The Calendar (39 page)

During the months between the vote and enactment the government acquired an unlikely ally in the Church of England, which had finally lined up in favour of reform and adopted a slogan: ‘The New Style the True Style.’ This became the motto of preachers across Britain, who added an appeal to patriotism by repeating John Dee’s assertion that Roger Bacon, an Englishman, was among the first to call for reform some five hundred years earlier.

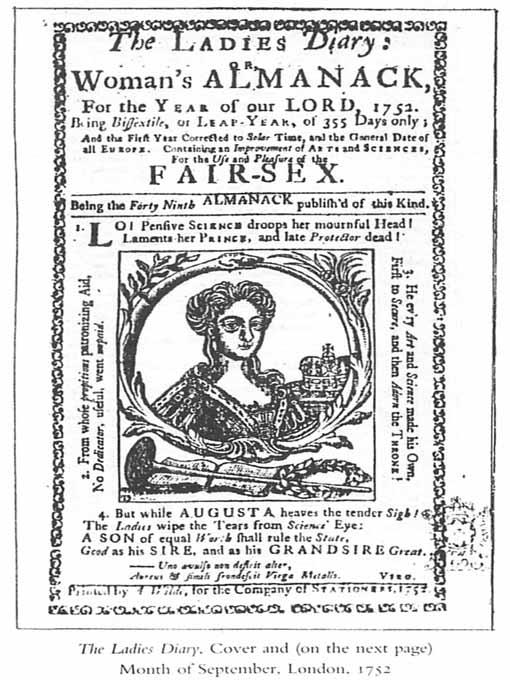

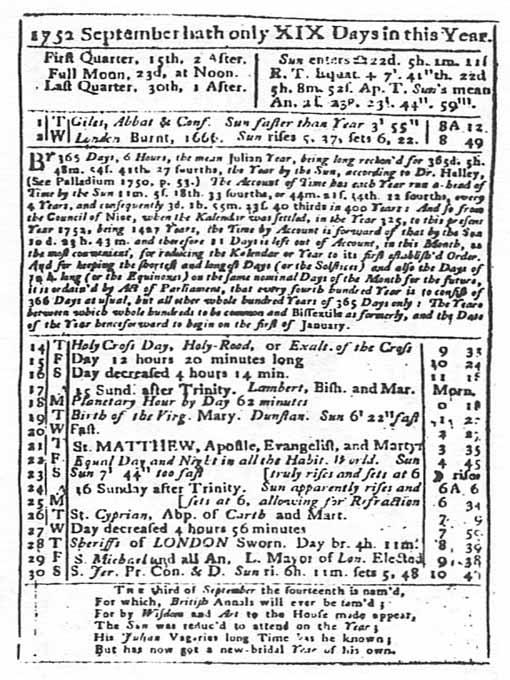

The act was also disseminated in the

London Gazette

and in other newspapers and almanacs. For instance,

The Ladies Diary, or Woman’s Almanack,

published in London, offered a detailed explanation of the change on their cover and in their calendar for the month of September.

Still, many people in Britain reacted with dismay when September actually rolled around--and, in some cases, with anger at the confusion over 11 days lost. William Coxe, editor of Pelham’s memoirs, summarized the response:

In practice . . . this innovation was strongly opposed, even among the higher classes of society. Many landholders, tenants and merchants, were apprehensive of difficulties, in regard to rents, leases, bills of exchange and debts, dependent on periods fixed by the Old Style . . . Greater difficulty was, however, found in appeasing the clamour of the people against the supposed profaneness, of changing the saints’ days in the Calendar, and altering the time of all the immoveable feasts.

In London and elsewhere mobs collected in the streets and shouted, ‘Give us back our eleven days.’ This became a campaign slogan in 1754 in Oxfordshire, where the son of George Parker, the astronomer who made the speech that ignited Stanhope, was standing for Parliament. This election was depicted in a famous set of etchings by William Hogarth (1697-1764). In one of the etchings a banquet is being held by two Whig candidates--one of them is ‘Sir Commodity Taxem’--for their supporters--everyone is revelling, with numerous small scenes showing people eating, a doctor tending to an injured man, musicians playing and a man being struck in the head by a brick tossed by parading Tories. Lying on the floor at the feet of the wounded man is a poster: GIVE US BACK OUR ELEVEN DAYS.

