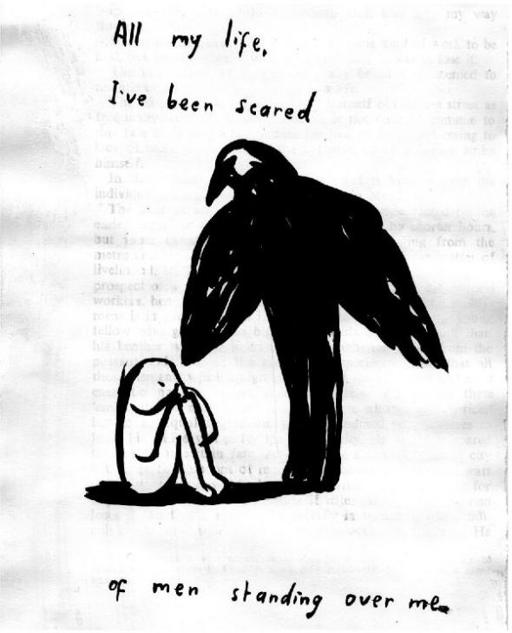

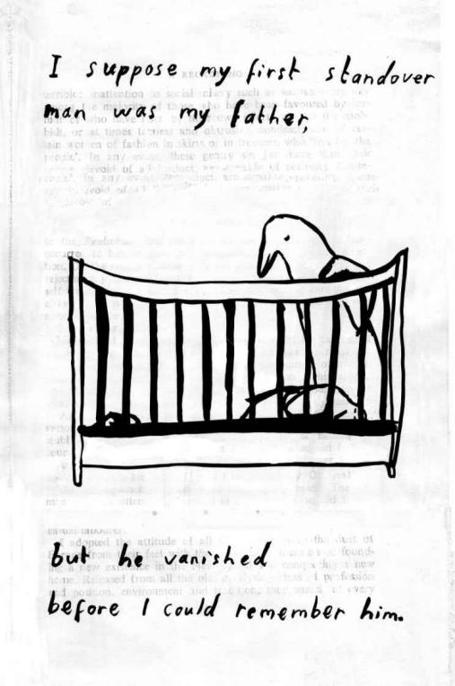

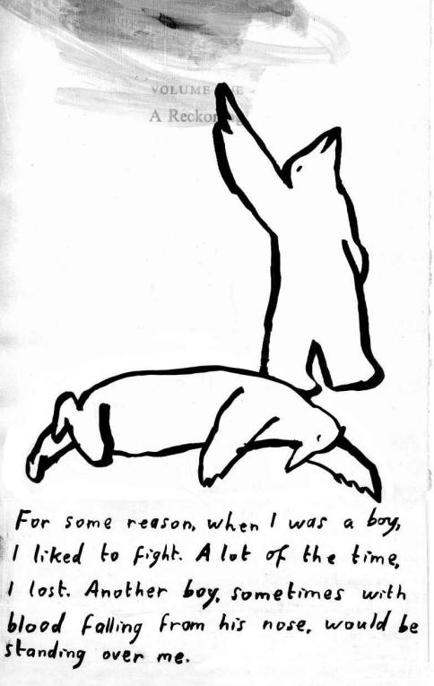

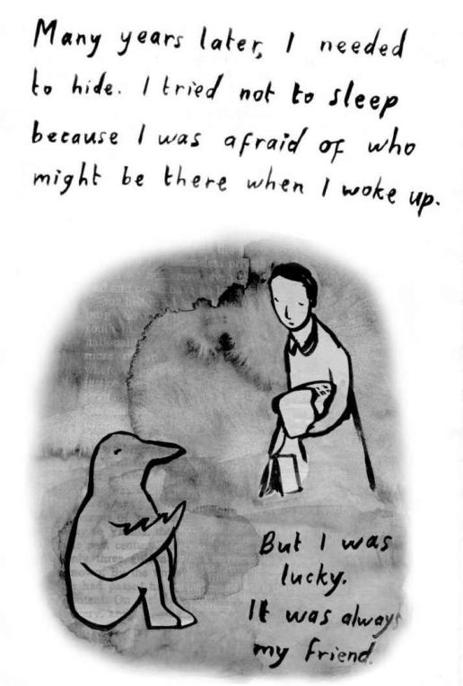

The Standover

Man.

Man.

He calculated

that he needed thirteen pages, so he painted forty, expecting at least twice as

many slipups as successes. There were practice versions on the pages of the

Molching

Express,

improving his basic, clumsy artwork to a level he could accept. As

he worked, he heard the whispered words of a girl. “His hair,” she told him,

“is like feathers.”

that he needed thirteen pages, so he painted forty, expecting at least twice as

many slipups as successes. There were practice versions on the pages of the

Molching

Express,

improving his basic, clumsy artwork to a level he could accept. As

he worked, he heard the whispered words of a girl. “His hair,” she told him,

“is like feathers.”

When he was

finished, he used a knife to pierce the pages and tie them with string. The

result was a thirteen-page booklet that went like this:

finished, he used a knife to pierce the pages and tie them with string. The

result was a thirteen-page booklet that went like this:

Other books

Cyrosphere 8: Lives Uneasily Affected by Deandre Dean

Forbidden Fires by Madeline Baker

Yaccub's Curse by Wrath James White

Hunter's Season: Elder Races, Book 4 by Thea Harrison

An Excellent Wife by Lamb, Charlotte

Light Errant by Chaz Brenchley

Shane's Bride (Mail Order Brides of Texas #3) by Kathleen Ball

Wild Horses by D'Ann Lindun

The Cambridge Curry Club by Saumya Balsari

Junie B. Jones and Some Sneaky Peeky Spying by Barbara Park