The Broken Land (12 page)

Authors: W. Michael Gear

Tags: #Fiction, #Sagas, #Historical, #Native American & Aboriginal

I run a hand through my long black hair. “Yes, I do.”

“This war only makes it worse,” Kanadesego says. “Are we all fools?”

I cannot find the will to respond. The answer seems obvious. Finally, I say, “Why don’t the clan matrons stop it? The easy answer is to end the war, pool our food, and give our Healers everything they need to fight the witchery.”

Pandurata laughs out loud. Her eyes blaze when she looks at me. “Don’t be silly. They don’t wish to stop it. They want to destroy their enemies. Vengeance has become life. That’s all. We are like packs of lost souls, forever seeking revenge. Little more than half-human beasts.” She lifts a hand to her trembling lips.

Kanadesego slips his arm around her shoulders and pulls her close. “That’s why we’re here. We’re going to help end it.”

I have witnessed many horrors, more than I will ever be able to silence, including unexplained diseases that maraud through starving villages leaving husks of human beings behind to Sing death Songs over their own children. But witchery on the scale they describe seems impossible. Our people recognize three types of illness. Illness from natural causes can be cured by herbs, incisions, poultices, and profuse sweating. Illness caused by unfulfilled desires of the soul—of which the patient might not even be aware—can be cured by ascertaining and fulfilling the soul’s desires. The third cause is the most insidious: witchcraft. Witchery can only be cured if the Healer discovers and removes all the spells or charms that have been shot into a person’s body.

“Where are the Healers?” I ask.

“Oh, they died first. They ran from village to village with their Healing bags, tending the sick, until they, too, were overpowered by the witchery. There’s no one left to Heal.”

I don’t believe it. Especially if the illness is racing across the nations, many Healers would rise to take the places of those who’d perished. She can’t be right.

“It was all foretold,” Kanadesego said, smiling again. “It’s coming true. The world will be left clean and new. Humans will be better, smarter, next time. We won’t destroy ourselves ever again.”

A crow flaps overhead, cawing. I flinch. We all look up to watch its black body sailing through the trees. When it disappears amid the shadows an eerie feeling of clarity steals through me. I understand at last the petals of light that fall through my Dream.

I rise. “I thank you for your kindness. I was hungry and you fed me, though I know you must have very little left for yourselves. I won’t forget you.”

“You should stay here with us,” Kanadesego calls. “You should wait, just wait. It will all be over soon.”

“Thank you, but I must get home.” I gesture to the bones. “To collect the remains of my own loved ones.”

They seem to understand this. They both nod approvingly.

“Good luck, then!”

I start up the trail with Gitchi at my heel, and they both lift their hands. Pandurata calls, “May you find the end before it finds you, friend.”

Just before I climb the next rise in the trail, I hear Pandurata Singing. I look back. Kanadesego’s deep voice joins hers. They are sitting alone on the log Singing the death Song over their ancestors’ bones.

I stare.

The human False Face is riding the winds of destruction. Nations are crumbling. Starvation stalks the land, and sorcerers have loosed a mysterious evil that is laying waste to one village after another. It’s all crashing down.

Yet they sound so happy.

Sky Messenger

B

rilliant sunlight strikes my eyes as I walk the main trail toward the Yellowtail Village palisade, built of upright logs that stand forty hands tall. Sentries move along the catwalk at the top, just their heads and shoulders showing. By now they have seen me and notified War Chief Deru that a lone man is approaching.

As I pass the large marsh, Reed Marsh, that swings around the northern and western sides of the sister villages, Yellowtail and Bur Oak, I study the dense stands of cattails. Those closest to the shore, the easiest to gather, have been harvested. My people weave the leaves into mats and pound the roots to jelly to use as poultices on wounds, sores, and burns. The soft downy fuzz from the mature flowers is used to prevent chafing in babies, and absorb menstrual blood. The young flower heads stop diarrhea. We also eat the shoots, pollen, roots, and stamens. The entire plant is so useful I am puzzled that thousands of stalks in the middle of the marsh remain standing tall and straight. Has the fever struck here? Is that why the harvest is not yet completed? Soon the seedpods will burst and be carried away in the wind. They will be lost.

I continue walking. Blood begins to pound in my ears.

Ice skims the surface of the marsh. An empty muskrat house sits in the middle, the occupant long ago thrown into some stew pot. Soon the stems will be scavenged for firewood. Given the cold, I’m surprised it hasn’t already been collected. I—

A shout goes up, and my gaze returns to the catwalk. Warriors are running, calling to each other. The commotion increases when I stride directly for the closed palisade gates.

“It’s him and his wolf!”

a man shouts.

“I’d know his walk anywhere!”

“It can’t be. There’s a death sentence on his head. No man wishes to be executed by his own relatives.”

I keep walking. When I stand before the gates, I look up at the warriors on the catwalk. Their eyes are wide with surprise. Some aim arrows down at me, debating whether or not to shoot me on sight. I know every face. I call, “Wampa, please inform Matron Jigonsaseh that her grandson wishes to address the Matron’s Council.”

K

oracoo dipped the soft hide into the water bowl again and wrung it out. All down the Bear Clan longhouse people muttered darkly or thrashed in their sleep, tended by exhausted relatives. The fever had come to Yellowtail Village seven days ago and swept through the longhouses like wildfire. The nauseating smell of vomit and loose bowels permeated the smoky air.

Two compartments away, the great Healer, old Bahna, sprinkled a man with water, then used a turkey tail to fan him. Healers had been working nonstop, but half the village was down. Forty-two dead. Bahna Sang softly. The lilting words of the Healing Song rose into the air like golden wings, soothing every person who could hear them.

