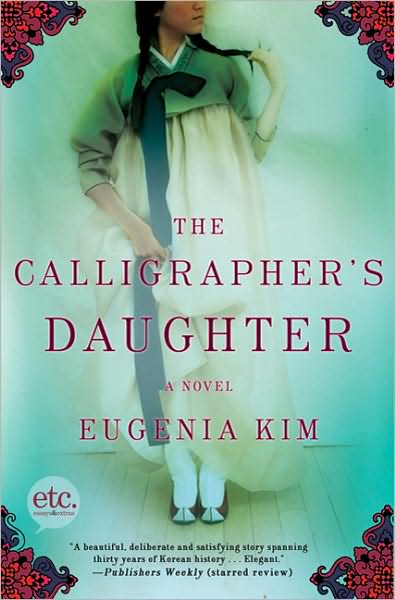

The Calligrapher's Daughter

Henry Holt and Company, LLC

Publishers since 1866

175 Fifth Avenue

New York, New York 10010

[http://www.henryholt.com] www.henryholt.com

Henry Holt® and ® are registered trademarks of Henry Holt and Company, LLC.

® are registered trademarks of Henry Holt and Company, LLC.

Copyright © 2009 by Eugenia Kim

All rights reserved.

The poem “A Dream,” which is quoted on pages 185 and 223, is from

Among the Flowering Reeds: Classic Korean Poems in Chinese

, translated by Kim Jong-Gil, White Pine Press (Whitepine.org), 2003.

Distributed in Canada by H. B. Fenn and Company Ltd.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Kim, Eugenia.

The calligrapher’s daughter : a novel / Eugenia Kim. — 1st ed.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-0-8050-8912-7

ISBN-10: 0-8050-8912-8

1. Korea—Fiction. I. Title.

PS3611.I453C35 2009

813’.6—dc22

Henry Holt books are available for special promotions and premiums.

For details contact: Director, Special Markets.

First Edition 2009

Designed by Meryl Sussman Levavi

Painted illustrations by Alice Hahn Hyegyung Kim

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

I LEARNED I HAD NO NAME ON THE SAME DAY I LEARNED FEAR. UNTIL that day, I had answered to Baby, Daughter or Child, so for the first five years of my life hadn’t known I ought to have a name. Nor did I know that those years had seen more than fifty thousand of my Korean countrymen arrested and hundreds more murdered. My father, frowning as he did when he spoke of the Japanese, said we were merely fodder for a gluttonous assimilation.

The servants called me

Ahsee

, Miss, and outside of the family I was politely referred to as my mother’s daughter. To address an adult by name was considered unspeakably rude. Instead, one was called by one’s family relational position, or profession. My father was the literati-scholar-artist,

the calligrapher Han, much respected, and my mother was the scholar’s wife. And because my mother wasn’t native to Gaeseong, she was also properly called “the woman from Nah-jin,” a wintry town on the far northeast border near Manchuria. Thus, if a church lady said, “That one, the daughter of the woman from Nah-jin,” I knew I was in trouble again.

I wasn’t a perfect daughter. Our estate overflowed with places to crawl, creatures to catch and mysteries to explore, and the clean outside air, whether icy, steamy or sublime, made me restive and itching with curiosity. Mother tried to discipline me, to mold my raw traits into behavior befitting

yangban

, aristocrats. An only child, I was expected to uphold a long tradition of upper-class propriety. There were many rules—all seemingly created to still my feet, busy my hands and quiet my tongue. Only much later did I understand that the sweeping change of those years demanded the stringent practice of our rituals and traditions; to venerate their meaning, yes, but also to preserve their existence simply by practicing them.

I couldn’t consistently abide by the rules, though, and often found myself wandering into the forbidden rooms of my father. Too many fascinating things happened on his side of the house to wait for permission to go there! But punishment had been swift the time Myunghee, my nanny, had caught me eavesdropping outside his sitting room. She’d switched the back of my thighs with a stout branch and shut me in my room. I cried until I was exhausted from crying, and my mother came and put cool hands on my messy cheeks and cold towels on my burning legs. I now know that she’d sat in the next room listening to me cry, as she worked a hand spindle, ruining the thread with her tears. Many years later, my mother told me that the cruelty of that whipping had revealed Myunghee’s true character, and she wished she had dismissed her then, given all that came to pass later.

