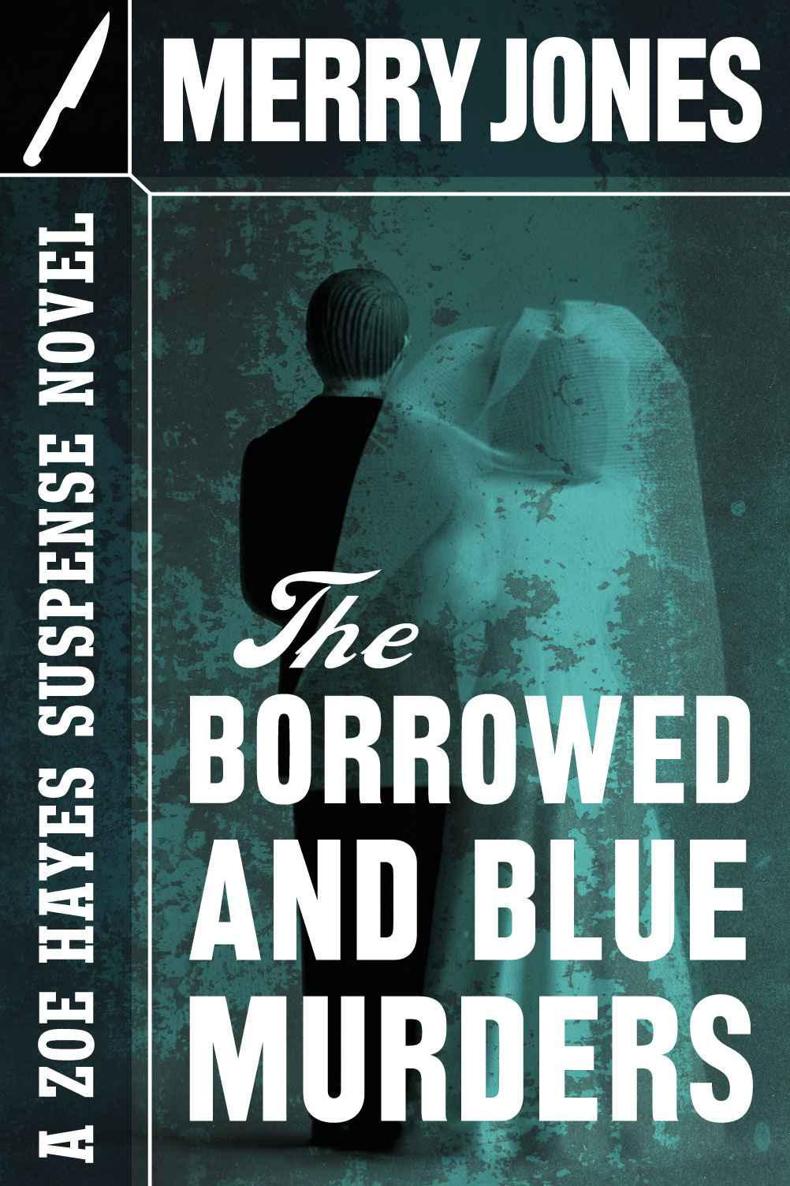

The Borrowed and Blue Murders (The Zoe Hayes Mysteries)

Read The Borrowed and Blue Murders (The Zoe Hayes Mysteries) Online

Authors: Merry Jones

OOKS BY

M

ERRY

J

ONES

Mystery

:

Humor

:

AMERICA’S DUMBEST DATES

IF SHE WEREN’T MY BEST FRIEND, I’D KILL HER

PLEASE DON’T KISS ME AT THE BUS STOP

I LOVE HER, BUT… (as Robin Jones)

:

