The Brea File (21 page)

Authors: Louis Charbonneau

Another thick sheaf of reports detailed the activities of agents Wagner and Rayburn in trying to locate the youth who had stolen the FBI vehicle—and, Macimer believed, the Brea file. Macimer decided to assign some of the squad’s new arrivals to the search for the missing auto thief. Wagner and Rayburn would continue to concentrate on the Fedco department store and its environs.

Other teams would direct more attention to the area of the youth’s escape after ditching the stolen car.

Macimer turned to the preliminary lab report received that morning from FBI Headquarters. It described the findings yielded by analysis of the stains on the sheets Macimer had sent over to the FBI Lab. In addition to tests of the semen stains, the sheets had also been examined by the Latent Fingerprint Analysis Unit, using laser equipment in an attempt to bring out fingerprints that were otherwise undetectable. Predictably, the fingerprint examination had been unproductive; Xavier

did

wear his gloves in bed. The lab’s analysis of the stains, however, was another story, and Macimer studied the report with quickening hope.

Macimer called in agents Rodriguez and Singleton, the two Spanish-speaking agents he had recruited from the New York office. He handed them the lab report and waited in silence while both agents scanned it. Singleton, he remembered, had majored in biology at the University of Cincinnati before deciding that she would rather employ her flair for languages and a relish for challenges in an unexpected direction: an FBI career. She was among the large numbers of female agents recruited during Director William Webster’s tenure.

“Well, where does that report get us?” Macimer asked finally.

Rodriguez shrugged. “Maybe you should ask my partner,” he suggested.

Singleton regarded him coolly before she said, “El chauvinist thinks I’m going to turn pale using the word ‘semen.’ The truth is, he’s not sure what the report proves.”

“Hey—!” Rodriguez protested.

“What it comes down to is this,” Singleton went on. “There are over three hundred genetic markers on human red blood cells. A few of these are present as soluble substances in body fluids, such as semen. That means you can perform tests on semen stains, even old ones, that enable you to identify the blood type of the person responsible.” She glanced down at the FBI Lab report, which she was still holding. “The lab used two different enzyme tests, both the commonly used acid phosphatase test and the LAP color reaction test, to verify that the stains found on the sheets were human semen. Then they used the agglutinin inhibition test to determine the blood type of the individual.” She paused as she glanced again at the report. “That’s where we got lucky. Our subject has a rare blood type, A

1

B.”

FEDERAL BUREAU OF IDENTIFICATION LABORATORY REPORT

File No.

431

SUBJECT: Identification of stains on Exhibit A.

DATE: June 7, 1984

Tests were conducted on sheets (Exhibit A) of polycotton material. Ultraviolet light was used to locate stained areas. Greenish coloration indicated probability of semen. Microscopic examination for detection of spermatozoa was positive but not conclusive because no spermatozoa were found intact. The follow tests were then performed:

(A) Walker acid phosphatase test. Male ejaculate produces a high acid phosphatase activity as compared with other body fluids such as saliva, urine, etc. Test result was positive.

(B) The LAP test. This is a qualitative color reaction test based on a histochemical technique for demonstrating the presence of leucine aminopeptidase (LAP), which is more abundant in human semen than in any other body fluid or animal semen. Test result positive.

(C) Precipitin test was performed to verify that the semen stain was derived from a human source. Test result positive.

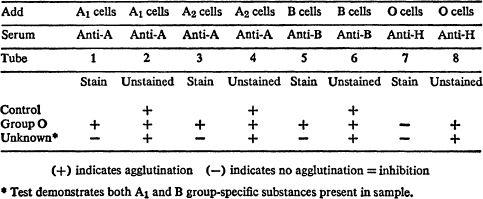

(D) Precipitin test was performed using known reagents and control to determine blood group of the person from whom the seminal stain was derived. Tests were conducted of unstained material (from Exhibit A), known group O blood sample, and the subject stains. This test is based on the fact that group-specific substances in blood are able to neutralize their corresponding agglutinin in a serum. Test results shown in table.

TABLE 1. RESULTS OF INHIBITION TEST TO DETERMINE BLOOD GROUP

“How rare?” Macimer asked quickly.

“About three percent of the population. That applies to both Europoids and those of African descent. I imagine the same percentage would hold true for Cubans and other Hispanics, but we can verify that.”

Rodriguez was staring at his partner with new respect. Macimer repressed a smile and said, “So… we have a young man, probably Cuban, certainly not American-born, about seventeen years of age, with a rare blood type. Any ideas on how we find him?”

Rodriguez shifted nervously in his chair—anxious, Macimer guessed, to recover some lost face. He pursed his lips so that his bandido mustache drooped even more. “Suppose he was one of the boat people who came over in 1980, the ones Castro wanted to get rid of, a lot of them troublemakers. He’d have been through one of the camps. We have complete records on all those people. That ought to include blood types.” There had been the suspicion at the time that Castro might have planted agents of his own among the refugees. All had been closely scrutinized by the FBI. And there would be medical records, Macimer thought.

“That’s a long shot,” he said.

“Maybe not so long.” Jo Singleton shot a glance of approval at her partner. “We haven’t exactly had what you’d call a regular immigration quota from Cuba since the Bay of Pigs, which happened before this Xavier was born. So if he’s Cuban, and he wasn’t born in this country, there’s a good chance the only way he could have got here was with the boat people, given his age. He would have been thirteen, fourteen at the time if he’s seventeen or eighteen now. There shouldn’t be too many in all those records that meet all the criteria of the profile you just gave us.”

“There were thousands of those boat people—”

“But only a small number were young children,” Singleton said. “Eliminate all the adults and younger children, and all the females, and you’re probably down to only a few hundred possibilities. And with a blood type that rare, there shouldn’t be more than a handful that fit the profile.”