Other protesters shouted out a popular anti-reform ditty:

In seventeen hundred and fifty-three

The style it was changed to Popery.

In Bristol, riots over the reform apparently ended up with people killed. On 6 January 1753, which would have been the day after Christmas Day under the Old Style, a period journal reports:

Yesterday being Old Christmas Day, the same was obstinately observed by our country people in general, so that (being market day according to the order of our magistrates) there were but a few at market, who embraced the opportunity of raising their butter to 9d. or 10d. per pound.

Also in Bristol a certain John Latimer reports that the Glastonbury thorn, which blossomed every year exactly on Christmas Day, ‘contemptuously ignored the new style’ when it ‘burst into blossom on the 5th January, thus indicating that Old Christmas Day should alone be observed, in spite of an irreligious legislature’.

In the City of London, bankers protested the reform and the confusion it caused for their industry by refusing to pay taxes on the usual date of 25 March 1753. They paid up 11 days later, on 5 April, which remains tax day in Britain.

In a lighter vein, a correspondent wrote a letter to

The Inspector

that was published in the September 1752 issue of the popular

Gentleman’s Magazine:

Mr Inspector,

I write to you in the greatest perplexity, I desire you’ll find some way of setting my affair to rights; or I believe I shall run mad, and break my heart into the bargain. How is all this? I desire to know plainly and truly!

I went to bed last night, it was Wednesday Sept. 2, and the first thing I cast my eye upon this morning at the top of your paper, was Thursday, Sept. 14. I did not go to bed till between one and two: Have I slept away days in 7 hours, or how is it? For my part I don’t find I’m any more refresh’d than after a common night’s sleep.

They tell me there’s an act of parliament for this. With due reverence be it spoken, I have always thought there were very few things a British parliament could not do, but if I had been ask’d, I should have guess’d the annihilation of time was one of them!

Most people, however, did not seem too rattled by the change, with most diarists at the time simply mentioning the event with little comment. James Clegg, a 62-year-old minister and farmer living in Derbyshire, jotted down what he considered key events in his life for September 1752:

1. heavy rain all the forenoon, I was back home close at work writing my last will and was at home all day.

2. at home til afternoon then took a ride out into Chinley, visited at old William Bennets and at John Moults at Nase and returnd safe Blessed be God.

14. This day the use of the new Stile in numbring the days of the months commenceth and according to that computation, the last day of October will be my Birthday. I was at home til afternoon, we had an heavy shower of rain which raizd the water, after it was over I went up to Chappel on business and returned home in good time.

Newspapers also noted the change, but little more. None reported on the riots or other problems, since this was not yet part of what constituted a duty or practice of the general press. The

General Advertiser

of London printed excerpts from the act in its 2 September 1752 (Old Style) edition. The next day, 14 September was marked in the paper with a simple N.S. after the date. Otherwise the paper ran its usual mix of news from world capitals, shipping notices, stock quotes and advertisements. The latter included on this first day of the new calendar an announcement that ‘The Evening Entertainments’ at Spring Gardens, Vauxhall, ‘will end this evening, the 14th of September, N.S.’ There also was to be a violin concert that night at Islington, a sale of ten barges at Billingsgate at noon the following Tuesday, and a meeting of the governors of the Small-Pox Hospital on 20th September. High water at London Bridge was at 5:28 PM.

Across the Atlantic in the British colonies, Benjamin Franklin’s

Poor Richard’s Almanac,

published in Quaker Philadelphia, noted:

At the Yearly Meeting of the People called Quakers . . . since the Passing of this Act, it was agreed to recommend to the Friends a Conformity thereto, both in omitting the eleven Days of September . . . and beginning the Year hereafter on the first Day of the Month called January.

The author of this notice, R. Saunders, then extended a wish to his readers ‘that this New Year (which is indeed a New Year, such an one as we never saw before, and shall never see again) may be a happy Year’.

In this same almanac Franklin himself, then 46, jauntily told his readers:

Be not astonished, nor look with scorn, dear reader, at such a deduction of days, nor regret as for the loss of so much time, but take this for your consolation, that your expenses will appear lighter and your mind be more at ease. And what an indulgence is here, for those who love their pillow to lie down in peace on the second of this month and not perhaps awake till the morning of the fourteenth.

A number of colonial newspapers--including The Boston Weekly News-Letter, The Carolina Gazette, and The New York Evening Post --noted the arrival of the New Style but say little more.