BIRTHMOTHERS: WOMEN WHO HAVE RELINQUISHED BABIES FOR ADOPTION TELL THEIR STORIES

STEPMOTHERS: KEEPING IT TOGETHER WITH YOUR HUSBAND AND HIS KIDS

HE

B

ORROWED AND

B

LUE

M

URDERS

M

ERRY

J

ONES

A Merry Jones Reprint

In memory of my mom, E. Judith Block

CKNOWLEDGMENTS

I

N WRITING THIS BOOK

, I’ve received mega doses of encouragement and support from lots of people. Heartfelt thanks go out to more people than I can name on this page, but here are a few:

Rob and Amy Siders at 52 Novels for helping me revive my out-of-print mysteries;

Stewart Williams for designing the series’ covers;

Cheryl Perez for working on the print on demand versions;

The Philadelphia Liars Club (Jonathan Maberry, Jon McGoran, Greg Frost, Ed Pettit, Dennis Tafoya, Solomon Jones, Marie Lamba, Kelly Simmons, Leslie E. Banks, Don Lafferty, Keith Strunk, Keith DeCandido) for their endless encouragement, shared insights and valued friendships,

My precious daughters and husband for their enduring love and support.

NE

P

ERCHED LIKE A FLAMINGO

on one leg, I tried to balance the groceries on my thigh without disturbing baby Luke, who was sound asleep in his sling. Somehow, I managed to unlock the front door and juggle my way inside without dropping the lemon meringue pie that was teetering perilously on top of the pretzel packages, and I made it into the kitchen without waking him or losing hold of either bag.

The house still reeked of last night’s beer. Judging by the empties lined up on the kitchen counter, Nick and his brothers had gone through several six-packs. Not that I blamed them, really. It was a family reunion. If not for the baby, I’d undoubtedly have joined in, drinking my share for no reason other than to avoid being what I had been lately: the only sober adult in the house. Instead of beer, I’d sipped decaffeinated mint tea, listening to them recount childhood memories, hoot over private jokes, tease each other without mercy and gradually descend into song, performing off-key renditions of their favorite oldies. It had been a long few nights. Actually, a long three nights. Ever since Tuesday, when Tony and Sam had arrived, our house had been home to a nonstop party.

Even so, the demands of daily life continued. Food needed to be bought, meals to be cooked. Shoving the empties aside with my elbow to make room for the grocery bags, I noticed a puddle on the floor next to the refrigerator. Damn. Somebody had let the puppy out of his crate again. And, as if on cue, he raced over, jumping and yipping, nipping at my ankles with joy at our return.

“Oliver, no, no.” I knelt, cradling the baby’s sling with one hand, shaking a finger at him with the other. “No. Do not piddle in the house.”

Oliver, our almost-five-month-old Pembroke Welsh corgi puppy, still wasn’t housebroken. His training kept getting interrupted; things like my giving birth and Nick having his relatives visit tended to interfere. The result was that Oliver left surprises for us all over the house. If he wasn’t leaving deposits, he was chewing on chair legs or shoes, anything he could wrap his mouth around.

When I released his nose, Oliver stared at me with shiny, eager eyes, oblivious to the scolding. In fact, he was smiling, tongue dangling, panting with eagerness and delight, waiting attentively for who knew what. I had to admit he was cute. How was I supposed to stay angry with a little guy who grinned at me with such complete adoration? Sighing, I tightened the wrap that secured Luke to my body and gave Oliver an affectionate scratch before attending to his puddle.

As I looked for the paper towels, though, it occurred to me that, oops, I shouldn’t have petted him. The teacher at puppy school had warned about reinforcing bad behavior. What if Oliver connected the puddle with the scratch and thought I was actually pleased with him for peeing in the kitchen? Damn. I might be counter-training him. But it was too late to take the scratch back. I’d have to be more careful from now on or we’d have an incorrigible corgi, a sociopath, completely indifferent to the concepts of bad and good. Meantime, I had to clean up his puddle.

