The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss (53 page)

Read The Brotherhood of the Screaming Abyss Online

Authors: Dennis McKenna

I briefly lost consciousness. When I came to, I assessed the situation. The top of the trench was a couple feet above my head, and I had broken something. It was very painful to stand; I couldn’t put all my weight on my left leg. I realized I had pushed the only barrier to the trench out of the way, meaning another cyclist was very likely to plunge in on top of me. I started to shout as loud as I could and shined my bike light out of the trench. In fact, what I had feared was narrowly averted; another botany graduate student was a few minutes behind me on the trail. He heard my screams and helped me get out of the trench. Another rider soon headed off to call an ambulance.

I had a hairline pelvic fracture, a concussion, and compressed vertebrae. I spent the next two weeks Vancouver General Hospital, my first introduction to the Canadian health care system. The final bill for the excellent treatment I got there totaled $7.50. In today’s acrimonious political climate, American conservatives love to bash the Canadian health care system, but it has provided high-quality universal coverage for all Canadians (and American students) since 1962. I find it sickening that our country has yet to enact something as effective, and probably never will.

My injuries called for bed rest followed by physical therapy. Seeing as how I was in the process of failing organic chemistry, my hospital stay provided a graceful exit from that dilemma. When I got out, I remained on crutches for eight weeks and had daily physical therapy. I also resumed practicing yoga, as I had been doing in Hawaii, and that may have accelerated my recovery. I was still in a lot of pain, and couldn’t easily get around on my crutches, so I tended to hole up in my cold and damp apartment, covered in blankets. Occasionally, I’d get the energy to drive to campus and check my mail. I’m sure I cut a pathetic figure as I hobbled into the botany department mailroom. At least one person seemed to think so, a cute graduate student named Sheila with beautiful long red hair. I was struck by her and tried not to show it, but we exchanged friendly greetings.

As the winter and spring wore on, I gradually recovered. I continued to stay home a lot studying for my comprehensive exams, which I passed without incident in May. In July, the department hosted Botany 80, a large conference that brought in more than a thousand botanists from around the world, including some of my colleagues and friends from Hawaii. As students in the host department, we were enlisted to help with logistics. My job was to greet arriving dignitaries at the Vancouver airport, and I was surprised and delighted to find that Sheila had been assigned to the same group. Typically, I broke the ice by bumming a cigarette. With little to do except hang at the airport waiting for various flights to arrive, we had time to get to know each other. She was currently in a master’s program studying algae under Dr. Bob DeWreede, who had studied under Maxwell Doty, a notoriously tyrannical phycologist at the University of Hawaii.

At the same time that Botany 80 was in full swing, so was the Vancouver Folk Festival, one of the biggest such events in North America. On a slow night at the conference I decided to check out the festival. I remembered Sheila mentioning she liked folk music, and I was hoping I might run into her there, though that seemed unlikely in a crowd of 10,000. As it happened, I’d only been there half an hour when I literally stumbled over her sitting on a blanket in front of the main stage. And she was alone. I knew she’d recently been going out with a fellow botany student, but his tastes apparently ran more to classical music rather than folk; so there she was, a lovely

and

unaccompanied redhead. I pretended to be nonchalant about it, but my wish had come true.

We soon moved to the edge of the crowd and fell into conversation, sharing our life stories. Sheila had grown up in the interior of British Columbia, the daughter of a rancher outside of Kamloops. She had three siblings: a sister about fourteen years older, a brother about nine years older, and another sister two years younger. Many of her experiences growing up were not unlike mine in Paonia, although she’d lived on a ranch and I was what she called a “townie.” She was a bookworm like me and had a quick mind and strong opinions. She loved to argue, I quickly learned, and was a good match in conversational give-and-take. We both were children of the sixties who had done our time in hippie houses and been influenced by the counterculture. We talked to the end of the concert and then reluctantly parted.

It was clear there was a deep resonance between us. I at least was intrigued and wanted to see her again as soon as possible, all the more so when I learned that she and her boyfriend were breaking up. By mid-August I’d moved again, to a different part of Point Grey. I invited Sheila over to hang out, and she ended up spending the night. That was the start of something, but I wasn’t sure what. I had no idea she’d become my wife or that one day we’d be the proud parents of a daughter. I only knew that she seemed to enjoy my company as much as I enjoyed hers.

My work with the

Psilocybes

continued into the fall of 1980, but I was having trouble keeping my interest up. I had begun to doubt whether fulfillment lay in the direction of fungal genetics and enzymology. One day in mid-October, Neil called me into his office. “I’ve got a little extra money in the grant this year,” he said, “would you be interested in going to Peru?”

He handed me a flyer from an outfit called the Institute of Ecotechnics. From what I gathered, the institute owned a research vessel, the RV

Heraclitus

, and they were soliciting scientists to join their Amazon expedition the following spring. For a relatively modest cost, they would provide a berth on the boat, meals, and access to some of the remotest collection areas in the Peruvian Amazon. It sounded too good to be true, and as we found out later, it was.

But with my supervisor waving dollars and the chance of an Amazonian adventure in front of me, how could I turn him down? For one thing, I immediately recognized it as a chance to redeem myself: I wanted to prove that I could return to the Amazon and do real science this time—and not go crazy. January 1981 would be the tenth anniversary of my first and only trip to the Amazon, the journey that took us to La Chorrera and beyond. This was an opportunity I couldn’t pass up.