Britain was not the last country to change in Europe. Sweden changed the next year, in 1753. Then there is a long gap, with the heavily Greek Orthodox countries in the Balkans waiting until the early twentieth century. Bulgaria made the switch in either 1912, 1915 or March of 1916, depending on which source one believes. Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia converted around 1915, during the German occupation; Romania and Yugoslavia made the change in 1919. Russia waited until 1918, after the Bolshevik Revolution, but had to drop 13 days--February 1-13--to make up for the accumulation of days by which the Julian calendar was in error 336 years after the Gregorian reform. Greece did not reform its civil calendar until 1924.

Countries and people outside of Europe mostly had no reaction to the new calendar in the decades and centuries following 1582--the exception being in the Americas, where the reform was imposed by Spain and Portugal on those people they had conquered. These included the Aztecs, Incas and Mayas, whose brilliant work in astronomy and calendars was already mostly forgotten and expunged by the Europeans, though to this day isolated groups of Maya, for one, continue to use their ancient calendar. Later, Britain, France, the United States and other colonial powers imposed their calendar on Indian tribes in the Western Hemisphere.

In Asia, the Japanese adopted the Gregorian calendar in 1873, during the Westernization period of the Meiji emperors. Most countries and peoples on this continent and in Africa preferred to keep their own calendars unless forced to change by European colonial powers. Many continue to use traditional calendars for religious and cultural events.

China resisted until 1912, though the Gregorian calendar did not take hold throughout that country until the victory of the Communists in 1949. On 1 October of that year a triumphant Mao Zedong climbed up onto a stand atop the Gate of Heavenly Peace, the main entrance to the imperial palace in Beijing. He then ordered that Beijing be henceforth the capital of China, that the red flag with a large gold star and four small stars be the official flag of China, and that the year be in accord with the Gregorian calendar.

But by then this calendar, launched 2000 years earlier by Julius Caesar and modified 1600 years later by a lacklustre pope, had become the world’s calendar: a code for measuring time that today all but the most isolated peoples use as the global standard for measuring time. This is despite its odd quirks and the twists of history that produced it, following an improbable timeline of its own from Sumer and Babylon to Rome, from Gupta India and the Islamic east to a gradually reawakening Europe, the Renaissance, Lord Chesterfield’s England and beyond.

Today the quest continues in the age of atomic time--which takes us, at last, to Building 78 at the US Naval Observatory in Washington, DC, where time is now measured not by watching the moon and sun, or with a sundial, water clock, pendulum, wound-up spring or quartz crystal, but with a tiny mass of a rare element called caesium.

15 Living on Atomic Time

But time is too large, it refuses to let itself be filled up.

Jean-Paul Sartre

I am standing in front of the master clock.

It resides in a small bunker-like structure, on top of a grassy knoll. Here the output of some 50 individual atomic clocks converge into a bank of computers behind a thick pane of glass at the US Naval Observatory. Smack in the middle of the panels and pulsating lights is a digital read out ticking past in bright red numbers: hours, minutes and seconds. This is literally the pulse of North America in this age of atomic time. It also contributes to a larger system that keeps time for the entire world, accurate within a billionth of a second a year, or 0.0000000000000000315569 of a year.

Except that official time is no longer really measured this way, using antiquated seconds and years. Since 1972, when the atomic net went online, the Co-ordinated Universal Time--UTC--has been measured not by the motion of the earth in space but by the oscillations at the atomic level of a rare, soft, bluishgray metal called

caesium.

Apparently every atom oscillates--something I was unaware of before I visited the Naval Observatory. But before anyone gets alarmed, you should realize that all matter absorbs and emits a certain amount of energy, and that this happens in some elements with extraordinary regularity--absorb, emit, absorb, emit, absorb, emit--a process not unlike the steady swing of a pendulum, and which can be picked up by instruments as a steady frequency.

In 1967 the rate of caesium’s pulse was calibrated to 9,192,631,770 oscillations per second. This is now the official measurement of world time, replacing the old standard based on the earth’s rotation and orbit, which had used as its base number a second equal to 1/ 31556925.9747 of a year. This means that under this new regime of caesium, the year is no longer officially measured as 365.242199 days, but as 290,091,200,500,000,000 oscillations of Cs, give or take an oscillation or two.