Where were the paper towels? I hunted, scanning the sink full of breakfast dishes, the still half-full coffeepot, the stack of miscellaneous coupons and carryout menus, eventually spotting the towels behind the knife rack near the phone, which was blinking, the red light flashing, indicating that we had messages. So, grabbing a wad of crumpled paper towels, I multitasked, putting the phone on speaker, dialing our voice mail number and listening as I squatted to attend to the mess, still trying not to awaken Luke.

But I was too late; Luke’s eyes were already open and alert. Any moment, he’d realize he was hungry; I had to hurry. Quickly, supporting Luke’s head with my free hand, I soaked up the puddle, still hoping to get the groceries put away before I had to feed him.

“You have five messages.” The computerized voice sounded impressed. “First message.”

“Zoe, I’ll be back Monday.” It was Ivy, our babysitter, whose car had been stolen earlier in the week while parked right in front of our house. Normally, Ivy walked to work; she lived only about a mile away. But the one time she’d driven, her car had vanished in broad daylight. Ivy’s voice now reported that she had spent the entire day doing the paperwork for her car insurance and she was ready to come back to work. From her tone, I could tell that she still blamed me for the theft. Somehow, she’d figured that since her car had been parked on my street, it was my fault that it was stolen. I’d been unable to convince her otherwise. Ivy took no responsibility for the loss, even though she knew the neighborhood as well as I did. The crime rate was high in Philadelphia, and it seemed to be higher than average in our neighborhood, Queen Village. The area was in transition, but it was a long way from gentrified. Robberies, muggings, even drive-by shootings were not unheard of. Addicts and drunks frequented the nighttime sidewalks that by day sported upscale perambulators. The street wasn’t a place you’d let children play unsupervised. And it wasn’t a place where you’d leave your parked car unlocked. But according to Ivy, the person who couldn’t remember locking her car, the theft of the vehicle, like her presence on the street, was because of me. Ivy was neither logical nor easy to get along with, but Molly liked her and, despite Ivy’s attitudes, I was desperate. I needed her help. It was already Friday, and there were just eight days until the wedding— Wait. Stop. I had to repeat that fact.

There were just eight days.

Until.

The wedding.

Breathe, I told myself. Just stop and breathe. I closed my eyes and let air rush into my lungs, holding it there for a moment, letting it enter my blood. Then I exhaled slowly. I was on overload, and I had to stop spinning, get organized. But every time I even thought about the w word, my heart did a dizzying break dance and I stopped breathing. Excitement, nerves, joy, panic—I didn’t know what. It didn’t matter, either, because time was passing and there was so much left to do that I had no time for stuff like naming emotions. And, meantime, the lady in the telephone was impatiently repeating that I needed to push 1 to repeat, 2 to save, 3 to delete Ivy’s message.

I stood, pushed 3 and tossed the soggy paper towels into the trash, held a soapy rag under hot water and squatted again, simultaneously telling Oliver to stop jumping on me and cooing to soothe Luke, who’d begun to whimper, awake enough to realize that it was way past time for his every-four-hour meal. I sang him the song about the Puffer Bellies, hoping to distract him for a couple of minutes, long enough for me to at least finish cleaning up the floor. So I washed the tiles, singing, while the puppy chased the soapy rag, chomping and pouncing, trying to grab it, having a wonderful time, and the phone mail voice announced, “Second message.”

This one was from Anna, the special event planner from hell. No, that wasn’t fair. Anna was efficient and detail oriented, persistent and organized; she was everything I needed her to be. It wasn’t her fault that her voice was nasal and sharply birdlike, or that the shape of her glasses reminded me of outstretched wings. And I’d just left her half an hour ago; what could she possibly need to say that she hadn’t already said? It didn’t matter. Anna didn’t need a reason. She called about a dozen times a day, always had one more item to discuss. I stopped singing long enough to listen to her say that she wanted to remind me, even though she’d just reminded me in person, that she needed a final count for the reception dinner. The chef at the Four Seasons required a week’s notice. And Anna needed a decision about whether to go with Amaretto or hazelnut for the cake. I mentally recited the list along with her; she’d repeated it so many times, I had it memorized.

