The Book Thief (30 page)

Authors: Markus Zusak

Tags: #Fiction, #death, #Storytelling, #General, #Europe, #Historical, #Juvenile Fiction, #Holocaust, #Children: Young Adult (Gr. 7-9), #Religious, #Books and reading, #Historical - Holocaust, #Social Issues, #Jewish, #Books & Libraries, #Military & Wars, #Books and reading/ Fiction, #Storytelling/ Fiction, #Historical Fiction (Young Adult), #Death & Dying, #Death/ Fiction, #Juvenile Fiction / Historical / Holocaust

“Last year,” she

listed, “I stole at least three hundred apples and dozens of potatoes. I have

little trouble with barbed wire fences and I can keep up with anyone here.”

listed, “I stole at least three hundred apples and dozens of potatoes. I have

little trouble with barbed wire fences and I can keep up with anyone here.”

“Is that right?”

“Yes.” She did

not shrink or step away. “All I ask is a small part of anything we take. A

dozen apples here or there. A few leftovers for me and my friend.”

not shrink or step away. “All I ask is a small part of anything we take. A

dozen apples here or there. A few leftovers for me and my friend.”

“Well, I suppose

that can be arranged.” Viktor lit a cigarette and raised it to his mouth. He

made a concerted effort to blow his next mouthful in Liesel’s face.

that can be arranged.” Viktor lit a cigarette and raised it to his mouth. He

made a concerted effort to blow his next mouthful in Liesel’s face.

Liesel did not

cough.

cough.

It was the same

group as the previous year, the only exception being the leader. Liesel

wondered why none of the other boys had assumed the helm, but looking from face

to face, she realized that none of them had it. They had no qualms about

stealing, but they needed to be told. They

liked

to be told, and Viktor

Chemmel liked to be the teller. It was a nice microcosm.

group as the previous year, the only exception being the leader. Liesel

wondered why none of the other boys had assumed the helm, but looking from face

to face, she realized that none of them had it. They had no qualms about

stealing, but they needed to be told. They

liked

to be told, and Viktor

Chemmel liked to be the teller. It was a nice microcosm.

For a moment,

Liesel longed for the reappearance of Arthur Berg. Or would he, too, have

fallen under the leadership of Chemmel? It didn’t matter. Liesel only knew that

Arthur Berg did not have a tyrannical bone in his body, whereas the new leader

had hundreds of them. Last year, she knew that if she was stuck in a tree,

Arthur would come back for her, despite claiming otherwise. This year, by

comparison, she was instantly aware that Viktor Chemmel wouldn’t even bother to

look back.

Liesel longed for the reappearance of Arthur Berg. Or would he, too, have

fallen under the leadership of Chemmel? It didn’t matter. Liesel only knew that

Arthur Berg did not have a tyrannical bone in his body, whereas the new leader

had hundreds of them. Last year, she knew that if she was stuck in a tree,

Arthur would come back for her, despite claiming otherwise. This year, by

comparison, she was instantly aware that Viktor Chemmel wouldn’t even bother to

look back.

He stood,

regarding the lanky boy and the malnourished-looking girl. “So you want to

steal with me?”

regarding the lanky boy and the malnourished-looking girl. “So you want to

steal with me?”

What did they

have to lose? They nodded.

have to lose? They nodded.

He stepped

closer and grabbed Rudy’s hair. “I want to hear it.”

closer and grabbed Rudy’s hair. “I want to hear it.”

“Definitely,”

Rudy said, before being shoved back, fringe first.

Rudy said, before being shoved back, fringe first.

“And you?”

“Of course.”

Liesel was quick enough to avoid the same treatment.

Liesel was quick enough to avoid the same treatment.

Viktor smiled.

He squashed his cigarette, breathed deeply in, and scratched his chest. “My

gentlemen, my whore, it looks like it’s time to go shopping.”

He squashed his cigarette, breathed deeply in, and scratched his chest. “My

gentlemen, my whore, it looks like it’s time to go shopping.”

As the group

walked off, Liesel and Rudy were at the back, as they’d always been in the

past.

walked off, Liesel and Rudy were at the back, as they’d always been in the

past.

“Do you like

him?” Rudy whispered.

him?” Rudy whispered.

“Do you?”

Rudy paused a

moment. “I think he’s a complete bastard.”

moment. “I think he’s a complete bastard.”

“Me too.”

The group was

getting away from them.

getting away from them.

