The Boyhood of Burglar Bill (10 page)

Read The Boyhood of Burglar Bill Online

Authors: Allan Ahlberg

Edna May, who’d had a solid game, picked up a loose ball and ran through the middle, reached Wyatt with a pass and he was off. Wyatt was difficult to tackle; tall and bony, he ran with a high knee action like a giraffe. Rutter tackled him and bounced off him. Higgs tackled him and missed. Charlie Cotterill tackled him, collided with him more like, and knocked him flying. Now, for a split second, the clock stopped. There was the smallest sliver of silence in the crowd, before the uproar. The players one and all turned their hopes and fears towards the referee.

‘Penalty!’

∗

I took the penalties, scored one already, as you may recall, in the Tividale match. Usually I sought to deceive the goalie, send him one way and the ball the other. On this occasion, though…

Ackerman stood on his line. Disconcertingly, about fifteen members of his extended family stood with him behind the goal and on either side. Worse still, all of them, every single one, had more or less

the same face;

the same round poppy eyes, the same sad, sweet, amiable expression. There was a dominant gene in there somewhere, I guess. Or God kept coming along stamping the identical design – like a pastry cutter – down on to the Ackerman baby-dough faces. It was like being asked to score against a family photograph, a tribe of goalies, all of whom – worser still – looked so mournful, you hardly had the heart to do it.

I stepped back. The crowd was hushed again; dogs barked, a baby laughed, Uncle Ike offered last-minute advice. I stepped up and hit the ball with all my might… straight at Ackerman.

17

Visible on Mars

Expectations in stories and books are unavoidable, aren’t they? As in life. In life we peer up ahead, down the road, trying to catch a glimpse of what’s in store, wondering. With a book, of course, you can flip the pages, sneak a look. You can tell when you’re near or not near ‘The End’ by the number of pages remaining. You must be expecting now, it’s only natural, for us to win: semi-final, final, cup, the lot. Why else would I write the book, tell the story? Well, as Tommy Ice Cream might have said, ‘Yeth… and noth.’ It’s more complicated than it seems.

I took the kick, straight at Ackerman. He, meanwhile, hurled himself with all

his

might out of the way, diving to where he thought the ball would go.

‘Goal!’

The desperate disappointment on the Ackerman family face was huge, visible on Mars. Our team celebrations were huge; no hugging or kissing, though, as previously explained.

Extra time (5–all)

. It was another cock-up in the Parks and Cemeteries department. The half-past five kick-off made no allowance for the possibility of extra time, ten minutes each way. We should’ve kicked off at five or five fifteen. Anyway, there we were, lining up once more in the gathering gloom. Matches flared on the touchlines as cigarettes and pipes were lit, traffic blazed on the Birmingham Road, the sky was an ever deeper blue with a line of rusty red and duck-egg green over the Rounds Green hills.

But we played. Truth is, we were not unused to such conditions. Our games in Albert Park often only stopped when Mr Phipps or the park bell drove us out. On winter evenings we played in the street with just a street lamp for illumination, or car headlight! So, ten minutes each way. I guess by now we must have been slowing down, but it didn’t feel like it. We were steaming like horses and yelling to each other, playing by sound as much as sight, while the crowd groaned and whistled and crept ever further out on to the pitch itself, gazing after

the ball. Vincent Loveridge had cut his head scoring that goal and had a plaster over his eyebrow. He looked more debonair than ever, like Errol Flynn, if you have heard of him. Amos was rampaging around in a swarm of swearwords, getting chastised, ‘Language, language’, by the referee.

And it got darker still. And Malcolm headed (or got his head in the way of) a fierce shot from Rutter. The ball rebounded for a throw-in! Malcolm ended up in the back of the net stunned,

concussed

. He was carried off and tended to by his frantic mother and auntie; got a face-licking later on from Rufus – the dog, that is, not Toomey. Down to ten men but it hardly mattered. The pitch was shrinking as the crowd snuck in; time was trickling if not water-falling away. Tick, tick. And now the sky was seeping into the earth, the horizon gone, no colour whatsoever in the grass. A flurry of starlings swooped and wheeled above us. Things became mysterious.

With a minute to go, the ball arrived in Tommy Ice Cream’s hands. He held on to it for a moment. ‘Belt it, Tommy!’ yelled Spencer from behind the goal. Then, more softly, ‘Belt it.’