I stood, pushed number 3 to delete, rinsed out the rag, stooped again and, singing, “See the engine driver pull the little handles,” rushed to wipe up the soap bubbles before the puppy could lick them up. “Puff, puff, toot, toot, off we go!” Lulled by either my singing or my repeated standing and stooping, Luke quieted down, burbling softly.

“Third message,” the voice declared, and instantly a frantic soprano voice blurted that she was calling for Zoe Hayes with a message from Haverford Place about Walter Hayes. Oh dear. Walter Hayes was my eighty-three-year-old father. And Haverford Place was the retirement village where he lived. I froze, rag in hand, staring at the phone, dreading the message, praying he was all right. The soprano insisted that she didn’t want to alarm anyone, but she was wondering if, possibly, Ms. Hayes had any idea where her father might be. Because, she didn’t mean to worry his family, but no one had seen Mr. Hayes in a while. Actually, since yesterday. In fact, Walter Hayes appeared to be missing.

Missing? I released a breath, relieved; at least he was alive. As far as we knew, no harm had come to him. All we needed to do was find out where he’d gone. This was not the first time Dad had taken off on his own. He was stubbornly independent, unwilling to account to others for his whereabouts, oblivious to the turmoil he caused when he neglected to sign the ledger book before he went out. Probably he’d gone back to his old neighborhood, stopping by his old house, pulling the “For Sale” sign out of the grass one more time. Or maybe he’d hopped a bus to Atlantic City for some blackjack. Or gone to Delaware Park to play the horses. He was fine. Probably.

But then again, he hadn’t been seen since yesterday. That was a long time, even for my father. I deleted the message and tossed the rag into a bucket under the sink, ready to call Haverford Place. But before I could, the fourth message began, sounding much like the third but less frantic. The soprano, cheerful now, asked Ms. Hayes to disregard her previous call. The search was off; my father had reappeared in prime condition, no need for concern. She didn’t elaborate, offered no details. But that was fine; Dad was safe and accounted for, and that was all I really needed to know. There was no need to hunt for him.

Luke began wriggling, his little mouth rooting around for a nipple. “Fifth message.” It was the last one. I whispered to Luke, asking him to wait while we heard this last message, wincing as soon as I recognized the caller’s voice. Bryce Edmond was the administrator of the Psychiatric Institute where I worked, and he’d been calling all week. In truth, I’d been avoiding him.

“Zoe.” Bryce sounded peeved. “I’ve sent you two dozen e-mails and called you eleven times.” Bryce was nothing if not exact. And while he didn’t want to disturb me during my maternity leave, he needed to speak with me at my earliest convenience.

Damn. Why couldn’t he leave me alone? Obviously, Bryce wanted to talk about work. And I didn’t. Whatever he had to say wasn’t going to be good. The Psychiatric Institute was having financial difficulties; that was old news. My program in art therapy was considered by the administration to be “unessential”; it had already been cut in half. In addition, my three months of maternity leave were just about, if not already, up. So, either Bryce was calling to say that it was time to come back to my job, which I wasn’t ready to do, or he was calling to say that there was no job for me to come back to, which I wasn’t ready to hear. Either way, I figured that if he couldn’t reach me, he couldn’t deliver his news. So, as I had every time he’d called, I pushed number 3, and Bryce was deleted. I told myself not to feel bad about ignoring him. After all, it was just a week until my wedding—oops, there was the w word again—and there went my heart, taking off in its frenzied, dizzying spin, bouncing off my ribs. So Bryce would have to wait. He would have to understand. It wasn’t just the wed—the upcoming event. I also had to care for a new baby, an energetic six-year-old daughter, Molly, an un-housebroken puppy and a houseful of my soon-to-be-in-laws. I simply couldn’t be expected to deal with anything else—certainly not my job. Whatever was on Bryce’s mind would have to wait until after the w—ceremony.