I didn’t often cry that dramatically. Even at the age of five, I worked especially hard to be stoic when Myunghee pinched my inner arms where the bruises wouldn’t be easily discovered. It was as if we were in constant battle over some unnamed thing, and the only ammunition I had was to pretend that the hurts she inflicted didn’t matter. Hired when I was born, Myunghee was supposed to be both nanny and companion. Her round face had skin as pale and smooth as rice flour, her eyes were languid with

what was mistaken for calm, and her narrow mouth was as sharp as the words it uttered. When we were apart from the other servants or out of sight of my mother, Myunghee shooed me away, telling me to find my own amusement. So I spied on her as she meandered through our house. She studied her moon face reflected in shiny spoons, counted silver chopsticks, fondled porcelain bowls and caressed fine fabrics taken from linen chests. At first I thought she was cleaning, but my mother and I cleaned and dusted with Kira, the water girl. Perhaps she meant to launder the linens, but Kira did the laundry and was also teaching me how to wash clothes. Maybe the bowls needed polishing, but Cook was very clear about her responsibilities and would never have asked for help. As I spied on Myunghee, I wondered about her strangeness and resented that she refused to play with me.

My mother’s visit had brought me great relief, but my stinging thighs sparked a long-smoldering defiance and I swore to remain alert for the chance to visit my father’s side of the house again.

And so on this day, when six elders and their wives came to visit, I found my chance after the guests had settled in—the women in Mother’s sitting room and the men with Father. I crept down Father’s hallway, nearing the big folding screen displayed outside his door, and heard murmurings about resisting the Japanese. The folding screen’s panels were wide enough for me to slide into a triangle behind an accordion bend. The dark hiding place cooled the guilty disobedience that was making me hot and sweaty, a completely unacceptable state for a proper young lady. I breathed deeply of the dust and dark to calm myself, and cradled my body, trying to squeeze it smaller. Pipe smoke filtered through the door, papers shuffled, and I wondered which voice in the men’s dialogue belonged to whom. The papers must have been my father’s collection of the

Daehan Maeil News

I knew he’d saved over the past several months. This sole uncensored newspaper, distributed nationwide for almost a full year, had recently been shut down. The men discussed the forced closure of the newspaper, Japan’s alliance with Germany, its successes in China and unceasing new ordinances that promoted and legalized racial discrimination. Naturally I understood none of this, but the men’s talk was animated, tense and punctuated repeatedly with unfamiliar words.

I slipped from behind the screen, tiptoed down the hall and, once

safely on our side of the house, ran to Mother’s room, eager to ask what some of those words meant:

Europe, war, torture, conscript, dissident

and

bleakfuture.

The men’s wives sat around the open windows and door of my mother’s sitting room, fanning themselves, patting their hair and fussing about the humidity. I spun to retreat, realizing too late that Mother would be in the kitchen supervising refreshments. A woman with painted curved eyebrows and an arrow-sharp chin called

“Yah!”

and beckoned me closer.

“You see?” Her skinny hand pecked the air like an indignantly squawking hen. The others turned to look, and I bowed, embarrassed by their attention, sure that my cheeks were as pink as my skirt. Garden dirt clung to my hem, but I managed to refrain from brushing it off and folded my hands dutifully, keeping every part of me still.

Another woman said, “She’s pretty enough.” I felt their eyes studying me. My hair was braided as usual into two thick plaits that hung below my shoulders. Still plump with childhood, I had gentle cheekbones, round rabbit eyes wide apart, a flat bridge above an agreeable nose, and what I hoped was an intelligent brow, topped with short hairs sprouting from a center part. Unnerved by their stares, involuntarily I grasped a braid and twisted it.

“Still, it’s unusual for such a prominent scholar,” said the arched-eyebrow woman, “don’t you think?”

“Unusual?”

“Well, yes. Granted, she’s a girl,” and she turned her head theatrically to hold every eye in the room, “but isn’t it odd for a man whose lifelong pursuit is art, literature and scholarship—the study of words!—that such a man would neglect naming his own daughter?”

The ladies chimed in with

yah

and

geulsae

and similar sounds of agreement, and the woman waved me away.

I left for the kitchen, frowning, and though I don’t like to admit it, pouting as well. Cook and Kira were helping my mother prepare platters of fancy rice cakes, decoratively sliced plums and cups of cool water. Before reaching the door I heard my mother say, “Where is that Myunghee?” I stopped to eavesdrop, surprised at her obvious irritation. She regularly cautioned me to never speak crossly to or about the

servants. Myunghee was notorious for disappearing when work called, and now had pushed my mother—who hardly ever raised her voice—into impatience. Remembering my tender thighs, I gloated a little.