Koracoo bent over and washed her mother’s fiery face with the cool cloth. “Mother, try to sleep.”

Matron Jigonsaseh, leader of the Matron’s Council of Yellowtail Village, whispered, “Too much … to think about … fever … all the refugees. We’re … vulnerable.”

“Our warriors are prepared, Mother. Don’t worry. I spoke with Kittle only yesterday. Every person able to carry a weapon knows he or she may be called at any moment to defend the five allied villages.”

Koracoo smoothed the cloth over her mother’s forehead. Long gray hair streamed around Jigonsaseh’s face and looked stark against the black bear hide that covered her frail body. Sickness rattled in her lungs. In the past two days, her breathing had grown labored, as though there weren’t enough air in the world. Koracoo dipped the hide again, wrung it out. Her heart ached.

When Mother closed her eyes, Koracoo leaned back and took a deep breath. A commotion had risen outside. Warriors called to each other on the catwalks. Feet pounded the plaza.

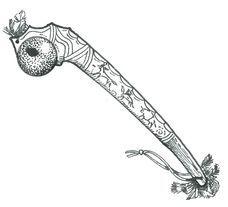

The instincts of ten summers as a war chief kicked in. Koracoo reached for her war club: CorpseEye. Firelight gilded the copper inlay in club, giving it an edge of flame. She smoothed her fingers over the dark, dense wood. He was old, very old. He had been passed down through her family for generations, each new warrior entrusted with the task of caring for the club’s soul. Legend said that CorpseEye had once belonged to Sky Woman herself. Strange images were carved on the shaft: antlered wolves, winged tortoises, and prancing buffalo. A red quartzite cobble was tied to the top of the club, making it a very deadly weapon—one Koracoo wielded with great expertise.

She shoved to her feet just as her daughter, Tutelo, burst through the leather hanging and stood breathing hard, her eyes wide, as though with shock.

Koracoo said, “What is it? What’s happened?”

“Mother …” Tutelo wet her lips. She was a pretty young woman with an oval face and long black hair that hung to the middle of her back. Sweat beaded on her small nose. She’d run hard to get here. “He’s alive.”

“Who’s alive?

“Sky Messenger, he—”

Koracoo reached out, and her fingers sank into her daughter’s shoulder. “Where is he? Tell me quickly.” Blood roared in her ears.

“At the gates. He asked to speak with Grandmother and the Matron’s Council.”

“Blessed Spirits, he must not know that Kittle has—”

“Koracoo,” Jigonsaseh whispered.

Koracoo spun around to look at her mother. Jigonsaseh lifted a clawlike hand. “Send a runner to Kittle … . Ask her to give us … one day to …” Her words were cut short by a violent coughing fit that racked her body.

Koracoo turned back to Tutelo. “Go to Kittle, ask her to give us one day to hear Sky Messenger’s story before she carries out her execution order. Hurry.”

Tutelo threw back the entry curtain and ran, vanishing into the daylight. Koracoo swung her foxhide cape around her shoulders and ducked outside carrying CorpseEye. People crowded the plaza, most of them refugees from devastated villages. Many carried baskets. Others raced around collecting things: rocks, potsherds, anything they could throw.

Koracoo stalked toward the gates like a hunting lynx, her muscles rippling, ready to do battle if necessary. He might be a traitor. No one knew for certain, but even if he was, he was still her son. Tomorrow she may have to club him to death herself, but it would not happen today. Not if she could stop it.

When War Chief Deru saw her approaching, he shoved a man aside. “Make room for the Speaker for the Women.”

Like a school of fish at a thrown rock, people scattered, leaving a path for her. Ahead, she saw her son standing with his hands tied behind his back, surrounded by eight burly warriors. They looked as stunned as she probably did. Like everyone else, she’d assumed he was dead.

Koracoo strode up to stand less than six hands from him, and Sky Messenger clamped his jaw. “Mother, just give me one hand of time. You must hear what I have to say.”

Gitchi, who stood at his heels, let out a low growl and bared his fangs, warning her to come no closer. When a warrior lifted his club to kill the dog, Koracoo said, “No.” The man instantly lowered his weapon.

She stared at her son. Facing her was not easy for him, she could tell, but he did it unflinchingly. They gazed at each other eye to eye. The soot of many campfires streaked his round face. His breathing was shallow, his lips pressed into a tight line, but his brown eyes blazed with defiance.

In a powerful voice, he called to the crowd, “I know how the world dies! Do you care to know? Does anyone in this village want to hear my vision? Does anyone want to help me stop it?”

The crowd went silent, waiting for Koracoo’s response. But an eddy of awed whispers moved across the plaza.

She studied Sky Messenger’s blazing eyes. She’d seen that look for the first time twelve summers ago. He’d just become a man. The body of his enemy lay upon the snow-covered ground before him. That look was a kind of righteous terror. The look of a man who’d just accepted a mission that would lay waste to his world.

She said only, “Bring him.”

As she strode back for the Bear Clan longhouse, villagers lined up to shout curses and pelt Sky Messenger with potsherds, rocks, dog feces—anything they’d collected. He grunted when the largest stones struck him, but said nothing.

O

ne hand of time later, I sit before the fire in the middle of the Bear Clan longhouse. My hands and feet are bound. Mother sits to my right, with her war club, CorpseEye, resting across her lap. The red chert cobble hafted to the tip has two black spots, glistening eyes that stare at me. If the council so decides, it will be Mother’s responsibility to kill me.