Tommy belted it, whereupon it rose high into the night and disappeared. Players ran here and there, peering anxiously upwards like Chicken-Licken,

colliding, some of ’em. And down it came – that ball, that lovely ball! – bounced once over Tommy Gray and once again over the advancing Ackerman, and… where was it?

It was like the

SPOT THE BALL

competition in the

Sports Argus

, though by now it was so dark you could’ve played spot the players, spot the pitch. Where

was

it? And then we spotted it.

‘It’s in the net.’ (Wonder.)

‘Ref, ref!’

‘It’s in the net!’

The referee approached the near-invisible goal, bent low, squinted and blew his whistle.

It was in the net.

18

The Boy Who Went Berserk

The most common torture is to ‘do a barley-sugar’, also expressed verbally in the threat ‘I’ll barley-sugar you’, which is to twist a person’s arm round until it hurts, usually behind his back, so that the sufferer has – according to which way his arm is being twisted – to lean backwards or bend forwards excessively to alleviate the pain, and is thus utterly at his tormentor’s mercy. The hold is also known as ‘Red hot poker’, ‘Fireman’s torture’, and ‘Nelson’s grip’.

Iona and Peter Opie,

The Lore and Language of Schoolchildren

(1959)

I will tell you now the best, most memorable part of this whole business, this boyhood of mine. It was the Friday, the day following our famous victory. I was in Tugg Street on my way back from

running an errand for Mrs Moore. Six o’clock or so. Soot in the air from a chimney on fire. A light drizzle falling. In Tugg Street, yes, with a sack of firewood, separate bundles, that is, bound with wire. Not so heavy, but lumpy and awkward to carry. I had paused to adjust my load while gazing into Starkey’s window. And somebody passed me in the street. And spoke.

The day had begun, in my case, at six in the morning. There was no way I could sleep. I was up and, rarest of events, having breakfast with my dad. He was a fitter’s mate at Crosby’s, a labourer really; his hourly rate so pitifully low he had to put in all the hours God sent – a million a year! – to make a living wage. Even then we needed Mum’s living wage to get by.

My Dad

. A labourer, yes, but the possessor of delicate skills nonetheless. His hobby was fretwork. Late evening and into the night he would cut out the most intricate designs in wood with his treadle-operated fretsaw, glasses on the end of his nose, peering like a professor. (I still have a sewing basket that he made for Mum.) He made lead soldiers too, horsemen and such, pouring the molten metal into moulds, painting their uniforms and features

with the steadiest hand and the finest brush. He made them for me.

It was a dazzling morning. I took Dinah up the park and we were so early the gates were still locked. We had to burrow our way in through a gap in the hedge. The park looked altogether unused, still in its cellophane wrapping of dew. Ducks, heads under their wings, dreamed away at the edge of the untouched and slightly steaming pond, till Dinah’s lumbering attentions sent them quacking and splashing away. I sat in the sheds eating a lukewarm sausage, gift from Dad. Dinah looked hopeful but didn’t get any. I climbed a tree or two; the season for climbing trees was fast approaching. Climbed

the

tree, probably, walking up it a little way, at least, for the view.

On the way to school with Spencer and Joey we gradually accumulated a gang of ‘supporters’, mainly infants, all frothing over at any excuse for wildness. I experienced again that curious mixture of feelings: pride, exhilaration, shyness. After the match, Mr Cork, with a face like a brick wall, had come charging into our changing room. We flinched, half expecting a cricket stump to come crashing down. Whereupon, with what might have been a smile and looking distinctly embarrassed

himself, he mumbled something, shook hands with Wyatt and patted Tommy Pye on the head. Mr Reynolds was behind him in the doorway. ‘Yes, well done, lads!’ he called out. ‘And lasses!’ added Mrs Prosser, behind him.

Friday morning, then, and so much to talk about (all of it already talked about) and talk about again. We needed to

hear

it, this story of ours, from each other, from ourselves. Hold it in our minds, shore it up against the never-ending onslaught of events, the wear and tear of time.

‘That goal of Tommy’s!’

‘Which Tommy?’

‘Which goal?’

‘A bomb from the skies, my uncle called it.’

‘Spencer told ’im to do it.’

‘That header of Malky’s!’

‘Knocked ’im flyin’!’

‘Knocked ’im out.’

‘Knocked them out… sort of.’

We were running the film in our heads, comparing the versions, and backwards, so it seemed, from Tommy Ice Cream’s already mythical kick, the edited highlights in reverse.

