The Boy in the Moon: A Father's Search for His Disabled Son (8 page)

Read The Boy in the Moon: A Father's Search for His Disabled Son Online

Authors: Ian Brown

Tags: #General, #Social Science, #Family & Relationships, #Handicapped, #Parenting, #Personal Memoirs, #Biography & Autobiography

Johanna was better that way: she let other people look after him, wander with him, sit with him. She seemed to feel it was his, her, our due, whereas I literally leapt to take him off their hands. I didn’t want anyone to reject him, so I tried to take rejection out of the picture from the start. He felt like my boy that way. I was not going to let anyone hurt him, he had been hurt enough, and so I would wrap his guilelessness in my constant presence to protect him against everything, even rejection. We were in it together, he and I, it didn’t matter about the others. You could hammer away at me, but you’d never get through to him. Like taking a beating: bury yourself, hunker down, survive until the blows stop raining. It was the least I could do as his father, and at least I did that.

That was why we took him with us, on planes and in the car. In the car was easier: Hayley and Olga and Walker in the back seat, Johanna and I in the front, and everything we needed divided into two loads, the stuff we could pack away in the wayback (that was what we called it) and the detritus we had to have close at hand, for Walker. The at-hand pile comprised the stroller, at least one jumbo pack of thirty-six diapers, a box or two of formula, a small Coleman cooler of medicines, two changes of clothes and bibs and neckerchiefs in a carryall (because he drooled and puked) for the trip itself, a bag of toys and distractions—and that was, as I say, not counting suitcases and his folding playpen/bed. If we were in the car we could take more, of course, adding a second hamper of toys and his plastic “jumper,” a purple and green and yellow plastic rolling contraption with a fabric seat suspended in the middle, in which he could sit and propel himself across the room. He loved that goddamn thing. “Do you like to jump-jump-jump?” Johanna would ask, and he would grin and jump, jump, jump.

We flew with him, too, but to do so was truly hairy, a form of extreme travel we undertook only to see Joanne and Jake, Johanna’s mother and stepfather, in Pennsylvania for Christmas (we set the playpen up between the twin beds in the overheated guest room, the windows open wide even in winter, and tended to him together at nights, trying to shush him so the others wouldn’t wake); to Florida to visit Walt Disney World. (Jake, a devout Catholic, bought indulgences in Walker’s name and prayed to Padre Pio, a local candidate for sainthood.) We never knew if Walker’s ears would react and make him cry the whole way, or if being confined in the plane would drive him (and us) crazy, or if he would instead just sleep or lie in his seat and gaze out the window at the clouds, a smile pasted across his face. We never knew.

In a pinch we tried babysitters. When Olga was away or unavailable, on New Year’s Eve and the big holidays, we hired a sitter from respite agencies that specialized in looking after disabled children. They were first-rate caregivers, mostly unflappable, but until you met them or knew who you were getting, it felt a bit like dropping your kid off with a hired invertebrate. I mean, who is available to babysit on New Year’s Eve? Several were on the eccentric side. A pathologically shy, limping giantess stranger would arrive at the door, and I would pretend that it was the most normal thing in the world to hand over my disabled son (and often my daughter) to a stranger for six hours. “Ah, hello, One-Eye. How are you, nice to see you, come on in, I’m Ian.”

A terrified

eep

from One-Eye would be the only acknowledgement.

“And this … is Walker! Can you say hi, Walker?” Of course I knew he couldn’t say hi, but what was I supposed to say?

Here, you two seem well matched

. Instead I said the only thing I could say: “Let me show you his room.”

There would then follow our standard explanation of the Walker routine. Here is his food, his clothes, his diapers, his changing room, his room, his playroom, his bed. Then the routine itself: he gets this syringe at this time, and 4 cc’s of this at that time, and then two cans of formula every four hours, which you administer like this, attaching this bit here to that bit there and this gizmo into that nozzle—et cetera.

“Hayley knows what to do,” we said, pointing to our lovely four-year-old daughter. It was a little like trying to explain the plumbing of a large complicated house in five minutes before you flew out the door. Because of course we also

wanted

to fly out the door.

But that was when One-Eye would unpack her … bag. Bag? The One-Eyes always carried a carpet bag of contraptions. Puffers and inhalers (their own); bottle of hand cream; snacks (including in one instance an entire loaf of bread; “What’s she going to do?” Joahnna said, after we left. “Have a picnic?”). One woman—she came back several times—found the stairs too much to handle, and we returned after midnight to find her camped out in the living room, Walker alive and well and, always, wide awake. Hayley developed favourites—the woman from the Maritimes who told funny stories about growing up in the country—and others, such as the woman who insisted that Hayley give her all the red sour worms in a bag of candy, and that they be transported to her fingers, one by one. We lived in a world of our own, an underworld of Walker’s making.

six

But let me ask you this: is what we’ve been through so different from what any parent goes through? Even if your child is as normal as a bright day, was our life so far from your own experience? More intensive, perhaps; more extreme more often, yes. But was it really different in kind?

We weren’t disability masochists. I met those people too, the parents of disabled children who seemed to relish their hardship and the opportunity to make everyone else feel guilty and privileged. I disliked them, hated their sense of angry entitlement, their relentless self-pity masquerading as bravery and compassion, their inability to move on, to ask for help. They wanted the world to conform to their circumstances, whereas—as much as I could have put words to it—I simply wanted the rest of the world to admit (a minor request!) that our lives, Walker’s and Hayley’s and my wife’s and mine, weren’t any different from anyone else’s, except in degree of concentration. I realize I was delusional. People often said, “How do you do it? How are you still capable of laughing, when you have a son like that?” And the answer was simple: it was harder than anyone imagined, but more satisfying and rewarding as well. What they didn’t say was: why do you keep him at home with you? Wasn’t there someplace where a child like Walker could be taken care of? Where two parents wouldn’t carry the whole load, and could have a moment or two to work and live and remember who they were and who they could be?

