The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind (13 page)

Read The Boy Who Harnessed the Wind Online

Authors: William Kamkwamba

“Here at Kachokolo,” he said, “you’ll be given the knowledge to help your country and make it proud.”

We certainly were a fine bunch, all of us eager to learn and squirm

ing with excitement. At that moment, I was certain I was experiencing the greatest day of my life. I couldn’t stop smiling.

“But just like in any institution of learning,” he continued, “this school has rules that must be followed. Every student should be in a proper uniform and be punctual. If not, the punishment shall be swift.”

When assembly was over, I was walking to my classroom with Gilbert, when Mister Phiri tapped me on the shoulder.

“What’s your name?” he said.

“William Trywell Kamkwamba,” I said, unable to hide my nerves.

“Well, William,” he said, “this is not the proper uniform.”

He must’ve noticed my underarms. I wanted to run and hide. But Mister Phiri was pointing down at my feet.

“Sandals aren’t allowed,” he said. “We require students to wear proper footwear at all times, so please go home and change.”

I looked down at my flip-flops, which had certainly seen better days. The rubber connecting the sole had broken on one foot, forcing me to carry in my pocket a crochet needle and bit of rope for emergency repairs. I had no shoes at home. I had to think quickly.

“Mister headmaster, sir,” I said. “I would put on proper footwear, but since I live in Wimbe, I must cross two streams to get here. And because it’s the rainy season, you can imagine how the mud will destroy my good leather shoes. My mother wouldn’t have it.”

He scrunched his eyebrows and considered this. I prayed it would work.

“Okay,” he said. “It’s fine for now, but once the rains are over, I want to see you in

proper

footwear.”

My parents had no money for schoolbooks, either, which cost hundreds of kwacha each. Even in better times, most students couldn’t afford these books and were forced to share. At least in primary school, that meant squeezing your bottoms together on the same chair and hoping the other person didn’t read faster than you did. But luckily for me, Gilbert had managed to buy his own books and said I could look on, which was good because we read at the same level.

At Wimbe Primary, the conditions had been dreadful, with students

having to read and study outside under trees because the classrooms were too full. But even inside the classrooms, the roofs leaked when it rained. The Standard Three classroom was missing an entire wall, and the latrines were not only disgusting but dangerous. Termites had eaten away the floor planks, and one afternoon, one of my classmates named Angela actually fell through. It took hours before anyone heard her screams from the slimy bottom. We never saw her at school again.

I’d been hoping for better conditions at secondary school, but no such luck. Once Gilbert and I arrived in our classroom at Kachokolo, our new teacher, Mister Tembo, told everyone to sit on the floor. It seemed the government had sent no money for desks, and from the looks of things, they hadn’t sent money for repairs, either. A giant hole was in the center of the floor, as if a bomb had exploded.

Right away we began studying history, covering the early civilizations in China, Egypt, and Mesopotamia. We learned about written history and oral history and the early forms of writing. We started algebra in math, which I found incredibly difficult. We also started learning a bit of geometry, and this I absolutely loved. In geometry, we learned about angles and degrees, and I remembered builders in the trading center using such terms.

One afternoon in geography class, Mister Tembo pulled out a world map, and we located the continent of Africa.

“Can anyone find Malawi?” he asked.

“Yah, here it is!”

We ran our fingers over our country, and I marveled at how small a place it was compared to the rest of the earth. To think, my whole life and everything in it had taken place inside this little strip. Looking at it on the map—shaded green with roads zigzagging brown, the lake like a sparkling jewel—you’d never guess that eleven million people lived there, and at that very moment, most of them were slowly starving.

D

ESPITE WHAT

I

’D IMAGINED

earlier, the hunger was just as painful in class as it was in the fields. Actually, it was worse. Sitting there, my stomach

screamed and threatened, twisted in knots, and gave my brain no peace at all. And I soon found it difficult to pay attention. During the first week of school, enthusiasm among my fellow mates had been high, but only two weeks later, the hunger had whittled away at all of us. A gradual silence soon fell over the entire school. At the beginning of term, a dozen hands would shoot up when Mister Tembo asked, “Okay, any questions?” Now no one volunteered. Most just wanted to go home to look for food. I noticed faces getting thinner, then some faces disappearing altogether. And with no lotion or soap at home, people’s skin became gray and dried, as if they were covered in ash. At recess, talk of soccer was replaced by tales of hunger.

