The Boy Who The Set Fire and Other Stories

Read The Boy Who The Set Fire and Other Stories Online

Authors: Paul Bowles and Mohammed Mrabet

M

OHAMMED

M

RABET

Taped & Translated from the Morgrebi by

PAUL BOWLES

Black Sparrow Press

LOS ANGELES • 1974

Copyright ©1974 by Paul Bowles. All rights reserved.

Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews.

Grateful acknowledgment is given to the editors of the following magazines where some of these stories originally appeared:

Antaeus, Armadillo

,

Bastard Angel

,

The Great Society

,

Mediterranean Review

,

Omphalos

,

Rolling Stone

, and

Transatlantic Review

.

For information address

B

lack

S

parrow

P

ress

:

P.O. Box 25603

Los Angeles, CA, 90025.

ISBN

0-87685-175-8

ISBN

0-87685-174-X (pbk.)

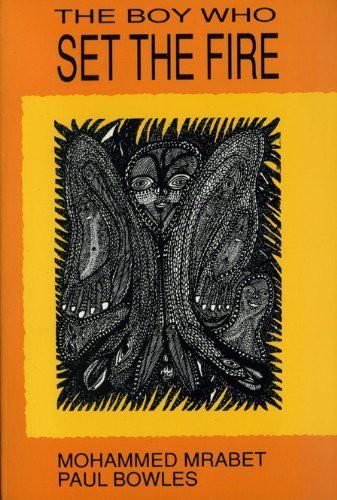

Cover illustration by Mohammed Mrabet

I

NTRODUCTION

Paul Bowles: Translations from the Moghrebi

By Mary Martin Rountree

S

TORIES

T

OLD BY

M

OHAMMED

M

RABET

The Witch of Bouiba Del Hallouf

A

PPENDICES

Paul Bowles/Mohammed Mrabet:

Translation, Transformation, and Transcultural Discourse

By Richard F. Patteson

Journey Through Morocco [1963]

By Paul Bowles

P

AUL

B

OWLES

was born in 1910 and studied music with composer Aaron Copland before moving to Tangier, Morocco, with his wife, Jane. His first novel,

The Sheltering Sky

, was a bestseller in the 1950s and was made into a film by Bernardo Bertolucci in 1990. Bowles’s prolific career included many musical compositions, novels, collections of short stories, and books of travel, poetry, and translations.

M

ohammed

M

rabet

(born in Tangier, 1936, real name Mohammed ben Chaib el Hajjem) is a Moroccan author artist and storyteller of the Ait Ouriaghel tribe in the Rif region. From 1946 to 1950, Mrabet worked as a caddy at the Royal Tangier Golf Club and thereafter as a fisherman, until 1956, when he met an American couple, Russ and Anne-Marie Reeves, at the Café Central in Tangier's Petit Socco, and remained friends with them for several years. They leased the Hotel Muneria (Tangier Inn) in Tangier and Mrabet worked there as a barman from 1956 to 1959, when he accompanied them to New York, where he stayed with them for several months. Upon his return to Tangier in 1960, he resumed his life as a fisherman and began to paint, (his earliest drawing known to originate in 1959) and met and became friends with Jane Bowles and Paul Bowles, the latter, who, being impressed by his storytelling skills, became the translator of his many prodigious oral tales, which were orated from a distinctive “kiffed” and utterly non-anglicized perspective and published into fourteen different books. Throughout the 1960s until 1992, Mrabet dictated his oral stories, (which Bowles translated into English) and continued work with his paintings. His books have been translated into many languages and in 1991, Philip Taaffe collaborated with Mrabet for the illustrations of his book “Chocolate Creams and Dollars.” Mrabet continues to paint and holds periodic art exhibitions, mostly in Spain and Tangier. He lives in the Souani area of Tangier, with his wife, children and grandchildren.

NTRODUCTION

By Mary Martin Rountree

F

rom the very beginning

of his residence in Morocco, his country of adoption, Paul Bowles wanted in some way to preserve expressions of the native folk culture. For years he sought, and eventually received, financial assistance from various foundations to carry out an ambitious project of recording Moroccan music. Beneath successive cultural layers superimposed by colonizing powers remained vestiges of ancient art forms that Bowles believed could lead him to the heart of the “hermetic mystery of Morocco.” Among those ancient art forms he placed the inventions, sometimes fabulous, sometimes comic, of the market storyteller, spinning out his tale to a group of listeners for whom the oral tale—even today in this technological age—supplies the chief source of entertainment. It was not until the 1950s, however, after living in Morocco for decades, that Bowles began to record the stories told by some of the young men in his circle of Arab friends.

In his preface to

Five Eyes

, a collection of stories by five different tellers, Bowles describes the beginnings of what would become for him an extremely important part of his literary activity:

I had first admired Ahmed Yacoubi’s [a painter and close friend whose work Bowles encouraged] stories as long ago as 1947, but it was not until 1952 that the idea occurred to me that I might be instrumental in preserving at least a few of them . . . . One day as Yacoubi began to speak, I seized a notebook and rapidly scribbled the English translation of a story . . . across its pages.