“Come on,” Rudy

said, “we’ve fallen behind.”

said, “we’ve fallen behind.”

After a few

miles, they reached the first farm. What greeted them was a shock. The trees

they’d imagined to be swollen with fruit were frail and injured-looking, with

only a small array of apples hanging miserly from each branch. The next farm

was the same. Maybe it was a bad season, or their timing wasn’t quite right.

miles, they reached the first farm. What greeted them was a shock. The trees

they’d imagined to be swollen with fruit were frail and injured-looking, with

only a small array of apples hanging miserly from each branch. The next farm

was the same. Maybe it was a bad season, or their timing wasn’t quite right.

By the end of

the afternoon, when the spoils were handed out, Liesel and Rudy were given one

diminutive apple between them. In fairness, the takings were incredibly poor,

but Viktor Chemmel also ran a tighter ship.

the afternoon, when the spoils were handed out, Liesel and Rudy were given one

diminutive apple between them. In fairness, the takings were incredibly poor,

but Viktor Chemmel also ran a tighter ship.

“What do you

call this?” Rudy asked, the apple resting in his palm.

call this?” Rudy asked, the apple resting in his palm.

Viktor didn’t

even turn around. “What does it look like?” The words were dropped over his

shoulder.

even turn around. “What does it look like?” The words were dropped over his

shoulder.

“One lousy

apple?”

apple?”

“Here.” A

half-eaten one was also tossed their way, landing chewed-side-down in the dirt.

“You can have that one, too.”

half-eaten one was also tossed their way, landing chewed-side-down in the dirt.

“You can have that one, too.”

Rudy was

incensed. “To hell with this. We didn’t walk ten miles for one and a half

scrawny apples, did we, Liesel?”

incensed. “To hell with this. We didn’t walk ten miles for one and a half

scrawny apples, did we, Liesel?”

Liesel did not

answer.

answer.

She did not have

time, for Viktor Chemmel was on top of Rudy before she could utter a word. His

knees had pinned Rudy’s arms and his hands were around his throat. The apples

were scooped up by none other than Andy Schmeikl, at Viktor’s request.

time, for Viktor Chemmel was on top of Rudy before she could utter a word. His

knees had pinned Rudy’s arms and his hands were around his throat. The apples

were scooped up by none other than Andy Schmeikl, at Viktor’s request.

“You’re hurting

him,” Liesel said.

him,” Liesel said.

“Am I?” Viktor

was smiling again. She hated that smile.

was smiling again. She hated that smile.

“He’s

not

hurting

me.” Rudy’s words were rushed together and his face was red with strain. His

nose began to bleed.

not

hurting

me.” Rudy’s words were rushed together and his face was red with strain. His

nose began to bleed.

After an

extended moment or two of increased pressure, Viktor let Rudy go and climbed

off him, taking a few careless steps. He said, “Get up, boy,” and Rudy,

choosing wisely, did as he was told.

extended moment or two of increased pressure, Viktor let Rudy go and climbed

off him, taking a few careless steps. He said, “Get up, boy,” and Rudy,

choosing wisely, did as he was told.

Viktor came

casually closer again and faced him. He gave him a gentle rub on the arm. A

whisper. “Unless you want me to turn that blood into a fountain, I suggest you

go away, little boy.” He looked at Liesel. “And take the little slut with you.”

casually closer again and faced him. He gave him a gentle rub on the arm. A

whisper. “Unless you want me to turn that blood into a fountain, I suggest you

go away, little boy.” He looked at Liesel. “And take the little slut with you.”

No one moved.

“Well, what are

you waiting for?”

you waiting for?”

Liesel took

Rudy’s hand and they left, but not before Rudy turned one last time and spat

some blood and saliva at Viktor Chemmel’s feet. It evoked one final remark.

Rudy’s hand and they left, but not before Rudy turned one last time and spat

some blood and saliva at Viktor Chemmel’s feet. It evoked one final remark.

A

SMALL THREAT FROM

SMALL THREAT FROM

VIKTOR CHEMMEL TO RUDY STEINER

“You’ll pay for that at a later date, my friend.”

Say what you

will about Viktor Chemmel, but he certainly had patience and a good memory. It

took him approximately five months to turn his statement into a true one.

will about Viktor Chemmel, but he certainly had patience and a good memory. It

took him approximately five months to turn his statement into a true one.