“I saw people yesterday eating the maize stalks,” one boy said. “They’re not even sweet yet. I’m sure they became sick.”

“I’ll see you gents later,” said another. “I’m not coming back tomorrow. I don’t think I can manage the walk anymore.”

I suppose none of this really mattered because on the first day of February, W. M. Phiri made this announcement at assembly. “We’re all aware of the problems across the country, which we also face,” he said. “But many of you still haven’t paid your school fees for this term. Starting tomorrow, the grace period is over.”

My stomach tied itself into another knot because I knew my father hadn’t paid my fees. I’d refused to ask him about it these past weeks, knowing what he’d say. The fees were twelve hundred kwacha, and that was collected three times a year. Walking home, I cursed myself for being so optimistic, for allowing myself to become so excited. I wondered why my parents had even allowed me to go to this school in the first place.

“What am I going to do?” I asked Gilbert. “I suppose I’m going home now to face the music.”

“Don’t stress too much,

eh?”

he said. “Just wait and see what happens.”

When I got home, I found my father in the fields.

“At school they’re saying I should bring my fees tomorrow, twelve hundred kwacha,” I said. “So we should pay them. Mister Phiri wasn’t joking around.”

My father looked down at the dirt the same way he’d looked at those sacks of grain in the storage room—as if waiting for it to tell him something. He then gave me the look I’d grown to fear.

“You know our problems here, son,” he said. “We have nothing.”

I was watching his lips move, but in my head, I heard Mister Phiri’s voice, repeating what he’d said as we walked out of school: “No fees. No school.”

“I’m sorry,” said my father. “Next year will be better. Please don’t worry.”

I could see that my father felt terrible, but I was certain it was nothing compared to how sad I felt. The next morning, perhaps just to torture myself, I woke up at the same time, stood at the junction, and waited for Gilbert. I even wore my black trousers and white shirt, though I don’t know why. I wasn’t going anyplace.

Soon Gilbert appeared and walked past. “Come on, William,” he said. “Aren’t you coming to school?”

I wanted to cry but didn’t. “I’m dropping out,” I said. “They don’t have the fees.”

“Oh, sorry, William,” he said. Gilbert looked quite upset, which somehow made me feel better. “Perhaps your parents can find the money.”

“Perhaps,” I said. “I’ll see you later, Gilbert.”

Feeling terrible, I walked over to Geoffrey’s house to share my burden. A few weeks before, Geoffrey had a nice stroke of luck. During a big storm one night, a bolt of lightning had struck a giant blue gum behind his house and caused it to fall. The next morning Geoffrey was outside hacking it apart with his panga. He’d wandered the roads selling clumps of firewood for thirty kwacha apiece, which had allowed his family to eat for a couple of weeks. Between my school and his firewood, I hadn’t seen him much. I was anxious to catch up.

Geoffrey was getting dressed when I walked in, and the very sight of him caused me to stop in place. His clothes looked borrowed, as if they belonged to someone else. His eye sockets were sunken and dark. The whites of his eyes appeared very white, as if he were a ghost or a spirit. My cousin

had once been a big guy, a real bouncer, but now he was down to nothing. It had happened so fast.

“Why aren’t you in school?” he asked. “Didn’t you get selected for Kachokolo?”

“No money,” I said. “Today I dropped.”

“Oh…sorry to hear. Me and you, we’re in the same hopeless situation.”

“For sure.”

He stared down at the floor and shook his head.

“Hopefully God has a plan for us.”

Even after seeing Geoffrey’s condition and leaving his house, I still sulked around feeling sorry for myself, thinking,

eh, why me?

as if I was the only one stricken with such luck. But that afternoon when school let out, Gilbert stopped by again and told me the news.