I asked myself those questions too. I knew Walker would have to live in an assisted living environment eventually, but that was surely years away. I approached the subject casually, even at home. “We should put him on the waiting list for a long-term place,” I’d say, off-handedly over breakfast. I tended to think about the problem in bed at night.

“Oh,” Johanna invariably replied, “I’m not ready for that.”

“No, no, not now,” I would say. “Later.”

Just as Walker turned two, he began to grab his ears and bite himself. He didn’t stop for a year and a half. We thought he had a toothache, an earache. He did not.

Self-mutilating

appears for the first time in his medical chart in March 1999, shortly before his third birthday. He quickly graduated to punching himself in the head. He put his body behind the punches, the way a good boxer does. Hayley called it “bonking,” so we did too.

The irony was that he had been making progress, of sorts: finer pincer movements with his fingers, a little eating. (He loved ice cream. If you could get him to swallow it, ice cream made him smile and scowl—from the cold—at the same time.) He could track objects and wave goodbye, and often babbled like a madman.

Then he flipped into blackness.

Was it self-hatred? I wondered about that. We enrolled him in a famous rehabilitation clinic, the Bloorview MacMillan Children’s Centre (now Bloorview Kids Rehab) in north Toronto, where he was seen by a behavioural therapist. Everywhere else when people saw his bruises they wondered what we were doing to our child.

Cannot communicate

, Dr. Saunders noted.

Sometimes Walker was in agony as he smacked himself and screamed with pain. At other times he seemed to do it more expressively, as a way to clear his head, or to let us know he would be saying something if he could talk. Sometimes—and this was unbearably sad—he laughed immediately afterwards. He couldn’t tell us anything, and we had to imagine everything. More specialists crowded into our lives. Walker was diagnosed as functionally autistic—not clinically autistic, but he behaves as if he is—as well as having CFC. Dr. Saunders tried Prozac, Celexa, risperidone (an antipsychotic designed for schizophrenia, it has been known to allay obsessive-compulsive behaviour in children). Nothing worked. Once, in Pennsylvania, he bit his hand to the bone and, after an hour of surgery to repair the damage, spent a night in hospital. (The bill was $14,000.)

Dr. Saunders’ notes began to track longer and longer stretches of horror.

“Bonking” ears × 2–3 days

. I remember that morning, especially the grief-stricken look on Walker’s face as he bashed himself. He looked straight at me. He knew it was bad and wrong, he knew he was hurting himself, he wanted to stop it and couldn’t—why couldn’t I? His normally thin gruel of a wail became frightening and loud. From June 2001 to the spring of 2003, every entry in his medical records mentions his unhappiness, his irritability.

Did he know his window for learning was closing? Was his vision dimming?

72 hours aggressive behaviour. Unhappy crying × 5 days

. Even Dr. Saunders’ handwriting became loose and scrawled, distracted by the chaos of those shrieking visits.

Screaming all day, needs to be held

.

I dreaded the doctor’s waiting room, with its well-dressed mothers and well-behaved children. They were never anything but kind, but walking in with Walker yowling and banging his head, I felt like I’d barged into a church as a naked one-man band with a Roman candle up my ass and singing “Yes! We Have No Bananas.”

Mother tearful

, Dr. Saunders noted on December 29 of that awful year.

Urgent admission for respite

.

I remember that day too. We drove Walker home from the doctor, fed Walker, bathed Walker, soothed Walker, put Walker to bed. I heard his cries subside in stages. Normally Johanna was relieved when he dropped off to sleep, but that night she came downstairs from his bedroom sobbing, her arms wrapped around herself.

“He’s gone away,” she said. “My little boy has gone. Where has he gone?” She was inconsolable.

So perhaps you can understand why, the very next morning, I began to look in earnest for a way out. I didn’t tell Johanna, but I had to find a place for Walker to live, somewhere outside our home. I didn’t realize it would take seven years, that it would be the most painful thing I have ever done and that the pain would never go away.

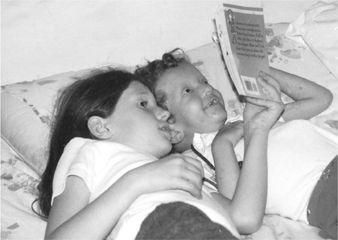

On my desk at work is a picture of Hayley reading to Walker. This was up north, on the quiet island. They are lying side by side on a bed, and Walker is looking up at the book in Hayley’s hands, as if riveted by every word. I don’t know if he understands a syllable. But he can hear her voice, is thrilled to be with her and clearly grasps his smart big sister’s affection. He has become the moment and it has become him, because he has nothing else to be. Walker is an experiment in human life lived in the rare atmosphere of the continuous present. Very few can survive there.

The photograph reminds me of a poem I once read in a magazine, by Mary Jo Salter:

None of us remembers these, the days

When passing strangers adored us at first sight

Just for living, or for rolling down the street

.

Praised all our given names, begged us to smile

.

You, too, in a little while, my darling

,

Will have lost all this

,

asked for a kiss will give one

,

And learn how love dooms one to earn love

Once we can speak of it

.

My boy Walker has no worries there. He never asks, yet is loved by many. But I doubt it feels effortless to him.

“I hear parents of other handicapped kids saying all the time, ‘I wouldn’t change my child,’” Johanna said one night as we were lying in bed, talking as we fell asleep. “They say, ‘I wouldn’t trade him for anything.’ But I would. I would trade Walker, if I could push a button, for the most ordinary kid who got Cs in school. I would trade him in an instant. I wouldn’t trade him for my sake, for our sake. But I would trade for his sake. I think Walker has a very, very hard life.”