The Buried Pyramid (30 page)

And should I defile the good king’s rest?

Neville thought. Then he shook himself violently.

To be turned away by this would mean I believe these tales of heathen gods, and wouldn’t that be blasphemy? There is one God only. Isn’t that the first commandment?

He felt unsettled, and that made him even angrier.

Are you so afraid of a pack of Bedouin wearing fancy dress that you’ll turn back?

he thought.

No!

Trying to keep his qualms to himself, Neville turned the blandest face he could to the others.

“So,” he said. “Are we still on?”

Stephen grinned. “What an amazing discovery this would be! Legends surviving from the time of the ancient Egyptians. Why, if I can reliably document any of this, my contribution will be rated right up there with Champollion’s revelation that Coptic is a survival of the original Egyptian language!”

Eddie was more grim.

“I’m with you. Miriam and I already went through it. I don’t want to back down. What if these Sons of the Hawk decide they want my sons? I won’t have it.”

Jenny said hesitantly, “Uncle Neville, let me go with you. It’s going to be dangerous, and none of you are doctors. You know how well I can stitch a wound. If these Sons of the Hawk try again, you’ll need me.”

Neville shook his head. “No. I’m not bringing a woman into danger.”

Jenny sighed and changed the subject, “Well, after everything Miriam has told us, our story is going to be a bit dull; but don’t you think we should tell Eddie about the Sphinx?”

They did so, producing the various missives as evidence, the final, still encoded one, last of all. Miriam lifted it and studied it curiously.

“You say it was dropped by one of the jackal-headed men last night?”

“Emily said the porter found it on the ground,” Stephen said. “It must have been dropped by one of them.”

“Odd,” Miriam said. “The Bedouin are not highly literate. Still, my brothers learned to read and write Arabic before they left my father. One of them could have learned English in the intervening years. But why would they warn you so strangely?”

“And this grinning woman,” Eddie said. “Could the writer mean Isis? Seems rather disrespectful, given she has nicer titles.”

“Maybe the new letter will clear some of this up,” Jenny said, “now that we know more about the situation.”

“I need to take Miriam home,” Eddie said, “and make certain there has been no further trouble. After my mother-in-law told us what she knew, we realized that we could get some help from the nephews who are living with us. They’re kin on Miriam’s father’s side, and would dread a blood feud with the Bedouin. They’ll keep their mouths shut.”

“And the body?” Neville asked.

“Croc food,” Eddie replied shortly.

After Eddie and Miriam had left, lunch was served. Most of the household retired for the afternoon rest, but Neville was amused to find his young associates unwilling to retire with the cipher unsolved.

“Let’s look at it, then,” he said. “My wound aches enough that I doubt I’ll sleep.”

Jenny rose without comment, got some ice from the kitchen, and very efficiently cleaned and packed the injury. She said nothing further about his refusal to take her along, but Neville felt her every motion as a rebuke.

Jenny was determined not to lose her temper, but it wasn’t easy. She felt that her cool, controlled response to the previous night’s attack deserved acknowledgment. She didn’t like the way Uncle Neville persisted in treating her as though she were the kind of woman who fainted at the sight of blood.

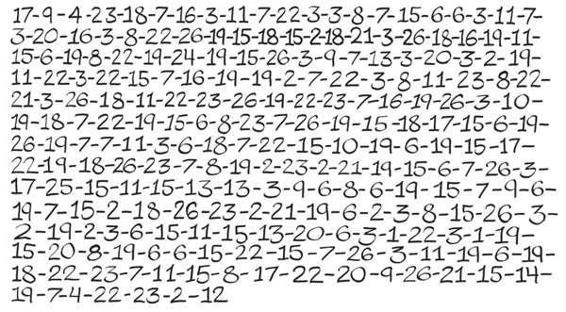

Stephen seemed unaware of the silent conflict raging between uncle and niece—or if he knew of it, he was too smart to comment. He finished writing out the lines of numbers while Jenny tended Sir Neville’s wound, then held out the recopied letter for them both to inspect.

“Whew!” Jenny said, staring at it. “No word breaks, no punctuation. No anything.”

“I notice,” Neville said, “that none of the numbers is higher than twenty-six. That seems to indicate that there is one number for each letter of the alphabet.”

“The last six letters are 7-4-22-23-2-12,” Stephen protested, working something out with pen and paper. “If that is our correspondent’s signature, as has always been the case before, then ‘SPHINX’ should work out to something like 19-16-8-9-14-24.”

“Still,” Jenny said, “Uncle Neville has to be right. It can’t be just coincidence.”

They all stared at the sheet of paper for a long moment. Stephen’s pen scratched as he tried the alphabet against the cipher.

“Q-I-D-W-R . . .” he muttered. “That can’t be right.”

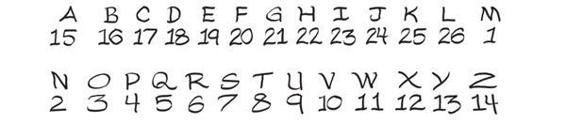

“I’ve got it!” Jenny said excitedly. “You’re working it out as if ‘A’ corresponds to 1, and ‘B’ to 2, and so on, but what Sphinx has done is start in the middle of the alphabet. ‘M’ is 1 and the rest seems to follow directly in order.”