“If Xavier was one of the boat people,” said Macimer.

“It’s worth a try. And if we do find him, that report gives us a positive identification. He won’t be able to claim he didn’t use your sheets.”

Macimer smiled. “Why not?”

“Those stains. Identification of special antigens in the stain means you can match them up with red blood cell antigens. Take a blood sample from Xavier, and if the antigens match, the chances of identification are something like two million to one, if I remember my lessons.”

“You seem to be doing pretty well,” Macimer said. “Okay, go to it. Find Xavier for me.”

* * * *

In San Timoteo, California, Pat Garvey and Lenny Collins met by prearrangement at one o’clock that Friday afternoon at the Burger King out on the highway to Sacramento. California seemed to be distinguished more by the number of fast-food outlets than by surviving palm trees. It was another hot, dry day, the temperature in the mid-eighties.

Over hamburgers and french fries and chocolate milk shakes the two agents reviewed their three days in San Timoteo. Both thought they had accomplished as much as they could in the town. Lippert’s investigation must have taken him further afield, Garvey suggested. To find out where, they would have to follow him elsewhere. “I’d say we start digging into the records of the PRC Task Force. There’s a copy of that file in Sacramento. That was the office of origin for that investigation.”

“There’s also a copy at FBI Headquarters.”

“But we might see something that anyone who hasn’t been dogging Lippert’s footsteps would miss.”

“You’re probably right, but… there’s one thing I’d like to do first, if we’re all wrapped up here.” Collins had reached the bottom of his milk shake and made sucking noises with his straw as he tried to get the last drops. “I’d like to have a look at Lake Hieronimo. Have you thought any about Vernon Lippert drowning when he did?”

“You mean when he was just about ready to retire. Yeah… it’s ironic. You work your ass off all your life, and just when you’re about to reach the point where all you have to do is go fishing, your boat springs a leak or the wind comes up and you’re wiped out.”

“That isn’t what I meant. I meant… how many FBI agents do you suppose there are who drown alone in the middle of a little fishing lake? What do you suppose the statistics are on that?”

Garvey stared at him. “I doubt there are any,” he said after a moment.

“Right.” Collins drawled out the word. “I’d kind of like to wander up there, maybe talk to a few people, the coroner, people who live there year-round. There must be a few.”

“You think there’s something fishy about that lake besides the fishing?”

Collins gave up trying to extract any more chocolate from the bottom of the shake cup. “Could be. I looked up Lake Hieronimo on the map. It’s maybe an hour’s drive up into the mountains. Probably cooler up there. We could make it this afternoon, then let the boss decide what comes next. That is, if you’d like a break from all the excitement around here.”

“Why not?” Garvey was playing it cool but Collins caught the sharp interest in his eyes.

“You ever do any fishing?” Collins asked.

“Are you kidding? I grew up in a boat.” Garvey laughed at Collins’ transparent surprise. “What did you think, that I grew up playing backgammon in a private school? Or polo?”

Collins grinned to cover the surprise of his perception that there might be more to his partner than the All-American façade suggested. “Polo crossed my mind,” he said.

After going off duty, Harrison Stearns spent that Friday evening in and around the Fedco department store. He knew his SAC was convinced that the thief who had taken Stearns’s vehicle three weeks ago was not a stray in the area. He either lived or worked nearby; otherwise, what had he been doing there on a rainy night without transportation of his own? “If you have to go any distance to go shopping without a car,” Macimer had said, “you don’t pick a rainy Friday night.”

But Agents Rayburn and Wagner had already checked out all Fedco employees, paying close attention to any who had recently been fired or quit. None of them fitted the description of the auto thief.

He lives near here, Stearns told himself. Or he works somewhere else close by. And gets off work late.

That speculation narrowed the scope of the search. But there were no offices or small businesses in the area that let employees out around eight or nine at night. The kid might be a busboy at a McDonald’s or a supermarket, or—

Or a thief.

Stearns, who at that moment was in the television and stereo sales area of the big discount store, watching the crowds, withdrew into a corner with his new idea. He began to get excited. Suppose it was no accident that the kid was in the parking lot that night? Suppose he wasn’t really an auto thief but a small-time scavenger, one who worked the parking lots, the cars that were left unlocked?

Would he feel safe enough, after three weeks, to come back here again?

Stearns reacted gloomily. Putting himself in the thief’s shoes, he could not see himself returning so soon to the scene of this particular crime.

But there were other crowded parking lots not far away. A group of stores nested around that intersection to the west, less than a half mile from Fedco. A restaurant on another corner, even closer. It had valet parking, but the kids chasing the cars didn’t have time to pay attention to loiterers—not discreet ones. And a parking-lot thief, usually bent only on stealing loose packages or car stereo units, was small-time enough to panic if he actually stole a car and belatedly discovered that it was a police car. Even worse, an FBI vehicle.

Leaving Fedco, Stearns located his own car and drove a half mile down the street to the next traffic light. There he turned into the parking lot serving a group of stores clustered around a Walgreen’s and a supermarket. When he got back to the office, he thought, he would check out any reports of parking-lot thefts. Might have to ask for police reports covering thefts in this vicinity; reports of petty thievery might not get past the first basket.

From a back corner of the lot, hunched down in the passenger seat of his unmarked car—anyone checking a parked car to see if it was occupied instinctively looked at the driver’s seat—Stearns began his own private surveillance.

* * * *

Back at Fedco, Jack Wagner and Cal Rayburn bought a cheese and pepperoni pizza in the cafeteria and carried it to one of the undersized Formica-topped tables. While Rayburn carefully wiped debris left by the previous occupant from the table, Wagner folded a wedge carefully and brought it to his mouth. Through a mouthful of pizza he said, “What do you suppose Stearns was doing here? Free-lancing?”