“Today we were few,” he said. “Most of school dropped out as well.”

Out of seventy students, only twenty remained.

My own problems didn’t seem so important; the hunger belonged to the entire country. I decided to put faith in my father’s word, that once we made it through the hunger, everything would be okay. But first we had to make it through the hunger. And as Geoffrey had said, it was hard enough just worrying about tomorrow.

B

Y LATE

J

ANUARY, THE

GAGA

was finally gone. The people who’d depended on this for

nsima

turned instead to pumpkin leaves, and here the real starvation began. Famine arrived in Malawi.

It fell upon us like the great plagues of Egypt I’d read about, swiftly and without rest. As if overnight, people’s bodies began changing into horrible shapes. They were now scattered across the land by the thousands, scavenging the soil like animals. Far from home and away from their families, they began to die.

The same people I’d seen carrying their belongings to the trading center now stumbled past us in a daze, their eyes swimming in their sockets.

The hunger ravaged the body in two different ways. Some people wasted away until they looked like walking skeletons. Their necks became long and thin like the

dokowe

birds that drank near the river, not even strong enough to hold up their heads. Others were stricken with kwashiorkor, a dreadful condition a body gets when there are no proteins in the blood. Even as these people starved, their bellies, feet, and faces swelled with fluid like ticks filling with blood.

The starving people didn’t say much as they passed. It was as if they were already dead, yet still looking to fill their stomachs. They moved carefully along the roads and through the fields, picking up banana peels and discarded cobs and stuffing them into their mouths. Near my house, groups of men were digging up the

chikhawo

roots of banana trees so they could boil them like cassava. Some dug up other roots and tubers, even the grass from the roadside, and milled them into flour. Others resorted to eating the seeds from government starter packs, scrubbing off the pink and green insecticide that kept off the weevils. But it was impossible to get all the poison off, and many suffered from vomiting and diarrhea, which only made them weaker. Plus, having now eaten their seeds, they had nothing left to plant.

Every day the starving people stopped by our house and begged my father for help. I’d see them coming from far away and think, “Oh, this chap is looking fat. Finally someone who is doing well.” But once they arrived, I realized it was only the swelling.

The starving people saw we had iron sheets on the roof of one building and thought we were wealthy, even though our sheets were only fastened by stones. Some of the men had walked twenty and thirty miles.

“If you have one biscuit, please, I can work,” they’d say, their bare feet too swollen to wear sandals. “We’re now six days without eating. If you have just a small plate of

nsima?

”

“I have nothing,” my father had to say, “I’m barely feeding my family on one walkman.”

“Just give us porridge,” they demanded.

“I said no.”

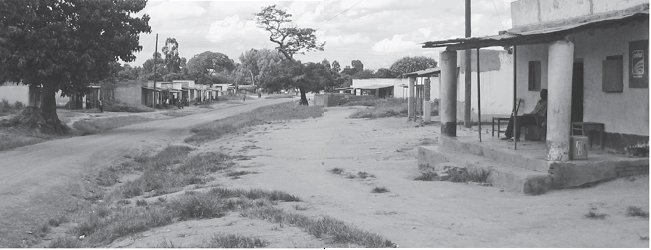

The Wimbe trading center, just near the primary school. The trading center became a kind of ghost town during the famine, despite being full of starving people.

Photographs courtesy of Bryan Mealer

A few men still chose to stay in our yard all night. The ground and wood were too wet for fires. When the rains came in the darkness, the men curled up under our porch and shivered. By morning they were gone.

A few nights later, we were seated outside having our meal when a man approached from the road. He was covered in mud and so thin it was hard to understand how he was even alive. His teeth poked out of his mouth and his hair was falling out. Without saying hello, he simply sat down beside us. Then, to my horror, he reached his dirty hands into our blob of

nsima

and ripped off a giant piece. All of us sat there in shock, saying nothing as he closed his eyes and chewed. He swallowed long and satisfyingly. When the food was safely in his stomach, he turned to my father.