“How do you figure that, Jenny?” Neville asked.

She pointed to the line of numbers.

“See here how in Stephen’s first attempt to work out Sphinx in numbers ‘H’ and ‘I’ become 8 and 9? Well, in this letter we have the fourth and fifth numbers in that last sequence of six falling in that order, too. If we make 22 stand for ‘H’ and 23 stand for ‘I,’ they fall in sequence just as they do in the alphabet.”

She took the pen Stephen extended to her and wrote the entire alphabet in a line. Over ‘H’ she wrote 22, and over ‘I’ 23. Then she wrote rapidly until she reached the end of the alphabet.

“Then we just start with 1 over ‘M’ and continue until we have wrapped around to ‘H’ again,” she said, doing so. “Gentlemen, your key.”

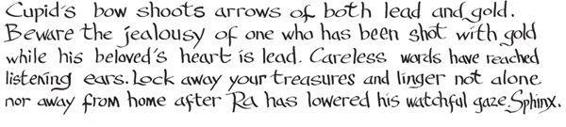

With the key in front of them, it was a matter of minutes to decipher the newest message. Breaking the letters into words wasn’t as easy as it might seem, for what Stephen termed “phantom words” kept jumping out to distract the eye. The phrase “words have reached” became for a moment “word shaver each.” Common sense and patience split the letters into words, then the words into likely sentences. Unhappily for their hopes of revelation, the completed message only added to their confusion.

“What,” Neville asked, “does this about Cupid have to do with murderous tattooed Arabs wearing jackal masks? Certainly they’re not concerned with Eddie Bryce’s courtship of Miriam after all this time!”

“I can’t figure it out either,” Stephen said. “There was something about arrows of lead and gold in Roman mythology as I recall, but up until now we’ve been being warned away from the ‘good king’ and he’s Egyptian. Is this even from our Sphinx?”

Jenny felt a flash of exasperation.

“Of course it is, Stephen. He—or she—uses his name, and the assumption we’d know it, as the key to the entire cipher. Without that, we could have solved it, probably by frequency patterns like in one of those Poe stories Stephen loves so much, but we’d have been longer about it.”

“What I can’t figure out,” Stephen said, “is why the Sphinx would go to all the trouble of creating ciphers, then make it so easy for us to solve them. It took longer to recopy this one than to solve it.”

Jenny wanted to shake him.

“Does that mean then that you’ve figured out what this message is about?” she asked a trace sharply.

The young linguist blinked at her, then colored from his high-buttoned collar to his blond hairline.

“Uh. No idea.”

Jenny didn’t believe him, but she also knew why Stephen Holmboe, linguist, wouldn’t say anything. It looked as if speaking like a Christian would be her job, and given how she was feeling toward her uncle right now, she wasn’t even unhappy about the possibility of embarrassing him.

“Well, I have a pretty good idea,” she said. “Surely you gentlemen must have noticed that Captain Brentworth does not care to have anyone pay attention to Lady Cheshire but himself.”

Uncle Neville replied with what Jenny knew must be feigned nonchalance. “I have, but the lady in question does not seem to care for him a whit.”

“Exactly,” Jenny said. “Captain Brentworth has been shot with the arrow of gold—the arrow that inspires love—while Lady Cheshire has been shot with lead and feels nothing but indifference.”

And I’d swear she is indifferent to you as well, Uncle Neville,

she thought.

But she has her reasons for making sure you think otherwise.

Uncle Neville gave his niece a hard look, and Jenny wondered if she’d spoken aloud.

“Now,” Jenny continued, “apparently our Sphinx thinks that Captain Brentworth feels threatened by one of our number—one of you two gentlemen.”

“And how do you know it is not the reverse?” Uncle Neville said sneeringly. “How do you know that perhaps Lady Cheshire is not threatened by your youth and beauty?”

Jenny flushed. For a moment they ceased to be uncle and niece. She was simply a young woman who had been belittled by an older man.

“For one thing,” she said, pointing with her index finger, “the message expressly says ‘his beloved.’ For another, the only member of our group who has been indulging in flirtation is you.”

Neville Hawthorne colored, but Jenny knew the difference between embarrassment’s blush and anger’s flush. This was anger. She didn’t care.

“Stephen’s only beloved is his books,” she said. “You, however, continue to melt at Lady Cheshire’s least smile. I thought you might even take her up on her offer to accompany you on your expedition—this despite the fact that since before we left England we have been warned against a ‘grinning woman’ and bright smiles.”

Jenny thought she might have gone too far. Uncle Neville was a gentleman of the old school, son of parents whose narrow-mindedness had forced their daughter to elope with her beloved. Neville had been kind to his niece thus far, but Jenny was uncomfortably aware that modern English law now considered women little better than chattel. If he chose, Uncle Neville could do whatever he liked with her.