So I dropped my psilocybin thesis project and rewrote my entire program. Instead of working on the enzymes and genetics of

Psilocybe

, I would direct my efforts toward a comparative investigation of the botany, ethnobotany, chemistry, and pharmacology of two important Amazonian hallucinogens: ayahuasca, and

oo-koo-hé

, the orally active preparation made from

Virola

species that had first lured us to La Chorrera. It was an interesting project. Both substances were orally active hallucinogens with DMT as the apparent active compound. In the case of ayahuasca, the monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibiting beta-carboline alkaloids in the stems and bark of a liana,

Banisteriopsis caapi

, apparently allowed the DMT in the leaves of the admixture plants to be orally activated. In theory, the MAO inhibitors in the brew blocked the gut enzymes that normally degraded DMT. As a result, the DMT entered the circulation unchanged and from there readily crossed the blood-brain barrier. The hypothesis seemed reasonable, but no one had actually proven it.

Oo-koo-hé

was even more poorly understood. The substance involved no admixture plants, or none that were known. The sap of various

Virola

species that were high in DMT, 5-MeO-DMT, and related compounds was cooked down to a thick paste, mixed with ashes, and ingested in the form of little pastilles or pills.

All this posed a fascinating riddle. Here were two Amazonian hallucinogens derived from entirely separate botanical sources, both ingested orally, both having tryptamines—namely, DMT—as their active hallucinogenic components. In the case of ayahuasca, the mechanism seemed to involve the blockade of MAO by the beta-carbolines. But for

oo-koo-hé

, the mode of action was much less clear: the active hallucinogens were tryptamines, but did the

Virola

sap also contain its own MAO blockers? It seemed like a reasonable explanation—in fact, I knew that tryptamines and beta-carbolines were closely related compounds that occasionally were found in the same plants. But no one had yet determined if

Virola

sap contained beta-carbolines or not.

The two hallucinogens occupied different ethnographic niches, as well. Ayahuasca was used in the Amazon by many indigenous groups, and had been adopted into mestizo folk medicine. Many admixture plants were associated with it, and there were almost as many different blends as there were individual

ayahuasqueros

. In contrast,

oo-koo-hé

had a highly restricted cultural distribution. It appeared to be used only among the Witoto and the closely related Bora and Muinane tribes. The alkaloid chemistry of some

Virola

species had been studied to a certain degree, but

oo-koo-hé

itself had not been. If the paste contained admixture plants, they were unknown.

It seemed like the ideal thesis project, just waiting for me to get my arms around it. My first objective was to collect as many samples of each preparation as possible, along with specimens of their plant ingredients. From an ethnomedical perspective, I wanted to document how the substances were prepared and applied. Back in the lab, I’d develop methods for determining if those constituents contained tryptamines and beta-carbolines and, if so, how much. Finally, I’d devise assays to measure MAO inhibition and then evaluate sample extracts for this activity.

With my course now redirected, I pursued my work with renewed enthusiasm. Meanwhile, as winter neared, my relationship with Sheila deepened. We were spending a lot of time together, and I was definitely smitten. I discovered she was an excellent cook with a special flair for Indonesian food and a gift for accomplishing culinary marvels on a single hotplate. Even better! It’s sometimes said that the way to a man’s heart is through his stomach, and in Sheila’s case there was some truth to that. Without quite realizing it, I was falling in love again.

Chapter 41 - An Encounter with Ayahuasca

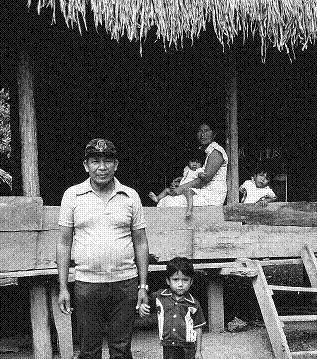

Don Fidel Mosombite, the

ayahuasquero,

and his family.

I continue to be astonished by how readily the mind confabulates, creating its own story to fill in the holes in memory, to the point where I can imagine looking back at the end of life and wondering if any of it really happened. This point was driven home recently when I ran across a daily journal I’d kept on my expedition to Peru. My prolific notes now provide me with a record of many events I’d largely forgotten. This is a blessing, of course, but also a curse, in that it poses an obligation to reconcile what I remember with what I wrote at the time.

Among the recovered details are those that suggest my state of mind in late 1980 as my departure neared. I had mixed feelings about leaving Vancouver for six months, because, having just turned thirty, I realized I’d found in Sheila the love I had been longing for. Even as I was admitting that to myself, I had a strong sense that a major epoch in my life had ended, and that a better chapter was about to begin. That explained my reluctance to leave her for so long. But once again the siren call of the quest was strong. My destiny seemed to be taking me back to the Amazon.

I’d be traveling to Peru with a fellow graduate student named Don, a soft-spoken guy from Victoria, British Columbia. Don intended to focus his collecting on the Euphorbiaceae family, which is notorious for its many toxic members. The plants often contain what are called “phorbol esters,” after the family name, a class of diterpenes that are known to affect cellular processes in many ways; some are considered carcinogens, co-carcinogens, and protein kinase inhibitors. Phorbol esters were important tools for investigating such processes, and newly found ones were always valued. While a few “euphorbs” were used in Amazonian ethnomedicine, a far greater number were recognized as simply toxic. Don’s project was to collect specimens of ethnomedical interest, characterize their chemistry, and devise methods to investigate their activity and mechanisms of action.

While Don and I had been getting ready to depart, Terence and Kat, then living in northern California, had been awaiting the arrival of their second child, Klea, born in December 1980. I was pleasantly surprised when Terence told me he was hoping to join us at some point during the six months we planned to be in Peru. I wasn’t sure how practical his decision was, but he was clearly determined to go.

Don and I left Vancouver in mid-January and drove to California, where I left my car with Terence and Kat. We then took a bus to the Los Angeles area, staying briefly with a professor friend of Neil’s. We were there just along enough to watch the televised spectacle of Ronald Reagan’s first inauguration and the simultaneous release of the Iranian hostages after 15 months of captivity in the American embassy in Tehran. The next day, January 21, we caught our flight to Lima.