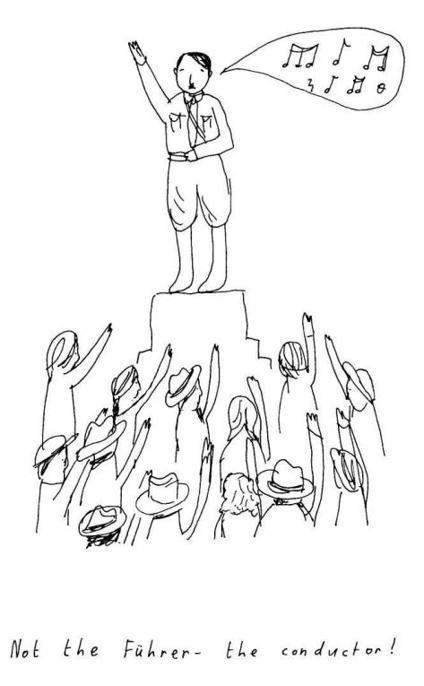

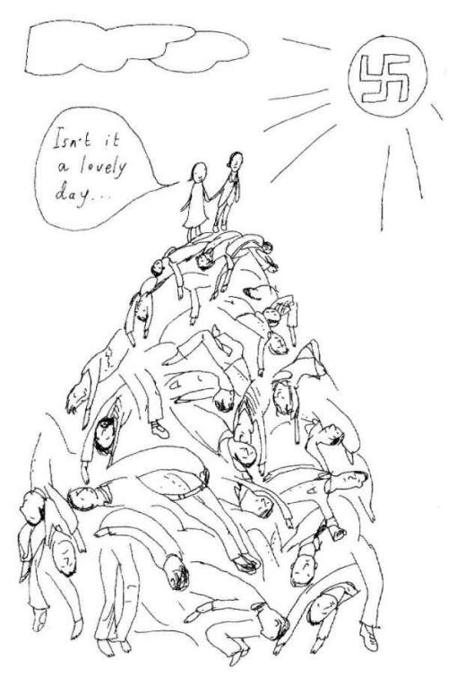

SKETCHES

If the summer of

1941 was walling up around the likes of Rudy and Liesel, it was writing and

painting itself into the life of Max Vandenburg. In his loneliest moments in

the basement, the words started piling up around him. The visions began to pour

and fall and occasionally limp from out of his hands.

1941 was walling up around the likes of Rudy and Liesel, it was writing and

painting itself into the life of Max Vandenburg. In his loneliest moments in

the basement, the words started piling up around him. The visions began to pour

and fall and occasionally limp from out of his hands.

He had what he

called just a small ration of tools:

called just a small ration of tools:

A painted book.

A handful of

pencils.

pencils.

A mindful of

thoughts.

thoughts.

Like a simple

puzzle, he put them together.

puzzle, he put them together.

Originally, Max

had intended to write his own story.

had intended to write his own story.

The idea was to

write about everything that had happened to him—all that had led him to a

Himmel Street basement—but it was not what came out. Max’s exile produced

something else entirely. It was a collection of random thoughts and he chose to

embrace them. They felt

true.

They were more real than the letters he

wrote to his family and to his friend Walter Kugler, knowing very well that he

could never send them. The desecrated pages of

Mein Kampf

were becoming

a series of sketches, page after page, which to him summed up the events that

had swapped his former life for another. Some took minutes. Others hours. He

resolved that when the book was finished, he’d give it to Liesel, when she was

old enough, and hopefully, when all this nonsense was over.

write about everything that had happened to him—all that had led him to a

Himmel Street basement—but it was not what came out. Max’s exile produced

something else entirely. It was a collection of random thoughts and he chose to

embrace them. They felt

true.

They were more real than the letters he

wrote to his family and to his friend Walter Kugler, knowing very well that he

could never send them. The desecrated pages of

Mein Kampf

were becoming

a series of sketches, page after page, which to him summed up the events that

had swapped his former life for another. Some took minutes. Others hours. He

resolved that when the book was finished, he’d give it to Liesel, when she was

old enough, and hopefully, when all this nonsense was over.

From the moment

he tested the pencils on the first painted page, he kept the book close at all

times. Often, it was next to him or still in his fingers as he slept.

he tested the pencils on the first painted page, he kept the book close at all

times. Often, it was next to him or still in his fingers as he slept.