There were no assemblies on Fridays. Classes had prayers in their own rooms with their own teachers.

In Miss Palmer’s we sat at our desks with hands together and eyes closed. A semi-religious thought somehow smuggled its way into my head. I had spent my Sunday School collection money on a sherbet dip from Milward’s. Money from my mother’s purse, Dennis Johnson’s marbles, God’s collection. (Sorry, God.)

Miss Palmer’s room was special: it had a slope, a rake like a lecture room or theatre. Leaving your place and standing next to the teacher’s desk was like going on stage or entering a bullring. The desks were the usual type, worn and polished wood, black metal, integrated inkwells. There were rows of doubles down the middle and singles down the sides.

Miss Palmer, to be fair, was not a bad teacher. She had a habit, though, of mobilizing the other children against you when work or behaviour was not to her liking.

‘What do you think of this,

4

A? Hm? Shameful.’

4

A. Yes, we were the clever class, supposedly, 11+ candidates: Spencer, Trevor, me; not Joey surprisingly, or Monica more’s the pity.

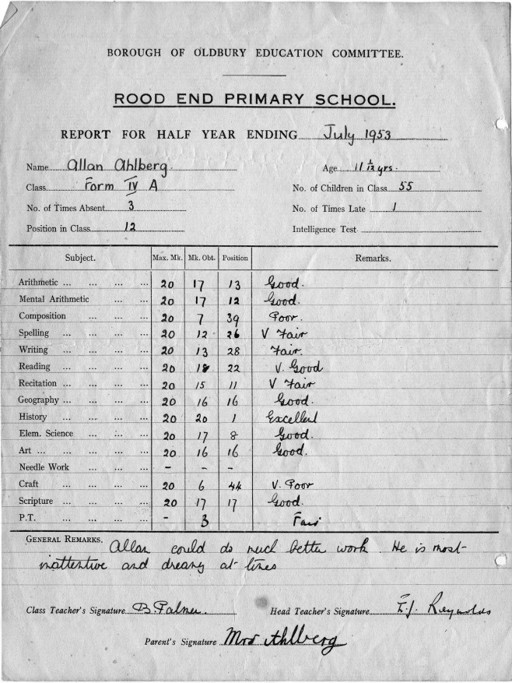

My memories of classroom life, the actual lessons and such, have faded. The playground and the park are much more vivid. However, I still possess, found in that box of my mother’s things, a slim green folder. It has my best eleven-year-old’s writing on the front.

School Reports

, it says, and my name. And here it all is: number of times absent, number of times late. Subjects – marks obtained – position in class. General remarks, ‘Inattentive and dreamy at times’. My mother’s clumsy signature at the bottom.

The subjects we were taught in those days included the usual: Arithmetic, Spelling, Reading, Composition. Miss Palmer, I see, placed me 39th in the class for Composition: marks obtained, 7 out of 20. Oh dear, and here I am now writing,

composing

a whole book. And she’s in it.

One

un

usual subject was Recitation. For Recitation you had to learn a poem, stand beside the teacher’s desk and recite it to her. Spencer, I remember, despite his shyness, was brilliant at this:

My room’s a square and candle-lighted boat,

In the surrounding depths of night afloat.

My windows are the portholes, and the seas

The sound of rain on the dark apple-trees.

Frances Cornford

I wasn’t bad myself, it seems: position in class 11th; marks obtained, 15 out of 20. Of course, all my

best subjects were missing from these reports.

Alibis:

marks obtained, 20 out of 20.

Climbing Trees:

position in class, top.

Playtime came and we returned to more important matters.

‘If y’picked a team…’ Spencer was developing a line of thought.

‘That penalty!’ So was I.

‘The best players…’

‘It’s called a double bluff!’

‘From their team and our team…’

‘See, I really fooled ’im.’

‘You’d be in it.’

Spencer had my attention. The combined best team, it was an interesting idea.

‘Joey’d be in it,’ I said.

‘Him too.’

‘Tommy Pye!’

‘Tommy Ice Cream.’

‘Wyatt!’

How peculiar. There was I thinking how could we have won, when all the while the bigger, better question was, how could we have lost? Five of us, and Tommy Pye was the best of the best, and Tommy Ice Cream the biggest of the best. They had Vincent the Invincible, Amos, a whirlwind of fearless muscle,

Tommy Gray, Rutter, Higgsy. And we had…