[

1

]

Although the young men were by no means traditional or professional storytellers, Bowles became increasingly convinced of the value of their tales as a repository of cultural memories, and with the purchase of a tape recorder in the mid-Fifties, he set about in earnest his work as a translator.

As early as the 1930s Bowles had encountered the challenges of translation so that he had in some measure already developed the skills he would need in this work. Fluent in French, Spanish, and Moghrebi (the Arabic dialect of Morocco), Bowles has numerous translations to his credit, particularly after he joined the board of editors of

View.

In his autobiography,

Without Stopping

(1972), he speaks of the work involved in his best-known translation, Jean-Paul Sartre’s

Huis Clos

, and of how the problem of finding precisely the right title for the play came to him from a sign in the New York subway:

No Exit

.

[

2

]

Both the number of Moghrebi translations he has published and the fact that Bowles has been steadily engaged in this activity since the mid-Fifties testify to the value Bowles sees in them. Thus far, he has edited and translated ten volumes of various kinds of narrative—short stories, novels, autobiographies, fables—the last one

The Beach Café and the Voice

by Mohammed Mrabet appearing in 1980. Although the narratives themselves spread over a wide range of tone, character, and plot, the Moroccan narrators all have in common the fact that they are illiterate. Bowles apparently believes that the illiteracy of his storytellers contributes to the power of their stories. He says:

I’m inclined to believe that illiteracy is a prerequisite. The readers and writers I’ve tested have lost the necessary immediacy of contact with the material. They seem less in touch with both their memory and their imagination than the illiterates.

[

3

]

Accordingly, the first Moroccan narrator to record extensively with Bowles was a watchman named Layachi Larbi, who uses the pseudonym Driss ben Hamed Charhadi. After Bowles had successfully translated and published a few of Charhadi’s anecdotes, Charhadi, elated by the money he made and eager to continue this odd kind of “work,” began to record almost daily with Bowles. The result is an entirely autobiographical account of Charhadi’s hardships in growing to adulthood. Although Lawrence Stewart refers to

A Life Full of Holes

as the first Moghrebi novel

[

4

]

, Bowles states that an editor at Grove Press, quite arbitrarily, “had the idea of presenting the volume as a novel rather than nonfiction, so that it would be eligible for a prize offered each year by an international group of publishers . . . .”

[

5

]

While

A Life Full of Holes

failed to win the prize, it was translated into several languages and earned Charhadi an encouraging sum of money.

A Life Full of Holes

, though simple and totally uncomplicated structurally, is nonetheless quite long and compelling in its detail, an altogether astonishing feat of sustained storytelling. Bowles accurately singles out Charhadi’s gifts in his introduction to

A Life Full of Holes

: “The good storyteller keeps the thread of his narrative almost equally taut at all points. This Charhadi accomplished, apparently without effort. He never hesitated; he never varied the intensity of his eloquence.”

[

6

]

The title of Charhadi’s autobiography comes from his own commentary on a Moghrebi saying—“Even a life full of holes, a life of nothing but waiting, is better than no life at all”—and this saying aptly describes the life of suffering, of enduring, of waiting for something better, if only a little better, that Charhadi’s tale unfolds. The story begins when the young protagonist Ahmed is eight years old. His mother marries a soldier, and the harsh, oppressive stepfather figures importantly throughout the boy’s life and is a heavy presence in the narratives of some of Bowles’s other storytellers as well.

A Life Full of Holes

is a painstaking depiction of a young Moroccan boy’s growth to manhood in a world of miserable poverty and deprivation, of cunning, violence, and treachery. During a journey, fraught with every conceivable difficulty, Ahmed’s mother turns to him at one point and says, “Ah, you see how hard life is!”

[

7

]

Generally speaking, this is the theme of the book, which is the story of stoic endurance of a life written by Allah. Charhadi describes the drudgery of the menial jobs Ahmed passes through in his struggle to earn enough to feed himself. From being a shepherd to work on a farm where he has a number of chores such as spreading cow dung to dry for winter fuel, he moves to the city where he gets a job as a “terrah,” a baker’s errand boy who fetches loaves of bread from houses to be baked at the oven, then returns them. For this he receives a piece of bread from each freshly baked loaf. At night he sleeps near the ovens. During this time Ahmed has the first of several jail experiences, this one occasioned by his cutting down trees to sell to “Nazarenes” (Christians) for Christmas. Charhadi’s account of his jail experiences are among the more remarkable episodes in the book. He re-creates the petty tyranny of sadistic guards, the intrigue and shabby power plays among the inmates, the tedium and hardship of their living conditions. The way in which the French authorities in the judicial system pit Moslem against Moslem adds yet another dimension to Ahmed’s sense of hopelessness. Never, however, does he indulge in self-pity. Though he rages against injustice around him, he accepts his fate patiently as a passage of time to be endured.