One afternoon,

after his push-ups and sit-ups, he fell asleep against the basement wall. When

Liesel came down, she found the book sitting next to him, slanted against his

thigh, and curiosity got the better of her. She leaned over and picked it up,

waiting for him to stir. He didn’t. Max was sitting with his head and shoulder

blades against the wall. She could barely make out the sound of his breath,

coasting in and out of him, as she opened the book and glimpsed a few random

pages. . . .

after his push-ups and sit-ups, he fell asleep against the basement wall. When

Liesel came down, she found the book sitting next to him, slanted against his

thigh, and curiosity got the better of her. She leaned over and picked it up,

waiting for him to stir. He didn’t. Max was sitting with his head and shoulder

blades against the wall. She could barely make out the sound of his breath,

coasting in and out of him, as she opened the book and glimpsed a few random

pages. . . .

Frightened by

what she saw, Liesel placed the book back down, exactly as she found it,

against Max’s leg.

what she saw, Liesel placed the book back down, exactly as she found it,

against Max’s leg.

A voice startled

her.

her.

“Danke schön,”

it said, and

when she looked across, following the trail of sound to its owner, a small sign

of satisfaction was present on his Jewish lips.

it said, and

when she looked across, following the trail of sound to its owner, a small sign

of satisfaction was present on his Jewish lips.

“Holy Christ,”

Liesel gasped. “You scared me, Max.”

Liesel gasped. “You scared me, Max.”

He returned to

his sleep, and behind her, the girl dragged the same thought up the steps.

his sleep, and behind her, the girl dragged the same thought up the steps.

You scared me,

Max.

Max.

THE WHISTLER AND THE SHOES

The same pattern

continued through the end of summer and well into autumn. Rudy did his best to

survive the Hitler Youth. Max did his push-ups and made his sketches. Liesel

found newspapers and wrote her words on the basement wall.

continued through the end of summer and well into autumn. Rudy did his best to

survive the Hitler Youth. Max did his push-ups and made his sketches. Liesel

found newspapers and wrote her words on the basement wall.

It’s also worthy

of mention that every pattern has at least one small bias, and one day it will

tip itself over, or fall from one page to another. In this case, the dominant

factor was Rudy. Or at least, Rudy and a freshly fertilized sports field.

of mention that every pattern has at least one small bias, and one day it will

tip itself over, or fall from one page to another. In this case, the dominant

factor was Rudy. Or at least, Rudy and a freshly fertilized sports field.

Late in October,

all appeared to be usual. A filthy boy was walking down Himmel Street. Within a

few minutes, his family would expect his arrival, and he would lie that

everyone in his Hitler Youth division was given extra drills in the field. His

parents would even expect some laughter. They didn’t get it.

all appeared to be usual. A filthy boy was walking down Himmel Street. Within a

few minutes, his family would expect his arrival, and he would lie that

everyone in his Hitler Youth division was given extra drills in the field. His

parents would even expect some laughter. They didn’t get it.

Today Rudy was

all out of laughter and lies.

all out of laughter and lies.

On this

particular Wednesday, when Liesel looked more closely, she could see that Rudy

Steiner was shirtless. And he was furious.

particular Wednesday, when Liesel looked more closely, she could see that Rudy

Steiner was shirtless. And he was furious.

“What happened?”

she asked as he trudged past.

she asked as he trudged past.

He reversed back

and held out the shirt. “Smell it,” he said.

and held out the shirt. “Smell it,” he said.

“What?”

“Are you deaf? I

said smell it.”

said smell it.”

Reluctantly,

Liesel leaned in and caught a ghastly whiff of the brown garment. “Jesus, Mary,

and Joseph! Is that—?”

Liesel leaned in and caught a ghastly whiff of the brown garment. “Jesus, Mary,

and Joseph! Is that—?”

The boy nodded.

“It’s on my chin, too. My chin! I’m lucky I didn’t swallow it!”

“It’s on my chin, too. My chin! I’m lucky I didn’t swallow it!”

“Jesus, Mary,

and Joseph.”

and Joseph.”

“The field at

Hitler Youth just got fertilized.” He gave his shirt another halfhearted,

disgusted appraisal. “It’s cow manure, I think.”

Hitler Youth just got fertilized.” He gave his shirt another halfhearted,

disgusted appraisal. “It’s cow manure, I think.”

“Did

what’s-his-name—Deutscher—know it was there?”

what’s-his-name—Deutscher—know it was there?”

“He says he

didn’t. But he was grinning.”

didn’t. But he was grinning.”

“Jesus, Mary,

and—”

and—”

“Could you stop

saying that?!”

saying that?!”

What Rudy needed

at this point in time was a victory. He had lost in his dealings with Viktor

Chemmel. He’d endured problem after problem at the Hitler Youth. All he wanted

was a small scrap of triumph, and he was determined to get it.

at this point in time was a victory. He had lost in his dealings with Viktor

Chemmel. He’d endured problem after problem at the Hitler Youth. All he wanted

was a small scrap of triumph, and he was determined to get it.

He continued

home, but when he reached the concrete step, he changed his mind and came

slowly, purposefully back to the girl.

home, but when he reached the concrete step, he changed his mind and came

slowly, purposefully back to the girl.

Careful and

quiet, he spoke. “You know what would cheer me up?”

quiet, he spoke. “You know what would cheer me up?”

Liesel cringed.

“If you think I’m going to—in that state . . .”

“If you think I’m going to—in that state . . .”

He seemed

disappointed in her. “No, not that.” He sighed and stepped closer. “Something

else.” After a moment’s thought, he raised his head, just a touch. “Look at me.

I’m filthy. I stink like cow shit, or dog shit, whatever your opinion, and as

usual, I’m absolutely starving.” He paused. “I need a win, Liesel. Honestly.”

disappointed in her. “No, not that.” He sighed and stepped closer. “Something

else.” After a moment’s thought, he raised his head, just a touch. “Look at me.

I’m filthy. I stink like cow shit, or dog shit, whatever your opinion, and as

usual, I’m absolutely starving.” He paused. “I need a win, Liesel. Honestly.”

Liesel knew.

She’d have gone

closer but for the smell of him.

closer but for the smell of him.

Stealing.

They had to

steal something.

steal something.

No.

They had to

steal something

back.

It didn’t matter what. It needed only to be soon.

steal something

back.

It didn’t matter what. It needed only to be soon.

“Just you and me

this time,” Rudy suggested. “No Chemmels, no Schmeikls. Just you and me.”

this time,” Rudy suggested. “No Chemmels, no Schmeikls. Just you and me.”

The girl couldn’t

help it.

help it.

Her hands

itched, her pulse split, and her mouth smiled all at the same time. “Sounds

good.”

itched, her pulse split, and her mouth smiled all at the same time. “Sounds

good.”

“It’s agreed,

then,” and although he tried not to, Rudy could not hide the fertilized grin

that grew on his face. “Tomorrow?”

then,” and although he tried not to, Rudy could not hide the fertilized grin

that grew on his face. “Tomorrow?”

Liesel nodded.

“Tomorrow.”

“Tomorrow.”

Their plan was

perfect but for one thing:

perfect but for one thing:

They had no idea

where to start.

where to start.

Fruit was out.

Rudy snubbed his nose at onions and potatoes, and they drew the line at another

attempt on Otto Sturm and his bikeful of farm produce. Once was immoral. Twice

was complete bastardry.

Rudy snubbed his nose at onions and potatoes, and they drew the line at another

attempt on Otto Sturm and his bikeful of farm produce. Once was immoral. Twice

was complete bastardry.

“So where the

hell do we go?” Rudy asked.

hell do we go?” Rudy asked.

“How should I

know? This was your idea, wasn’t it?”

know? This was your idea, wasn’t it?”

“That doesn’t

mean you shouldn’t think a little, too. I can’t think of everything.”

mean you shouldn’t think a little, too. I can’t think of everything.”

“You can barely

think of

anything

. . . .”

think of

anything

. . . .”

They argued on as

they walked through town. On the outskirts, they witnessed the first of the

farms and the trees standing like emaciated statues. The branches were gray and

when they looked up at them, there was nothing but ragged limbs and empty sky.

they walked through town. On the outskirts, they witnessed the first of the

farms and the trees standing like emaciated statues. The branches were gray and

when they looked up at them, there was nothing but ragged limbs and empty sky.

Other books

Obeying the Bear: BBW Paranormal Shapeshifter Romance (The Callaghan Clan Book 1) by Meredith Clarke, Ashlee Sinn

The Forbidden Touch of Sanguardo by Julia James

Dangerous Temptation by Anne Mather

Will of Man - Part Three by William Scanlan

Consider by Kristy Acevedo

The Marine Next Door by Julie Miller

Color Blind by Colby Marshall

The Seduction Vow by Bonnie Dee

Forever My Love: A Contenporary Romance (The Armstrongs Book 2) by Gray, Jessica

Christmas Miracles of a Recently Fallen Spruce by Brandon Witt